[Re:]Entanglements is collaborating with the Art Assassins, the young people’s forum of the South London Gallery in Peckham. As part of the project, the Art Assassins are working with a number of London-based artists and researchers with connections to West Africa. The idea is for each artist or researcher to use their creative practice to help the Art Assassins explore the Northcote Thomas collections and archives, and consider its relevance for young people in South London today. The Art Assassins’ work will culminate in an exhibition at the South London Gallery, which they will curate themselves.

The first researcher-in-residence to collaborate with the group is Emmanuelle Andrews. Emmanuelle is a researcher and social justice advocate, specialising in the human rights of LGBTI+ people across the Commonwealth, where the criminalisation of same-sex intimacy exists predominantly as a result of colonial-era laws. Domestically, Emmanuelle focuses on racial justice and community resilience, researching issues such as the 2011 London Riots and the Notting Hill Carnival as well as exploring solidarity-making across histories of black radical movements, as in her film Coming to Love.

Since October Emmanuelle has been guiding the Art Assassins through provocative encounters with Northcote Thomas’ work and its legacy. Through discussion and creative exercises she has challenged the group to confront the archive as a method for reflecting on their own entanglements with colonialism. In this guest blog post Emmanuelle looks back on her experience working with the Art Assassins.

Confronting the disciplines

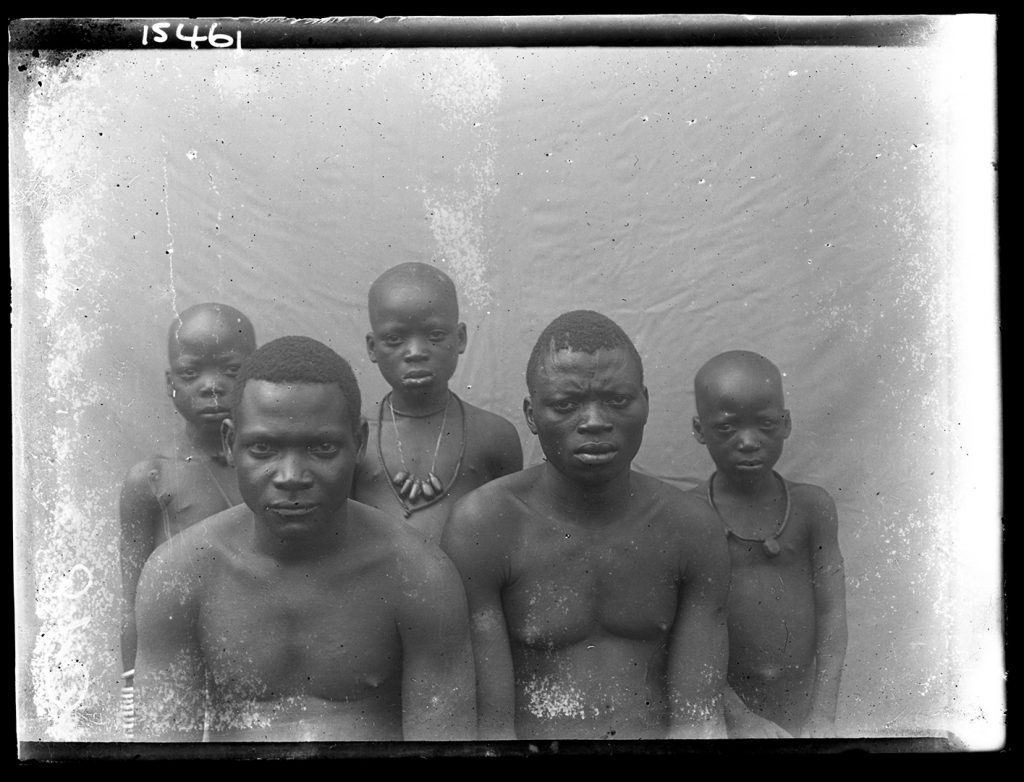

In my first encounter with the Art Assassins I began with sharing a personal reflection on a visit to the Royal Anthropological Institute (RAI) with Paul Basu, leader of the [Re:]Entanglements project and Professor of Anthropology at SOAS University of London. Having studied Anthropology and Law for my undergraduate degree, before studying a Masters in Gender, Race, Sexuality and Social Justice, this experience was a (re)visit to my disciplinary ‘home’: Anthropology. What I wanted to encapsulate to the Art Assassins was the feeling of lacking belonging here and the field of Anthropology as one that invites, for a black women like myself, a visceral combustion of self and other, as I reflected on my position as being a recipient of the colonial anthropological gaze, as well as potentially an instigator of it. Sitting in the RAI, I considered the historical reality that I was never meant to be there in this form – valued (at least originally) as the ‘viewed’ and not the ‘viewer.’ I hoped to bring to the forefront for the Art Assassins the fact that any dabbling in Northcote Thomas’ work will always be personal, as our very beings refract through the colonial archive.

