Working through the photographs, sound recordings, artefact collections and written accounts that constitute the archive of Northcote Thomas’s anthropological surveys in West Africa, the turbulence of the times in which these materials were assembled is not immediately apparent. Of course, it can be argued that the archive as whole is a trace of colonial violence. As the historian Nicholas Dirks reminds us, colonial conquest was the result not only of military force but was made possible and sustained through ‘cultural technologies of rule’. Regardless of whether they actually achieved their governmental objectives, Thomas’s surveys were certainly intended to contribute to the consolidation of British ‘indirect rule’ in what were then the Protectorates of Southern Nigeria and Sierra Leone.

It is perhaps indicative of the thoroughness with which local resistance to colonialization had been quashed that Thomas was able to travel around so freely over the six years of his surveys between 1909 and 1915. Thomas worked in the towns of Somorika, in 1909, and Agulu, in 1911, both a mere five years after they had been ‘pacified’ through British military operations; he travelled extensively in areas of Asaba District that, until two years previously, were centres of anti-colonial resistance in the Ekumeku wars; his research in Sierra Leone took place in locations that had seen violent conflict in the Hut Tax War of 1898; and he spent months working in Benin City, just 12 years after the infamous Punitive Expedition of 1897. Thomas did not, of course, travel alone – his entourage would have included porters and assistants, and we know from correspondence that, at least some of the time, he was accompanied by a member of the police force. There is just one photograph, from Thomas’s 1910-11 tour, in which a uniformed police officer can be seen – we don’t know whether he was ordinarily stationed at the location, or accompanied Thomas there.

The years prior to the formal British colonisation of Nigeria and Sierra Leone were also turbulent. Conflict was ever present; often driven by competition for land, resources (including slaves) and control of trade routes. Much of this conflict was directly or indirectly connected to the Transatlantic trade in enslaved people and other commodities, but also resulted from antics of expansionist states in the interior (the incursions of Samori Toure’s Wassoulou Empire into northern Sierra Leone, for example, or Nupe raids into the north of present-day Edo State in Nigeria). Traces of these conflicts – sometimes mislabelled as ‘inter-tribal wars’ by the colonists – are more evident in the materials Thomas assembled during the anthropological surveys.

Fortified hilltop towns

The longue durée of conflict in pre-colonial Southern Nigeria and Sierra Leone is evident in the very location of many of the communities that Thomas visited. Town sites were often selected so as to make use of the natural features of the environment so that the community could be more easily defended against attack. This is most obvious in settlements in upland areas, for example those located in what were known at time of Thomas’s surveys as the Kukuruku Hills in the north of present-day Edo State, Nigeria, or in Koinadugu in north-eastern Sierra Leone. Many of the towns that Thomas visited and photographed in these areas occupied fortified hill-top locations. As a result of the ‘imposed peace’ that accompanied British colonisation, these settlements were subsequently abandoned and the towns moved to more accessible locations.

