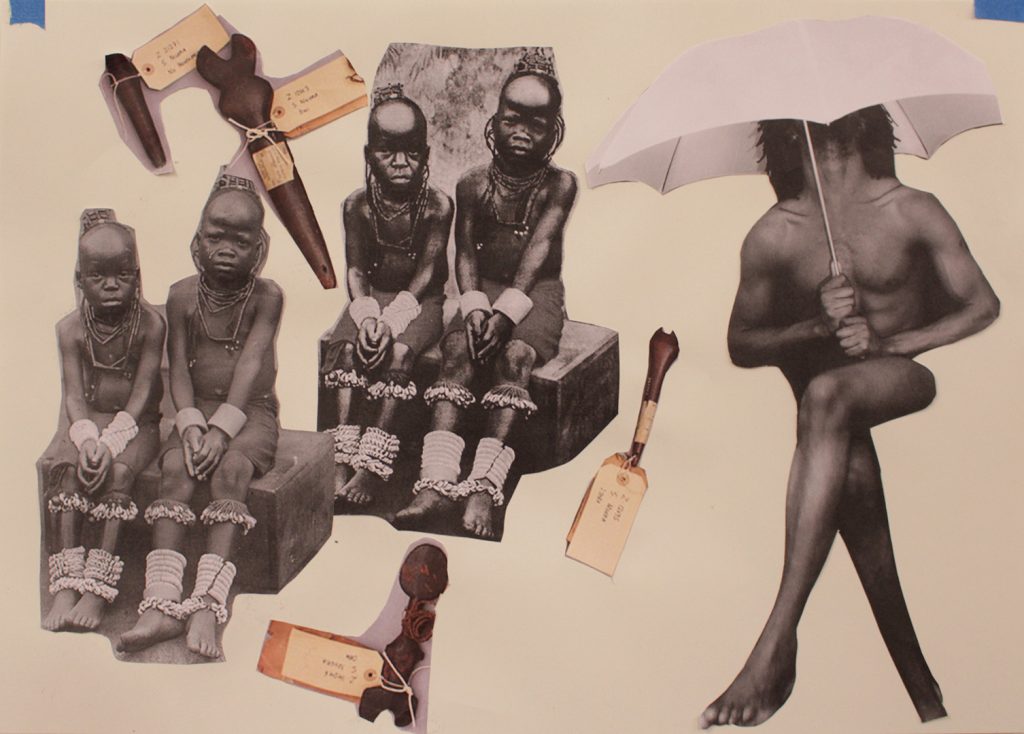

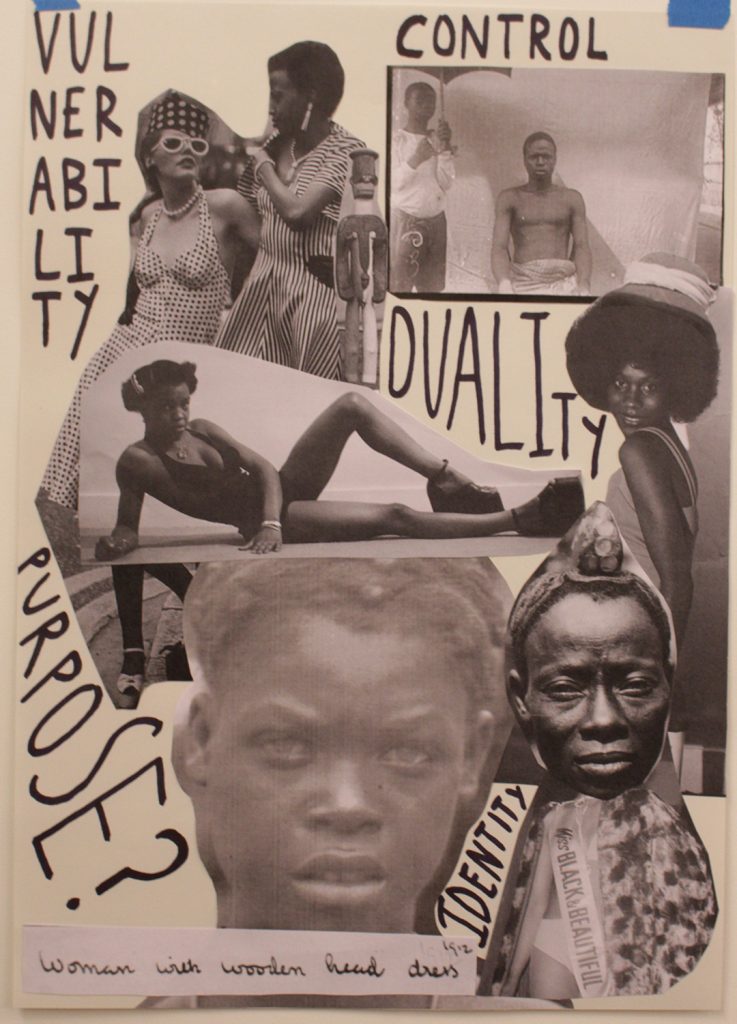

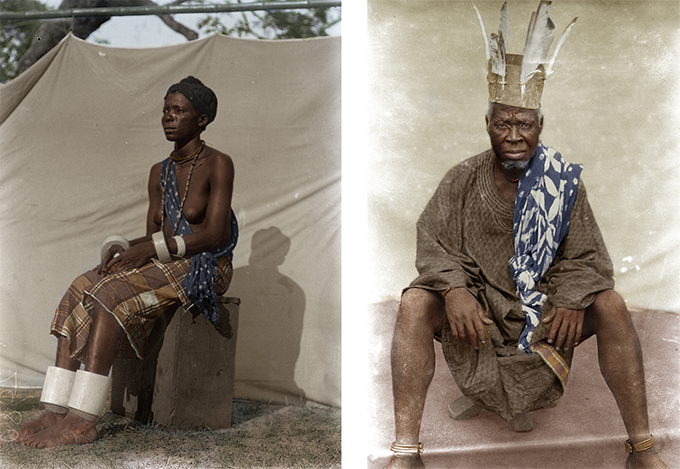

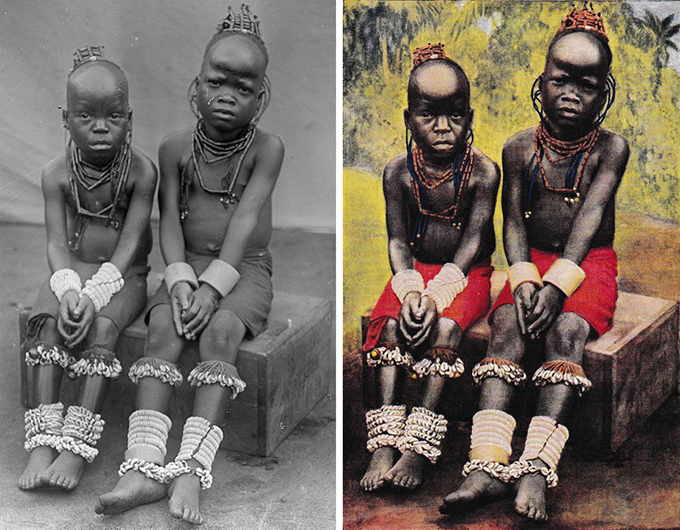

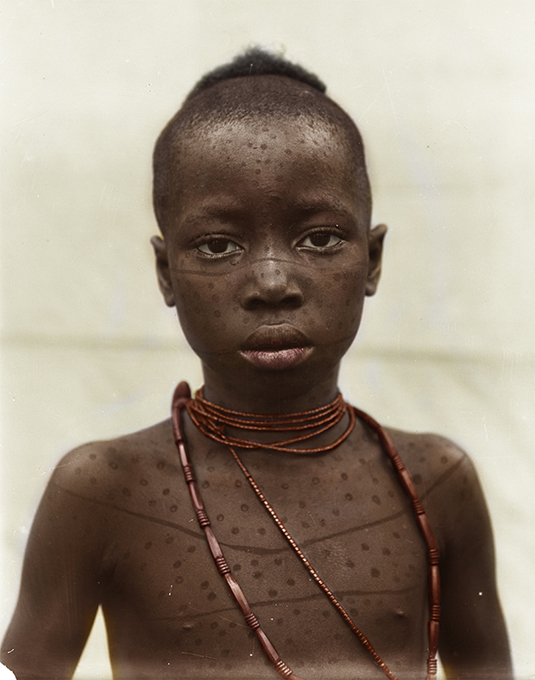

The histories of anthropology, photography and colonialism are entangled. Of the various genres of anthropological photography, the ‘physical type’ portrait epitomises the colonial anthropological gaze most fully.

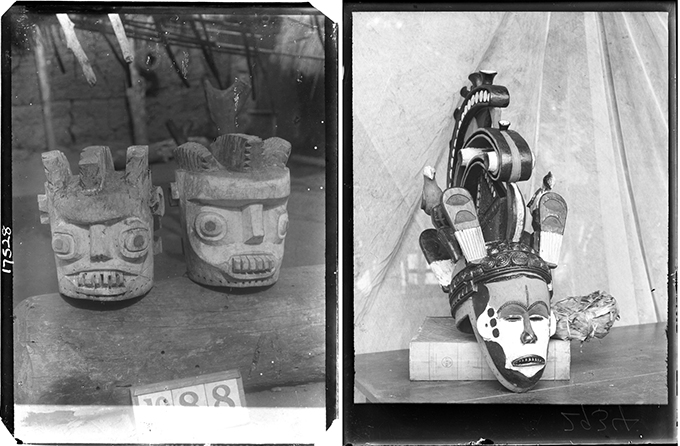

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the discipline of anthropology embraced not only the study of human social and cultural practices, but also the anatomical and physiological dimensions of human beings as a species – a field known as physical anthropology.

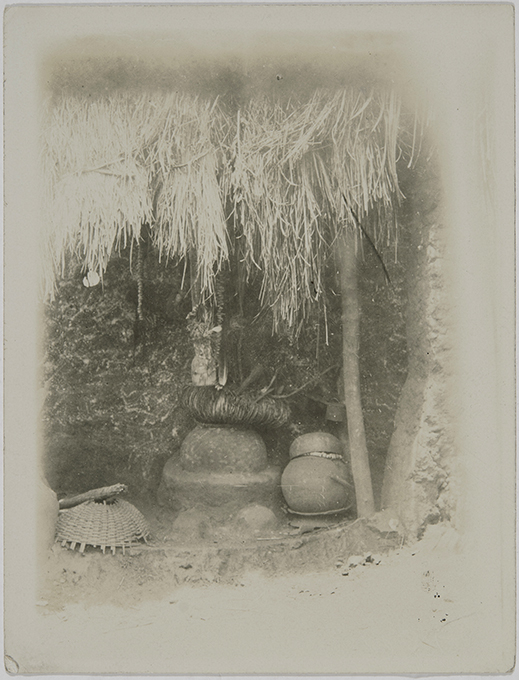

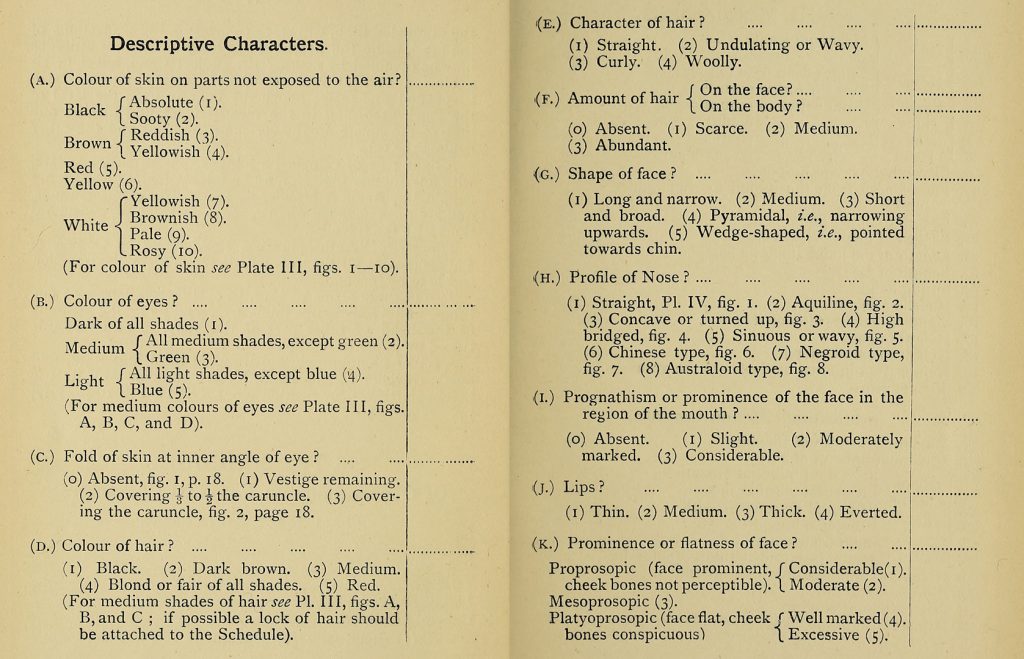

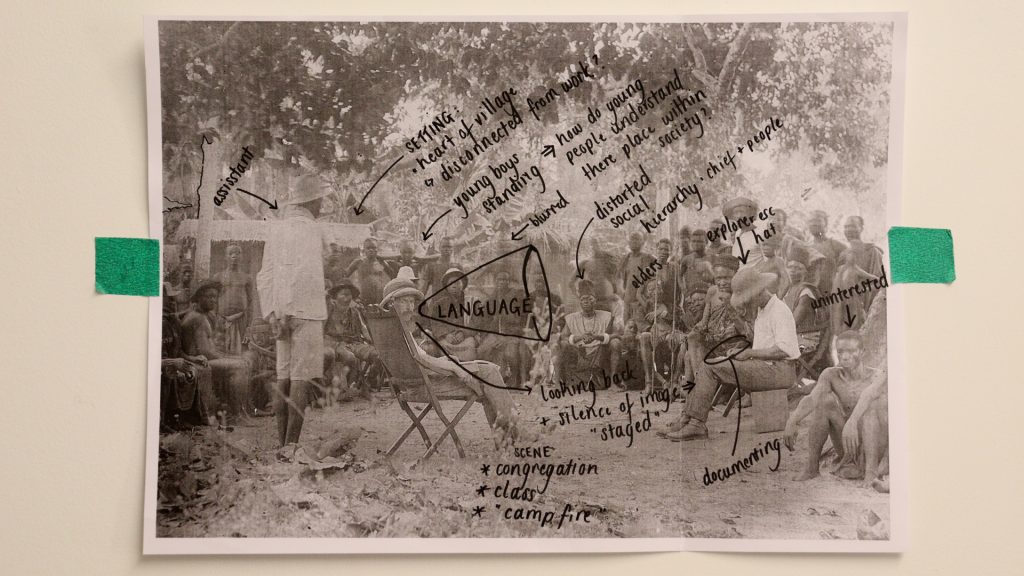

Anthropologists were interested in recording the physical characteristics of different population groups. As set out in Notes and Queries on Anthropology, the indispensable guide to anthropological fieldwork of the era, this included everything from documenting the colour of skin, eyes and hair to describing the shape of the face, nose and lips, as well as making anthropometric measurements of the body.

