Among the many collaborations involved in the [Re:]Entanglements project is a partnership with the Museum Conservation programme at UCL’s Institute of Archaeology. Under the supervision of Drs Dean Sully and Carmen Vida, students on the graduate programme have been working on a selection of objects collected by Northcote Thomas during his anthropological surveys of Nigeria and Sierra Leone. Project coordinator, Carmen Vida, introduces some of the contributions of conservation in this the first in a series of posts from the UCL Conservation team.

Starting in February 2019, as part of the [Re:]Entanglements project, a selection of objects belonging to the N. W. Thomas Collection at the University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (MAA) have come to UCL’s Institute of Archaeology for conservation. The project is allowing us to interact with the collection in new ways and to approach, explore and elicit some of the past and present meanings of the archive Thomas put together. As a result, in many cases the objects in the stores are being studied for the first time and the cobwebs are being dusted off, sometimes quite literally.

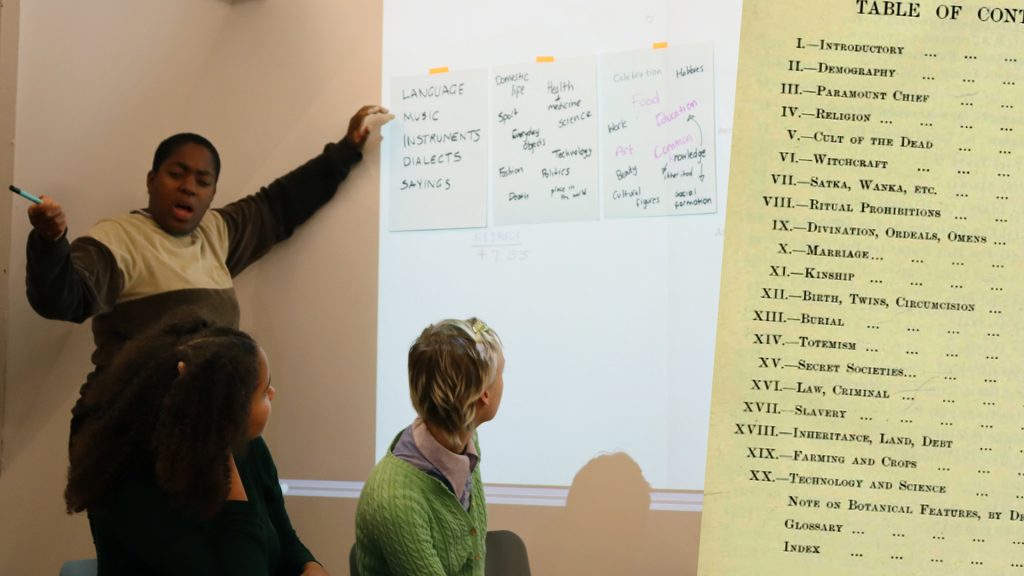

Conservation has a particular role in the [Re:]Entanglements project: not only does it ensure that the objects are stable enough to be used by anyone interacting with them, but as a distinct form of engagement, it provides intimate knowledge of the objects and can shed light on their make-up and their biography. Due to the lack of contextualising documentary evidence, museum objects often appear to be ‘mute’. But even where there is documentary evidence, the histories and narratives that have reached us provide one side – often someone’s side – of the story. Conservation can help provide a voice to the objects themselves, which may sometimes corroborate, but at other times question, the established histories associated with the objects. In doing so, conservation affords present day audiences the possibility to re-engage with the objects, whilst exploring the way in which the archive came to be both from past and contemporary perspectives.

