Video of a presentation about the [Re:]Entanglements project by Paul Basu at the Igbo Conference, held at SOAS University of London, 21 April 2018.

Month: July 2018

Rediscovering Northcote Thomas’s artefact collections

Over the coming months, we shall be exploring the artefact collections assembled by Northcote Thomas during his anthropological survey work in Nigeria and Sierra Leone between 1909 and 1915. The collection of ‘ethnological specimens’ was very much a part of anthropological fieldwork in the early twentieth century, and part of a broader project of ‘salvaging’ what was perceived to be the last vestiges of ‘primitive society’ before they were made extinct by the incursion of colonial ‘civilization’. Thomas had written about the need for making such collections long before he conducted any fieldwork himself and, in 1909, he echoed his earlier sentiments when justifying his collecting activities to the Colonial Office: ‘I regard the making of these collections as important. … The opportunities which I have may not recur, every year European goods are ousting native products more & more’.

Judging from correspondence with C. H. Read and T. A. Joyce at the British Museum, it appears that Thomas purchased most of the objects he collected at markets or else commissioned them to be made. This is in stark contrast with the looting of antiquities and treasures that accompanied colonial campaigns, such as the notorious Punitive Expedition to Benin City in 1897. Thomas initially anticipated that the collections would be acquired by the British Museum. However, Read, who was then Keeper of Ethnological Collections, declined the collections from his 1909-10 tour, partly due to a misunderstanding about funds available, partly because Thomas insisted that the collection be kept together in its entirety, but partly also because many of the objects were indeed made especially for Thomas. As Read wrote, ‘I am by no means sure that I want these modern things made to order as it were’. Today, paradoxically, Thomas’s collecting methods would be considered highly ethical.

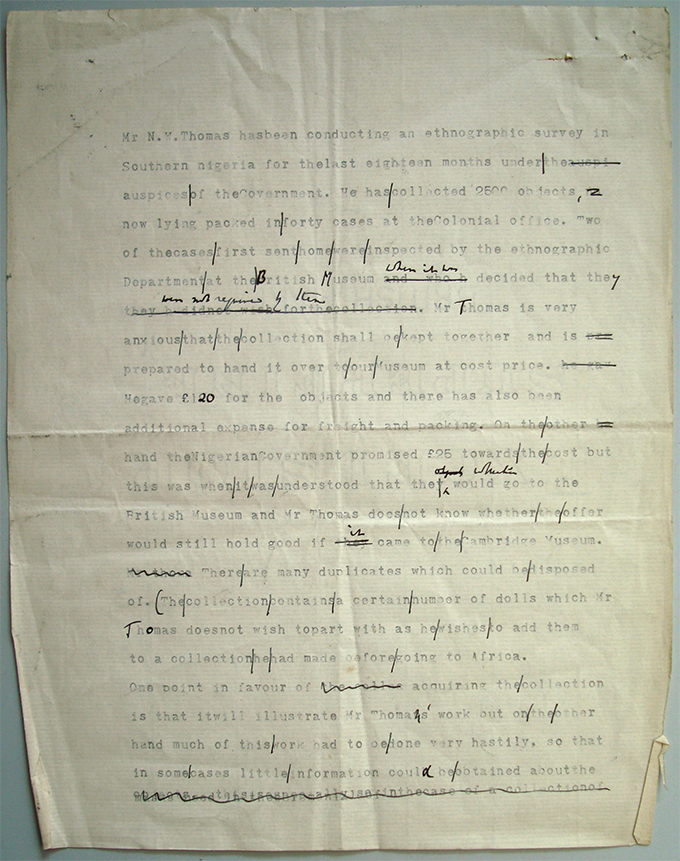

Thomas subsequently offered the collection to the University of Cambridge’s Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology. A draft letter by the museum’s curator, Anatole von Hügel, to the University’s Antiquarian Committee, which was responsible for the museum, survives in which he recommends acquiring the collection. Von Hügel notes that there are some ‘2500 objects, now lying in forty cases at the Colonial Office’, and ‘Mr Thomas is very anxious that the collection shall be kept together and is prepared to hand it over to our Museum at cost price’. He adds that ‘Mr Thomas procured what he believes to be the last examples of genuine native workmanship in many villages’. The sum of £100 was raised from one of the Museum’s regular patrons, Professor Anthony Bevan of Trinity College Cambridge, and the collection was duly acquired.

Having acquired the collection he assembled during his first tour in Edo-speaking areas of Southern Nigeria, Thomas was then given a grant by the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology ‘for collecting purposes’ during his subsequent tours among Igbo-speaking communities (1910-11, 1912-13), and it appears that Thomas donated the collections he assembled in Sierra Leone (1914-15). Together the ‘Thomas Collection’, as it was known, provided a comprehensive representation of ‘native manufactures’ of Southern Nigeria and Sierra Leone. The size of the collection was such that the gallery in which they were stored at the Museum was assigned as a dedicated ‘African room’.