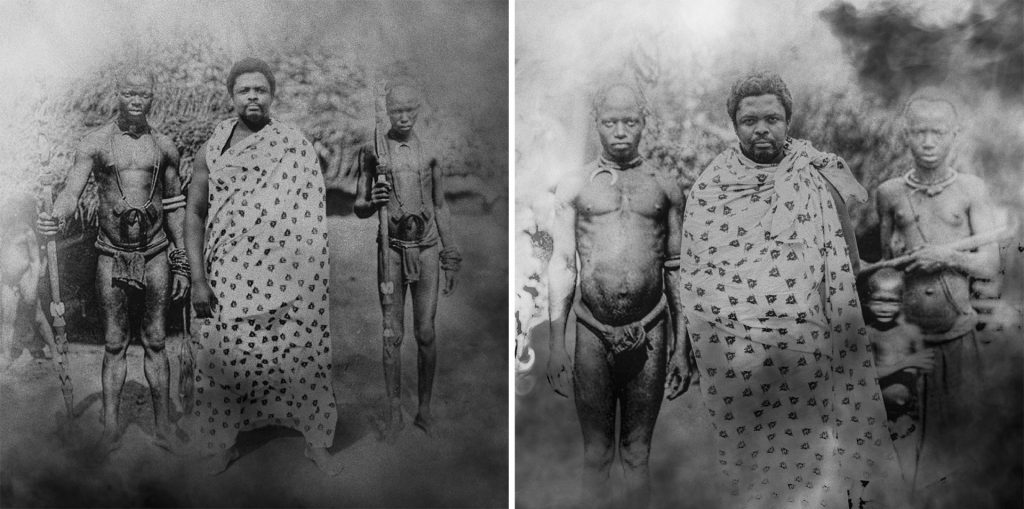

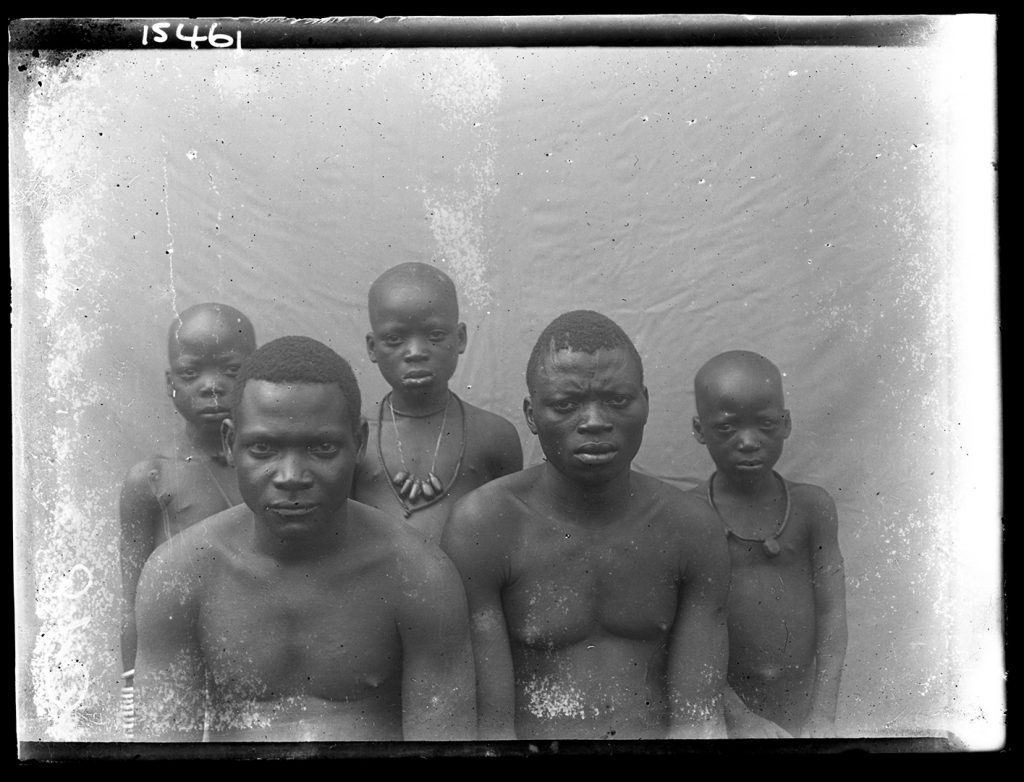

Through this documentation of human anatomy, anthropologists sought to identify the physical characteristics of what they perceived to be distinct racial and tribal ‘types’. Population groups were compared and categorised according to these typologies, much as natural scientists classified animal and plant species according to taxonomic conventions. Correlations were made between perceived biological differences and the distinct cultural and linguistic differences between groups, and these were placed in evolutionary schemata from the most ‘primitive’ to the most ‘civilised’.

All this would, of course, be thoroughly criticised by later generations of anthropologists, but it is important to acknowledge that, at the time, these quasi-scientific anthropological practices informed and legitimized ideologies of white supremacy that underpinned European colonial expansion and exploitation.

