Labelling matters

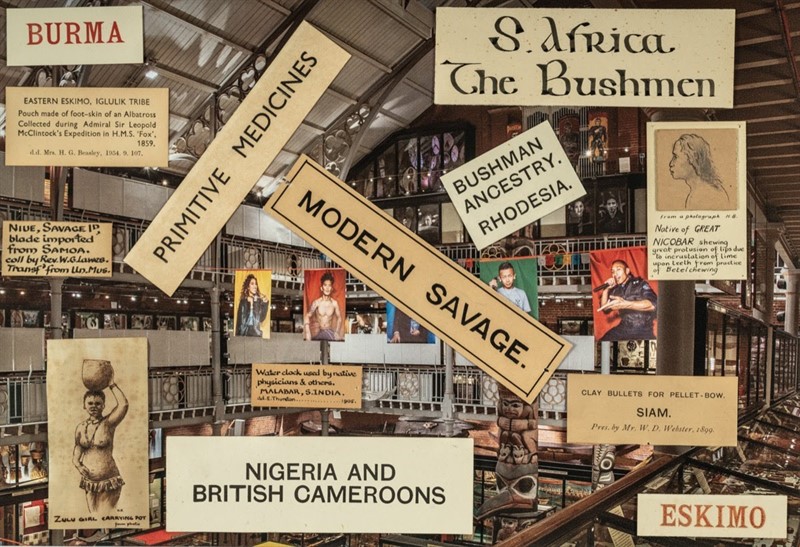

As part of the broader movement to decolonise museums, the labels used to identify and describe objects in collections has attracted critical attention. In many cases, the language used on museum labels, particularly in ethnographic museums, is outdated, offensive and inappropriate. This includes the labelling of particular ethnic or cultural groups.

Prominent initiatives to rethink the use of museum texts include the Words Matter programme and publication organised by the Research Centre for Material Culture in The Netherlands and the Labelling Matters project at the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford. Both organisations are partners in the Museum Affordances / [Re:]Entanglements project.