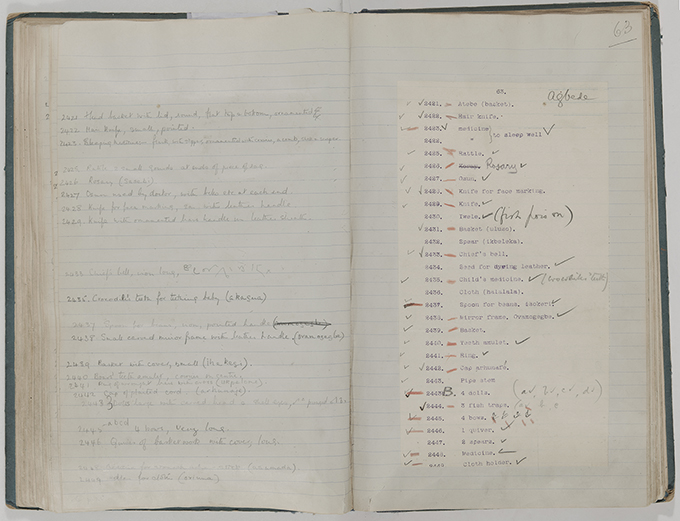

Documenting and caring for a collection of this scale also presented challenges, especially since a large number of the objects had been damaged in transit from West Africa to Britain. The Museum’s Annual Reports in the years following the initial acquisition often mention the work of ‘cleaning, mending and restoring’ the objects; while Thomas himself assisted in the work of classifying and labelling the collections. Indeed, the work of accessioning, cataloguing and documenting the collection has continued sporadically over the decades. This work was carried out by individuals who went on to become established figures in the study of African Art, including G. I. Jones in the late 1940s and Malcolm Mcleod in the early 1970s. In the late 1980s, a project was led by Cambridge students, Roger Blench and Mark Alexander, to re-examine the collections, and today, of course, we are engaging with them again in the [Re:]Entanglements project.

Thomas photographed some of the objects he collected ‘in the field’, prior to having them packed in crates and shipped to Britain. Our starting point as we work through the collections is to identify and locate these same objects in the Museum stores, to photograph them in detail, and to enhance the Museum’s catalogue record of each. You can follow our progress by joining the project’s Facebook Group, and, indeed, you can make your own discoveries by searching the MAA’s online catalogue.

Panoramic photography and photographic excess

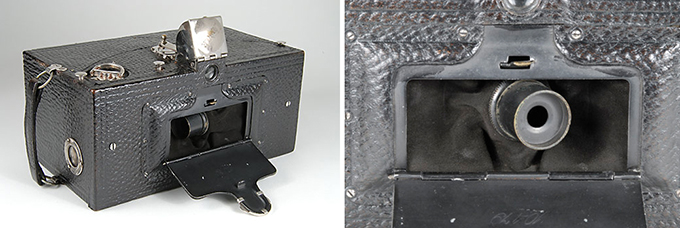

Northcote Thomas used a number of different cameras during his four anthropological surveys in West Africa between 1909 and 1915. During his first tour, in Edo-speaking areas of Nigeria, his equipment list included a Hunter & Sands Tropical camera and a Goerz camera. On his three subsequent tours, in Igbo-speaking areas of Nigeria and in Sierra Leone, however, his photographic kit included three cameras: an Adams Videx camera, a Stereoscopic camera, and a Kodak Panoram camera. The majority of Thomas’s photographs were taken on quarter plate glass negatives on the Videx, but it is clear that Thomas experimented with both stereoscopic photography, also using quarter plates, and panoramic shots using the Kodak Panoram, which used 105 format roll film.

Through the [Re:]Entanglements project, we have been systematically digitising all of N. W. Thomas’s photographic negatives and prints with our partners at the Royal Anthropological Institute and University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology. Until recently, we believed that only Thomas’s quarter plate glass negatives and corresponding prints had survived. However, we were excited to discover quite a number of his panoramic prints in the collections in the Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology. On a recent research visit to the National Museum in Lagos, Nigeria, we were also delighted to find a number of these panoramic prints mounted in one of the photograph albums produced during Thomas’s surveys.