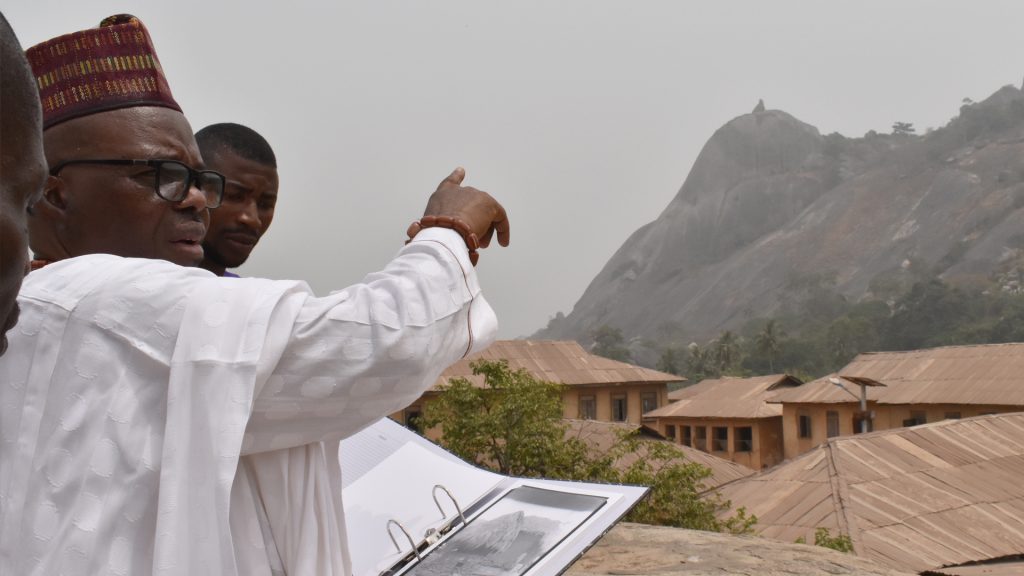

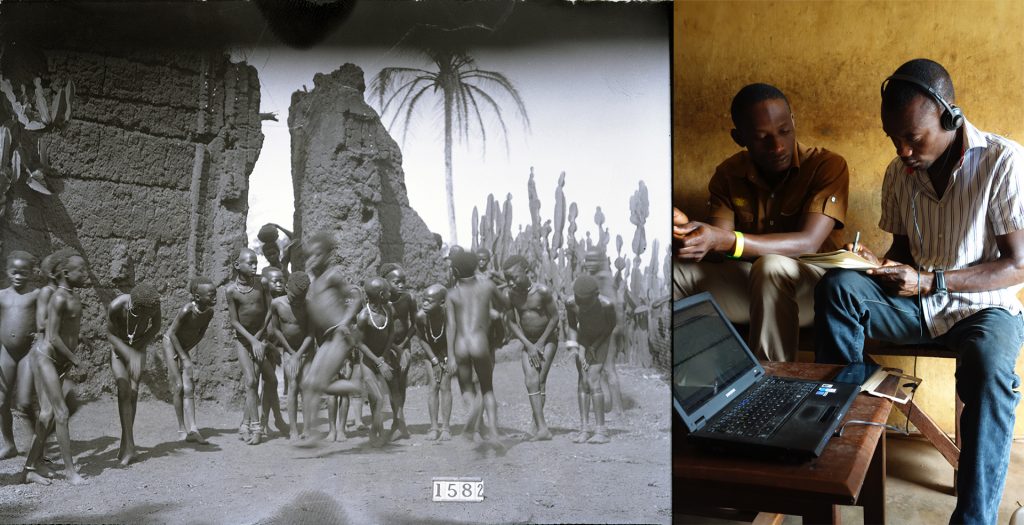

When we have brought Thomas’s photographs back to places such as Somorika, Okpe, Otuo and Afokpella in north Edo, or Yagala in Sierra Leone, community members are usually very interested to see what their old hilltop towns looked like when they were inhabited. In some cases, such as Yagala, the old towns were not abandoned until the 1950s and elderly members of the community have childhood memories of the places. Most community members, however, have known the old sites only in their abandoned state and through the many stories that are told about them. Many such stories relate to the heroism of warriors or the ingenuity of the community in repelling attack. The Imah of Somorika, HRH Oba Sule Iadiye, for example, regaled us with stories of the British attack on Somorika in 1904, which, while ending in defeat, is regarded as a moral victory.

In Yagala we were told the story of the famous warrior Suluku, from Bumban, who came with a war party, threatening attack. As they climbed one of the roads to the hilltop town, they came upon an old woman knitting. Suluku informed the woman that they had come to collect payment from Yagala. She gave him her knitting and said ‘Here it is, take it’. Suluku continued on his way to the town. Afterwards, he left by another route only to find the same old woman by the side of the road. He asked how she came to be there before them. ‘This is my place’, she answered, ‘I am not an invader like you’. Suluku thought that she had special powers and asked her for help. She agreed to help, but only in return for gifts. Suluku agreed, and said he would send his brother, Pompoli, from Bumban, with the gifts. Pompoli duly returned bearing the gifts and the old woman gave Suluku some of her magical powers. Incidentally, while Suluku died in 1906, Thomas photographed Pompoli when he visited Bumban in 1914.