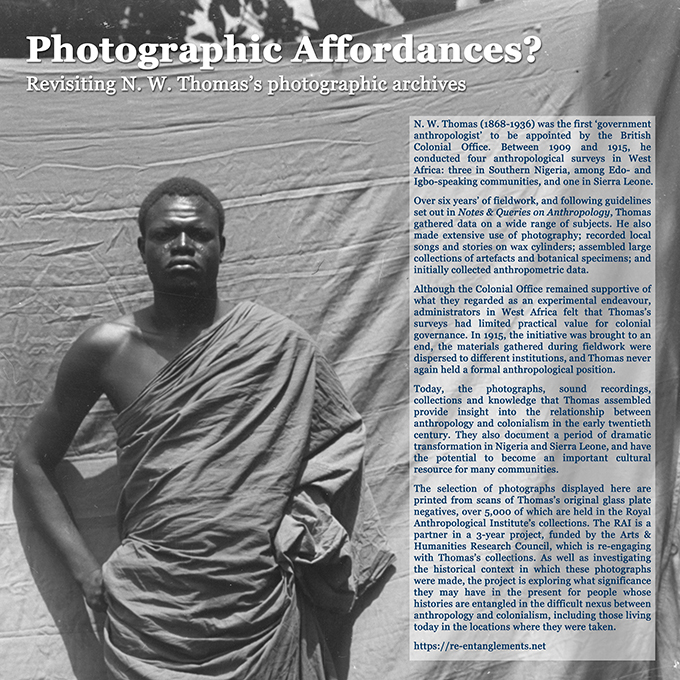

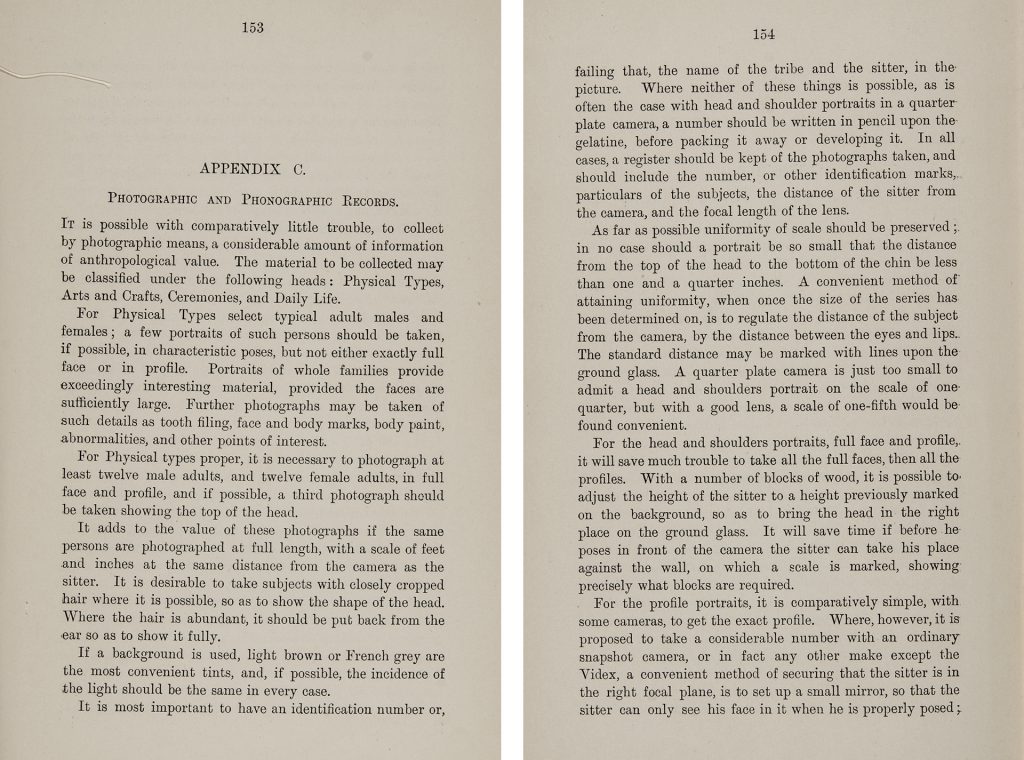

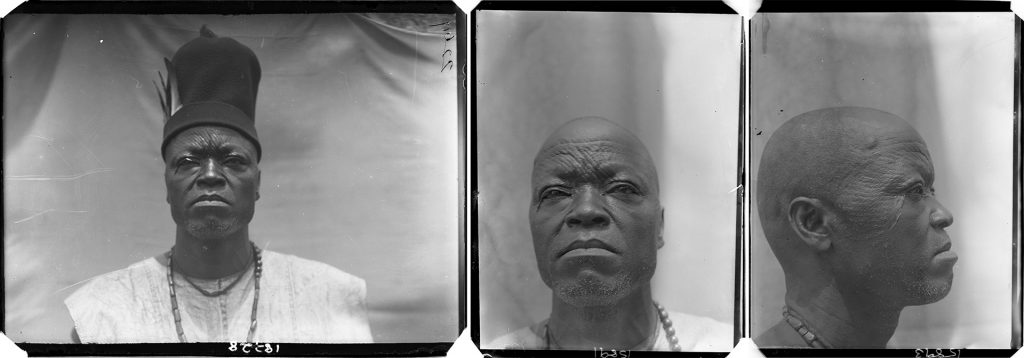

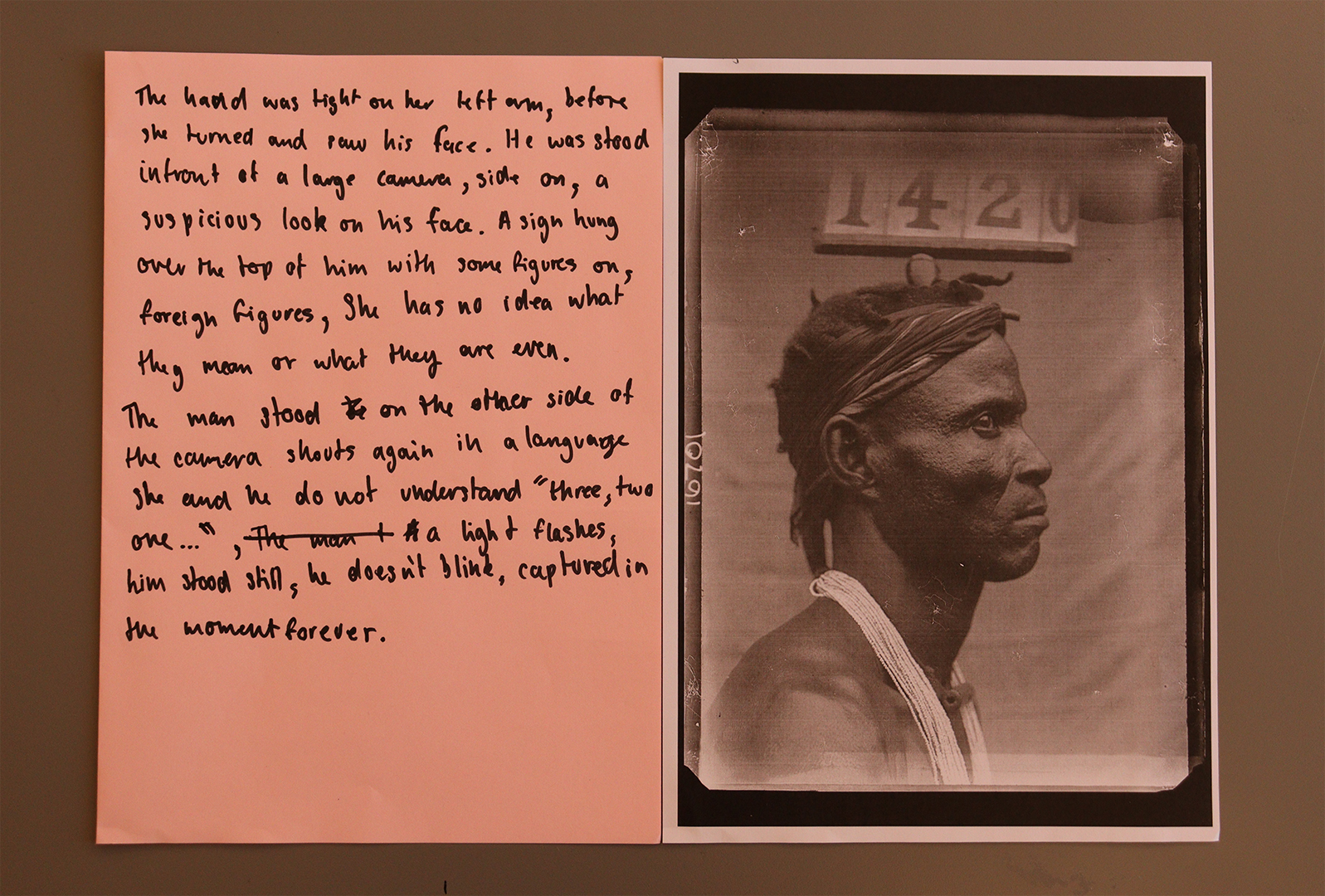

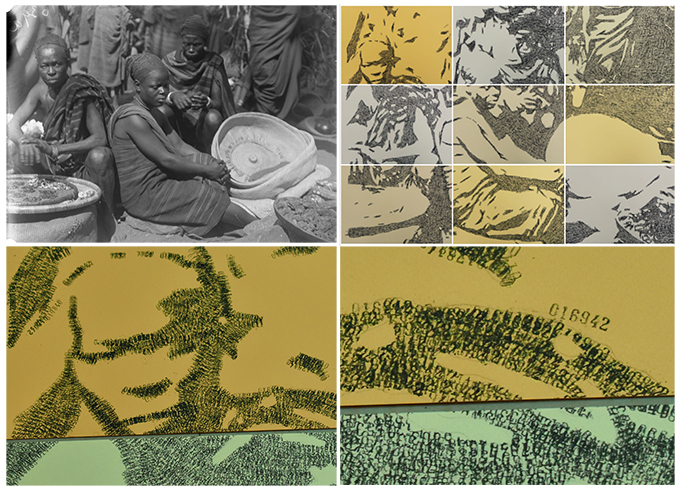

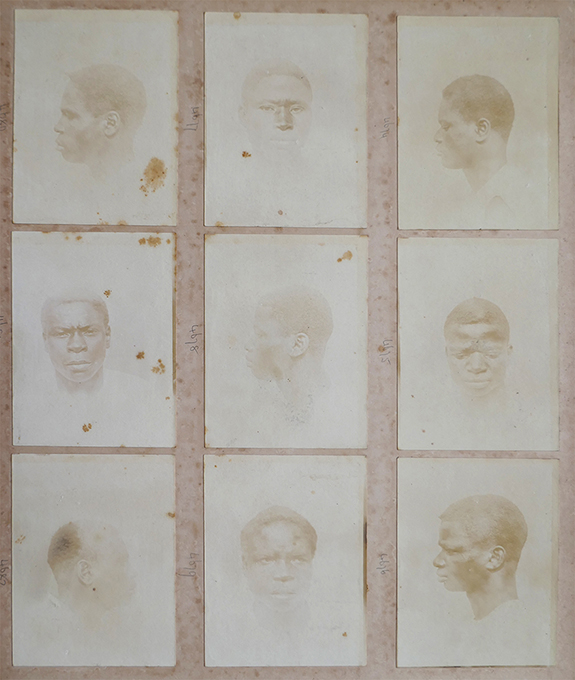

Since the 1860s, it had been recognised that photography could be an effective tool for anthropologists to document human physical characteristics and differences. By 1909, when Northcote Thomas set off on his first tour as Government Anthropologist in Southern Nigeria, the taking of anthropometric and physical type photographs had become standard practice in much anthropological fieldwork.

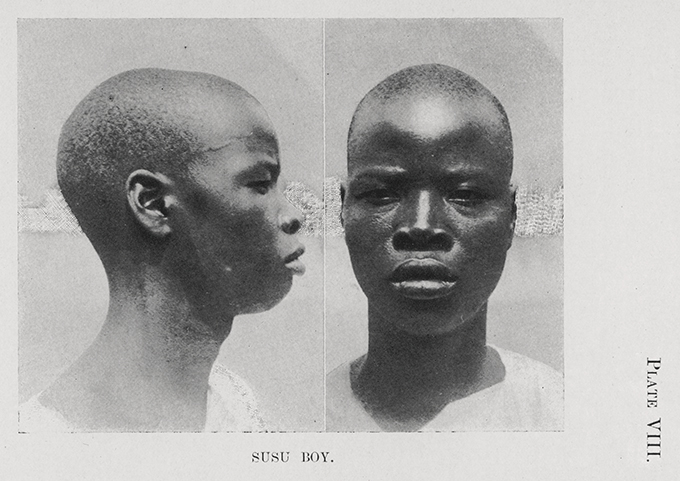

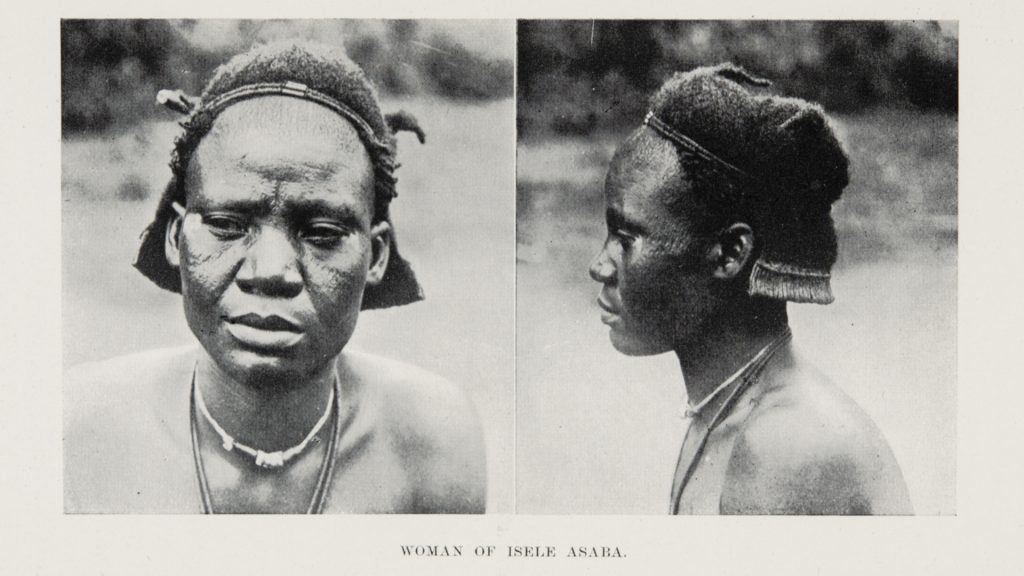

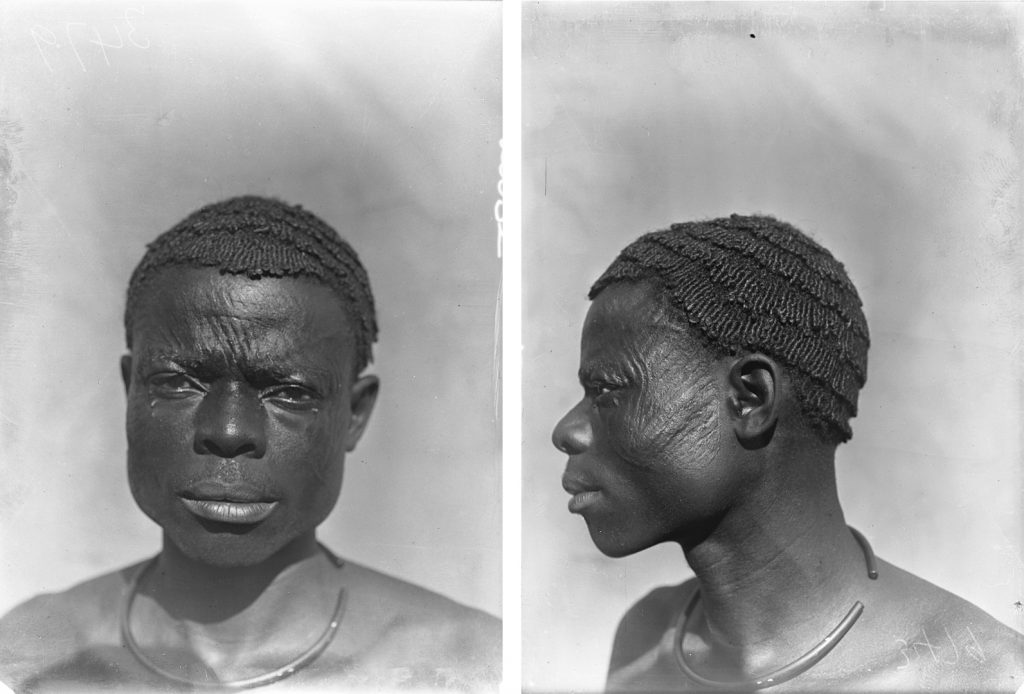

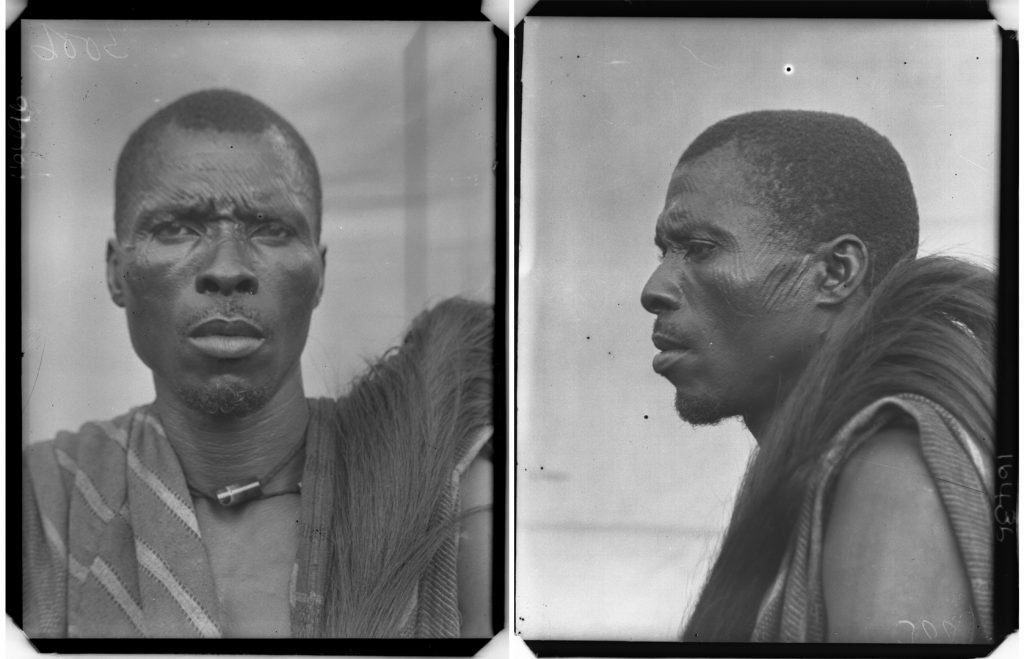

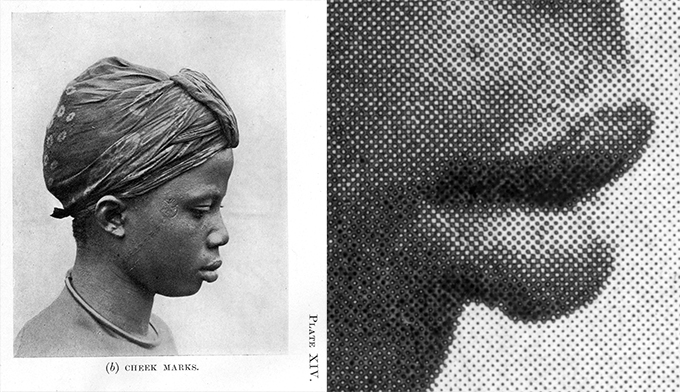

In 1896, for example, Maurice Vidal Portman had argued in the Journal of the Anthropological Institute that in ‘Properly taken photographs … will be found the most satisfactory answers to most of the questions in Notes and Queries on Anthropology’. This included the photographic documentation of social and cultural practices (ethnography), but also the physical characteristics of people. Explicitly referencing the anatomical sections in Notes and Queries, Portman noted that these could be recorded by taking ‘large photographs of the face, in full face and profile’.

