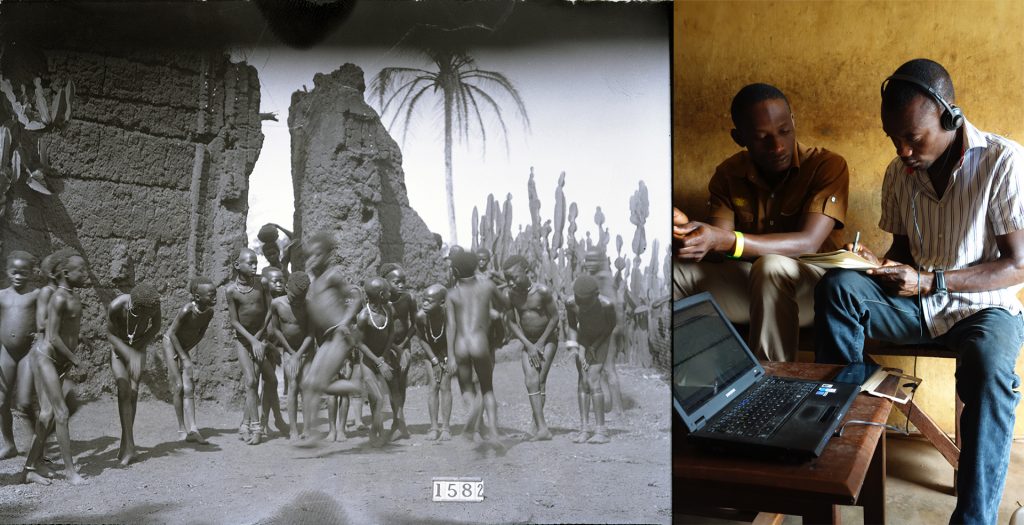

Northcote Thomas visited the Esan (or Ishan) towns of Agbede, Irrua and Ubiaja in August 1909. At the royal palace in Ubiaja, Thomas photographed some remarkable carved doors and house-posts. 71 years later, in 1980, the art historian Carol Ann Lorenz conducted research in Esanland as part of her PhD project Ishan Sculpture: Nigerian Art at a Crossroads of Culture (Columbia University, 1995). In this article, we revisit Lorenz’s unpublished notes about the Ubiaja carvings in the light of our own research as part of the [Re:]Entanglements project.

In 1980, Lorenz was able to document the remains of what she termed ‘figurated house-posts’ – or orẹ in the Esan language – in a number of towns, including 75 in Uromi, a short distance from Ubiaja. These sculptural posts supported the verandas of palaces and noble residences, providing a visual statement of the owner’s status and authority. At the time of Lorenz’s fieldwork, such posts were no longer made and those that survived were in a very poor state – some no more than mere stumps. Although the examples in Ubiaja were no longer in evidence, Lorenz noted the importance of Thomas’s photographs insofar as they provided a rare documentation of an assemblage of complete posts in situ.