Defensive structures

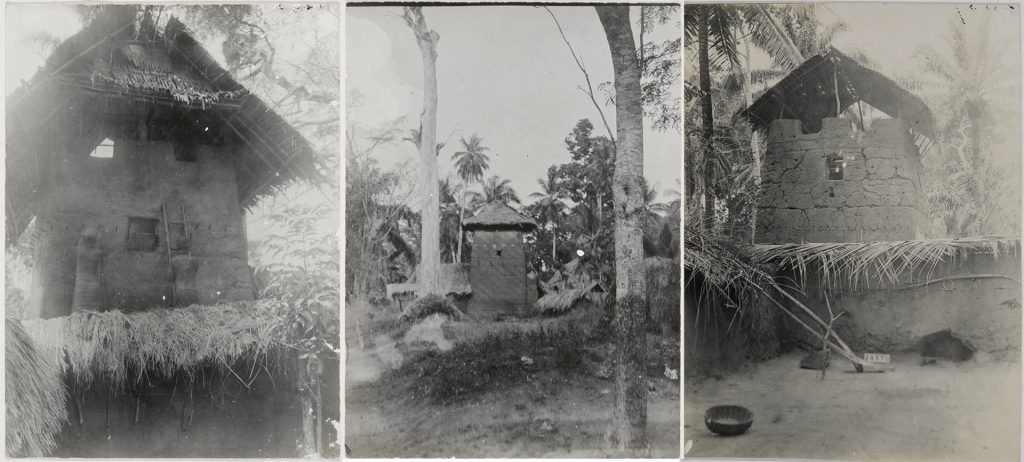

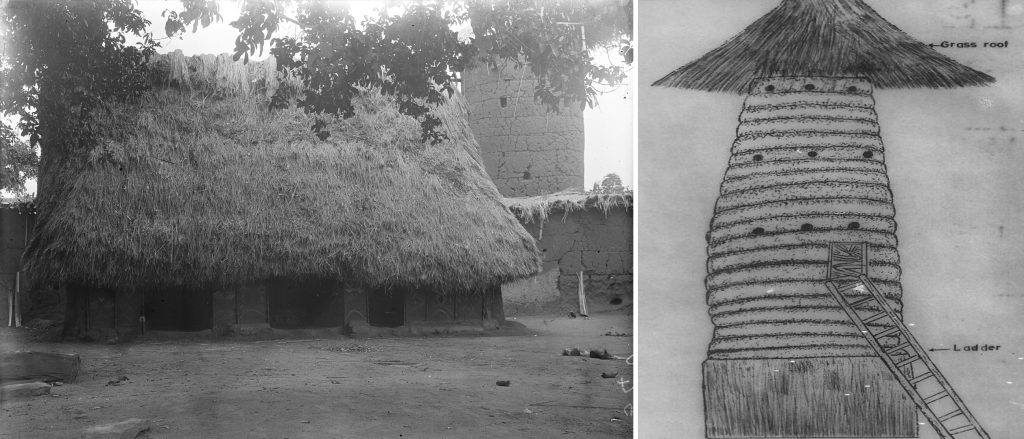

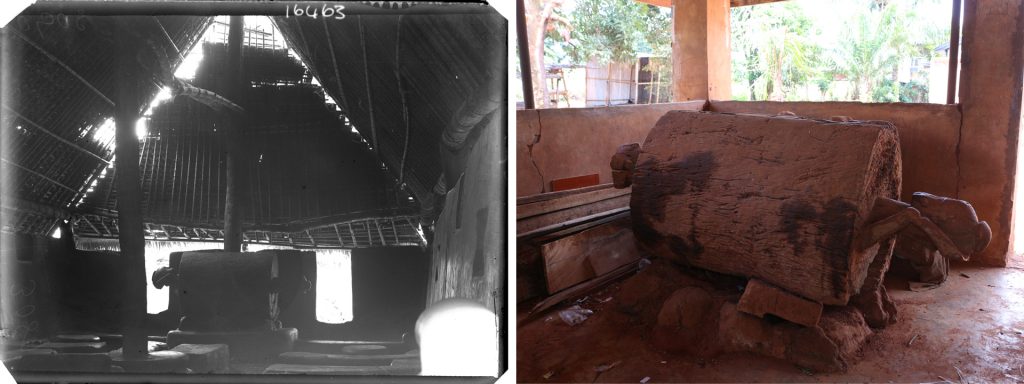

In the lower lying, forested areas of Awka District, which was the focus of Thomas’s 1910-11 tour, Thomas took several photographs of fortified watchtowers. They are known in Igbo as Uno-aja. None of Thomas’s fieldnotes survive from this tour and he did not publish anything about these structures, so we don’t know if he collected any information about them. Oral traditions about the towers survive, however.