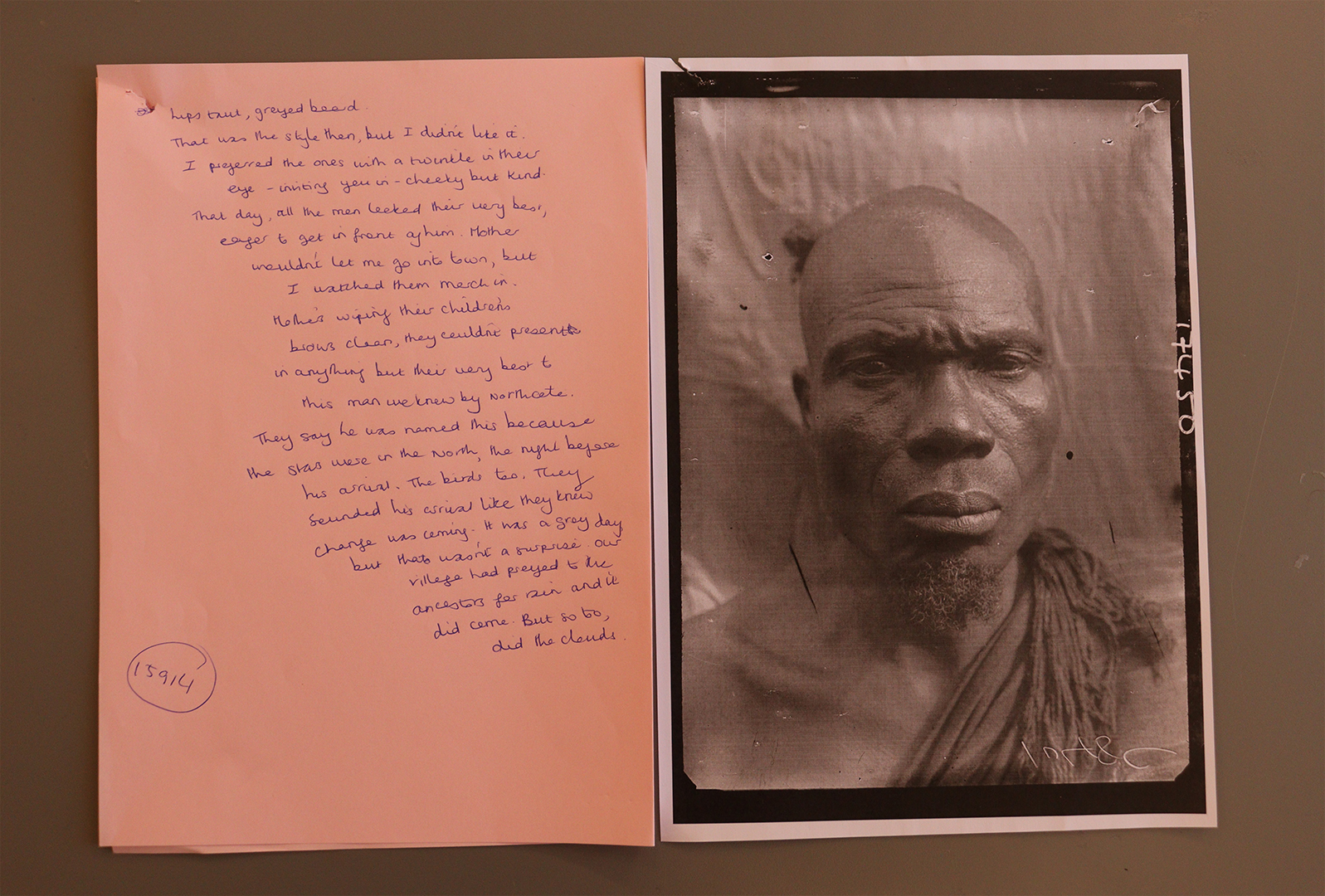

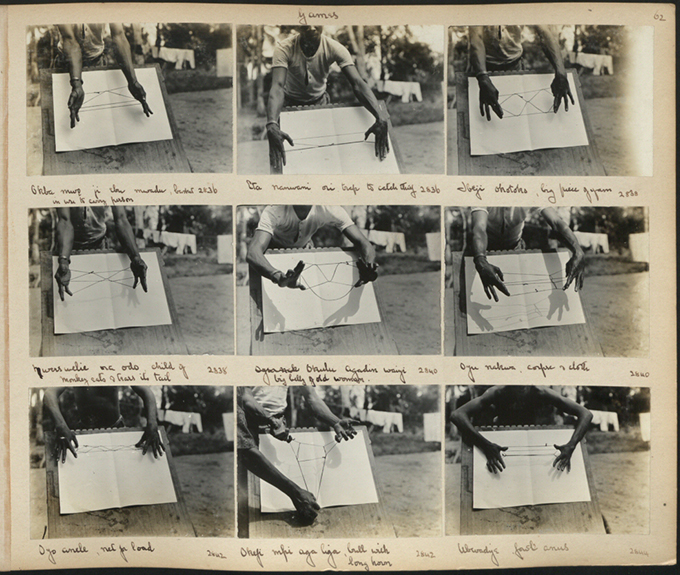

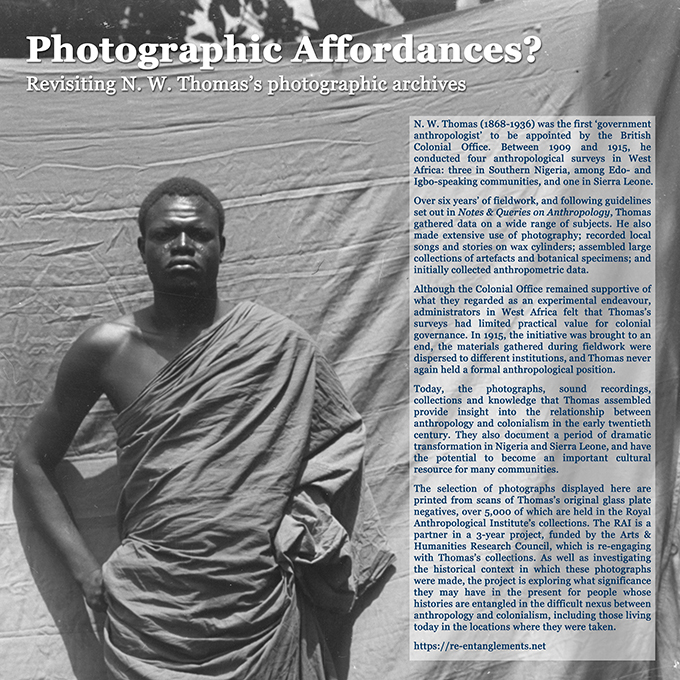

During my visit to the RAI, I also looked at the collection of Thomas’ plate glass negatives, and handled some of his photographic registers, in which he categorised and annotated the images. Afterwards, I joined the Art Assassins at the British Library Sound Archive where we explored its collection of Thomas’s and other historical ethnographic and ethnomusicological wax cylinder recordings. You can read more about our visit here.

