[Re:]Entanglements project conservator, Carmen Vida, provides insights into some of the conservation techniques used to clean and consolidate a remarkable Igbo maiden spirit mask collected by Northcote Thomas in 1911, and how close examination can tell us more about the mask’s biography both before and after it entered the museum.

One of the most visually striking objects that has come to the UCL Conservation Lab in preparation for the [Re:]Entanglements exhibition at the University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology is an Igbo maiden spirit mask collected by Northcote Thomas in Agukwu-Nri, present-day Anambra State, Nigeria, in 1911.

The maiden spirit (agbogho mmuo) is one of the most celebrated Igbo masquerade types. Although danced by men, the masquerades – manifestations of ancestral spirits – represent ideals of youthful femininity. The carved, wooden masks typically have fine facial features, with thin, straight noses, small mouths and light complexions, often decorated with uli designs or tattoos. They often have elaborate hair-styles, adorned with crests, coiled plaits and combs. They wear tight-fitting, vibrantly coloured and patterned appliqué costumes, which again evoke uli and other body painting designs. They dance mainly for entertainment, including at the annual Ude Agbogho or ‘Fame of the Maidens’ festival. Thomas collected two examples of the masks in Agukwu-Nri.

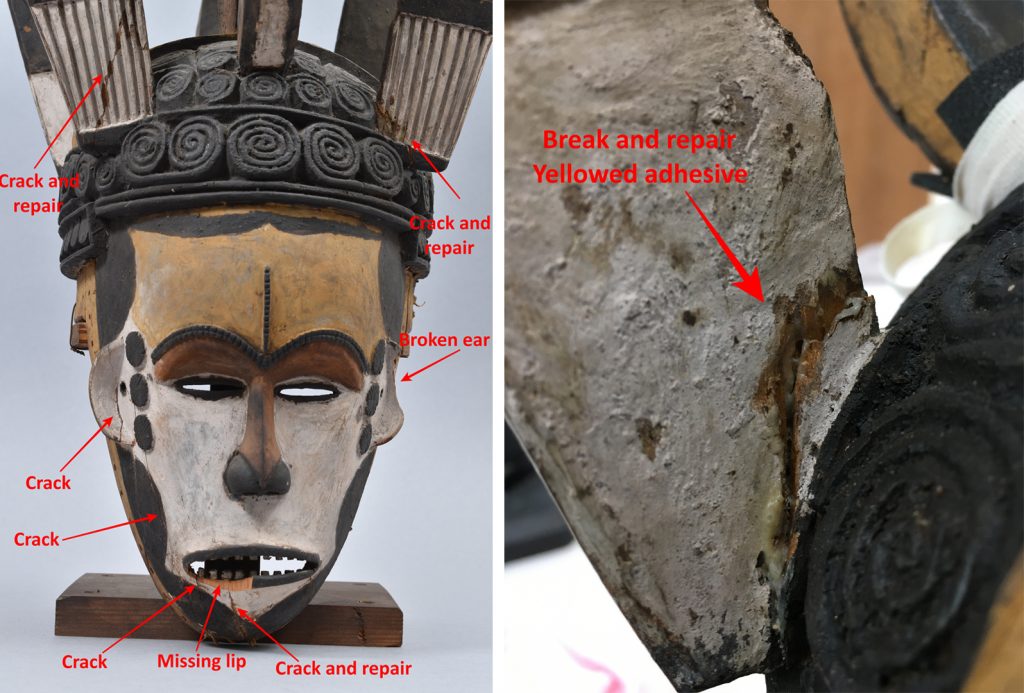

The mask we have been working with is a particularly fine example. It has a yellow and white face with black tattoos or scarification marks over the eyebrows, down the forehead and on either side of the eyes. Great detail has been paid to the carving of the hairstyle and of a tall, elaborate headdress that comprises a crest, four combs extending upwards and two stands surmounted by birds in between. The crest is made up of a large diamond-shaped section that is flanked by two horns that support two curved sections with upturned bells above. The painted decoration on the mask used red, black, yellow and white pigments. At some point, probably in the mid-20th century, the mask has been secured with copper wires onto a wooden mount.

