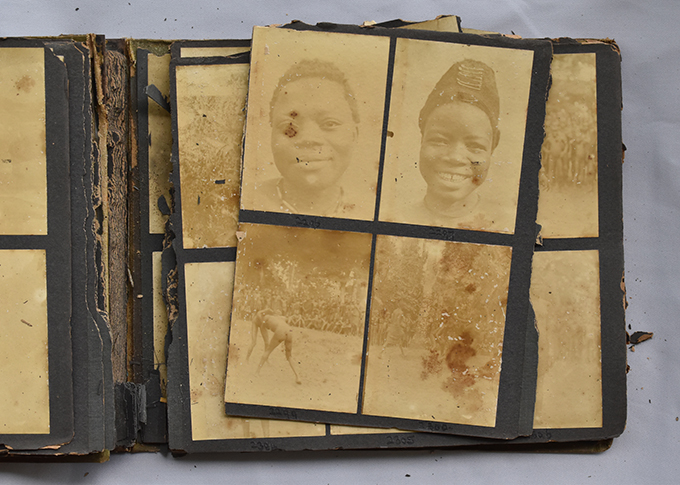

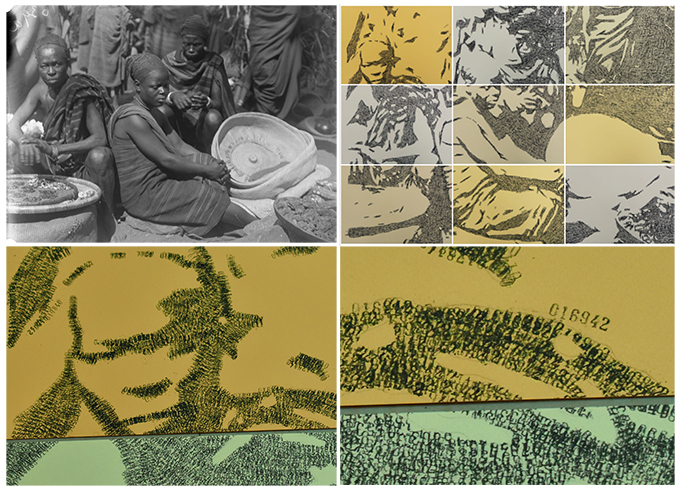

Over the last ten months, as part of our fieldwork for the [Re:]Entanglements project, we have been conducting research with 17 communities in present-day Anambra and Delta states in Nigeria. We have been revisiting locations that formed part of Northcote Thomas’s itineraries during his 1910-11 and 1912-13 anthropological surveys of Igbo-speaking peoples, equipped with copies of Thomas’s photographs, phonograph recordings and images of artefact collections.

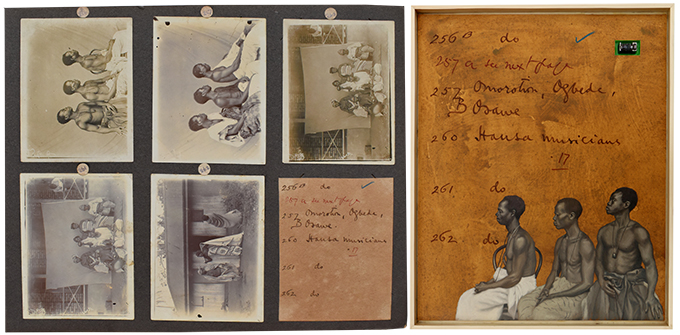

During our conversations and interviews with community members, and through setting up informal ‘pop-up’ exhibitions in these locations, Thomas’s photographs have elicited a wide spectrum of reactions, ranging from rejection and indifference to excitement, emotional connection, inquisitiveness, contestation and much more. In particular, we have been struck by how local people use their mobile phones to re-photograph the prints of Thomas’s photographs that we bring with us when visiting a community and how quickly these new digital copies circulate on WhatsApp, Facebook and other social media to extended family and community networks internationally.

Sometimes a single photograph can provoke especially strong responses, often because it touches on a ‘raw nerve’ or intervenes in contemporary issues, reminding us how history matters in the present. Thomas’s photograph no.4108 is one such case.