Listening to images

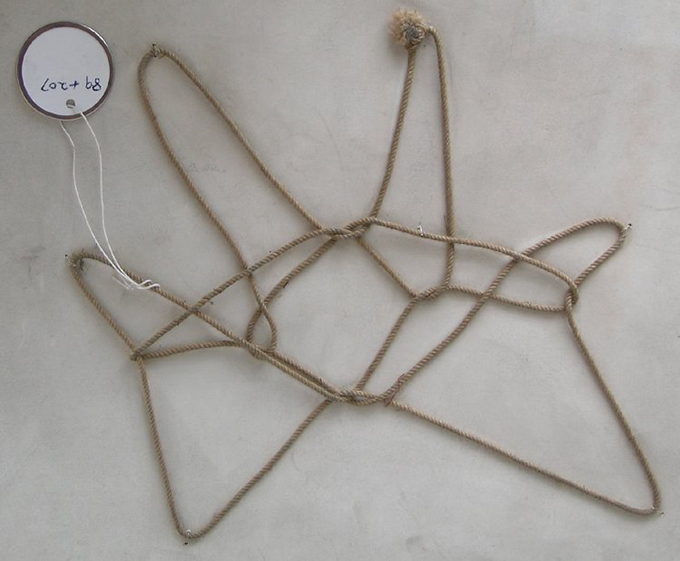

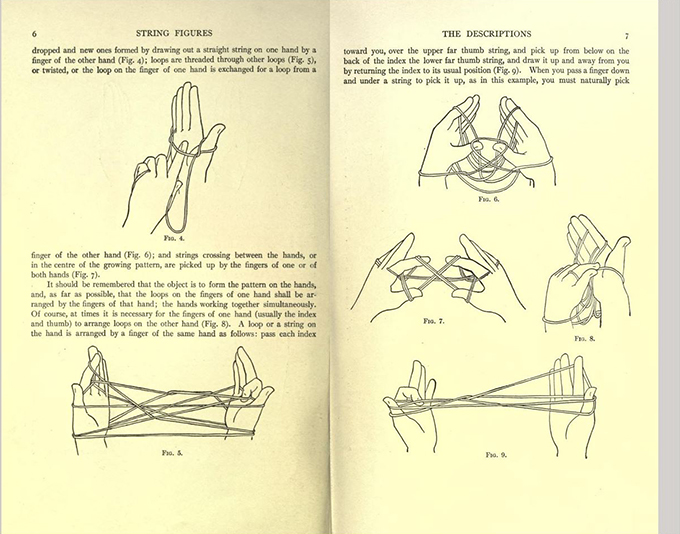

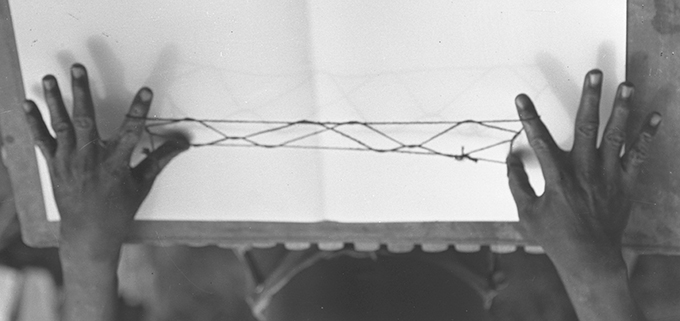

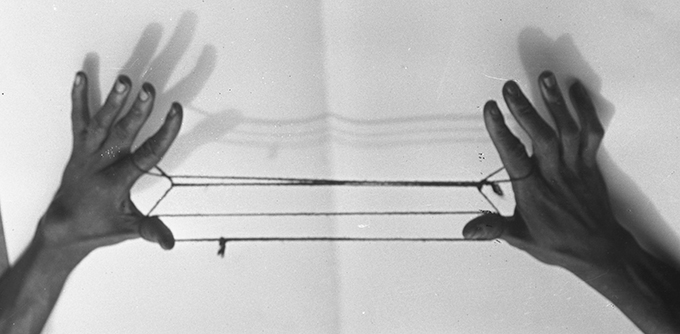

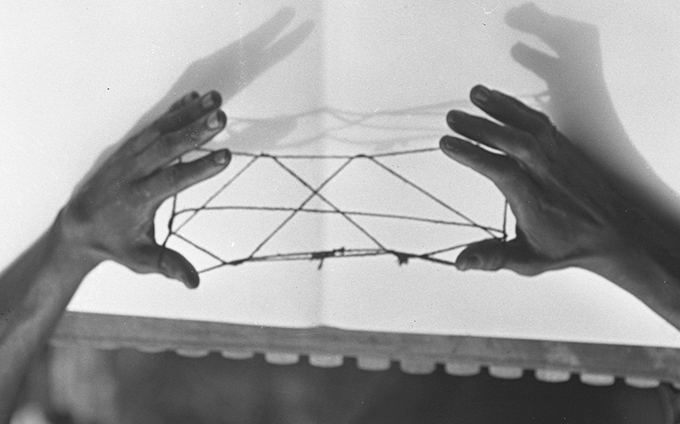

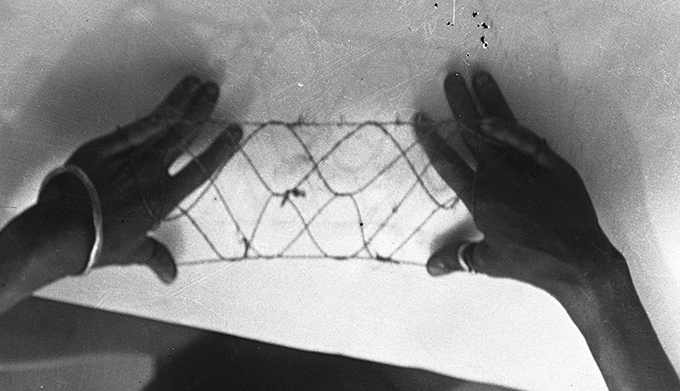

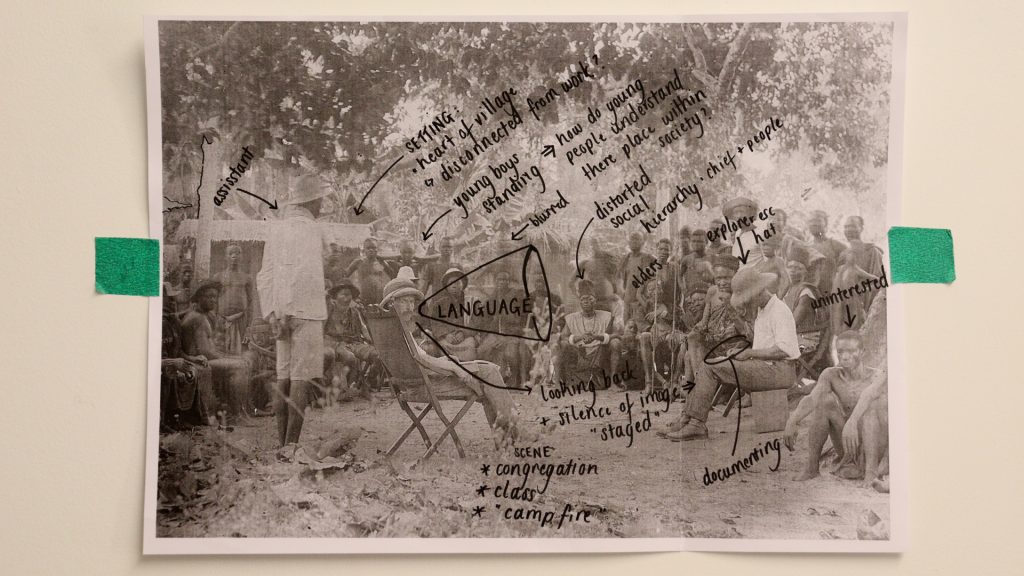

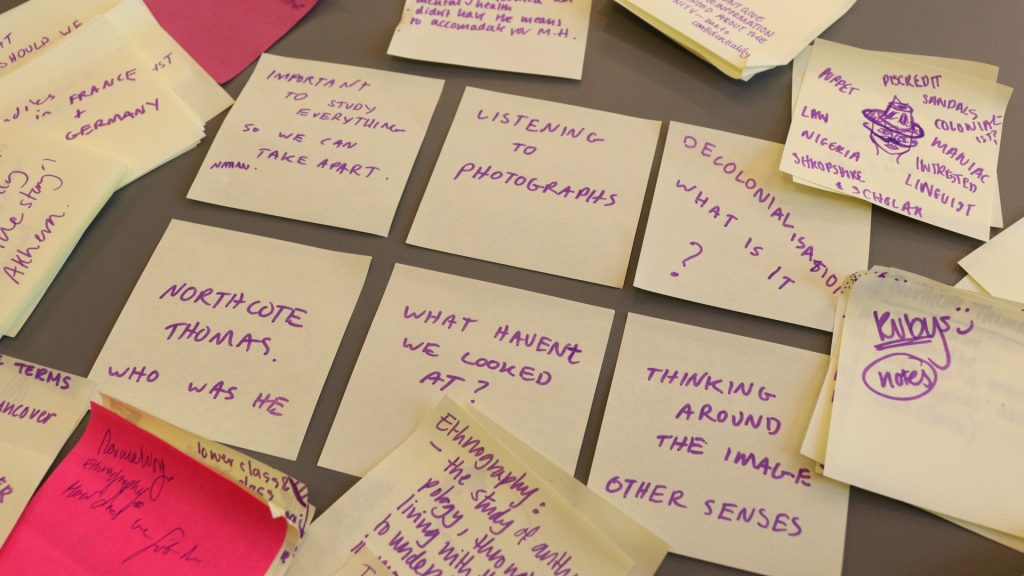

The visit to RAI and the British Library Sound Archive inspired me to begin my first workshop with the Art Assassins at the intersection of sound and image. I invited the group on a journey through the archive by other means: through a privileging of the senses that confront Western ontology’s desires to judge knowledge through the rationale of scientific certainty.

Watching the beautiful and award-winning film, Faces|Voices, produced as part of the [Re:]Entanglements project, and featuring the film’s participants voicing their responses to Northcote Thomas’ photographic archive, I moved the group to consider whether Thomas’s images were necessarily ‘silent’ in the first place. (In what ways are these images silent? For whom? In what languages?)