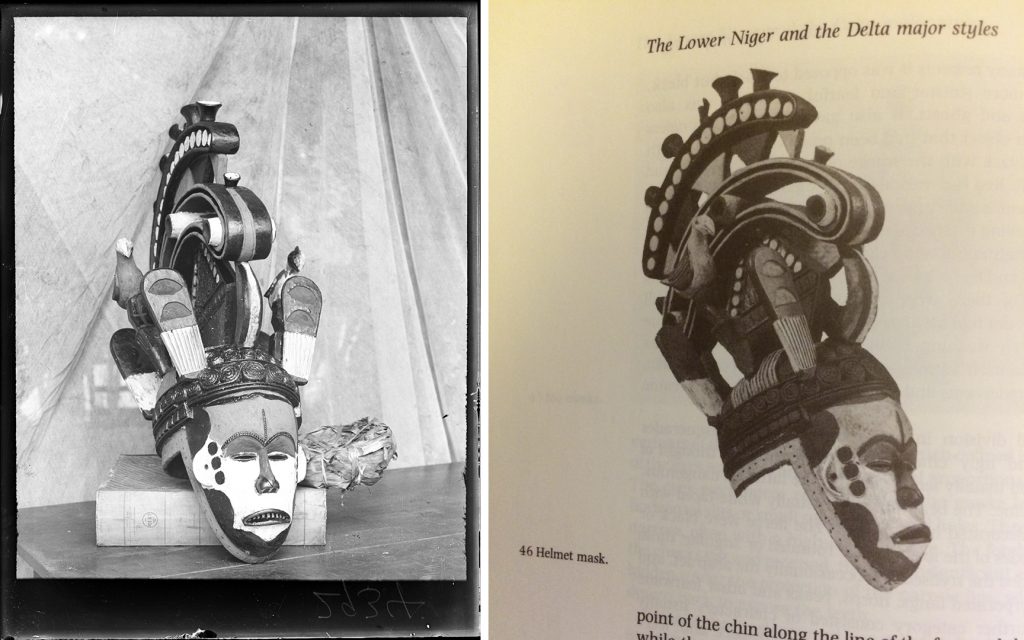

Thomas made a number of photographs of agbogho mmuo dancing at Awka in December 1910 and March 1911, and also photographed the masks he collected in Agukwu-Nri later in 1911. There are no photographs, however, of the masks he collected being performed and we do not know for sure whether they had been used in dances before Thomas acquired them or if he obtained them directly from the artist(s) who made them.

Although Thomas did acquire complete masquerade costumes during his 1909-10 Edo tour, it does not appear that he did so on his 1910-11 Igbo tour. (There is a complete agbogho mmuo costume on display at the Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology, but provenance is unknown.) That there were additional costume elements attached to the mask we are focusing on here is, however, evident from some fibres that remain attached to the rows of holes that run around the edges of the mask, especially in the area of the jaw and chin.

Unusually, Thomas made quite detailed notes about the mask. He records the name of the type of mask as Isi abogefi – Isi meaning ‘head’, while abogefi may be a dialect variation or erroneous rendering of agbogho, meaning ‘girl of marriageable age’. He notes that the carved bird on one side of the head represents a black pigeon (ndò), and that on the other side a parrot. The central crest he records as isi nkpo umu nwayi, a representation of a headdress women wear for dancing. Thomas records the sources of the four pigments: the black (oji) and yellow (èdò) pigments are derived from trees, red (ufie) is from camwood, and white (nzu) from chalk/white clay. He goes on to explain that the mmuo comes out to dance at the feast of Anuoye during the dry season. Anuoye is a goddess of protection in Nri. He writes that the mmuo will only dance for half a day, once a year. He goes on to detail the sacrifices made to her, and how these are later cooked and redistributed by the young men who perform the masquerade.

Conserving Isi abogefi

In preparation for the [Re:]Entanglements exhibition, the mask required conservation because there were issues with its stability and appearance that needed to be addressed. The initial condition assessment of the mask started telling us part of the history of this object. But it was by contrasting the object’s present condition with that recorded in earlier photographs that the tale of the object’s journey could start being pieced together.

Comparison with the earliest photograph, that taken by Thomas himself in 1911, allowed us to establish that the mask had already been repaired before it had been collected (see our earlier blog post about this) and that Thomas seems to have acquired it without the costume element of which we found traces. Put together, these two facts lend more weight to the likelihood that the mask had seen previous use rather than being especially made for Thomas. Indeed, in the 1911 photograph one can also see a coiled raffia bundle, which was probably placed on top of the wearer’s head as a cushionbefore putting the mask on.