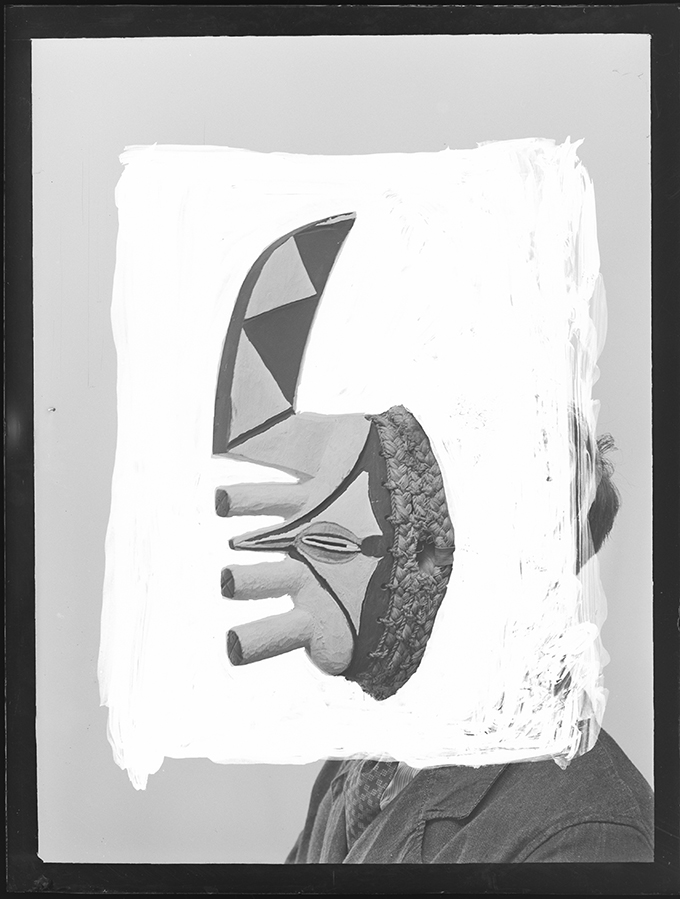

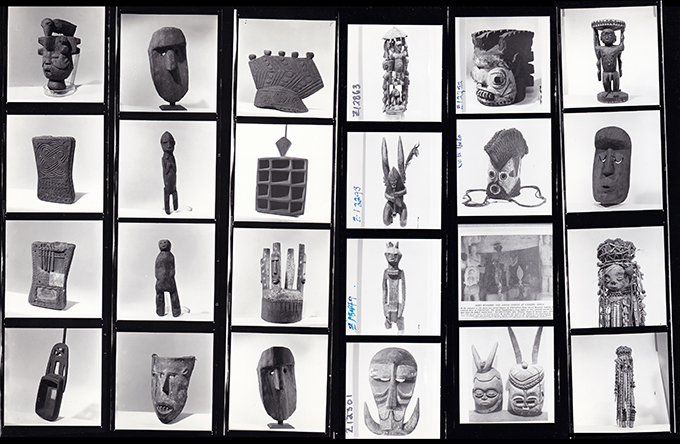

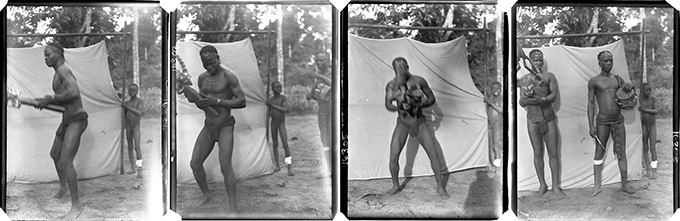

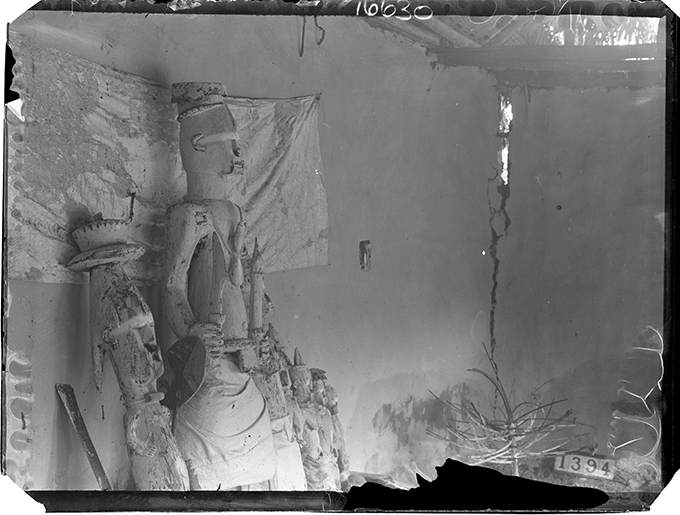

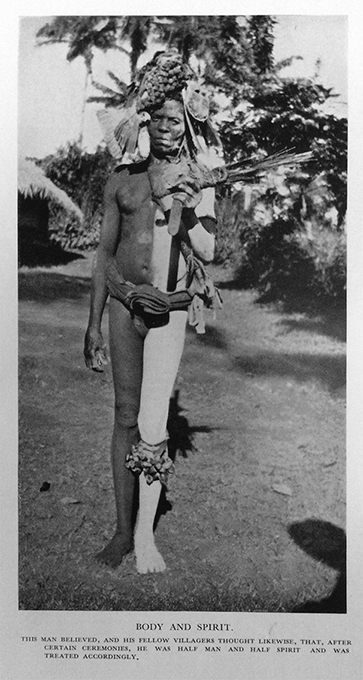

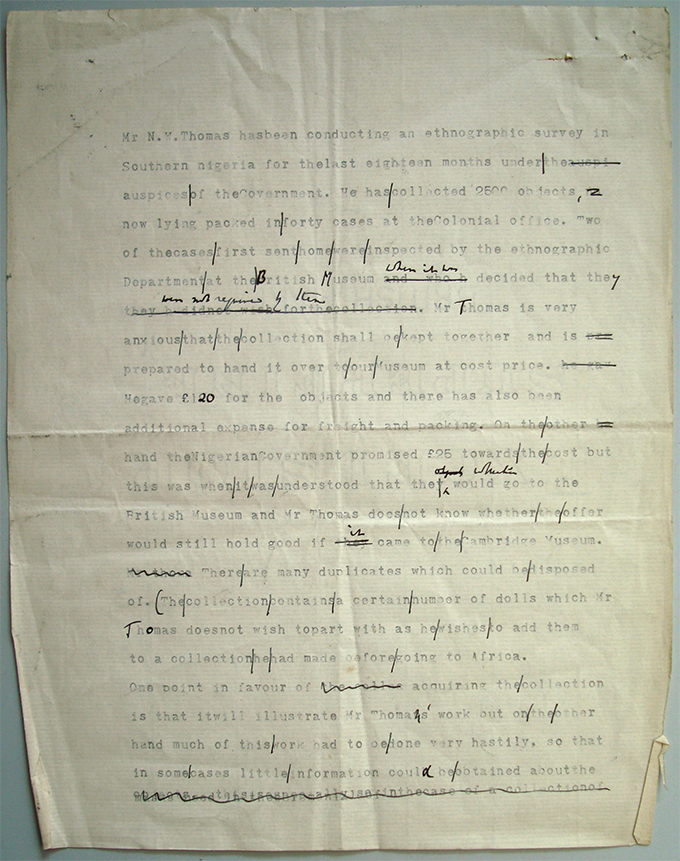

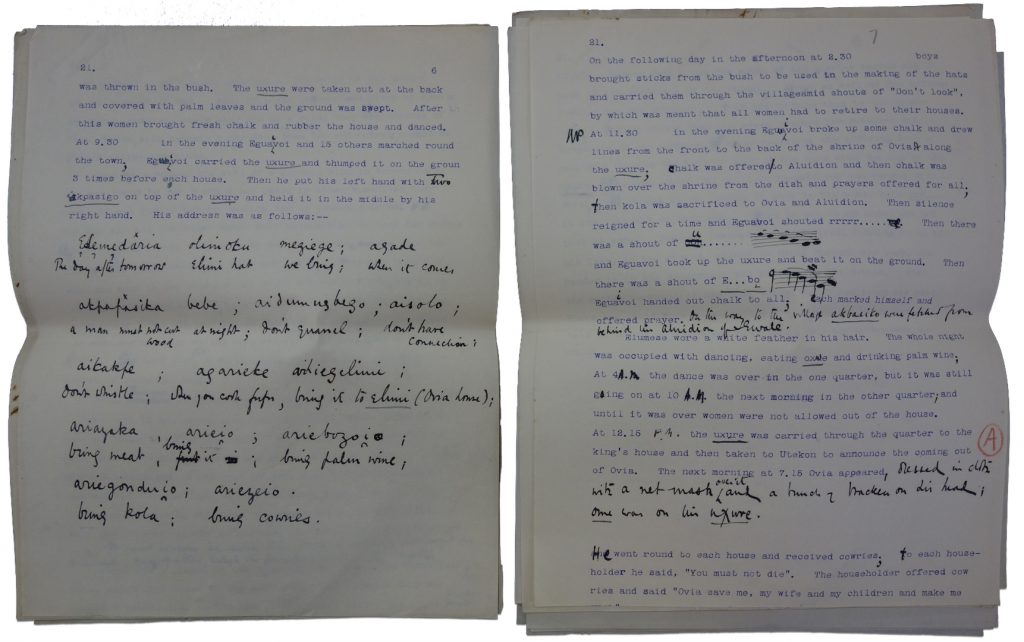

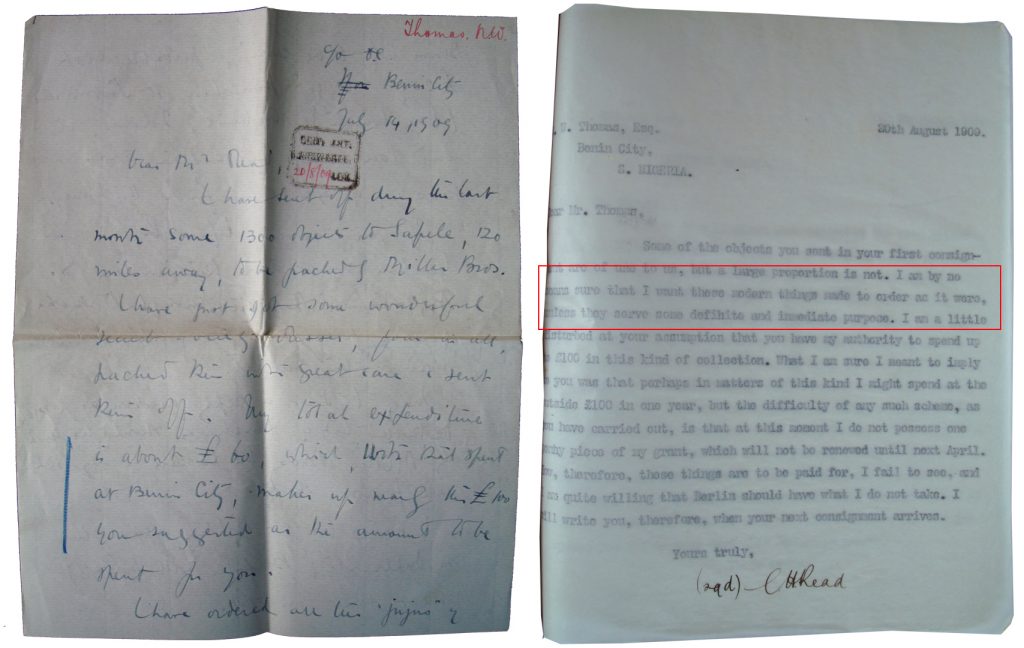