These towers were typically two or three storeys high and were accessed through a small doorway on an upper floor, reached by a ladder. They served as both a look-out tower and a refuge, particularly for women and children, when a settlement was under attack. Some were rectangular in plan, such as those in the photographs above, others circular, as in the example at Awgbu (see below).

Professor Anselem Ibeanu, currently head of the Department of Archaeology at University of Nigeria, Nsukka, did some research on these watchtowers in the 1980s. While the majority had long-since collapsed or been pulled down to make way for new buildings, he managed to locate a small number that had survived, even though in ruinous condition. One of these was called Okpala Obinagu in Awgbu, supposedly named after the founder of the community who erected it. The tower can be seen in the background of one of Thomas’s photographs of the obu (meeting house), probably of Chief Nwankwo of Awgbu, who Thomas also photographed.

Professor Ibeanu was able to speak to the elderly great-grandson of the builder of the tower, and was able to draw a reconstruction of what it had once looked like based on the oral accounts. This matches Thomas’s photograph with surprising accuracy, particularly its construction from concentric mud courses, each of which was allowed to partially dry before the next course was added, and the small apertures for windows. Interestingly, in Thomas’s photo register, he captions the tower a ‘storehouse’, suggesting that it was repurposed once the threat of attack subsided.

Re-enactments of warfare

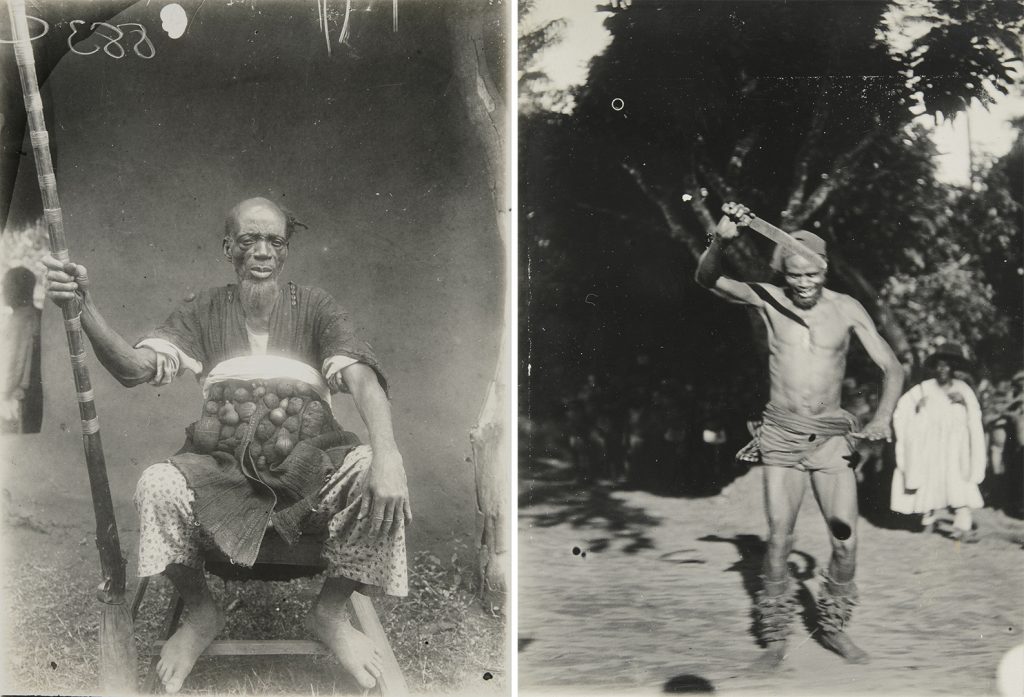

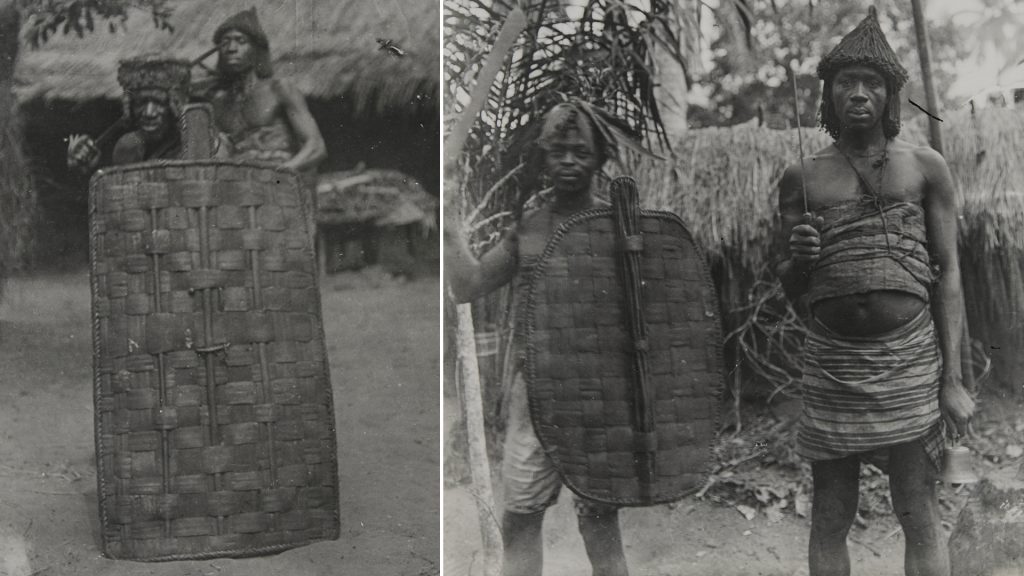

Thomas seems to have struggled to obtain information about the conduct of war – perhaps his informants didn’t want to give away military secrets to the colonialists! He did, however, photograph men in ‘war dress’ and witnessed demonstrations of ‘mock battles’.

There is a wonderful photograph taken in Sabongida in 1909 of a ‘chief’ (unfortunately Thomas doesn’t name him) posing with a magnificent dane gun and wearing war dress. The chief’s gown is covered in amulets, and the protection it offered was more magical than physical. Later the same year Thomas witnessed the annual Ebisua dance at Fugar. Community members in Fugar readily identified the photographs of this event when we visited. Ebisua is a war dance performed annually by the Uruamhinokhua age grade in honour of the war god Ituke. The men clothe themselves in their war dress for the dance, and, brandishing their weapons, reenact their valiant acts of the preceding year. It is an opportunity for the fighting men to show off their strength and military prowess. We were told that, in times of war, men would display the severed heads of enemies they had killed.