Drawing the link between Anthropology’s motivation of filling supposed gaps about distant others and the related violence of Western knowledge-making, I used the film as a starting point to complicate questions of who, in the colonial anthropological project, had voice and who were silenced. I wanted to push the Art Assassins away from a simple reading of Northcote Thomas as the powerful agent of colonialism and his subjects as agentless victims. While we cannot, and should not, ignore the colonial context of Northcote Thomas’s anthropological surveys, it became clear that we can achieve this without reproducing its grammars of violence.

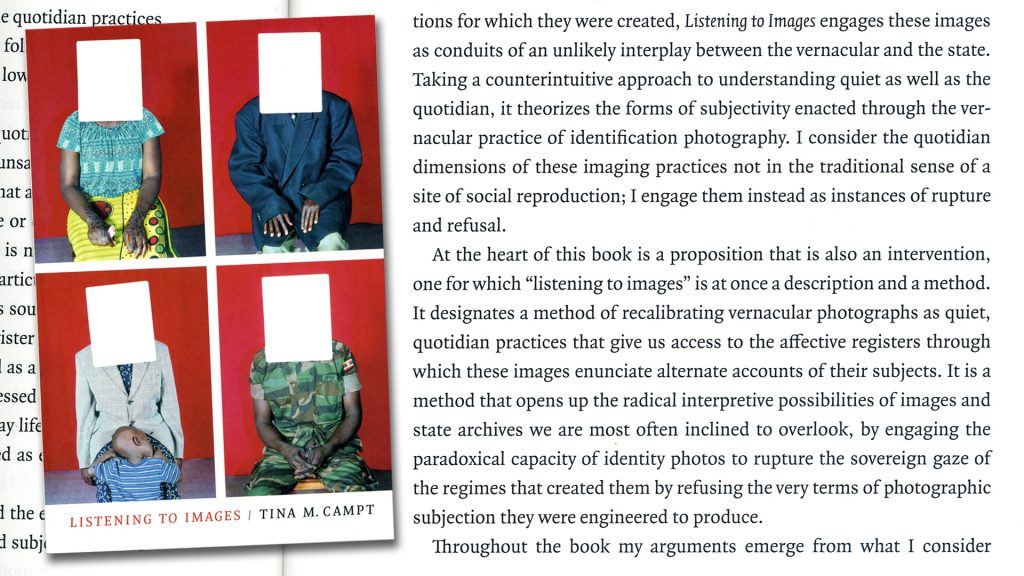

To ground this reading, I introduced the group to Tina M. Campt’s concept of ‘listening to images’, which she describes as both…

a description and a method … [It] opens up the radical interpretive possibilities of images …. To ‘listen to’ rather than simply ‘look at’ images is a conscious decision to challenge the equation of vision with knowledge by engaging photography through a sensory register that is critical to Black Atlantic cultural formations: sound.