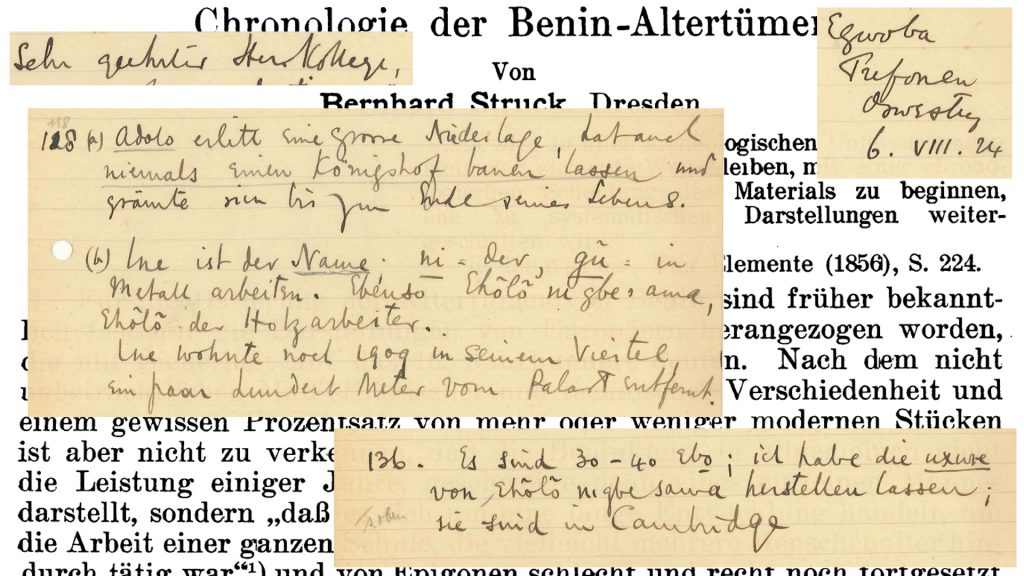

A main focus of this work has been to attend to the labelling of objects in public galleries. This has resulted in various gallery interventions where alternative texts have been produced to ‘re-narrate’ the displays. However, as Ciraj Rassool has noted in his article ‘Museum Labels and Coloniality’, textual records become attached to cultural artefacts from the moment of their acquisition. It is at this moment that they are first classified, often according to ‘tribal’ categories that themselves reflect colonial ideologies. This is part of a process in which objects, as well as people, become ‘entribed’.