Portman, a naval officer and colonial administrator, had collaborated with C. H. Read at the British Museum to produce a series of photographic albums documenting the inhabitants of the Andaman Islands in the Indian Ocean. These included examples of physical type and anthropometric photographs. A. C. Haddon described the method for making the latter in his entry on Photography in Notes and Queries as follows:

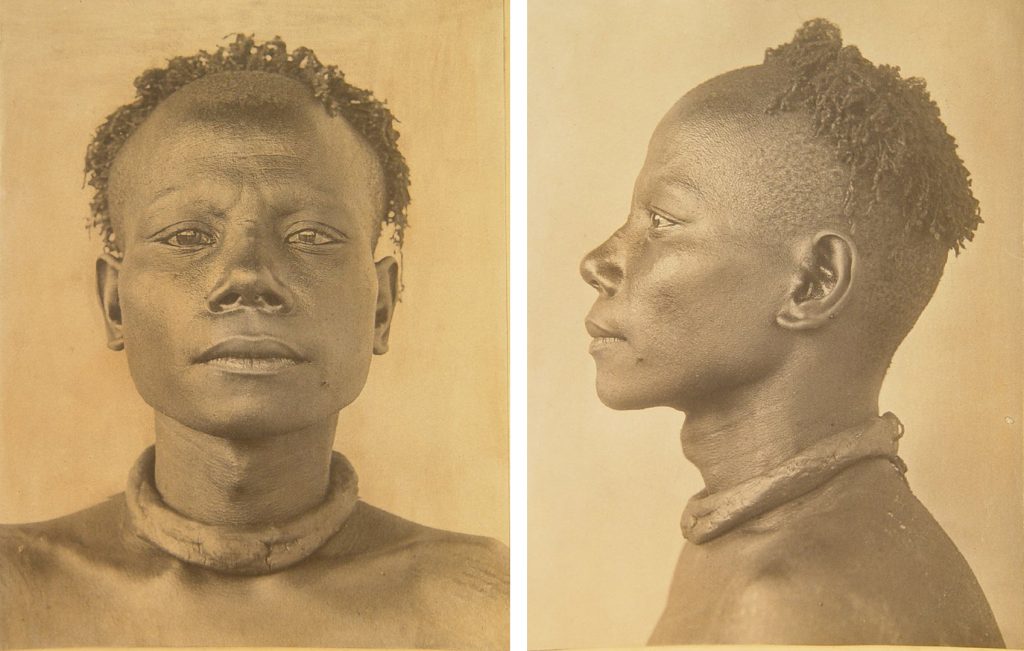

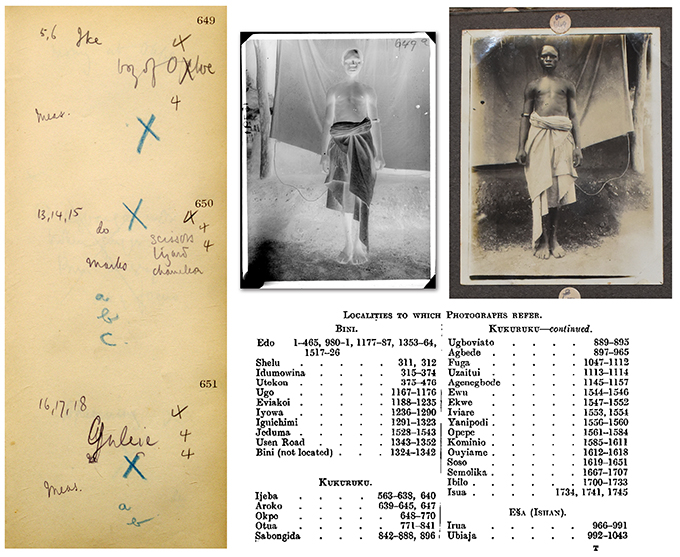

When the whole nude figure is photographed, front, side, and back views should be taken; the heels should be close together, and the arms hanging straight down the side of the body; it is best to photograph a metric scale in the same plane as the body of the subject. It is desirable to have a soft, fine-grained, neutral tinted screen to be used as a background.

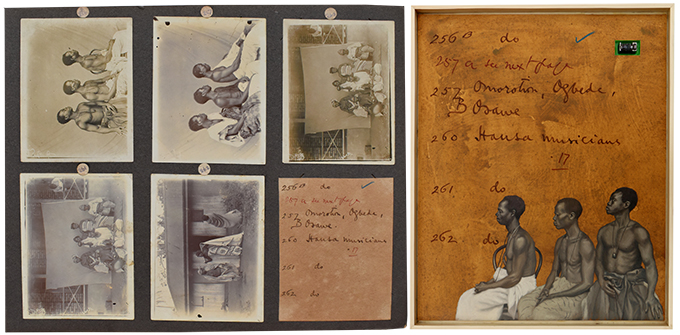

Northcote Thomas would have been familiar with Haddon’s guidelines in Notes and Queries as well as Portman’s article and Andamanese photographs. It is likely that he emulated Portman’s examples in his own photographic practice.

