During his anthropological surveys of Edo- and Igbo-speaking communities in Southern Nigeria between 1909 and 1913, N. W. Thomas collected and recorded a number of examples of local flutes. Thomas gives the Edo name for these as alele, elele or ulele (depending on dialect); he records the Igbo name as ọja. In the first volume of his Anthropological Report on the Ibo-speaking Peoples of Nigeria, Thomas notes that, next to the drum, the flute was probably the commonest musical instrument in the region; he also observes that there are ‘two or three kinds made of wood’, and another kind ‘made of calabash covered with the skin of a cow’ (1913: 136). Thomas distinguishes different styles of flute music, played in different contexts, for example during wrestling matches, during wall-making and while drinking palm wine (ibid.).

Ọja is the most common of the wind instruments. It is made of wood, usually a light soft wood, and of bamboo. The wooden ọja is notched and end blown, while the bamboo ọja, also notched, is side blown. Of the two types of ọja only the wooden one has survived the changing times. The explanation of this survival can once again be found in its deep functionality in Igbo cultural and social life. The characteristic of ọja is the high-pitched sound which the different types produce. This is because this family of instruments is small in size. The biggest ọja discovered by this author is about 26cm long, and the smallest about 14cm long. The size of an ọja determines its pitch and the quality of sound determines the instrument’s function. The highest-pitched flutes, which are also the shortest, are known either as ọja-mmonwu (flutes used for masquerade music) or ọja-okolobia (flutes used for ceremonies of men who have attained manhood). The sound of both flutes is bright and they are used more for chanting than for singing. The difference between the two styles is that chanting is an extended form of speaking, while singing is purely musical.

The lowest-pitched flutes are known as ọja-igede. Igede is a drum music used for burial ceremonies, and ọja-igede is used in pairs with the male ọja calling and the female ọja responding.

The next ọja, whose sound is half way between the highest-pitched and the lowest-pitched ones, is known as ọja-ukwe (the singing flute). This is used for women’s dances of all types.

As an instrument, it is fundamentally employed for performance-composition of melodies, as well as simulation of texts in music and dance performance situations. It provides lyrical melodies that contribute immensely to the overall timbre and aesthetics of Igbo music. In some musical performances oja effectively employed for non-verbal communication with ensemble members as well as the audience. This could be in the form of cues, musical signals or mere encouragement of dancers and players to a more creative performance. … In some instances, oja is employed as a master instrument that conducts and marshals or determines a musical event or performance form. This is found in some masquerade performances such as Ojionu. But, oja performs both musical and non-musical roles in Igbo land. Its use extends beyond the musical. It is employed in non-musical events and contexts as a talking instrument. As such it encodes significant messages within non-musical contexts. In such instances it conveys relevant messages to cognitive members or initiates in a a ceremony. It is, particularly, used for salutations and praise on these occasions.

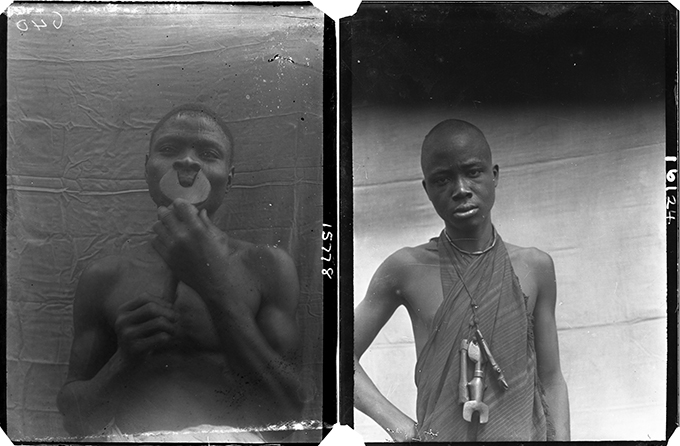

Northcote Thomas made several recordings of flute playing using his wax cylinder phonograph, which illustrate a number of different styles. Beyond stating where and when they were recorded, Thomas unfortunately provided little further information about the different styles. Here are three examples:

‘Uzebba flute, June 10th, 1909’ (NWT 137; BL C51/2424) – this is likely to be a recording of the flute player in the photograph on the left above (NWT 640):

‘Flute record, taken at Awka, December 13th, 1910’ (NWT 409; BL C51/2636):

‘Record 441, taken at Awgulu, February 8th, 1911’ (NWT 441; BL C51/2683):

A number of videos of contemporary ọja players can be found online.

References

- Lo-Bamijoko, J. N. (1987) ‘Classification of Igbo Musical Instruments’, African Music 6(4): 19-41.

- Onyeji, C. U. (2006) ‘Oja (Igbo wooden flute): An Introduction to the Playing Technique and Performance’, in M. Mans (ed.) Centering on African Practice in Musical Arts Education (pp.195-208), Cape Town: African Minds.

- Thomas, N. W. (1913) Anthropological Report on the Ibo-speaking Peoples of Nigeria, Part 1: Law and Custom of the Ibo of the Awka Neighbourhood, London: Harrison & Sons.

This is an invaluable resource for Igbo studies. I will recommend it to my PhD candidate who is researching on Traditional African Flutes.

Many thanks, Ngozi. We’d love to hear more about your student’s work. Perhaps s/he could tell us more about the flutes Northcote Thomas collected and help us understand the flute music he recorded?

Thanks so much for the information… This will help on my termpaper research