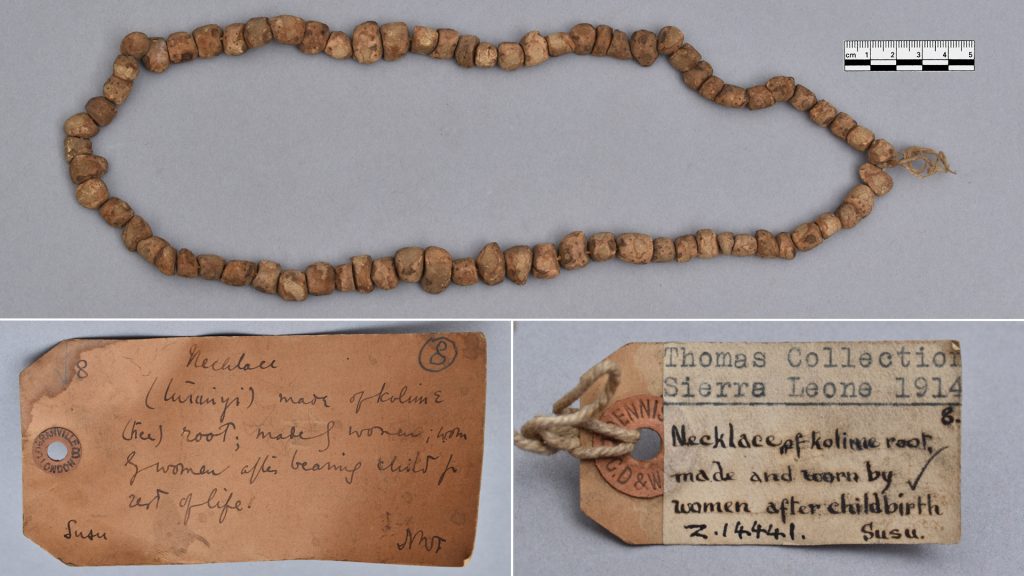

The labelling and re-labelling of collections is an important part of an object’s biography. Even when old labels have been removed, it is important that they are retained as part of the historical record. In this article, we take a closer look at some of the historical labels that are, or have been, attached to objects assembled by Northcote Thomas during his anthropological surveys in Nigeria and Sierra Leone.