A later photograph of the mask taken for the anthropologist G. I. Jones, for his book The Art of Eastern Nigeria, published in 1984, shows the mask free of some of the damage now visible. Specifically, the losses to the lip, and the breaks and subsequent repairs now visible on the jaw and on the four combs are not apparent in the photograph for Jones’ book. This gives us an approximate point in time after which this particular damage and the subsequent repairs must have happened: post 1984.

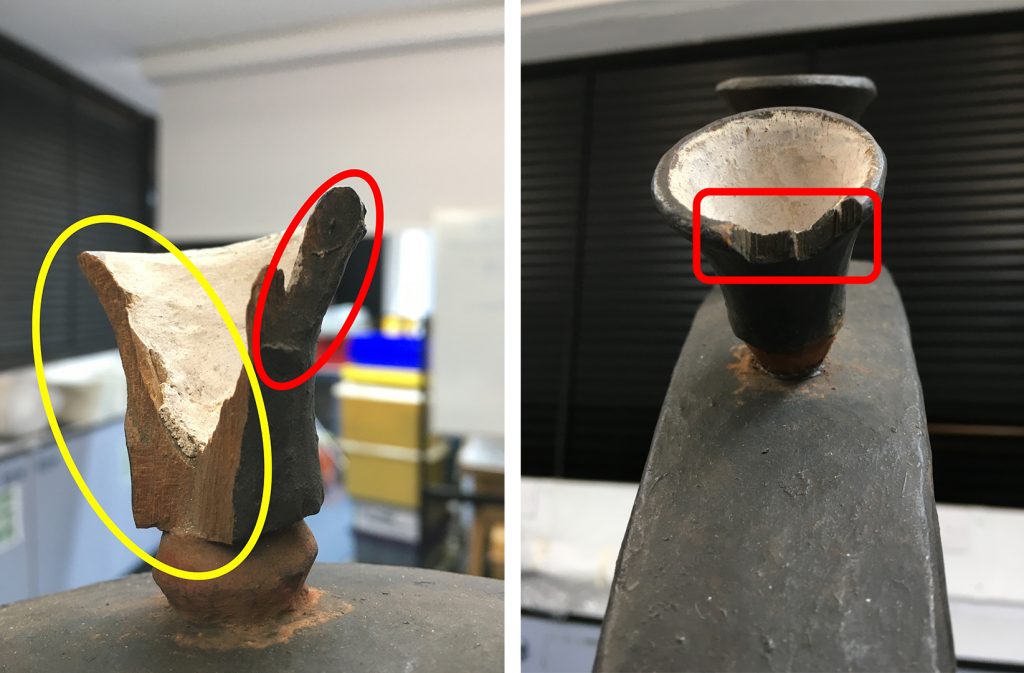

Repairs are particularly clear on the back of the front left comb and on the front and back right combs too, because the adhesive used has aged and darkened. The nature of the breaks and the similarity in the appearance of the adhesive used in the repairs suggests at least one episode of catastrophic damage – a fall, perhaps? – rather than gradual deterioration. Having worked on this object I have also experiential knowledge of its instability as the top heavy crest makes it prone to tipping forward.

All of the above has consequences for any future conservation of this mask: as the post-1984 repairs are relatively recent and carried out in the context of the museum, it may be acceptable to remove the darkened adhesive and redo the repairs should this become necessary. We would not consider doing this with the more historical repairs, which may instead be conserved themselves as a vital part of the object’s biography. Similarly, being able to date the more recent repairs to after 1984 may help identifying the adhesive used and the best approach to its removal. The option of redoing the recent repairs was not considered at this stage because the information only became clearer as we worked on the mask, but also because at present the repairs, although disfiguring, are stable and removing them now may cause unnecessary damage.