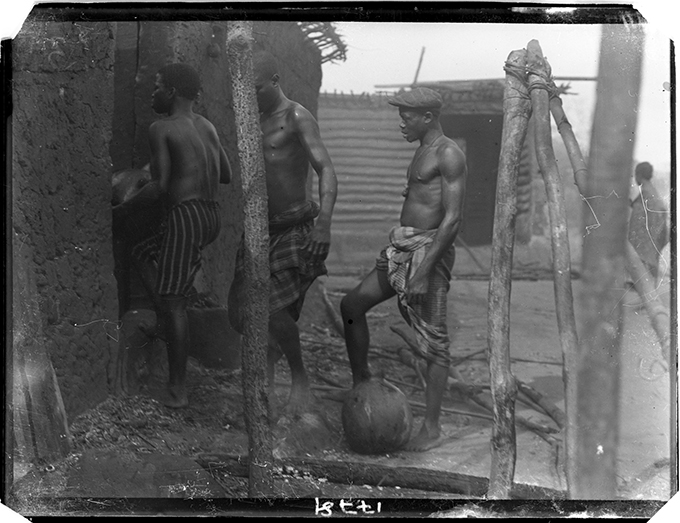

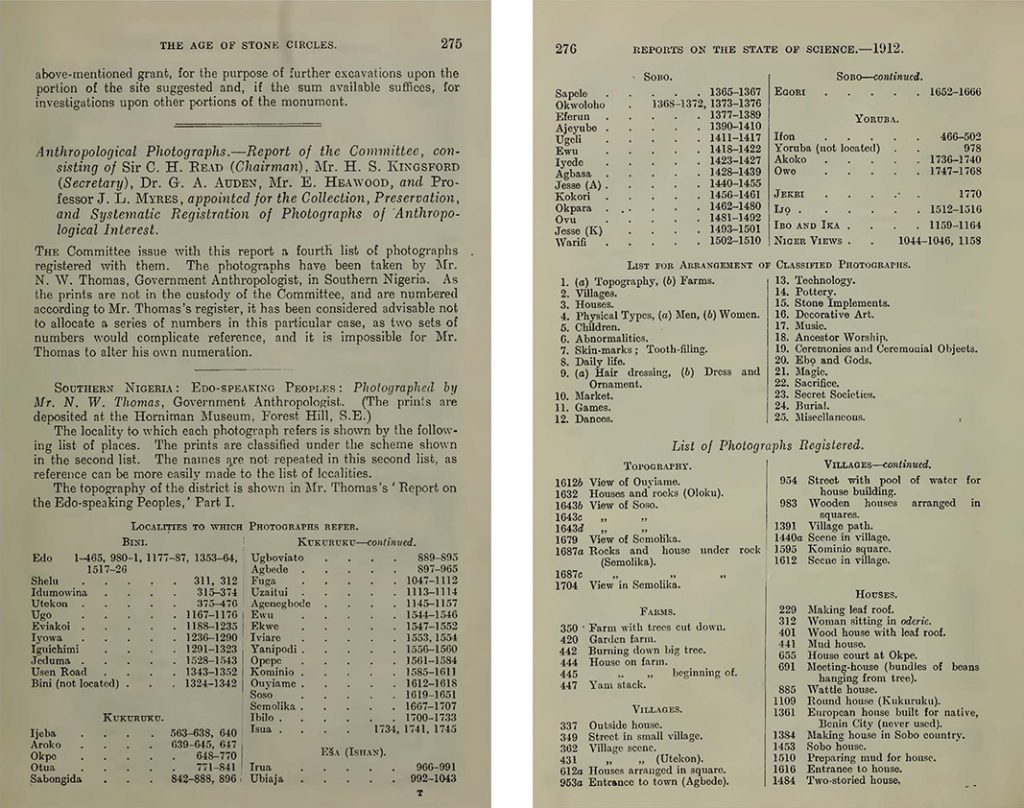

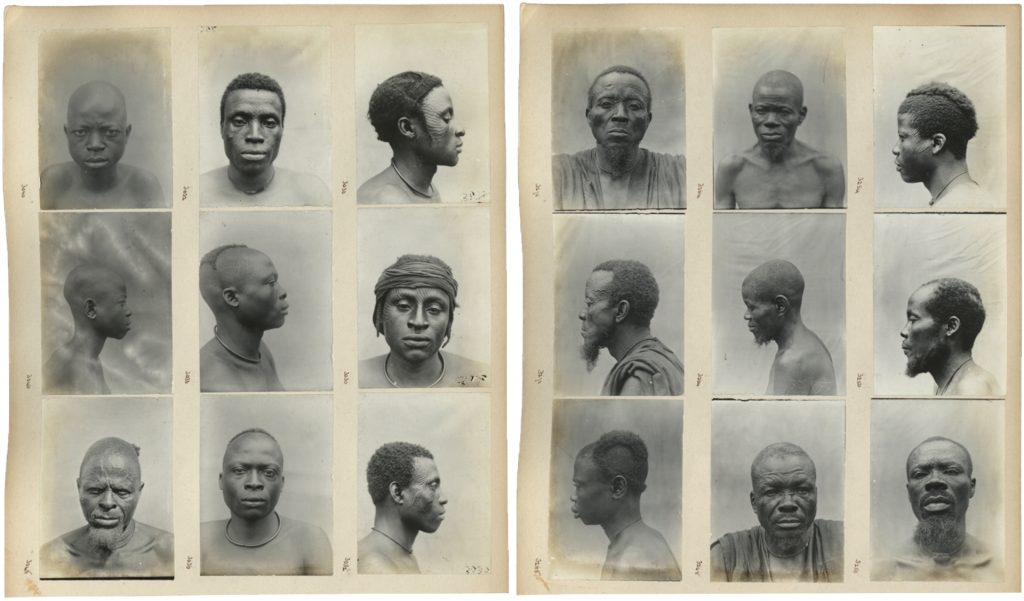

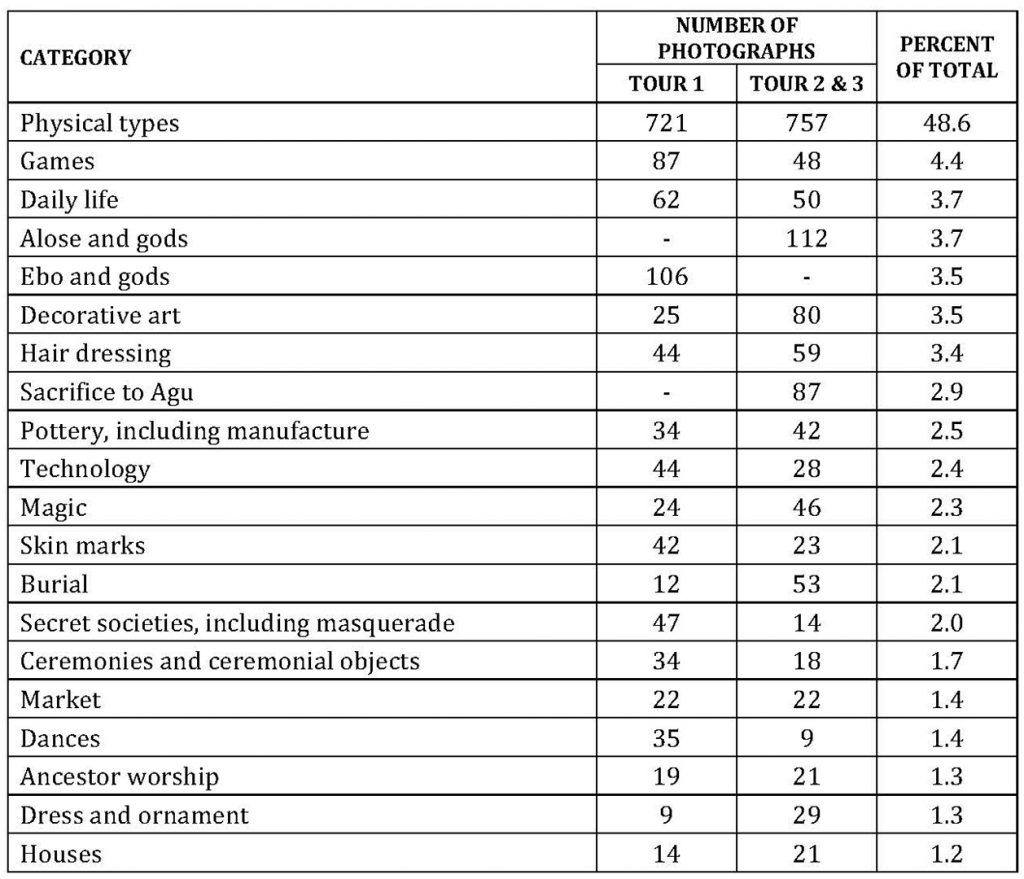

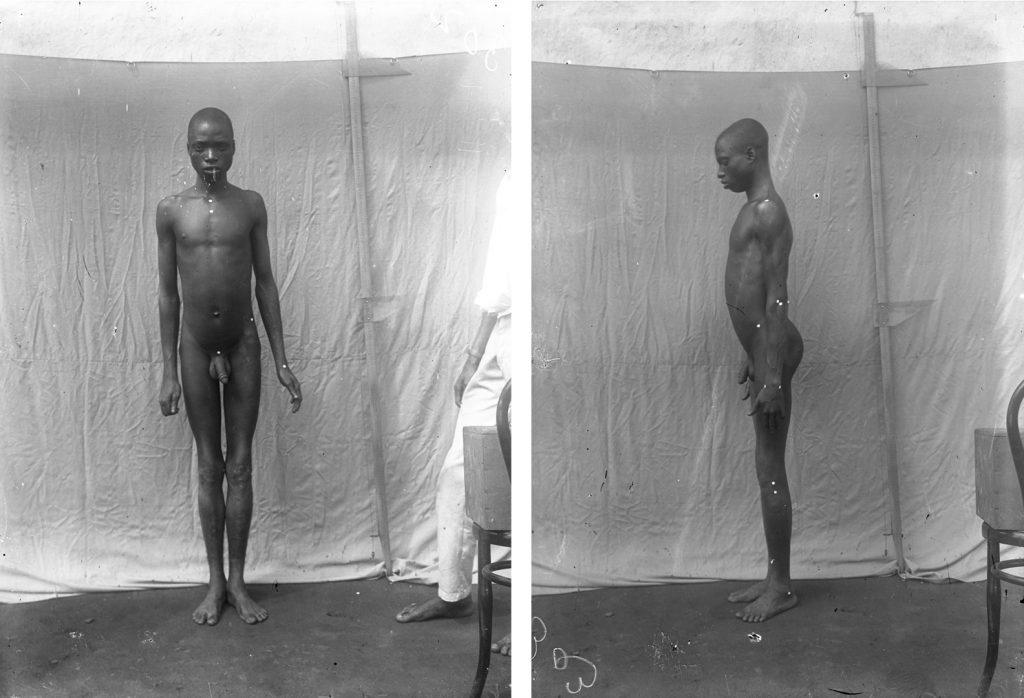

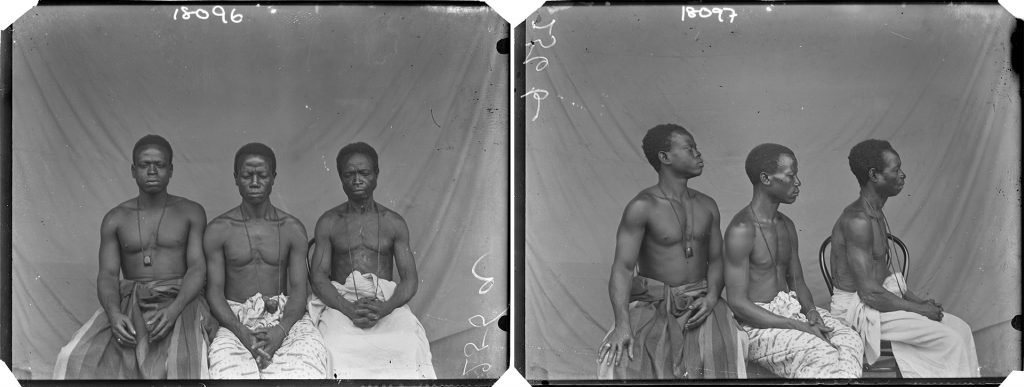

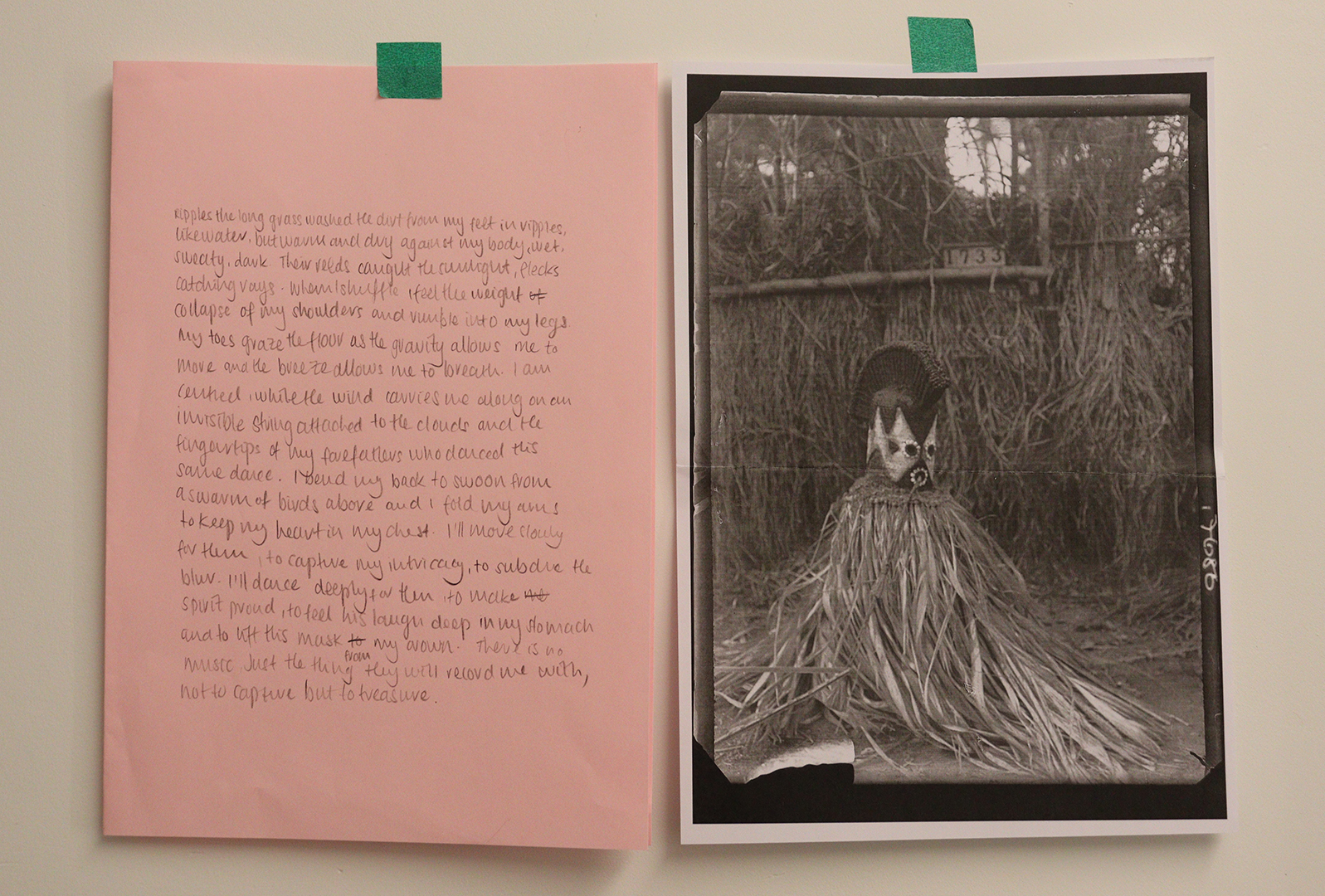

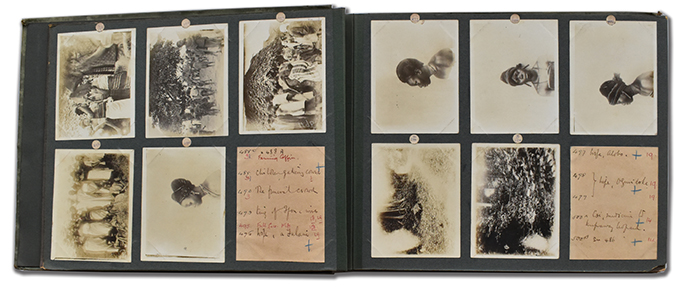

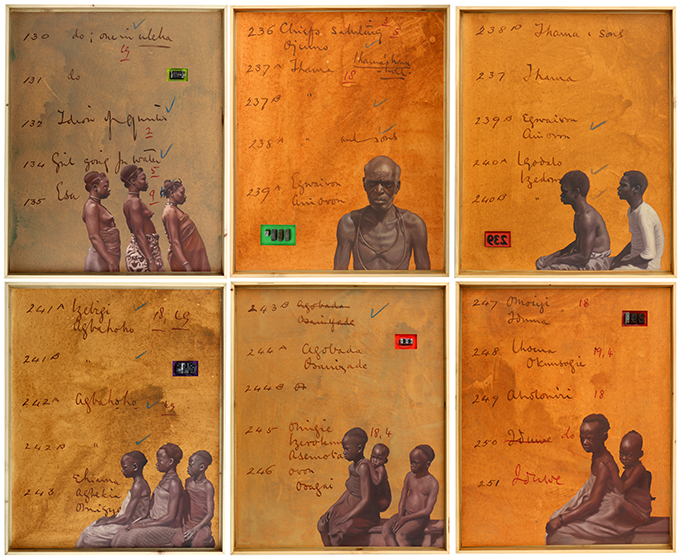

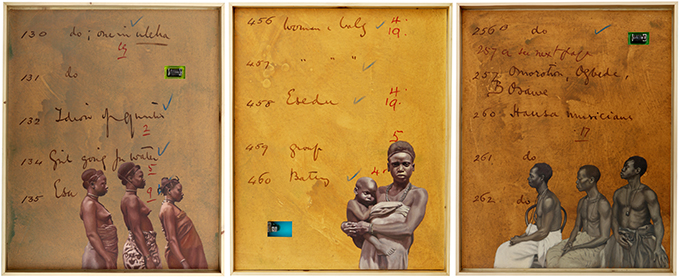

Thomas and his assistants made over 7,500 photographs during his anthropological survey work in Nigeria and Sierra Leone. Approximately half of those made in his three Nigerian tours were mounted in official photograph albums, copies of which were distributed to the Colonial Office in London, the Colonial Secretariat in Lagos and the Horniman Museum in South London (the latter intended for scholarly use). In these albums, the photographs were organised according to different categories. A statistical analysis of the 3040 photographs in the albums shows that nearly half were physical types (these were further subdivided into type photographs of men, women and children).

Thomas did collect anthropometric data during his 1909-10 survey of Edo-speaking communities in Nigeria, but he abandoned this practice in subsequent tours. In that first survey he also made a few full-length anthropometric photographs – of four individuals in total, evidently all taken in a single session – in which the subject was made to stand naked alongside a measuring scale as per the guidance in Notes and Queries.

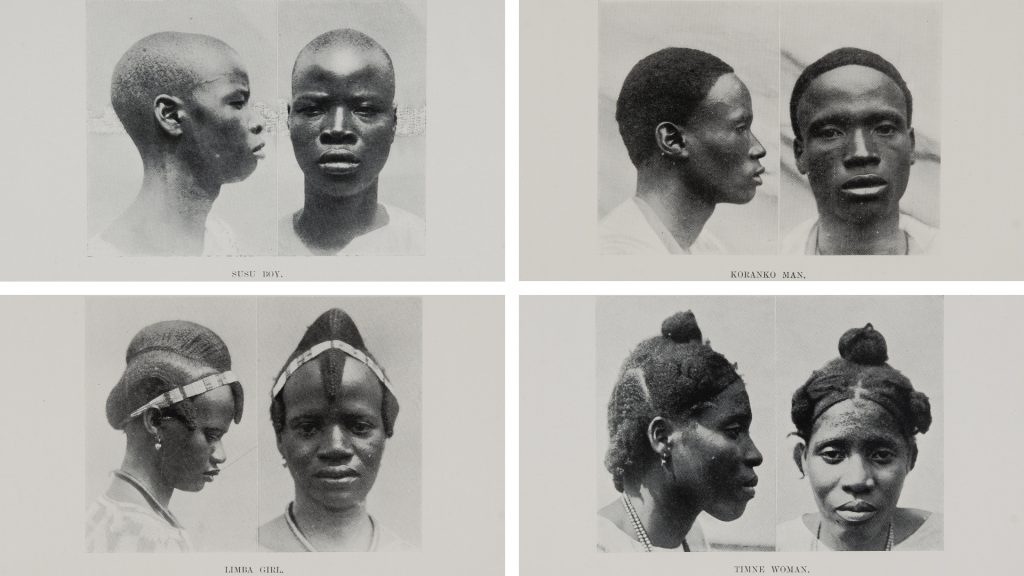

While a small number of physical type photographs were published in the official reports of Thomas’s 1910-11 and 1912-13 surveys of Igbo-speaking communities, and in his report of the 1914-15 Sierra Leone survey, no photographs were published in his Anthropological Report on the Edo-speaking Peoples of Nigeria (1910). Thomas did, however, provide detailed instructions for the taking of physical type photographs in an appendix of the Edo report. In addition to ‘physical types proper’, Thomas recommended taking portraits of family groups, and photographing subjects in more ‘characteristic poses’ (as opposed to the unnatural formalism of the full face and profile shots).