Ubiaja palace complex

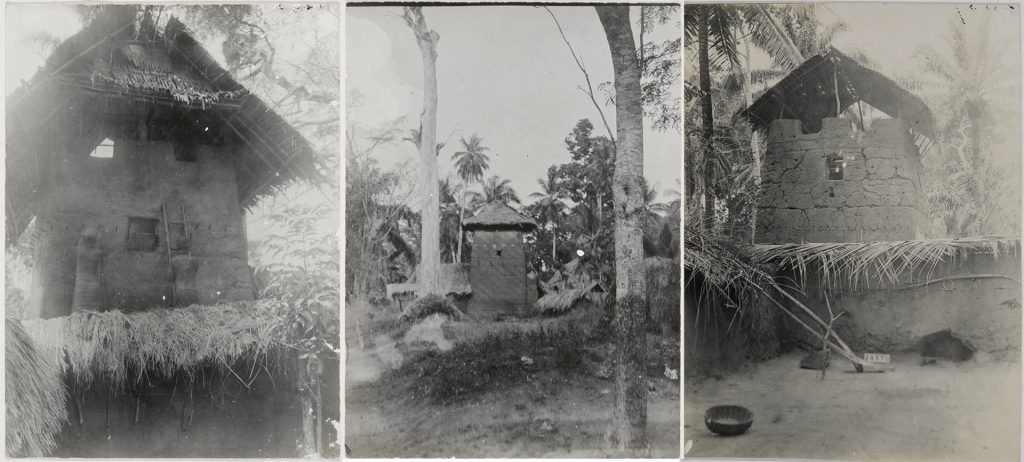

Lorenz was unable to find any oral traditions about the carvings in Ubiaja. She did, however, learn from the ruling Onojie (king) of Ubiaja, HRH Abumhenre Ebhojie II, that a fire had destroyed the palace in 1902. Evidently unaware that Thomas visited Ubiaja seven years later, in 1909, Lorenz made the incorrect assumption that he had photographed the palace sculptures prior to their destruction in the conflagration. It appears, rather, that the house-posts that Thomas photographed were part of a new palace, built after 1902, or of buildings that had not been affected by the fire. Indeed, we know from Thomas’s photograph register that he photographed at least two different buildings within the palace complex.

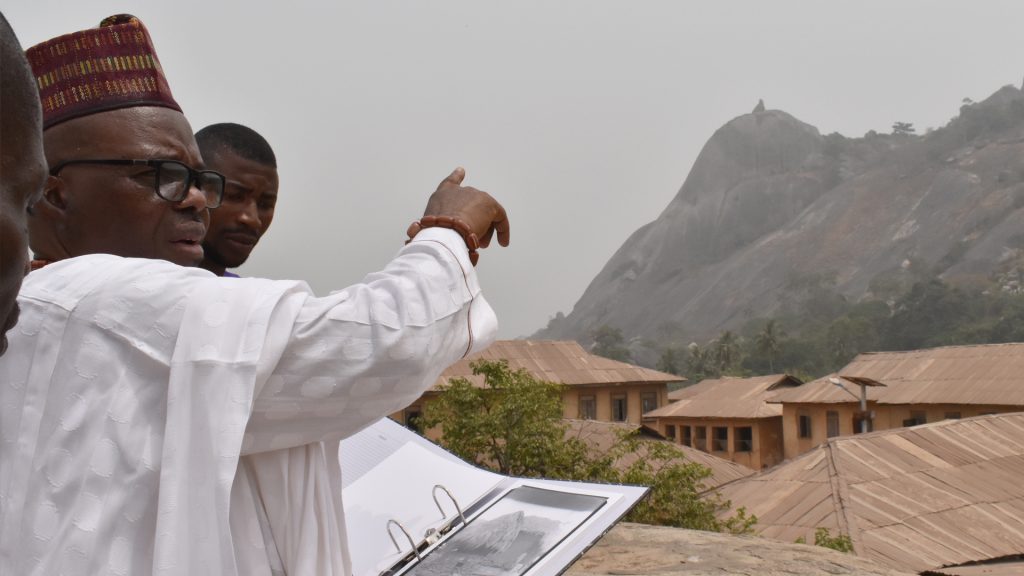

When we visited Ubiaja as part of the [Re:]Entanglements project, a brand new palace had recently been constructed for the reigning Onojie, HRH Curtis Idedia Eidenojie. Adjacent to this impressive new concrete structure are various generations of earlier earthen-walled palace buildings, many in a ruinous state. It was not possible to say with certainty if any of these were the remains of the palace that Thomas photographed in 1909.