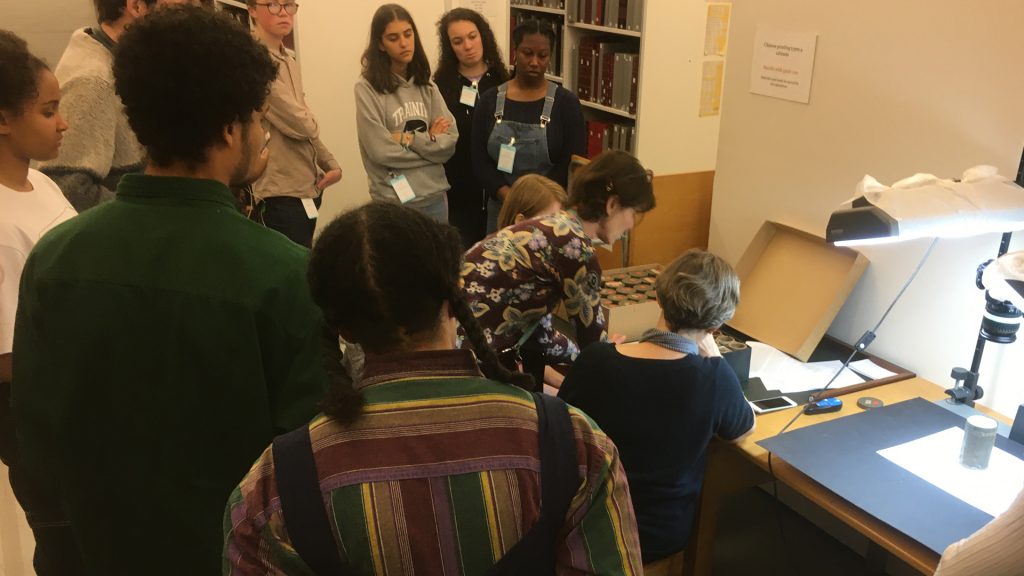

By the time the project is finished more than 40 objects will have been worked on at the Institute of Archaeology’s conservation lab and at the MAA. The objects being treated vary in type and size, and are but a small part of the N. W. Thomas Collection, which includes over 3,000 objects. Some will form part of the [Re:]Entanglements exhibition due to open in Cambridge in April 2021, whilst others are being conserved because, after over a century of existence, they have become unstable even when packaged away in a museum store. The work is being carried out both by professional conservators and students, and is allowing these students to develop their skills and further their training, another affordance of the project. We are also providing running some workshops for the Art Assassins, the youth forum of the South London Gallery, which is another collaboration within the [Re:]Entanglements project.

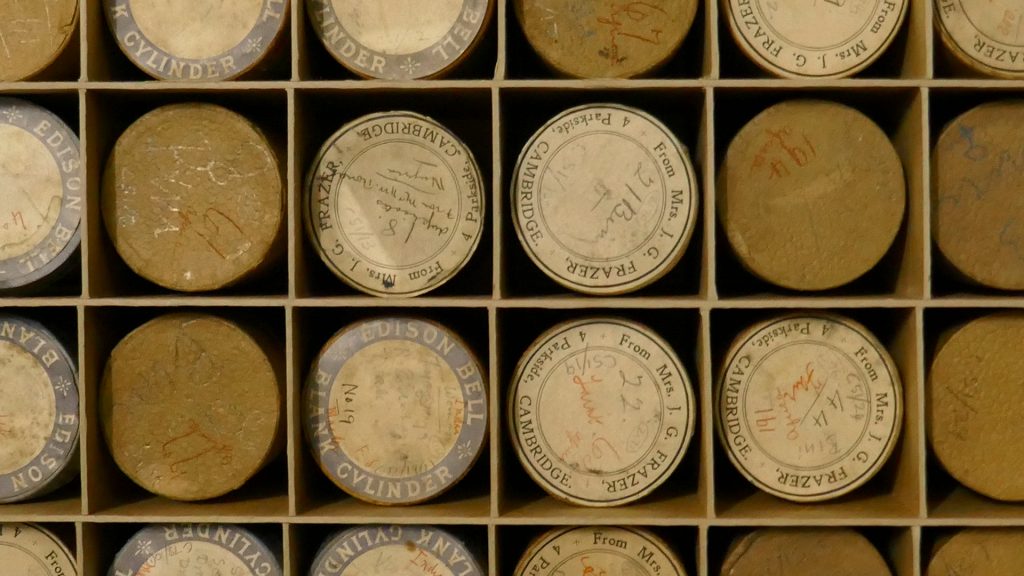

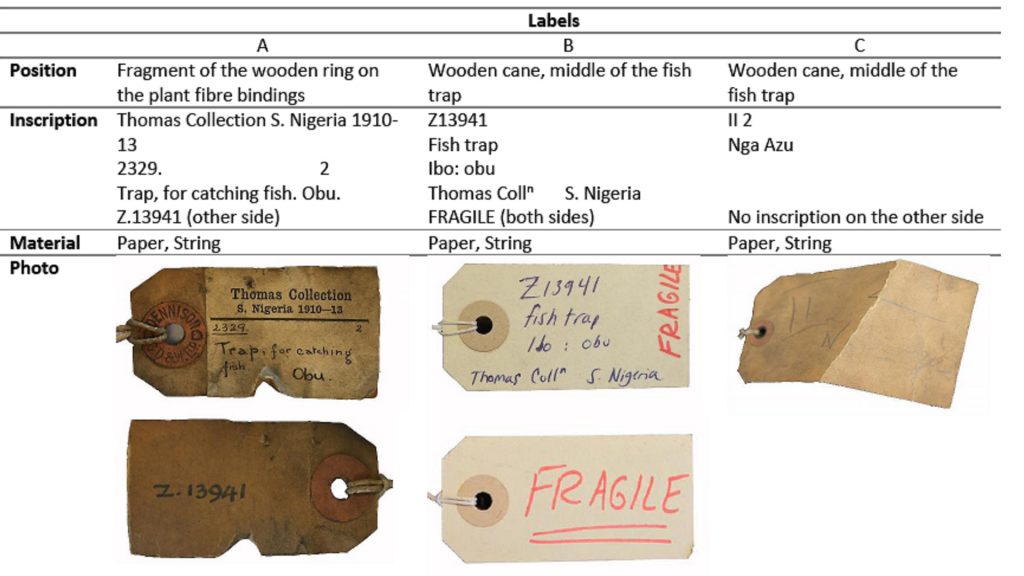

There is a whole array of tools and techniques that we use in conservation to better understand the objects and inform our treatments. Documentation is essential, starting with any existing historical information to which we can correlate the object itself: documents, photographs, previous museum information in the form of labels or markings on the objects. Labels are interesting things: sometimes informative, sometimes deceptive and indicative of misidentification at some stage. Our conservation work on the N. W. Thomas Collection includes the preservation of labels and museum numbers marked on the object, as they have by now become part of it and of its history.