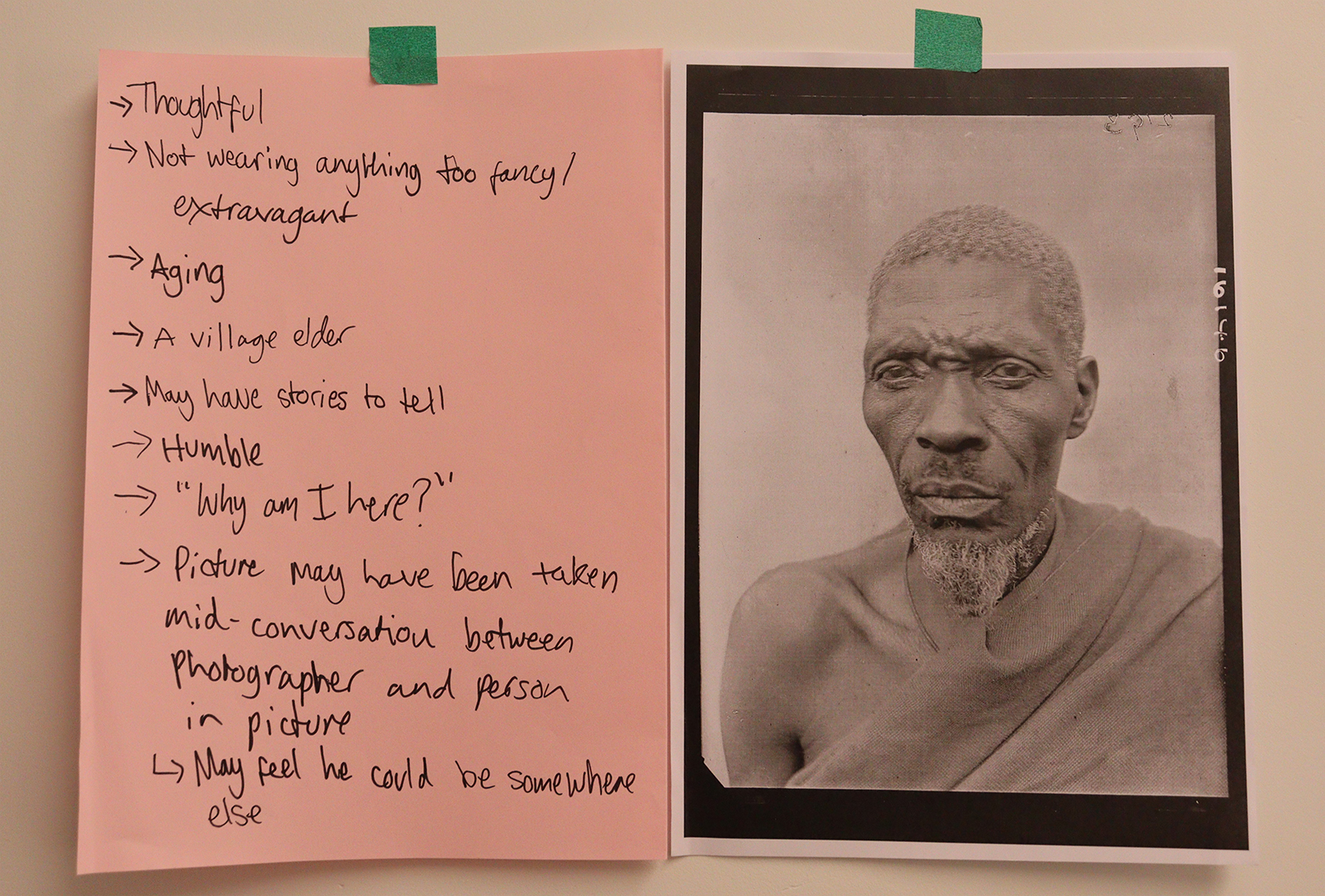

That Thomas should include such guidance, which was largely intended for colonial administrators, is somewhat puzzling since he provides only a very brief description of physical anthropology in the main text of the report, failing to explain why it should be of significance to colonial governance. Indeed, in the limited discussion he does provide, it is hard to arrive at any other conclusion than that, from a practical point of view, the considerable effort required in taking such photographs was quite pointless.

Certainly, the colonial authorities, both in West Africa and in London, had little interest in the physical type photographs, or, for that matter, in the anthropometric data that Thomas was at pains to collect during his first tour. This material was regarded as being of ‘a more purely scientific character’ and it was agreed that Thomas could pursue such work only insofar as it did not ‘encroach materially on the more “practical” side of the enquiry’ – the ‘examination of native law and custom’ being the work for which he was ‘primarily engaged’.

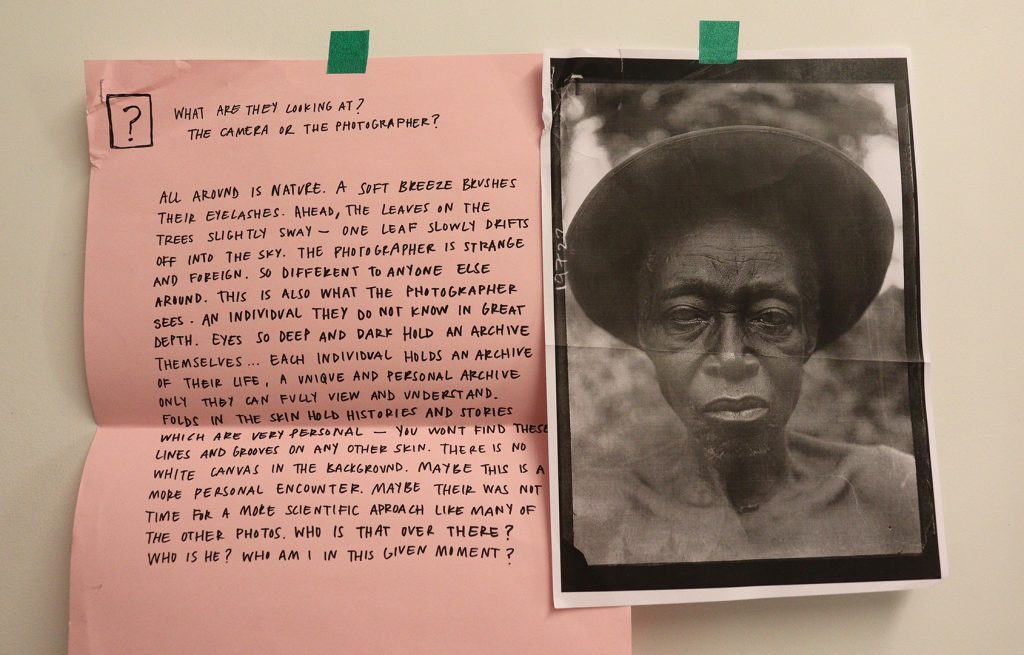

The disconnect between the scientific inquiries of physical anthropology and the supposed practical value of ethnography (what became known as social anthropology) is evident in the incredulity with which a request from Thomas, in July 1910, to supply the Natural History Museum with 20 ‘enlarged photographs, representative of the racial types of the Central Province [of Southern Nigeria]’ was met by the Colonial Office. As the senior Colonial Office clerk with whom Thomas had closest contact remarked in an internal minute: ‘I cannot imagine what a natural history collection wants to do with ethnographical pictures’. That the physical type photographs were mistaken for ‘ethnographical’ ones by the Colonial Office suggests that there was little understanding of these photographs or the purpose they were intended to serve. Indeed, in a letter to W. P. Pycraft, Head of the Anthropology Sub-Department at the Natural History Museum in 1920, Thomas admits that, with regard to physical types, ‘no one cares much for them’.

Given that Thomas was himself much more interested in ethnological and linguistic matters, and seemingly had little to say about physical anthropology, it is curious that he expended so much energy making physical type photographs. One can only speculate that his motivation lay in the sense that this was an essential dimension in the performance of anthropology and that adherence to the methodological orthodoxies of Notes and Queries was a signal of his professionalism.

