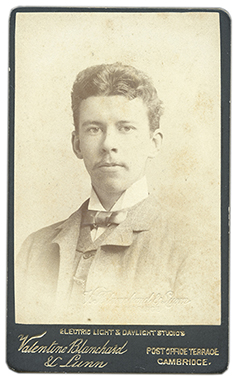

Northcote Whitridge Thomas (1868-1936) was the first official government anthropologist to be appointed by the British Colonial Office. He was born in the English market town of Oswestry, near the Welsh border. Although his mother and father lived until 1907 and 1914 respectively, as a child Thomas was informally adopted by his mother’s elder sister, Katherine Toller, and her husband, John Askew Roberts. Roberts was a successful businessman, who ran the local Oswestry Advertizer newspaper and took a keen interest in archaeology and local folklore, the possible source of Thomas’s interest in folklore studies and ethnology.

Thomas studied History at Trinity College, Cambridge between 1887 and 1891, and was awarded an MA in 1894. The famous anthropologist, folklorist and author of The Golden Bough, J. G. Frazer, was a Fellow of Trinity College. Thomas certainly became an acquaintance of Frazer in later life, though we do not know whether he fell under his influence while studying at Cambridge. By 1894 it was clear that Thomas had decided to pursue folklore and ethnological studies. Since no university in Britain yet taught these subjects, Thomas went to study ‘primitive religion’ at the École pratique des hautes études in Paris under Léon Marillier. Among his near contemporaries were Marcel Mauss and Arnold van Gennep. Thomas’s research interests at this time focused on European folk stories and superstitions relating to animals. Influenced by E. B. Tylor, he speculated that these represented the vestiges of totemism. In 1897 he submitted a thesis entitled ‘La Survivance du culte des animaux au Pays de Galles’ and was awarded a diploma. Between 1897 and 1900 Thomas lived in Kiel, northern Germany, where he continued to study European folklore as well as modern European languages.

Thomas returned to Britain in 1900 and was appointed as Assistant Secretary and Librarian at the Anthropological Institute. The period until his appointment as Government Anthropologist in 1909 was an intensely busy one for Thomas, and saw him become an established figure in anthropological circles. He served on the Councils of the Folklore Society and (Royal) Anthropological Institute, and wrote or edited several books, including volumes of the County Folklore series, Natives of Australia (1906), Kinship Organisation and Group Marriage in Australia (1906), Anthropological Essays presented to Edward Burnett Tylor (1907, with R. R. Marett and W. H. R. Rivers) and Women of All Nations (1908, with T. A. Joyce). Thomas intended to conduct anthropological fieldwork in Australia at this time, but was unable to raise the funds.

Thomas’s interests in West Africa seem to have arisen through his acquaintance with R. E. Dennett, who had been a trader in the Congo before being appointed as Deputy Chief Conservator of Forests in Southern Nigeria. Dennett was also an amateur ethnologist and collector, who published articles in scholarly journals. Thomas edited the manuscript of Dennett’s 1906 book, At the Back of the Black Man’s Mind: Or Notes on the Kingly Office in West Africa. This was a comparative study of Vili and Bini customs and belief. Indicative of his shifting interest towards Africa, Thomas also published an article on ‘The Market in African Law and Custom’ in 1908. Like his book-length studies of Australian kinship and totemism, this was a typical work of ‘armchair anthropology’, with data drawn from a wide variety of sources and not based on his own field research.

The opportunity to conduct anthropological fieldwork of his own would come in 1909, with Thomas’s appointment as Government Anthropologist in Southern Nigeria. But that will be the subject of another post.

Further details about N. W. Thomas’s biography and career can be found in the article ‘N. W. Thomas and colonial anthropology in British West Africa: reappraising a cautionary tale’, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 22: 84-107.