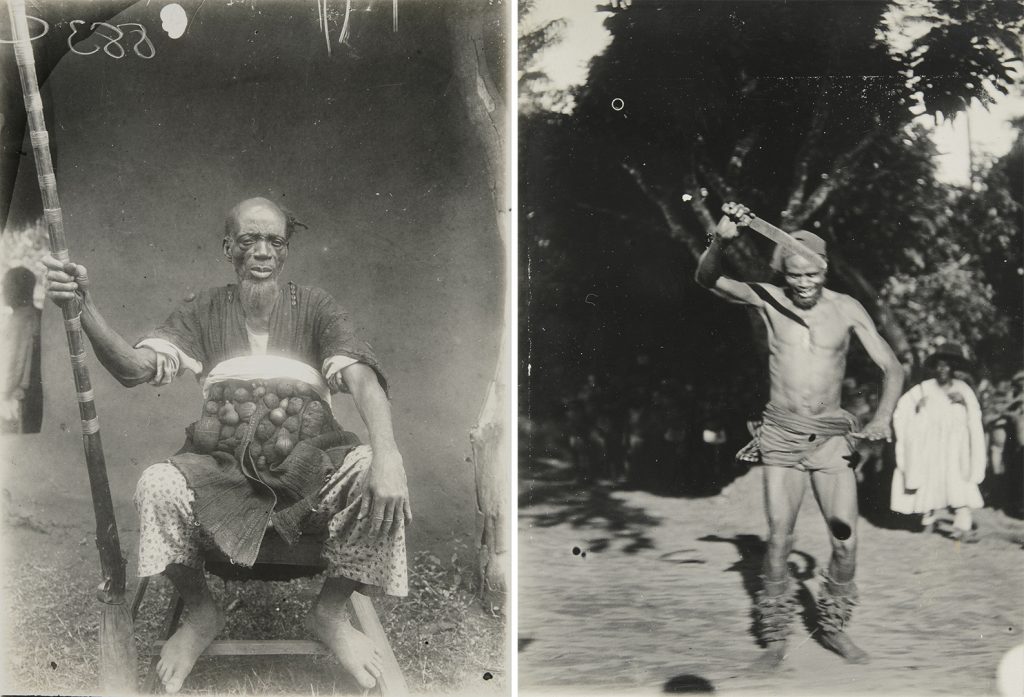

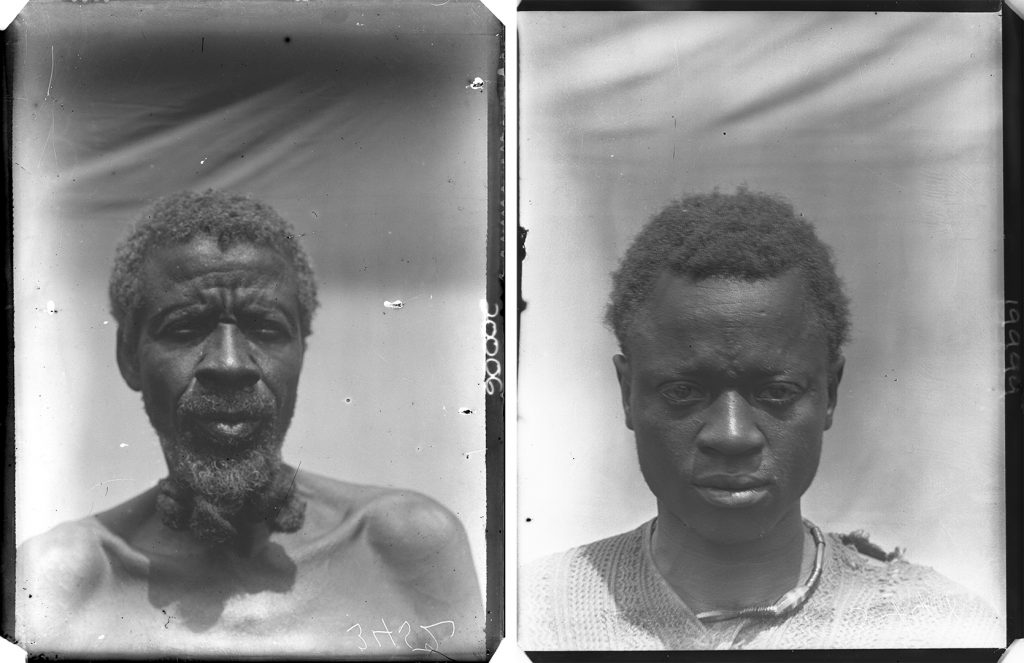

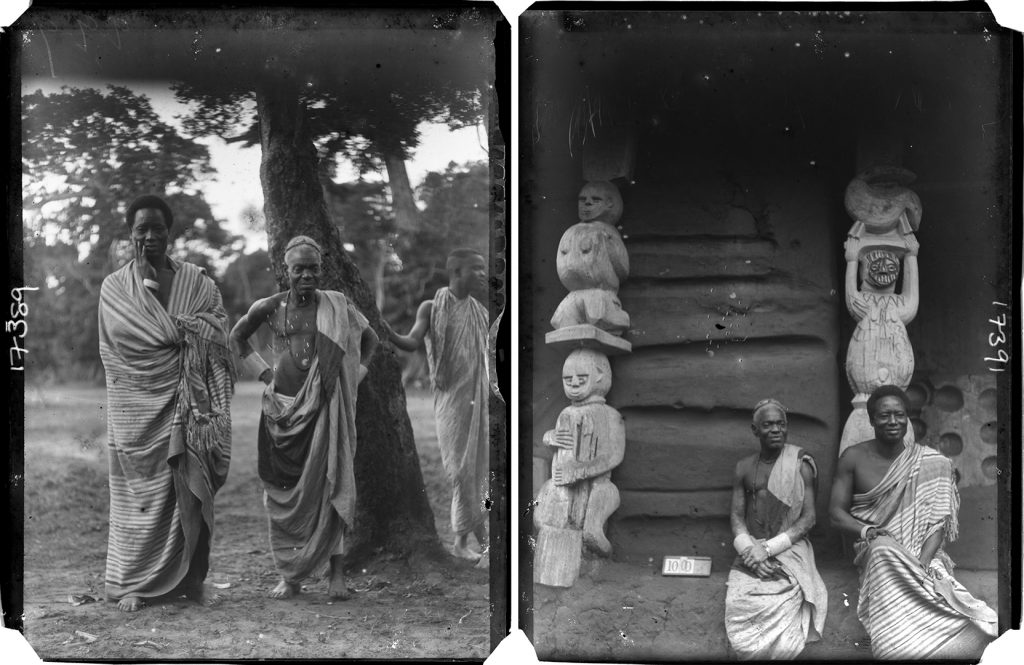

Thomas visited Ubiaja during the rule of Elabor, who reigned between 1876 and 1921. By 1909, however, Elabor was elderly and suffering from ill-health. In these circumstances, a power struggle existed between a senior member of the royal household, Prince Obiyan, and Elabor’s eldest son, Prince Ugbesia, over who should act as the Onojie’s regent. Thomas photographed Elabor alongside a man he labelled ‘Obiria’. During our fieldwork in Ubiaja, the name Obiria was not recognised and it was felt that this was an incorrect transcription of Ugbesia. Some of the doorposts photographed by Thomas and discussed by Lorenz are, according to Thomas’s photo register, from ‘Obiria’s house’.

House-posts

Lorenz provided descriptions of each of the house-posts photographed by Thomas. Regarding the house-posts in the photograph above right (NWT 1000), the sculpture on the left depicts two kneeling figures, one above the other with a platform between them. Lorenz reported that this configuration was unique in her survey of Esan sculptures, although it was common in Yorubaland. The sculpture on the right depicts a figure carrying a fowl or bird on a head tray, possibly representing an intended sacrifice.