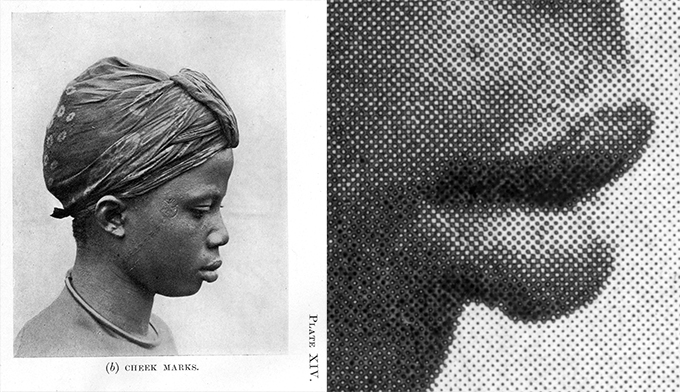

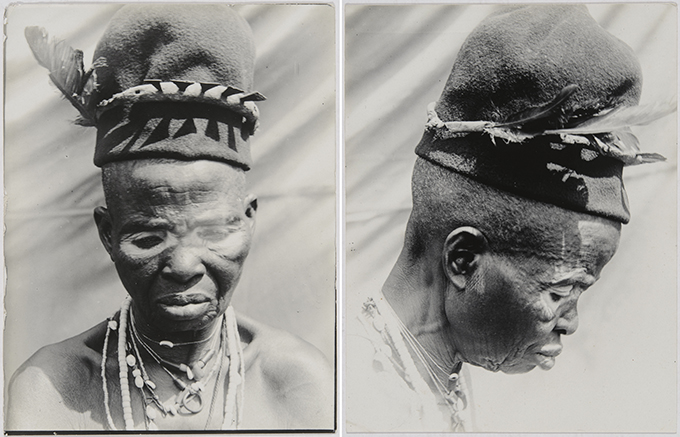

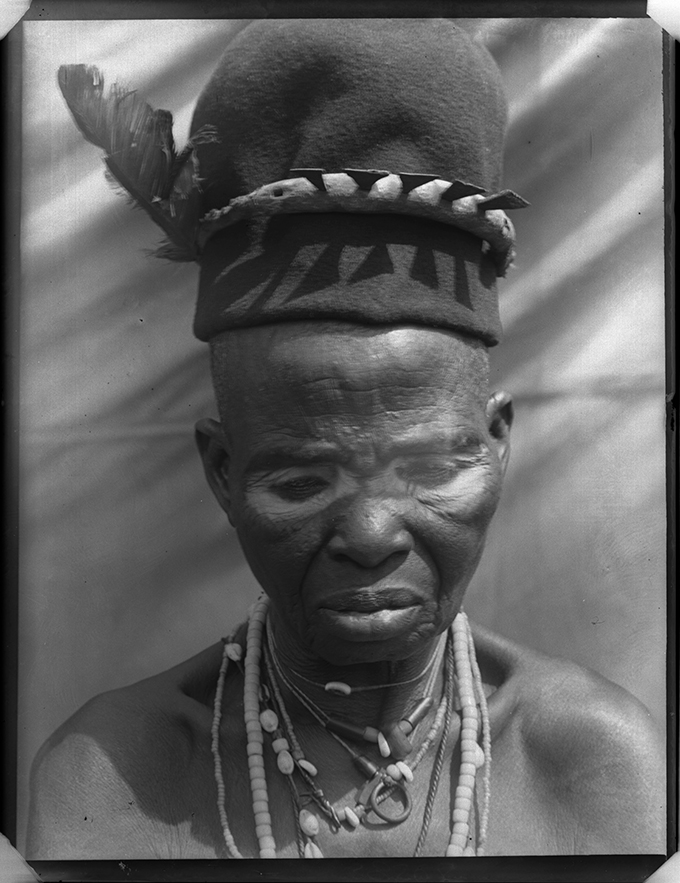

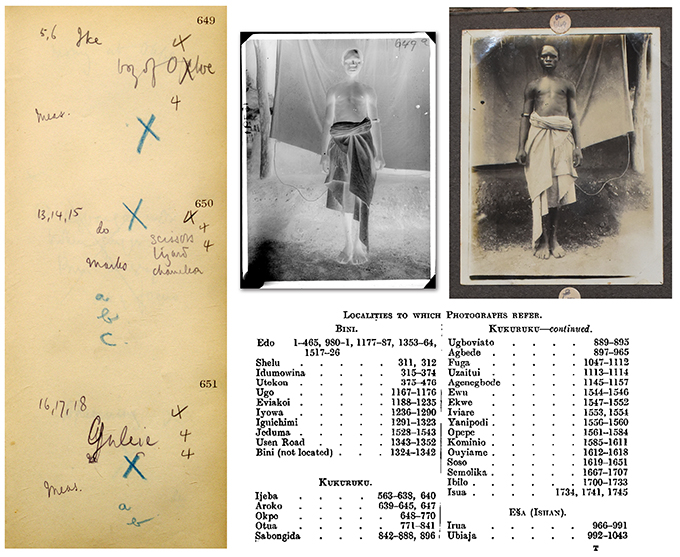

Photograph no.4108 is a portrait of a woman with white marks around her eyes and on her forehead created with nzu (kaolin chalk). Around her neck she wears an assortment of necklaces made from various beads and shells. On her head is a cap that has a band with a series of small triangular blades and feathers sticking out of it. According to the brief note in Thomas’s photo register, the subject of the photograph is the ‘Omu’ of Okpanam, in present-day Delta State, Nigeria.