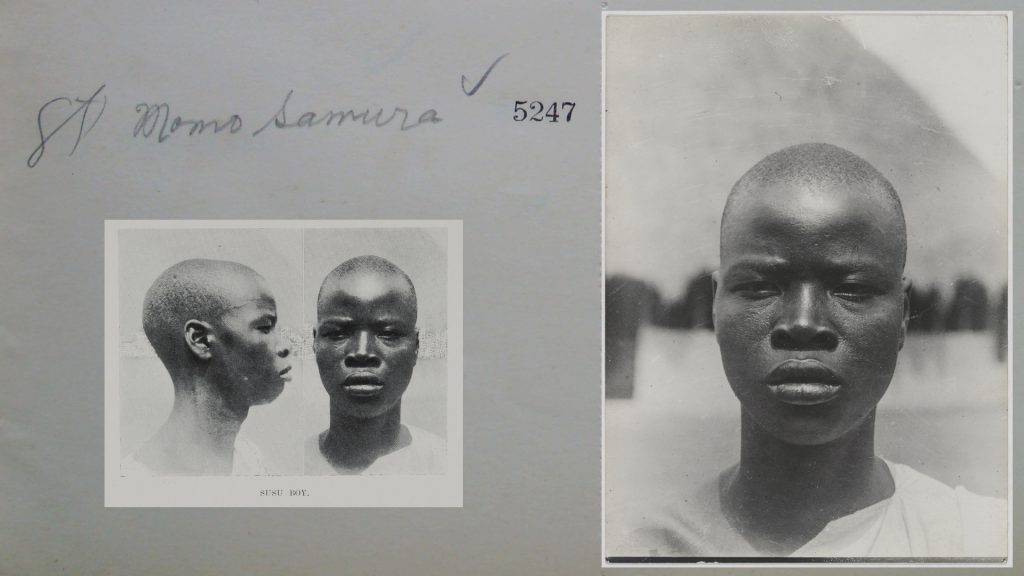

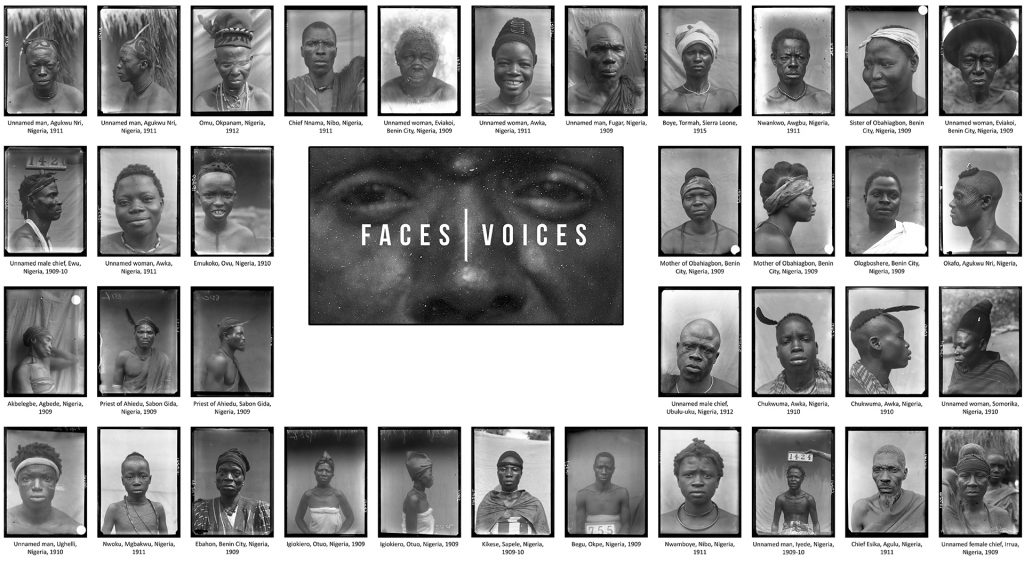

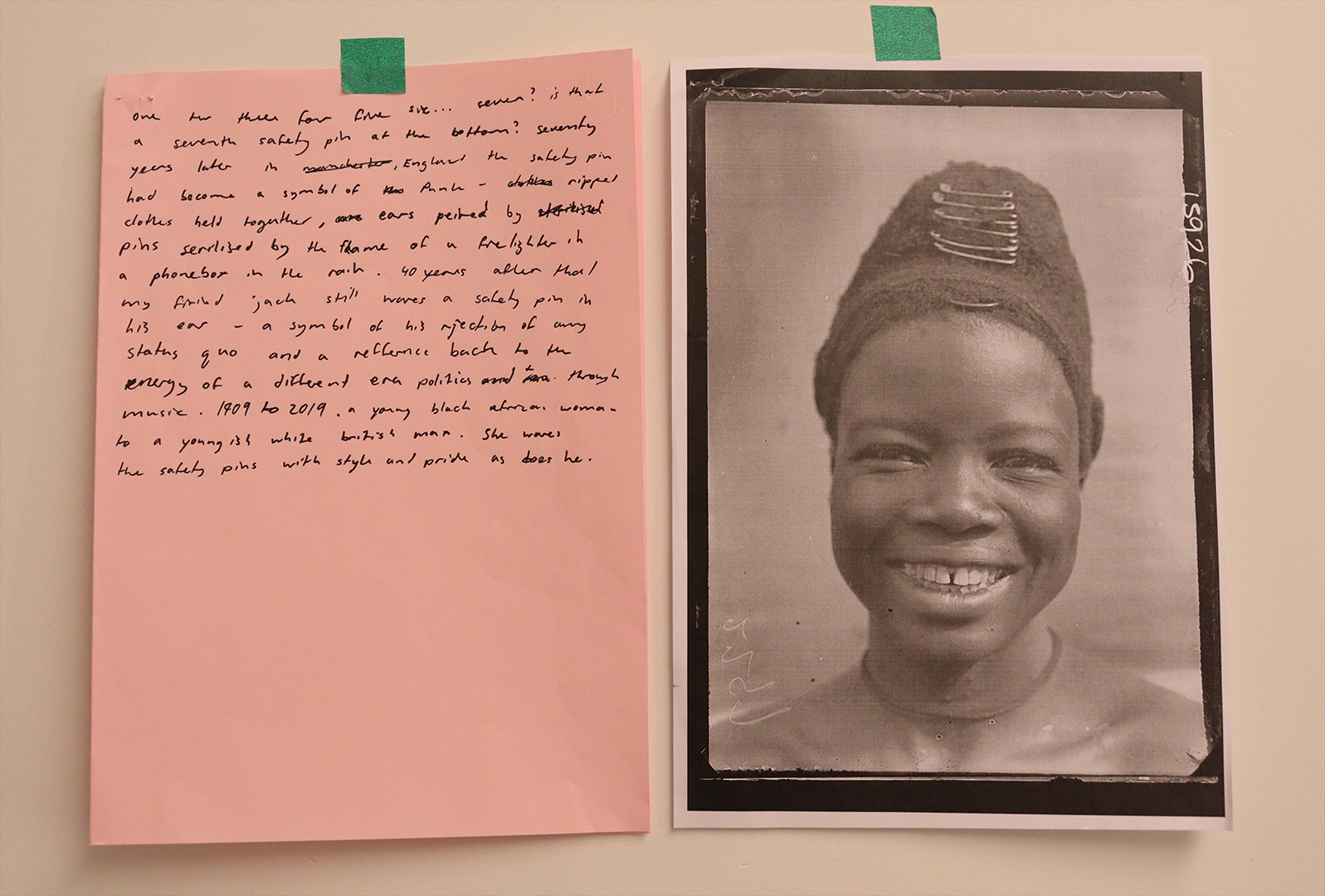

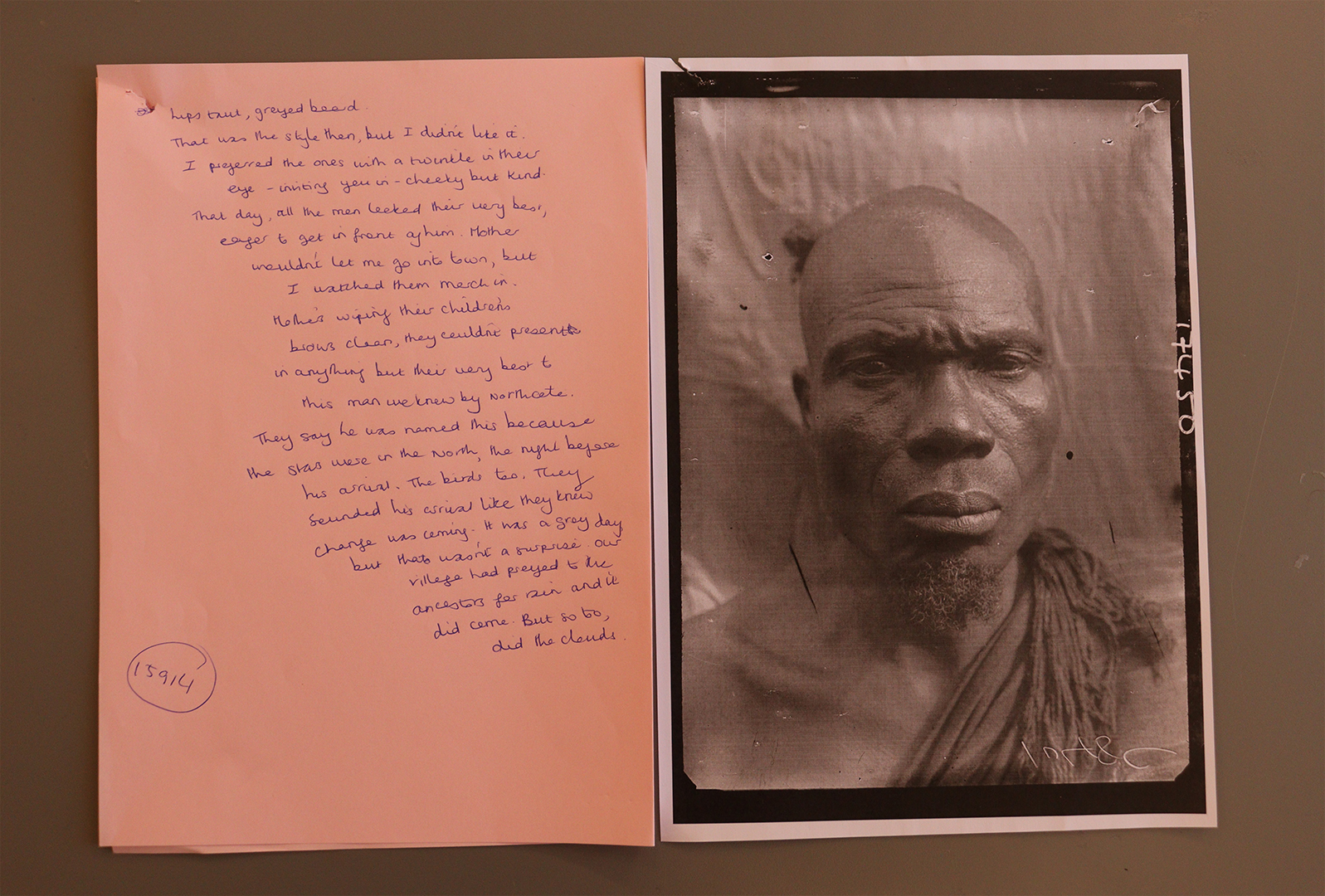

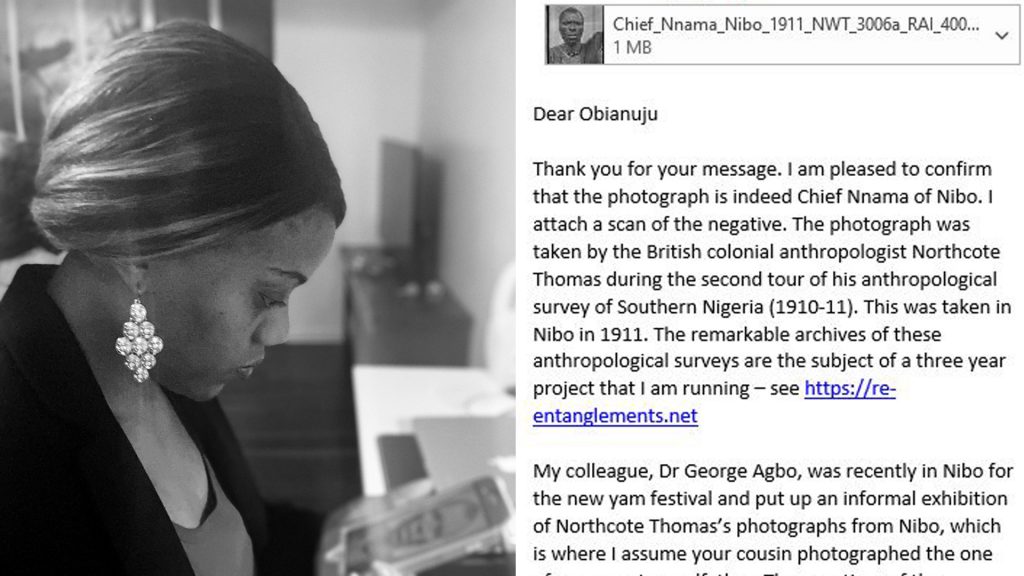

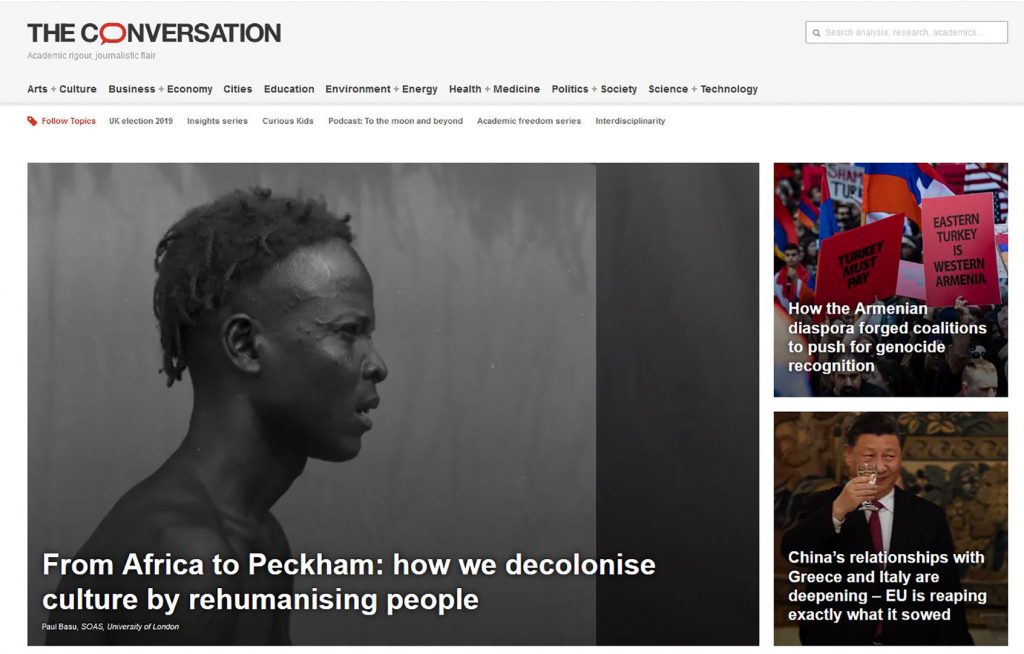

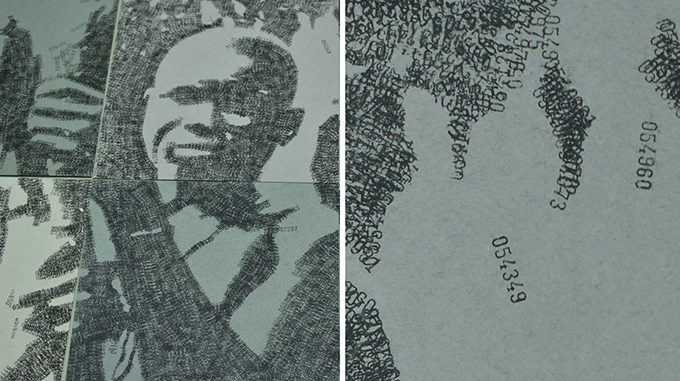

Of the many hundreds taken, only 30 physical type portraits were actually published in Thomas’s Igbo and Sierra Leone reports. These were accompanied by captions identifying the subjects only by place or ‘tribe’. Here we see further evidence of how people were stripped of their names and individuality and reduced in these ‘scientific’ reports to anonymous representatives of particular ‘types’. We should note, however, that Thomas was in fact careful to record the names of many of those he photographed in his photographic register books. We know, for example, that ‘Man of Awka’ (Igbo report, Part I, Plate IIa) is a blacksmith named Muobuo, aged about 40 years, ‘Woman of Nibo’ (Igbo report, Part I, Plate IIIa) is Ozidi, while ‘Limba girl’ (Sierra Leone report, Part I, Plate XVII) is Kaiyais, photographed in Kabala, and ‘Susu boy’ (Sierra Leone report, Part I, Plate VIII) is young Momo Samura, photographed in Somaia.