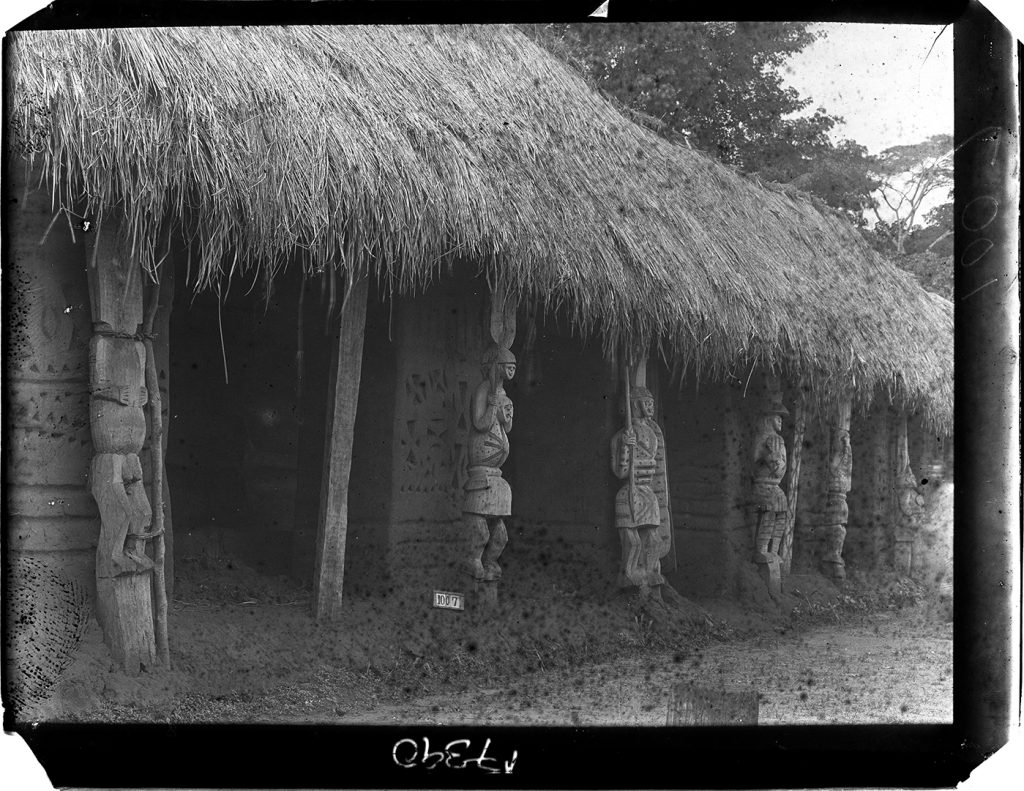

The house-post in the photograph above left (NWT 1002) is described as ‘depicting a female figure touching her breast with one hand and her full belly with the other. Her abdomen is decorated with incised patterns’. Lorenz described the house-posts in the photograph above right (NWT 1003) as ‘depicting a painted snake image on a plank post, and a three-dimensional trumpet blower’. While Lorenz identified all these sculptures as belonging simply to ‘the palace in Ubiaja’, those in the photograph above right (NWT 1003) can be identified in the photograph below, which Thomas’s labelled ‘Obiria’s house’. Although not the main palace, it is likely that this was located in the palace complex.

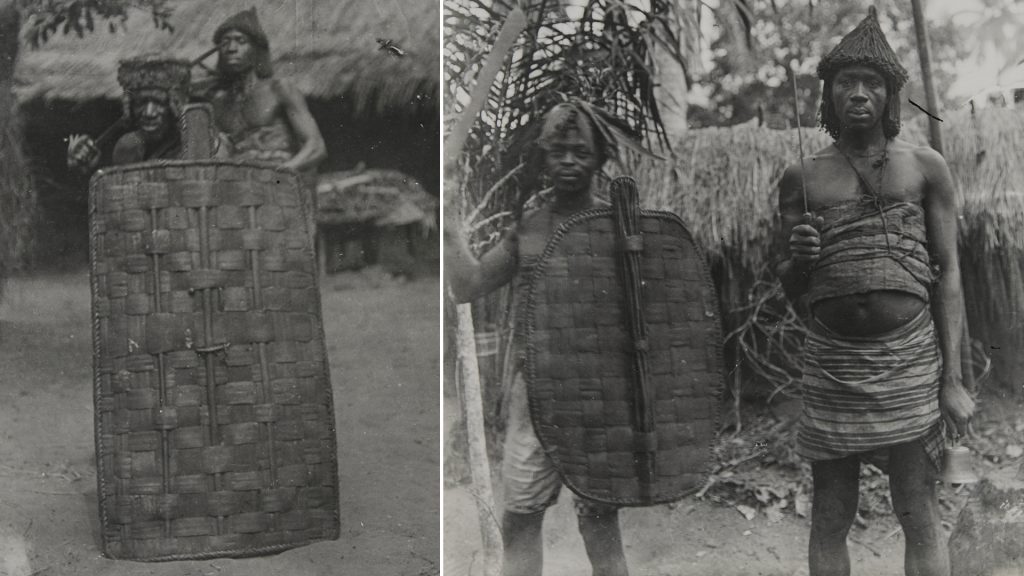

Lorenz described the sculptures in the photograph of what we now know to be ‘Obiria’s house’ (NWT 1007) as depicting (from left to right): ‘a naked male figure, a swordsman carrying a severed head, a warrior with a shield and spear, a man with a pith helmet, a trumpet player, and a seated king’. There is a strong formal consistency in the four central carvings (the swordsman, warrior, man in pith helmet and trumpet player), suggesting they were made together and were the work of a single artist or workshop. They also appear to be relatively recently carved, due to the lack of weathering or insect damage.

Although Lorenz did not comment on it, the post on extreme left of this photograph – that depicting ‘a naked male figure’ – is perhaps more interesting than it at first appears. Firstly, it has no head. Instead of a head, the post continues merely as a flat ‘plank’ to the roof joists. Could its head possibly be that held by the swordsman sculpted from the adjacent pillar? Secondly, the figure appears to be shackled around its neck and left leg to a pillar beside it. Pure speculation, but perhaps this figure represents the body of a vanquished enemy? Stripped, shackled and finally beheaded?