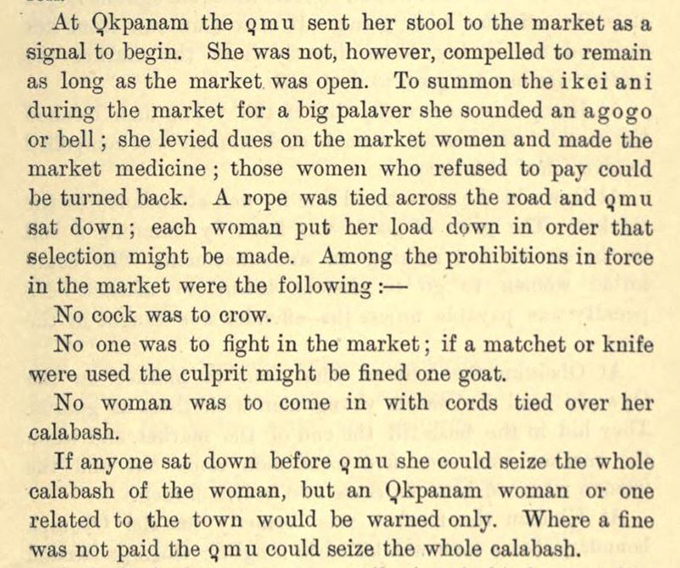

In volume four of his Anthropological Report on Ibo-speaking Peoples of Nigeria, Thomas gives some explanation of the role of the Omu in various communities in Anioma – the territory of the Igbo-speaking population West of the Niger River, which was the focus of Thomas’s 1912-13 tour. According to Report, Omu is the ‘market queen’, who presides over the market and serves the shrine in it. She enforces order, collects dues and controls the prices of goods for sale. In some places, Thomas records that the market cannot begin until the Omu arrives, and that she may fine the women of her town for non-attendance and forbid them to go to more distant markets instead of attending that in their own town. At Okpanam, Thomas tells us that the Omu sent her stool to the market as a sign for it to begin.

Northcote Thomas made around 30 photographs in Okpanam, many recording the title-taking ceremony of Obi Mgbeze that was happening when he visited in September 1912. However, during our fieldwork in Okpanam, it was the photograph of the Omu that consistently attracted most attention and elicited the most comment.

As Thomas’ photograph of the Omu was viewed and re-photographed, the recurring comment it produced was: Okwa ha si na Omu adi ekpu okpu ododo? (‘Why do people argue that the Omu does not wear a red cap?’) The comment indexes an ongoing contestation about the right to wear the red cap in the community.

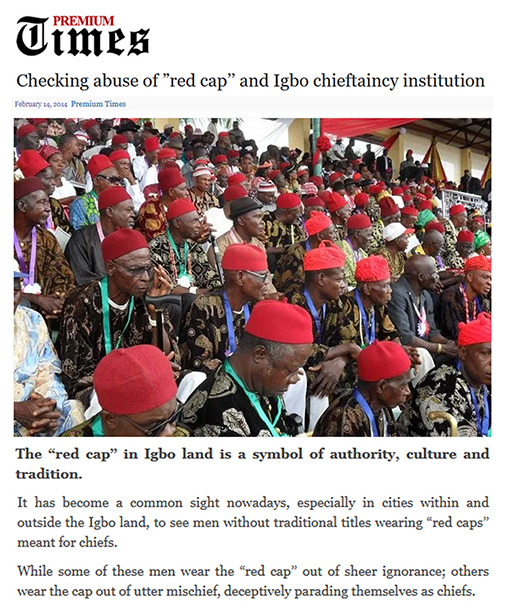

During colonial times in Igbo-speaking areas of Nigeria, the red cap became part of the regalia of office for senior title holders, including the so-called ‘Red Cap Chiefs’ or warrant chiefs. More recently, concern has been expressed that this symbol of authority is being worn by those who have no right to wear it.

In Okpanam the issue of the okpu ododo or red cap has become entangled in local political disputes. Traditionally, Okpanam’s community was headed by the Diokpa-Isi, the eldest man in the community. As the administrative demands on the Diokpa-Isi grew, and considering his old age, members of Okpanam community at home and in the diaspora agreed to institute the new post of Ugoani. The process, which began in 2004 and was approved by Delta State government in 2009, was followed by the election of Dr Michael Mbanefo Ogbolu as Ugoani in May 2010. Following the performance of the associated rite in 2011, he was given staff of office by the government. The Ugoani was intended to act as the representative of the Diokpa-Isi and Izu Ani (General Assembly), but remain answerable to them. Over the past few years, however the Ugoani and his council have assumed greater power, such that the Ugoani has come to be recognized as the modern political head of Okpanam by the State, while the Diokpa-Isi, Izu Ani, Obi titled men and Omu have become regarded as ‘traditional’ roles. This has led to tensions and the red cap has become a symbol of the squabble.