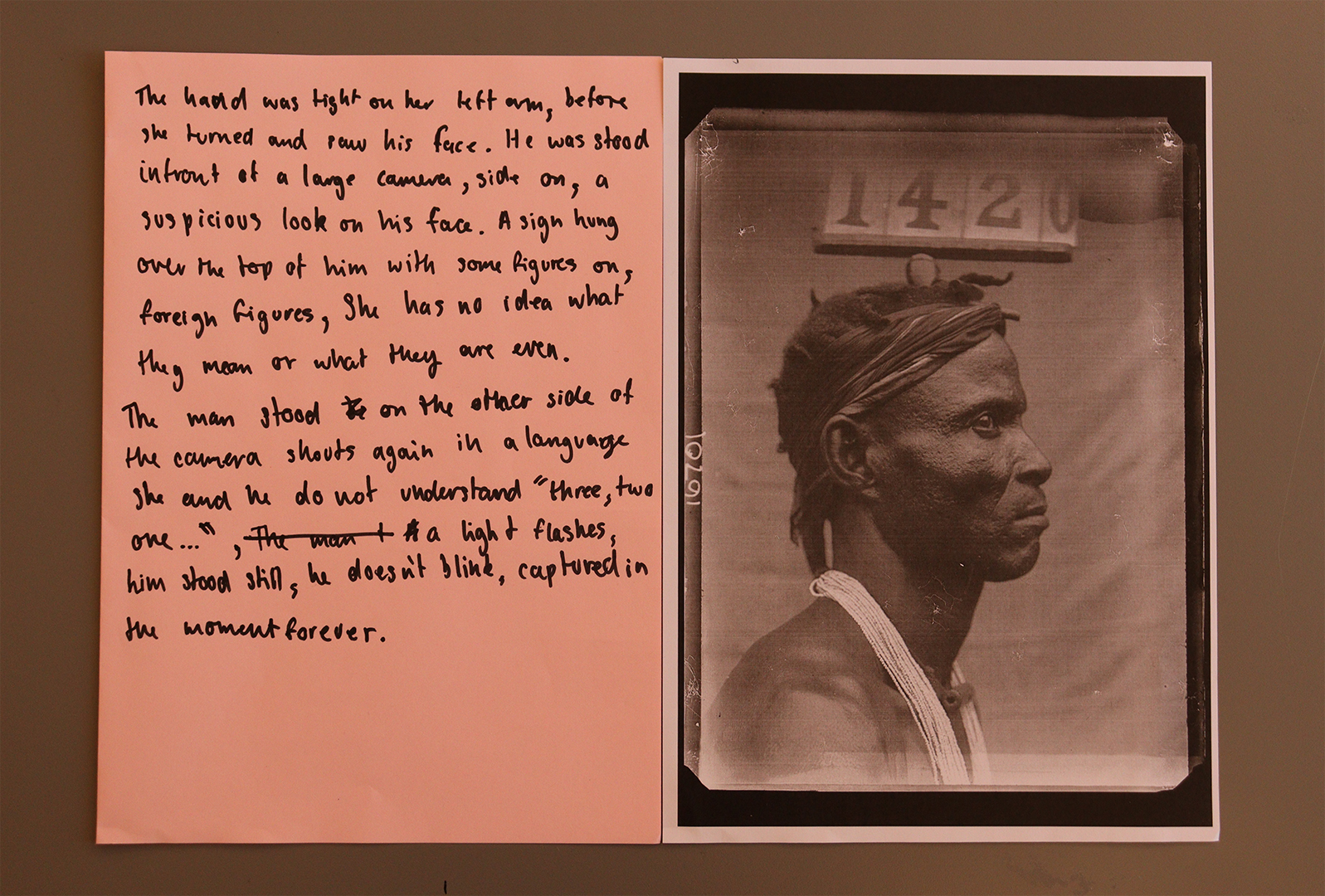

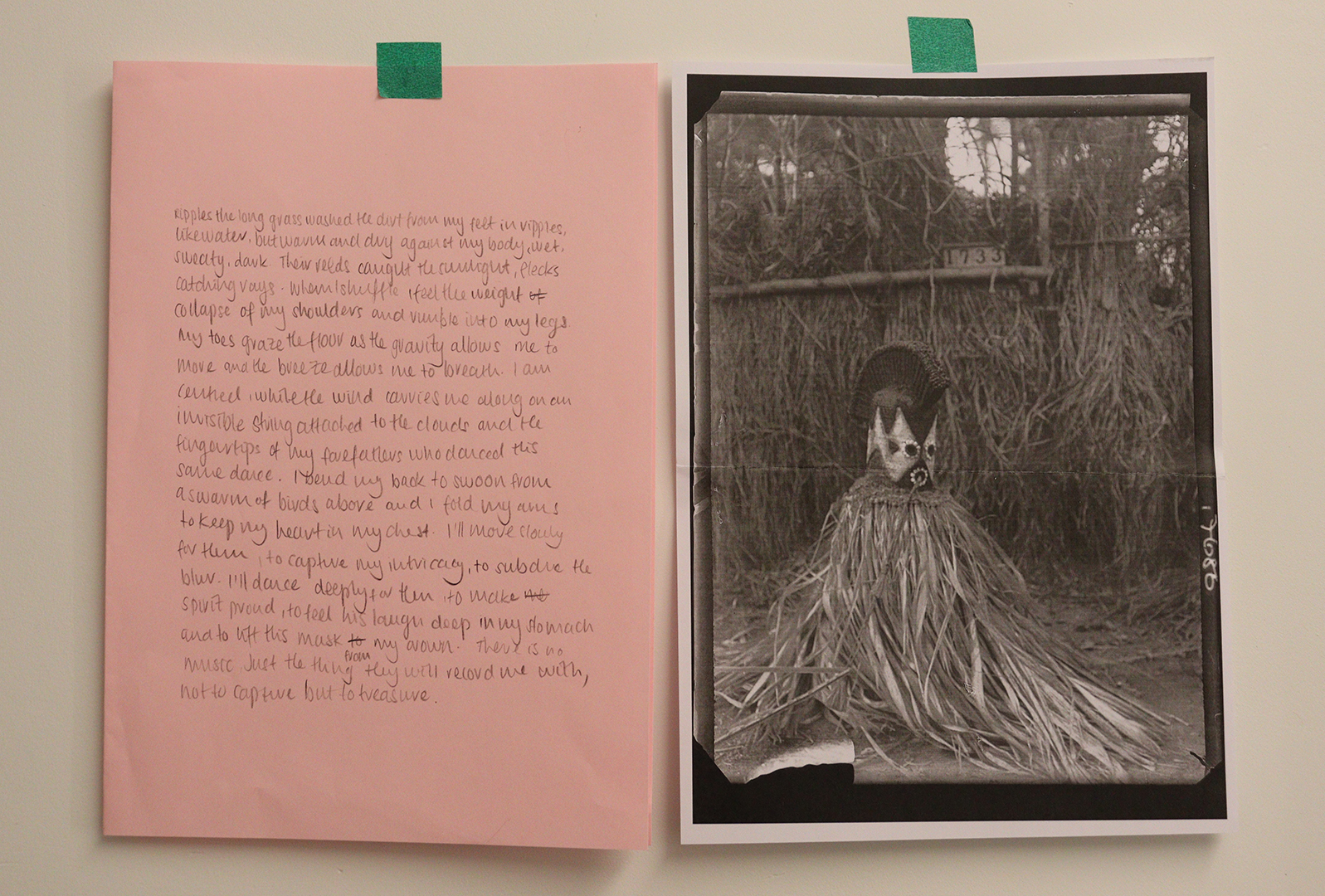

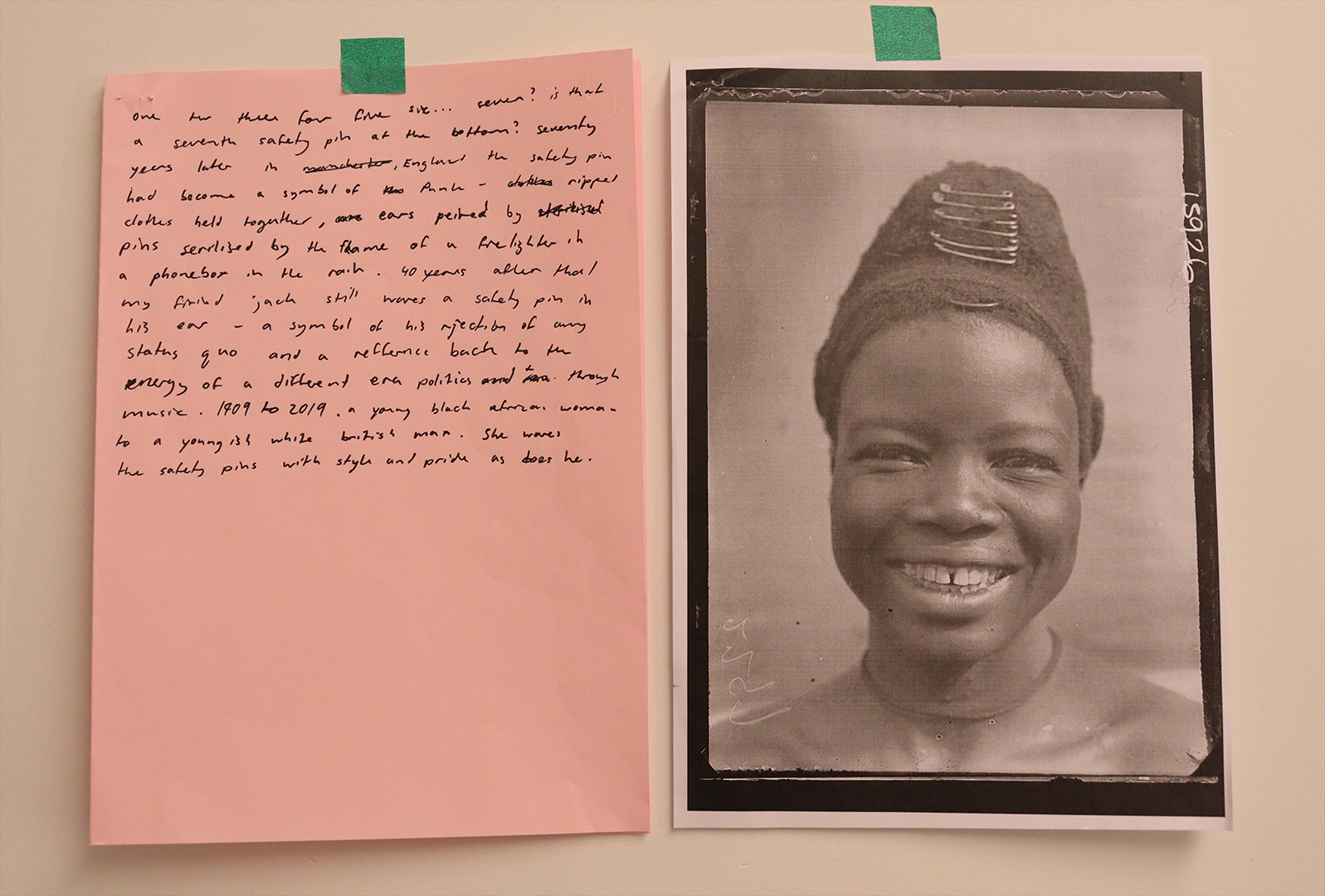

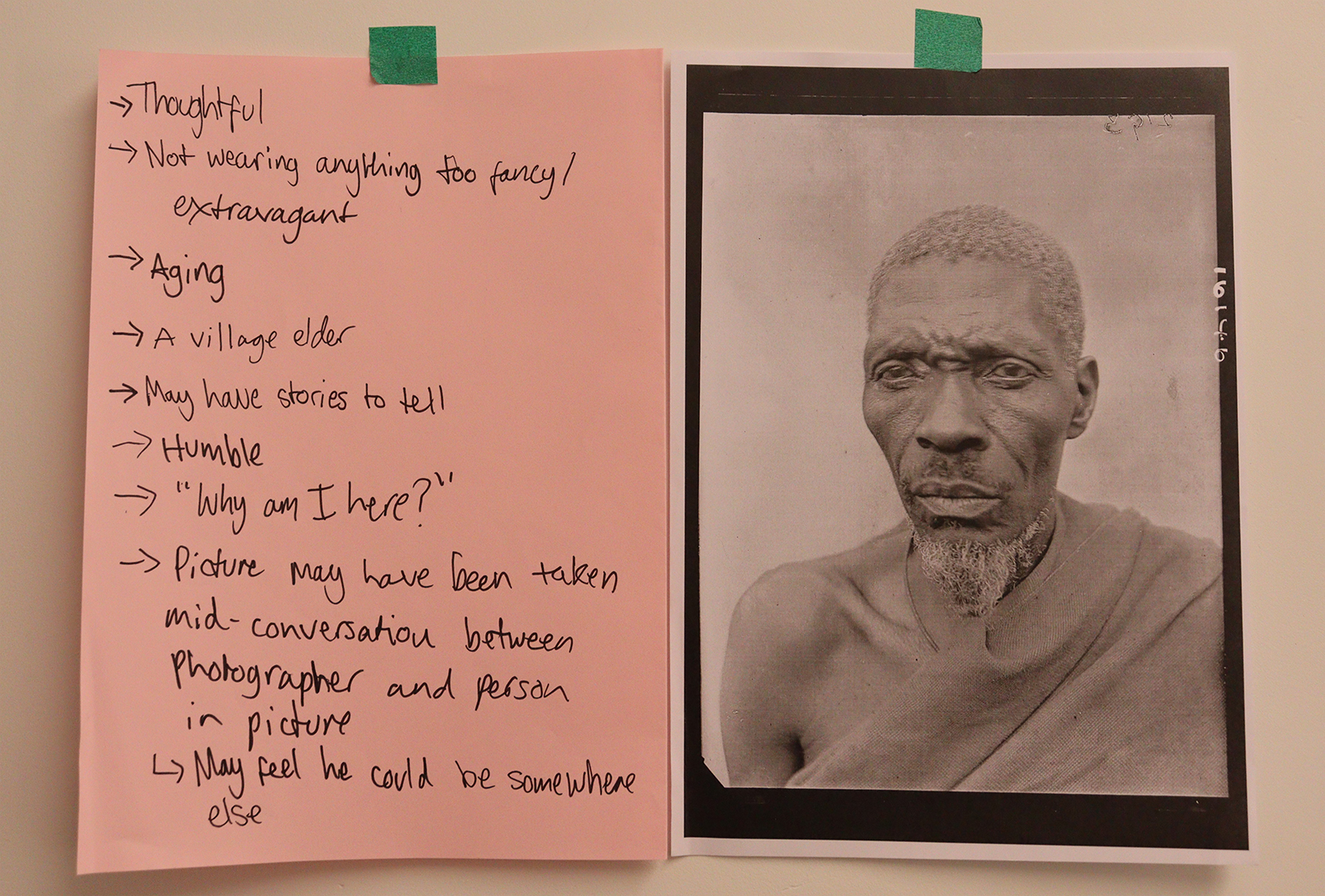

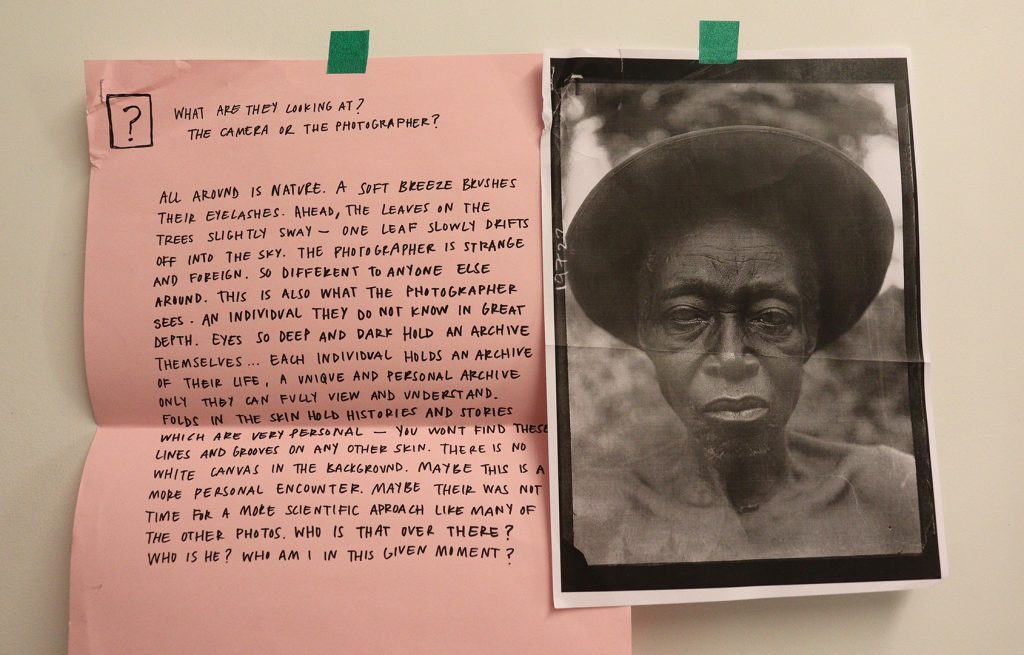

Resisting the practice, then, of allowing the eyes to ‘read’ silence in Northcote Thomas’ ‘voiceless’ photographic archive, we instead privileged alternative frequencies by listening closely to the images and expressing our discoveries in a free-writing exercise. Rather than finding misery in the archive, the Art Assassins wrote of joy, talent, romance and longing. It is here that the ‘low hum’of resistance to the colonial project might be found.

Confronting Northcote Thomas

Since the Art Assassins’ experience of Northcote Thomas had hitherto been exclusively through the archives of his anthropological surveys, I felt it was important to separate Thomas, the man, from his professional role as Government Anthropologist. Drawing on Paul Basu’s article ‘N. W. Thomas and Colonial Anthropology in British West Africa’, I attempted to take the Art Assassins on a journey that simultaneously