The hands-on conservation of the object started with cleaning. As with other objects collected by Northcote Thomas that we have treated as part of [Re:]Entanglements, there was much surface dirt, with dust and dirt accumulated in the crevices, recesses, and carved details of the mask. Some of this dirt was relatively easy to remove using standard museum vacuum techniques. However, on organic porous materials such as wood, if dust is left for a long time it can end up becoming engrained into the pores and harder to remove, giving the object a grey and dull look. This was definitely the case with the maiden spirit mask. So, first the loose dirt and dust were removed with a museum vacuum and soft brushes. This did not prove sufficient to remove the dull grey film of engrained dirt, and after testing the steadfastness of the various pigments, the mask was carefully swabbed with a solvent to help lift the dirt off its surface. This was quite successful and some of the original sheen of the surface was returned to the object.

The treatment then focused on the structural issues that were placing the mask at risk. There were cracks at the base of both the horns that attach the crest to the head. The crack to the front horn, in particular, seemed to go most of the way through and moved when handled. Both cracks were consolidated and secured by injecting a protein-based adhesive into the cracks with a syringe and holding them under tension in the correct position until the adhesive cured.

The stand which holds the bird on the right was very loose and unstable, and the historical repair there, which we discussed in an earlier blog post, no longer secured it. The iron metal sheet of the earlier repair also had a rusted surface and small losses to the bottom edge, as well as a nail missing, and even though the corrosion was not active, it was unsightly and was therefore cleaned off slightly. Flexible fills using Japanese tissue paper and a conservation grade adhesive were made under the metal sheet to pack the joint and secure the stand, and then tinted to match the colour of the mask in that area so that they would be largely invisible.

The surviving lip fragment was re-adhered and the old wooden mount has been temporarily raised with a layer of Plastazote foam, so as to lift the jaw off the ground and relieve the pressure exerted by the weight of the object on the jaw, which has resulted in cracks in the wood. A new mount will be made for the exhibition display to replace the existing one, which will definitively solve this problem.

Damage to the upturned bells on the top of the crest was also examined: two of the bells – the third and the fifth from the front – display losses. These do not present any risk to the stability of the object and therefore nothing was done other than cleaning. But a close examination of them tells of at least two episodes of damage. On the third bell some of the break edges are darkened and dirty, but there is also a cleaner and therefore relatively more recent break edge. Reference to the photographs showed that some of the damage to the third bell, corresponding to the darkened break edge, was there at the time Thomas photographed the object in 1911 and therefore predates acquisition. Further losses have evidently happened between the time Thomas photographed the mask and the date it was photographed for Jones’ book. The fifth bell also has a small loss to the rim, with a dark break edge suggesting an old break possibly contemporary with the earlier loss on the third bell, though the photographs do not show this area and so nothing can be said with certainty.

Throughout the conservation process, the mask gradually revealed more and more of its history, allowing us to speculate more confidently on how Thomas may have acquired it, guiding our conservation decisions, and helping us trace and even roughly date some of the damage episodes it has suffered after entering the collection. But it does not end here. As a result of this conservation treatment there is one more tale the object has started to tell us, and that could open another venue of information into this object’s past.

During the research carried out on Igbo maiden spirit masks as background for the conservation treatment, a very similar mask was located in the Art Institute in Chicago (Accession No. 1994.315). The mask in Chicago is described in Herbert Cole and Chike Aniakor’s book Igbo Arts: Community and Cosmos as being covered in an ‘encrusted patina’ and its polychrome surface may have been lost, but it is nevertheless recognisably similar and uses the same motifs as the mask collected by Thomas, suggesting that it was made by the same artist(s). It also appears to have the remains of the costume element. This discovery may open the door to further research into the provenance and origins of the mask collected by Thomas and the role it may have played in Igbo societies before it entered the collection, and is a clear example of the affordances conservation work offers within and outside its own remit.

As noted above, Thomas collected two maiden spirit masks in Agukwu Nri in 1911. The second one was recently included in a virtual ‘Museum Remix: Unheard‘ trail across the University of Cambridge’s museums. Senior Curator, Mark Elliot discusses some of the untold/unheard stories associated with the mask in this video.

Further reading

- H. Cole and C. Aniakor (1984) Igbo Arts: Community and Cosmos. Los Angeles: Museum of Cultural History, University of California.

- B. Hufbauer and B. Reed (2003) ‘Adamma: A Contemporary Igbo Maiden Spirit’, African Arts 36(3): 56-65 + 94-95.

- G. I. Jones (1984) The Art of Eastern Nigeria. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- N. W. Thomas (1913) Anthropological Report on the Ibo-Speaking peoples of Nigeria, Part I. London: Harrison & Co.