Against the custom of the community, which stipulates that only Obi title holders and the Omu (whose status is equivalent to that of an Obi) are eligible to wear the red cap, the Ugoani and his cabinet members began to incorporate the red cap into their regalia, even though they do not hold the Obi title. The Obis then sued the Ugoani and his council, demanding that they stop wearing the red cap. As the contestations escalated, both sides issued statements and counter-statements in the Nigerian press and in various online forums. Responses of the Ugoani and Ugoani-in-Council were reported in The Nigerian Voice, for example, stating that the Omu is only a chief (albeit a ‘respected and revered one’), not of equivalent status as an Obi, and is therefore not entitled to wear the red cap either.

These statements were refuted strongly by Obi title holders in Okpanam, who drew attention to the ancient institution of the Omu compared to the recent establishment of the Ugoani role. In a lengthy post to the Anioma Trust Facebook page, Obi Nwaokobia was reported as stating that the ‘Ugoani has no authority to make a statement on Omu Okpanam’. Obi Nwaokobia further explained that ‘the institution of Omu has existed [since] the founding of Okpanam’ and that she is ‘the Traditional Mother of the community and she enjoys all the rights and privileges of a Royal Mother’. When an Omu dies, like Obis, she is buried in a sitting position, and in Okpanam, the Omu is more than a chief but in the same rank as Obis.

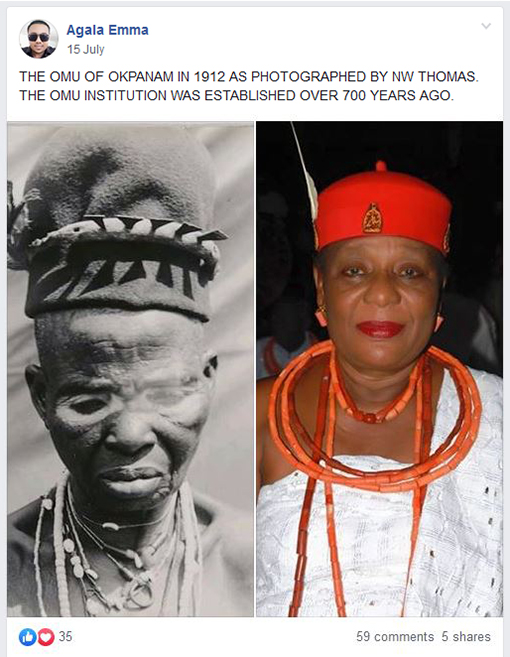

When we came to Okpanam, we were not aware of the contestation around the Omu’s status or her right to wear the red cap. When we learnt of the controversy, however, it was not surprising to find that the Thomas’s photograph of the Omu in 1912 elicited such a powerful response. Although the photographs are monochrome, the style of the hat with its band and feathers is clear. Here was irrefutable evidence that the Omu traditionally wore the red cap.

For many, the ‘red cap controversy’ has been settled by an archival image. Photographs of Thomas’s photograph soon began circulating on social media after our visit, bringing it to the attention of the international Anioma community. At the ‘Okpanam Indigene’ Facebook page, for example, Emma Agala juxtaposed Thomas’s 1912 photograph with that of the current Omu, HRM Obi Martha Dunkwu, and included a long extract from Thomas’s Anthropological Report on the role of the Omu. The extensive research of the [Re:]Entanglements project itself was cited as confirming its authenticity. Among the 59 comments to the post, Martha Dunkwu herself remarks: ‘You are right. The red cap is there, the feather, the beads, the Akwa Ocha. Did you notice that the Aziza [that] the male Obis use is on her red cap? It’s wonderful that the British in 1912 recorded Omu-ship in Okpanam’.

No doubt the debates will continue in Okpanam, but the incident demonstrates how the ethnographic archive may intervene in contemporary events in ways that we have not anticipated. Our fieldwork following Northcote Thomas’s itineraries in West Africa can present many challenges, but the story of Omu and her red cap reminds us of the importance of bringing back this archive to the communities whose histories it documents.

![Scenes from opening of [Re:]Entanglements exhibition, National Museum, Lagos](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/National_Museum_Lagos_exhibition_opening_re-entanglements.net_.jpg)

![[Re:]Entanglements exhibition view, National Museum, Lagos](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/National_Museum_Lagos_exhibition_view_re-entanglements.net_.jpg)

![[Re:]Entanglements exhibition view, National Museum, Lagos](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/National_Museum_Lagos_exhibition_view_2_re-entanglements.net_.jpg)