Visual analysis of the objects can be extremely revealing for a trained eye. We use microscopes to examine the surface of the objects, looking for evidence of damage and instability, but also for clues as to the history of the object: manufacture materials and techniques, damage and/or repairs (whether before or after collection), evidence of rituals or of use are all things we will be looking for in our work. All these tell stories and give the object a new voice. Some of the objects treated so far exhibit extensive pest damage, and microscopy has helped us find evidence of the pests themselves, which will be later used by expert entomologists to identify the species and give us a good idea of where the damage might have occurred. The insect damage in some of the objects reflects their places of origin in West Africa (termites) as well as their later history (wood boring insects that can be found in the UK).

But conservators do not rely on visual inspection alone and we are trained to use most of our senses as part of our work, not just our eyes and hands. Smell, for instance, can help us identify fungal infestation, or certain materials used in the past. And by listening to the sound when we very gently tap a surface, we can ascertain the extent to which it may be hollow under the surface as a result of pest activity. One sense we are definitely not encouraged to use is taste! – not least because of the toxic materials earlier conservators may have used to treat objects.

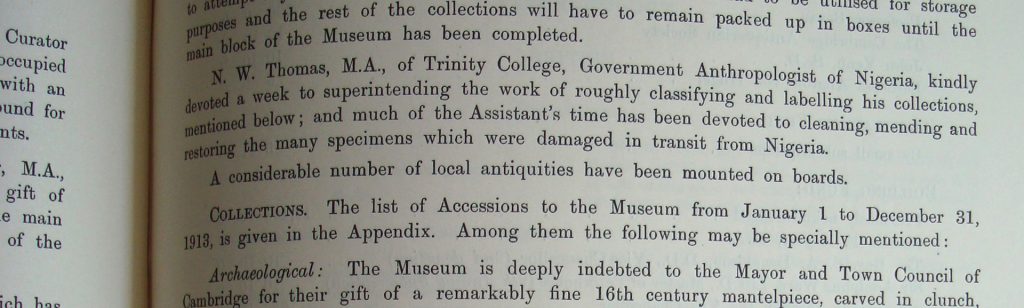

Other techniques we use help us to identify materials whether original or introduced by repairs done in the past. Ultraviolet fluorescence, for instance, can reveal the presence of modern adhesives and materials in objects. Chemical tests can help identify binders and pigments used in their decoration. Elemental analysis with portable technology such as p-XRF (portable X ray fluorescence, which detects inorganic elements such as metals and minerals) can help us identify not just what the objects are made of, but also, for instance, if they were treated with pest treatments no longer used such as arsenic or mercury salts. And we can use Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) to identify organic compounds. In this way we were able to establish, for instance, that a white deposit on one of the masks (Z 13728) was paraffin wax. This identification helped us both clean it safely by using the right solvents, but also to speculate that the mask may have received some treatment, possibly soon after arrival at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge. Paraffin wax was often used as a filler and protective coating treatment for wooden objects from the end of the 19th century and into the first half of the 20th century. In this case, our findings support documentary evidence from the museum’s Annual Reports in the years shortly after acquisition that the objects were cleaned, mended and restored.

Our work so far has also allowed us to interrogate and qualify some of the other knowledge resulting from the [Re:]Entanglements project’s collections-based research. Thomas’s correspondence, for instance, indicates that – in stark contrast to the current practice in his time – he commissioned some of the objects he collected to be made or else bought them at markets. One of the objects conserved at UCL in 2019 is an Igbo maiden spirit mask. The initial visual examination of the mask identified a number of historical repairs, including an iron sheet stabilising one of the bird figure on the proper right of the headdress, an iron staple across a crack on the proper left side of the headdress, and a plant fibre tie on the same area as the staple but further down. In the case of the iron staple and the fibre ties, they are covered with the same pigment used on the rest of the mask, suggesting they are original repairs. Checking the current condition against Thomas’s field photographs showed that the iron sheet repair securing the bird was already there when the mask was photographed by Thomas, presumably at the time of acquisition. These repairs could both be indicative of use prior to collection, in which case the mask would had had a previous life and not been simply commissioned by Thomas, or else be repairs carried out during the process of manufacture, not an uncommon occurrence. Currently we have not been able to resolve the matter of previous use in relation to this object, but nevertheless this conservation work has raised the question, allowing us to continue looking for evidence of previous use in other objects. That is one of the research questions we will be looking to find evidence for when treating other objects.

To date, nine objects have received treatment, and conservation of the remaining objects is underway. In this and subsequent conservation-themed blogs we will be sharing some of the stories that are coming to light as a result of the conservation work.

As noted above, many of the objects undergoing conservation and being discussed in this series of posts will be exhibited at the [Re:]Entanglements exhibition at the University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology due to open in April 2021.