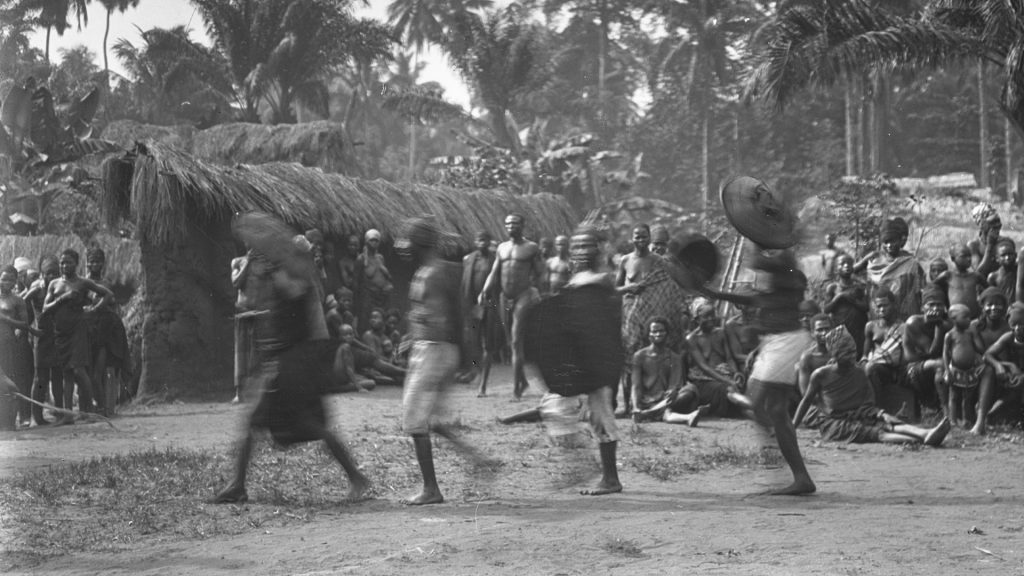

Thomas photographed another interesting event in Awka in 1911. According to the sparse notes accompanying the photographs, they were taken at a funeral of a man killed in war. (We do not know if this was a re-enactment staged for Thomas, or an actual funeral.) Before an assembled crowd, a group of warriors parade in their war dress, carrying swords and shields. In some of the photographs they appear to be staging a mock fight (see the photograph at the top of this article). Probably during this same event, Thomas made a wax cylinder phonograph recording of ‘Igbo war shouting’.

Thomas also appears to have arranged for some of the participants in the funeral to pose for him to demonstrate traditional fighting techniques.

Memories of Okoli Ijoma

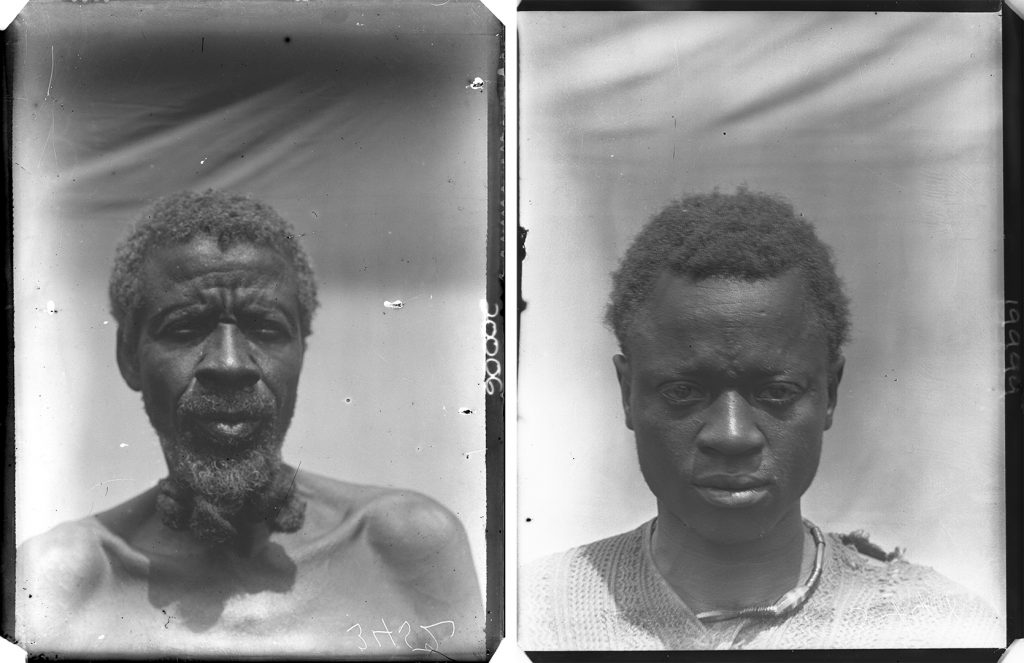

Not all traces of conflict are so legible in the archive; some traces only reveal themselves in the unexpected comments of community members in response to particular images. This was especially apparent in our fieldwork in the area around Awka, in present-day Anambra State, Nigeria. In virtually every town in which we conducted fieldwork, the archive photographs provoked stories of wars with the notorious Okoli Ijoma (‘Okoro Ijomah’ in the Aro dialect). Indeed, it was often because of the threat of attack from Okoli Ijoma and his mercenaries that towns formed alliances with the British, which resulted in a more insidious form of colonisation.

Okoli Ijoma was a powerful warlord from Umuchukwu in Ndikelionwu, a few miles to the south-east of Awka. Ndikelionwu had been founded in the eighteenth century as part of the expanding Aro empire. The Aro, with their homeland at Arochukwu in present-day Abia State, had established a major slave trading confederacy with a powerful military base, often supported by mercenaries. They settled throughout Igboland, forming alliances with some communities, while preying upon others. They are credited with introducing firearms into the region.