Although we cannot be absolutely sure that Obiria is the king’s son, Ugbesia, it is interesting to note that Ugbesia was known to be despotic and tyrannical. The Esan historian, Christopher Okojie, writes that with the decline in Elabor’s powers, ‘the light of the Ruling House of Ubiaja went out’ and was ‘replaced with darkness in which hatred, confusion, suspicion and bipartisan warfare’ reigned. As noted above, at the time of Thomas’s visit, there was conflict between Ugbesia and his competitor for the regentship, Prince Obinyan. This quarrel evidently split Eguare (the palace quarter) into two warring factions, which had a profound effect on the wider Ubiaja community. In 1914 Ugbesia was formally recognized as regent, but the following years were also spent embroiled in conflict until, in 1919, he died in ‘mysterious circumstances’, predeceasing his incapacitated father by two years.

In her notes on the above photograph of a palace courtyard (NWT 994a), Lorenz describes the house-post figures as depicting, from left to right, ‘a seated king, an ekpokin box bearer, an ujie group, two swordbearers, and a female figure nursing a child’. An ekpokin is a box used to carry gifts or tributes to the king. Ujie is music/dance genre in Esanland associated with royalty. According to Lorenz, these were common motifs in Esan sculpture.

Door panels

In addition to house-posts, Thomas photographed other sculptural forms in Ubiaja, including a number of carved doors and an agbala stool. The door carvings are quite distinct from the styles either of Benin or Igboland, of which Thomas photographed many examples. Lorenz argues that they are strongly influenced by Nupe door carving styles from the north, with discrete relief figures arranged in vertical rows. The Nupe had invaded the region to the north of Esanland earlier in the 19th century, and their influence extended to the Esan towns such as Irrua, Agbede and Ubiaja that Thomas visited. Unlike Nupe doors, however, the Esan examples include many representations of human figures, as well as the more typical representations of animals and inanimate objects.

Lorenz interprets the figure at the top right of the photograph above left (NWT 1025) as being a male noble (okpia) holding a segmented ukhurhe staff. He is positioned above a female figure (okhuo), below whose feet a horizontal female figure lies. Lorenz observes that this door appears to have been repaired. The centre panel featuring a human figure, profile of a monkey and a lizard, has, she suggests, been carved in a different style to the two panels that flank it. She also observed that this and the left-hand panel were placed upside down when the door was reassembled. The larger male figure at bottom left should be at the top, holding the royal symbols of ada and eben aloft.

Thomas’s photograph above right (NWT 1027) features scenes of violence, which Lorenz argues is a common theme in Esan carving. At the bottom right is an equestrian figure (ohenakasi), depicted in profile, wielding a double-edged sword (agbada). The male figure at top left, interpreted by Lorenz as a warrior, carries a grid-like shield, known as asa in Benin. The shield was made of sticks or palm ribs, which, as Lorenz argues, ‘would not offer much physical defence’. They were, however, ‘fortified with protective medicine (ukhumun), which enabled it to repel or catch enemy weapons’. This door also features a leopard (bottom left, recognizable from its tail which arches over its back), a crocodile eating another animal (top right), and a ceremonial eben sword – all three emblems are associated with royalty.

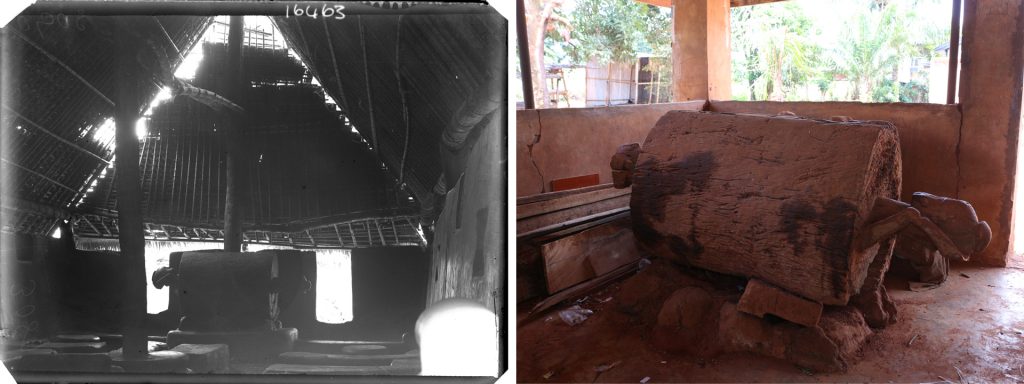

Agbala stool

Lorenz devoted a whole chapter of her thesis to a discussion of a type of courtly furniture, the agbala or stool of office. Like other items of regalia, such stools illustrate both similarities and differences between Esan and Benin City, where the equivalent type of stool is known as agba. Lorenz argues that Esan elites ‘appear to have required a locally carved stool of office which was similar enough to the Benin agba to retain its association with prestige and authority, but divergent enough to be a distinctively Esan product’.