elucidated what anthropological methodology looked like in practice, and lead the Art Assassins to reflect on whether we might potentially decolonize the anthropological tradition through making Northcote Thomas the object of inquiry.

Looking into his controversial legacy as illustrated by the comments made by Thomas’ peers as well as contemporary anthropologists, we considered how we might learn about Thomas and the period he was working in through various lenses, such as medical anthropology, or critical race theory.

Considering tales spread by his dissenters that he was ‘a recognised maniac in many ways’ (what might this tell us about the stigma of mental health in the 19th/20th century?) and the accusation that he brought ‘a certain amount of discredit upon the white man’s prestige’ (how might this complicate our understanding of Northcote Thomas as a puppet of the colonial state?), we were confronted with the possibility that we might in fact sympathise with Thomas, or at least consider him in a new light, particularly given the fact that he was sometimes a nuisance to the colonial project.

I encouraged us all to sit with the discomfort of these findings, whilst at the same time question what was at stake with any attempt to view him as a human being with the flaws and quirks of any other.

The unfolding discussion was rich, with the Art Assassins demonstrating yet again their interest in, and talent for, dealing with theoretically difficult concepts and disciplinary interrogations, such as whether anthropology was really the appropriate discipline to confront some of the challenges we were facing.

We all left the session buzzing with questions. Northcote Thomas had gone to Nigeria and Sierra Leone to find answers and provide solutions, and we realised that in order to ethically embark on this project, we had to part with the ideal of knowledge as a signifier of value. Surprising a lesson it may be, coming from someone who embodies the role of researcher-in-residence, we nonetheless learned that it is our ability to sit with uncomfortable questions that can provide the most intellectual and creative freedom and, hopefully, culminate in a practice that truly is decolonial.