Conflict with Okoli Ijoma’s forces would have still been fresh in the memory of communities around Awka at the time of Thomas’s anthropological surveys, and the photographs he took of both people and places still bring to mind that dangerous time – even after 110 years. In Nibo, for example, we were told how the great ikolo drum would be sounded as an alarm of impending attack. It was a signal for the women and children to disperse to refuges, and for the men to gather in preparation for the fight. To save Nibo from further attack, Ezeike Nnama Orjiakor of Nibo formed an alliance with Okoli Ijoma, arranging for his younger sister to marry Okoli’s son, Nwene Ijomah. Nnama became a deputy in Okoli Ijoma’s court, but, later, as the threat of reprisals from the British mounted, he switched allegiance, while Okoli Ijoma fought on.

In other towns, allegiances were similarly divided. In Amansea, for example, community members were able to identify a photograph of Chief Nwaobuana, a well-respected leader who later became a Warrant Chief. He is credited with curbing the excesses of Okoli Ijoma and defending the town from attack. Another man, Nwene, was also identified, however. Nwene was the ‘black sheep’ of the community, and was known to take stubborn children from their parents and sell them to the Aro traders. The era of Aro slave trading was brought to an end with the British attack on Arochukwu in 1901. Okoli Ijoma died in 1906.

Read more about Okoli Ijoma and the ‘Ada wars’ at the Ukpuru blog, which is also illustrated with photographs from the Northcote Thomas archives.

Pax Britannica?

The coming of the British must have been met with ambivalence. On the one hand, alliance with the Europeans offered protection from local aggressors. On the other hand, of course, this led to the imposition of British colonial rule and the transformation of culture and society. Thomas’s anthropological surveys were carried out during this transformative moment, when new freedoms of the ‘British Peace’ could be appreciated, while the loss of self-determination under colonial rule was perhaps not yet fully apparent.

Some of the stories recorded by Thomas speak powerfully of this time of change and are therefore important historical sources. When local community members in Okpekpe, in the north of present-day Edo State, helped us translate recordings Thomas made there in 1910, it was interesting to listen to their interpretations. One recording compared past and present, celebrating the fact that children could now wander about freely and the town was now safe. We were told this related to the British defeat of the Nupe in 1897, who had, it was explained, on the one hand, brought Islam to Okpekpe, and, on the other hand, captured its people and sold them into slavery.

Godwin Gejele, from Okpekpe, provided the following translation of the recording from the Ibie language:

Eyia bhe amho

We’re coming today

Imiegba ana mhia je, ukha la mhi ayo tse we namhe

I’m going to Imiegba. If you get over there, extend my greetings

Ukha lamhi Imiakebu tsa Adogah na mhe tse we khu namhe, vhe wegbe omo mose ali omo kposo

When you get to Imiakebu extend my greetings to Adogah. I really appreciate him. I pray that God will bless their male and female children

Eye bi na agbo nele ali ona uhiena ono gwuo so mhi ne. Omo ovhe lasa ne na now li vho, ogbo kho oshie yele asha kha sha

In the olden days or in the present, which one is the better to live in? We can see in the old days, a child is not allowed to go out anywhere. Now one can go everywhere. Everywhere is safe.

Oso mhi ni bo, omue mhe gbe

We’re grateful to the white man who had come to teach and taught us many things

When we discussed this recording, elders explained that the speech was delivered in the style of a town crier. This raises the question of whose message the speaker was communicating. Does the speech convey a genuine sense of gratitude to the ‘white man’ for removing the threat of Nupe slave raids, or is this propaganda dispatched from the new invaders?

Further reading

- Cohn, B. S. 1996. Colonialism and its Forms of Knowledge. Princeton University Press. (Foreword by Nicholas Dirks)

- Falola, T. 2009. Colonialism and Violence in Nigeria. Indiana University Press.

- Ibeanu, A. M. 1989. ‘An Igbo Watch Tower (Uno-aja)’. Nyame Akuma, 31: 28-9.

- Ohadike, D. C. 1991. The Ekumeku Movement. Ohio University Press.