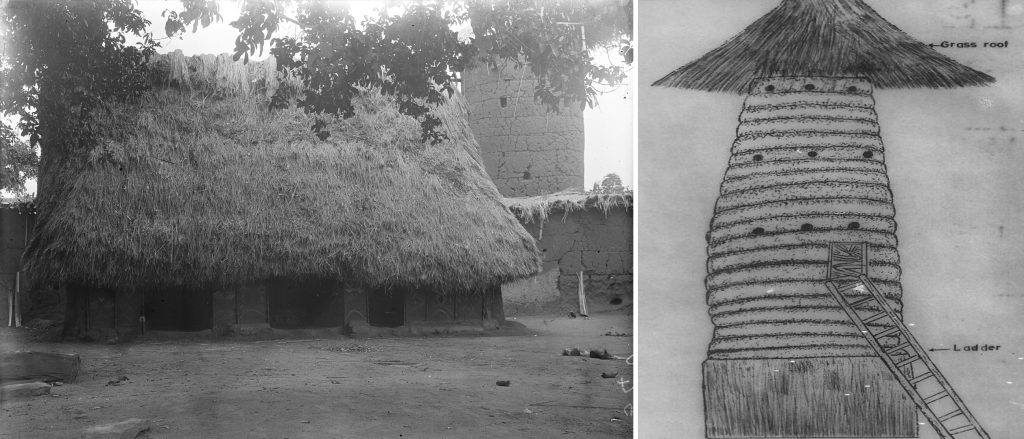

These stools were used exclusively by the Onojie or other hereditary chiefs on ceremonial and ritual occasions. Lorenz notes that it was particularly forbidden for the owner’s senior son and heir to sit upon them. The stools were kept in the ancestral shrine room and often served as a focus of offering to the ancestors. Thomas photographed one of these agbala stools in Ubiaja, and noted that they were equivalent to ukhurhe rattle-staffs, used to commemorate and honour the paternal ancestors.

Lorenz was able to locate nearly 30 examples of Esan agbala stools and identified three distinct styles. The example photographed by Thomas in Ubiaja is typical of what she terms the ‘ridged figural’ style, which feature highly-geometricized caryatid figures, carved in relief on the stretchers, often – as in this case – with arms upraised. The side panels also feature relief carvings, with a semi-circle cut away at the base to form two legs. Unfortunately, the design on the seat of the stool is not clear in the photograph.

Thomas did not photograph examples of wood carving in the other Esan towns he visited. He did, however, collect the side panel of another agbala stool in Irrua (see above right). This is an example of what Lorenz defines as an ‘openwork’ style, associated with the town of Uromi. Indeed, by comparing this panel with other complete stools, she argues that it was likely made in Uromi, even though it was collected in Irrua.

Esanland at a crossroads of culture

Through her analysis of Esan sculpture, including the examples documented by Northcote Thomas in Ubiaja in 1909, Lorenz’s main thesis was that Esan culture was essentially hybrid in nature. It was the mixture of Benin, Nupe, Yoruba and Igbo traditions that gave Esan art its unique character, as evidenced in these remarkable sculptural house-posts, carved doors and stools of office. Alas, these arts are no longer practised, and, due to the ephemeral nature of the materials, susceptible to decay and insect damage, and to collectors (Northcote Thomas included), very little of this sculpture has survived. We found not even a memory of it at the palace in Ubiaja.

Perhaps a new generation of contemporary Esan artists will one day discover Thomas’s photographs of these amazing sculptures and revive – or reinterpret – the tradition?

Further reading

- Lorenz, C. A. 1995. Ishan Sculpture: Nigerian Art at a Crossroads of Culture, Unpublished PhD thesis, Columbia University.

- Okojie, C. G. 1960. Ishan Native Laws and Customs (Yaba: Okwesa)

- Ukpan, J. A. 2010. History and Culture of Ubiaja (Benin City: Obhio)