The Kodak No.1 Panoram camera, which Thomas used, was manufactured between 1900 and 1926. The camera had a swinging lens, which took 3.5 x 12 inch exposures across a 112 degree arc on 105 film stock. An advertisement of the time asserts that ‘The pictures taken by these instruments have a breadth and beauty not attainable with the ordinary camera. The wide scope of view makes the Panoram excellent for taking landscapes, as it can cover a wide area without the distortion incident to the use of wide angle lenses’. There is an excellent article on the Kodak No.1 Panoram at Mike Eckman Dot Com.

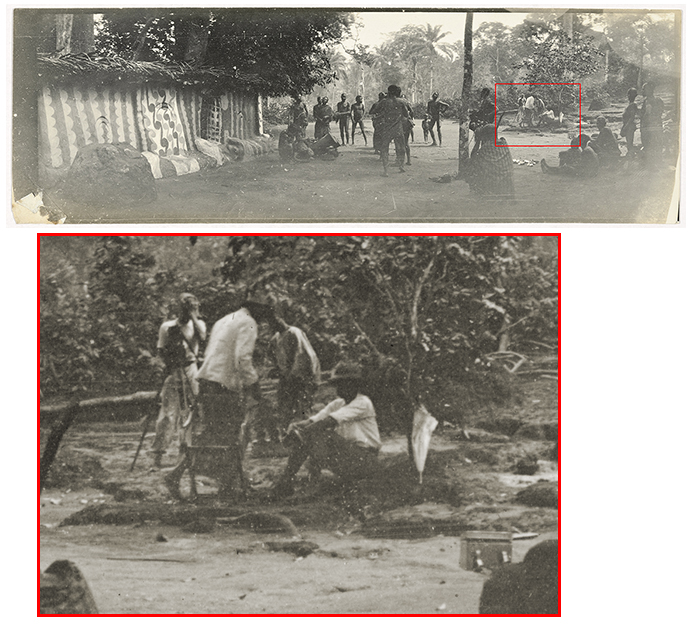

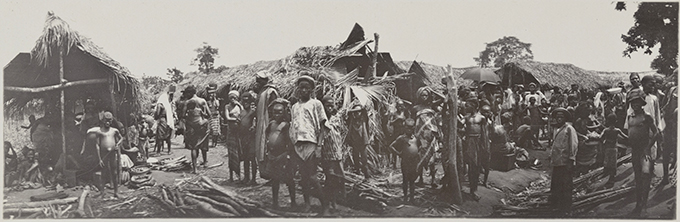

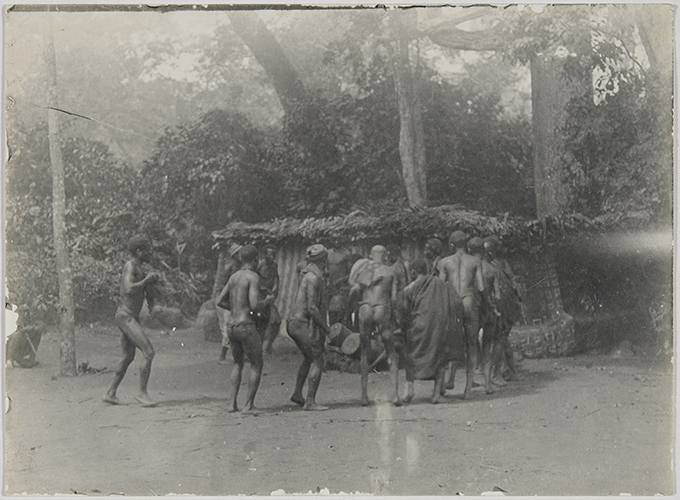

The more we explore Northcote Thomas’s fieldwork photography, the more we learn how innovative he was for the time. For example, during his 1910-11 tour in what was then Awka District, he experimented with using two cameras simultaneously to photograph a scene from different angles. This technique would, of course, become an important technique in cinematography. (The earliest known example of a two-camera set up in cinema was the 1911 Russian film Defence of Sevastopol.) In the example here, we can see that Thomas and his assistants simultaneously photographed what is described as the Ogugu ceremony at Agulu, south of Awka, using both the Adams Videx and Kodak Panoram cameras.

In the resultant sequences of photographs there is a further intrigue, which speaks of the ‘excess’ of the photographic image, and particularly the peripheral presences that creep into the frame without the photographer’s awareness. Of over 7,000 photographs in the archive, there are perhaps only three or four that intentionally show something of the process of Thomas’s anthropological survey work. It is only through this photographic excess that we catch glimpses of the endeavor.

To date, then, the only photographs we have seen in which we glimpse Northcote Thomas behind the camera are the reverse shots of the Ogugu ceremony at Agulu taken by one of his assistants on the Kodak Panoram. In the background of the panoramic shot we see Thomas stood behind the tripod mopping his brow together with three of his assistants and items of his kit strewn around. A rare insight into the anthropologist-photographer at work.