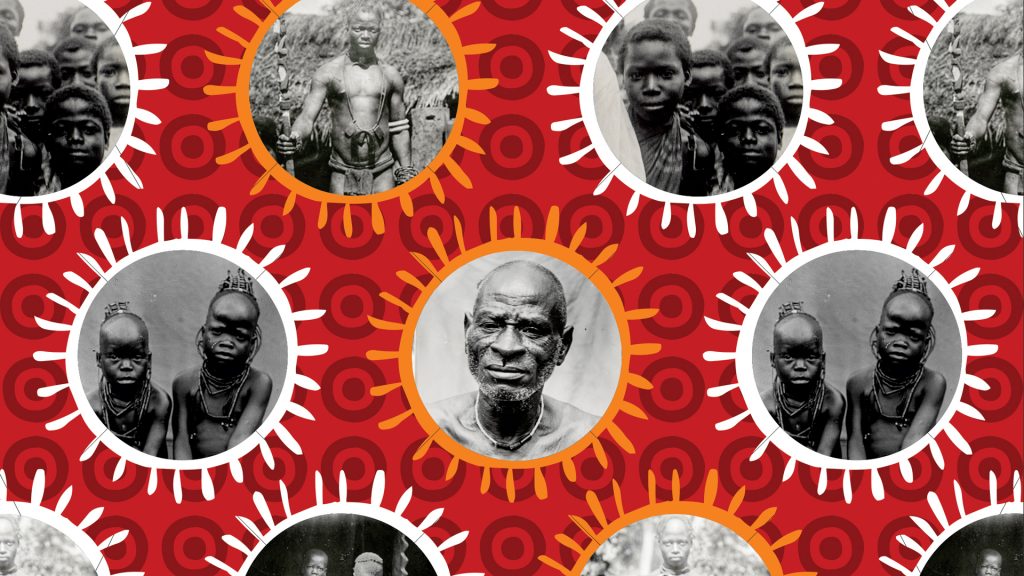

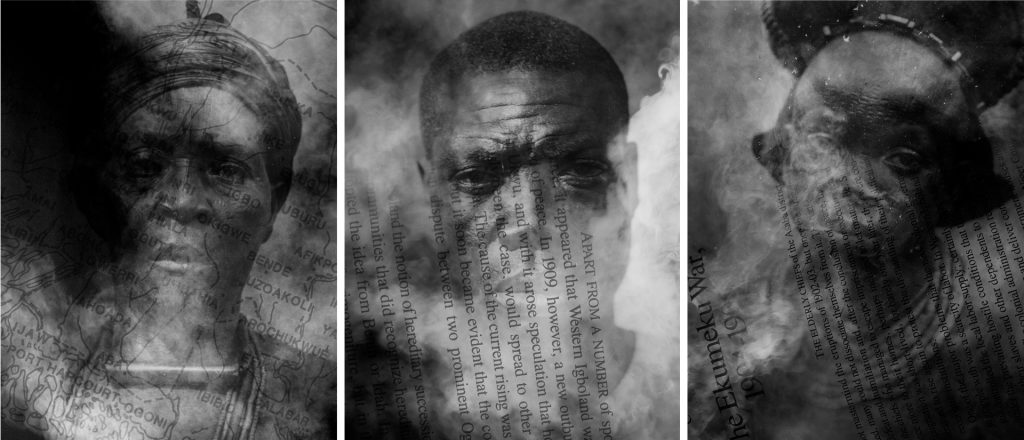

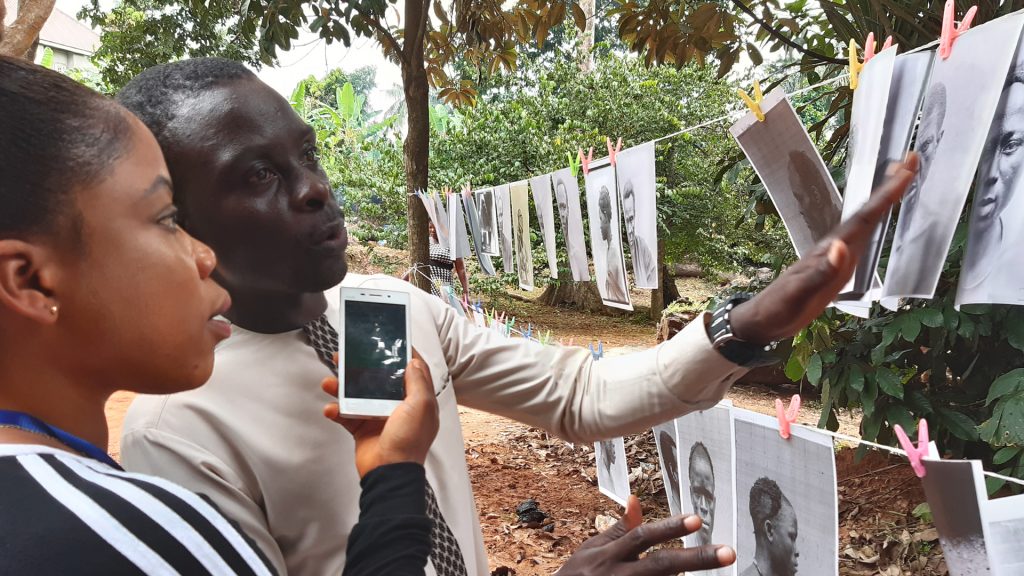

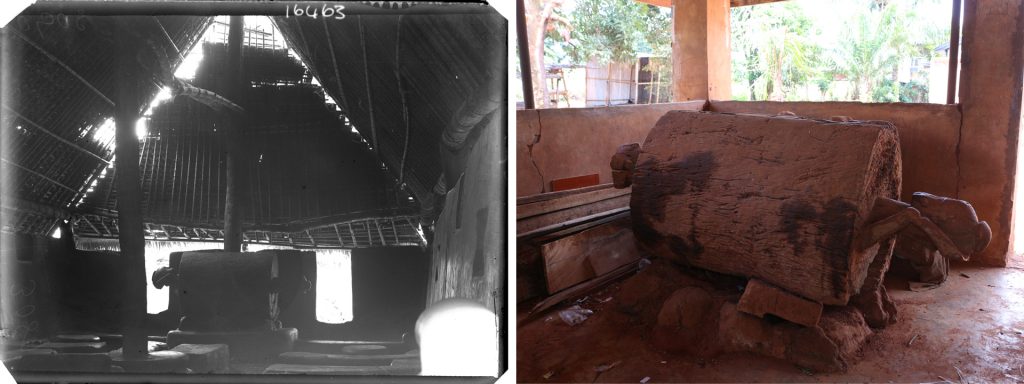

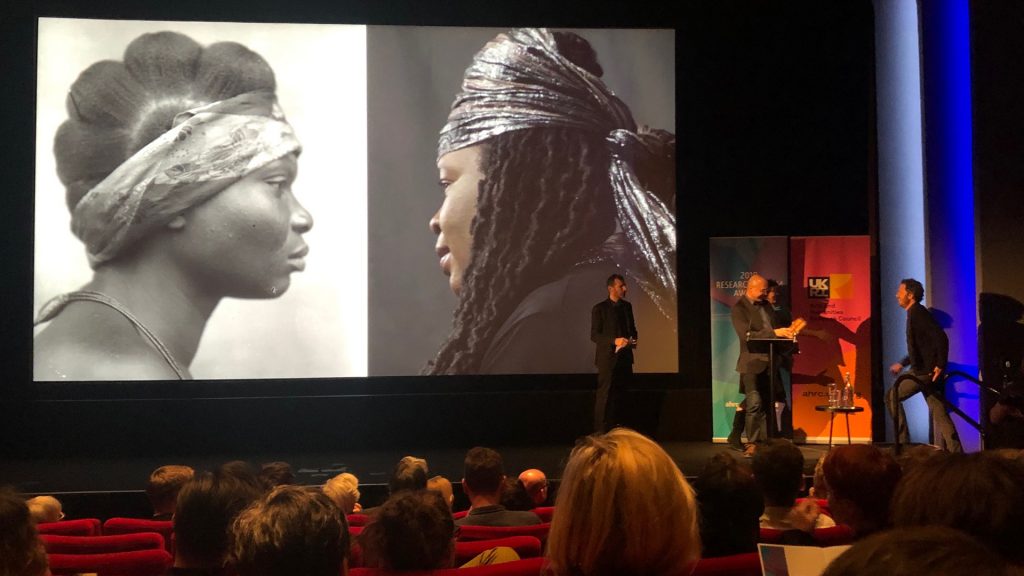

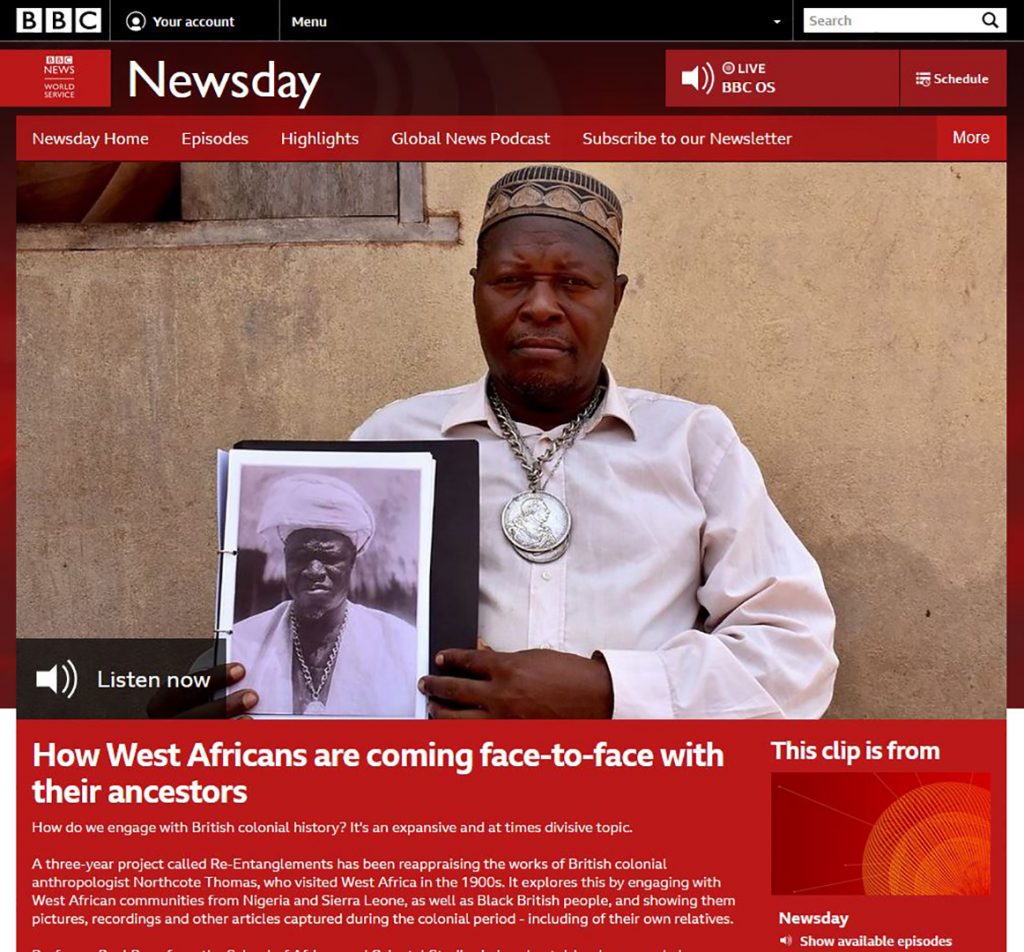

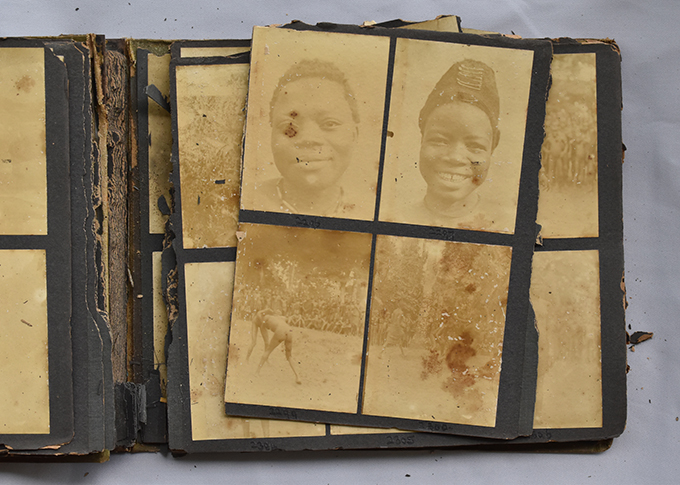

If anthropological photography afforded the dehumanization of individuals, reducing people to ‘specimens’ to be collected and ordered by type, the archive now affords the possibility of reuniting the subjects of these portraits with their names, which, in some small way, rehumanizes them and returns to them their individuality. Since we also been able to identify where each photograph was taken, it has been possible to bring the photographs back to Nigeria and Sierra Leone and present these portraits to the descendants of those photographed. In these contexts, rather than toxic traces of a colonial anthropological project, these photographs are treasured by family members as precious portraits of ancestors.

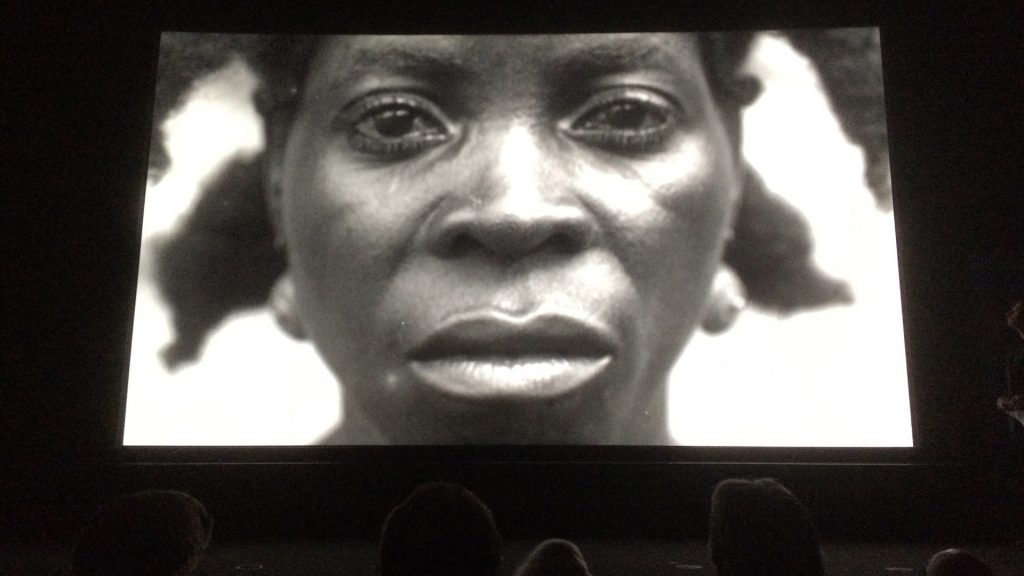

Furthermore, contrasting with the small selection of physical type photographs that were published in Thomas’s reports, in which subjects appear lifeless and inexpressive, in the many hundreds of unpublished prints and negatives we find a great diversity of expression. The informality of many of the unpublished physical types, in which subjects may also be found smiling and even giggling, though failing in the performance of ‘science’, affords a glimpse into the human interaction between subject and photographer-anthropologist that was, after all, at the heart of these fieldwork encounters. We have explored some of the complexity surrounding these photographs, and the multiple ways in which we can ‘read’ them, in the film Faces|Voices.

![Physical type photograph installation in the [Re:]Entanglements exhibition at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/08/Physical_type_photograph_installation_Re-Entanglements_exhibition_Museum_of_Archaeology_and_Anthropology_Cambridge_re-entanglements.net_-1024x683.jpg)

![[Re:]Entanglements project Flickr site](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Reentanglements_Flickr_site_Nibo_screenshot_re-entanglements.net_-1024x576.jpg)

![Scenes from opening of [Re:]Entanglements exhibition, National Museum, Lagos](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/National_Museum_Lagos_exhibition_opening_re-entanglements.net_.jpg)

![[Re:]Entanglements exhibition view, National Museum, Lagos](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/National_Museum_Lagos_exhibition_view_re-entanglements.net_.jpg)

![[Re:]Entanglements exhibition view, National Museum, Lagos](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/National_Museum_Lagos_exhibition_view_2_re-entanglements.net_.jpg)

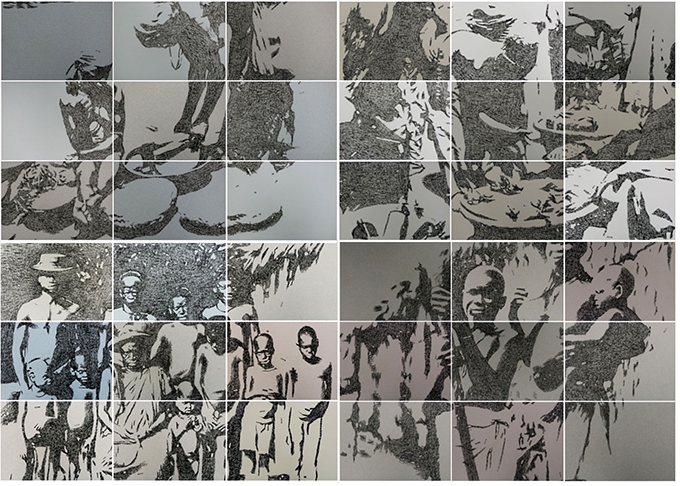

![Kelani Abass [Re:]Entanglements Contemporary Art & Colonial Archives Exhibition, National Museum Lagos](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Kelani_Abass_exhibition_National_Museum_Lagos_re-entanglements.net_.jpg)

![Interviewing project participant for Faces/Voices video installation, [Re:]Entanglements project, 2018](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Re-entanglements_Faces_Voices_video_shoot_02.jpg)

![Faces/Voices video installation, [Re:]Entanglements project, 2018](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Re-entanglements_Faces_Voices_video_shoot_01.jpg)

![Interviewing project participant for Faces/Voices video installation, [Re:]Entanglements project, 2018](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/Re-entanglements_Faces_Voices_video_shoot_03.jpg)