N. W. Thomas collection labels

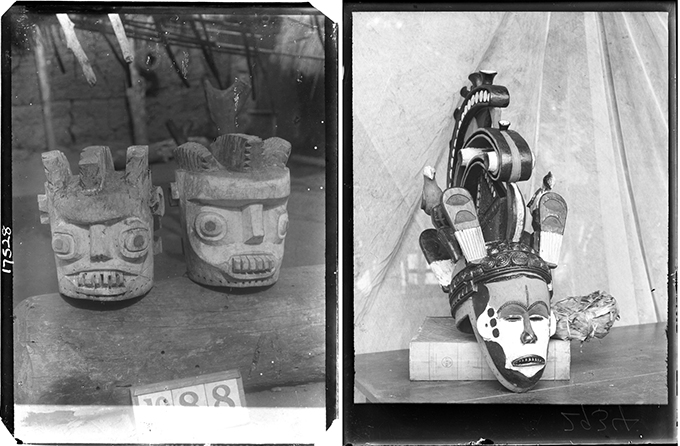

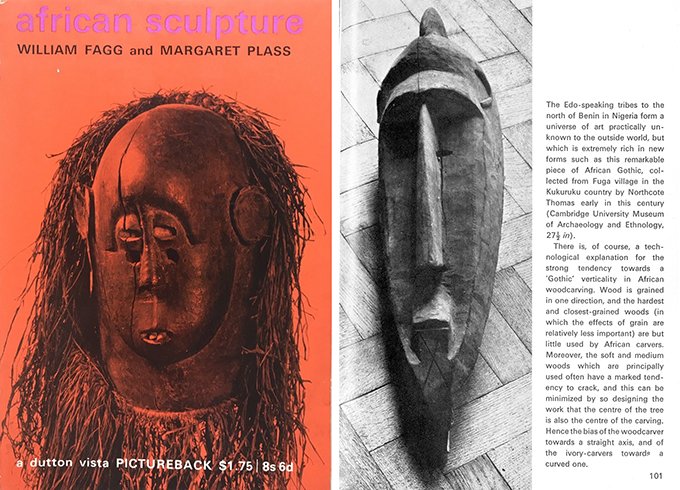

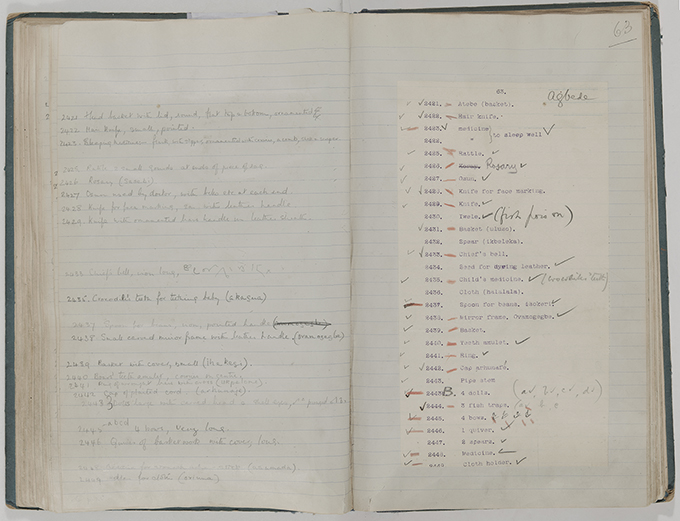

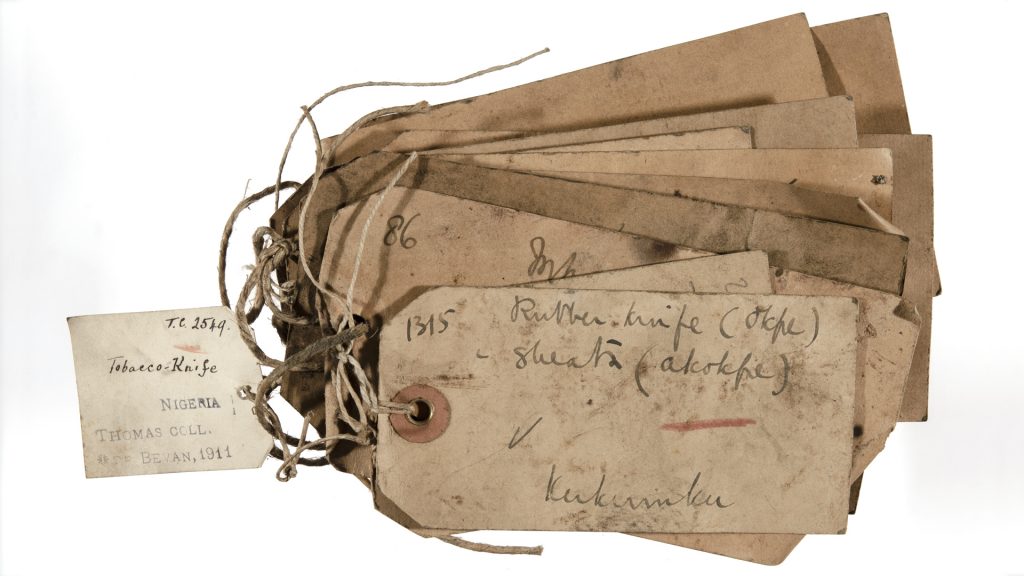

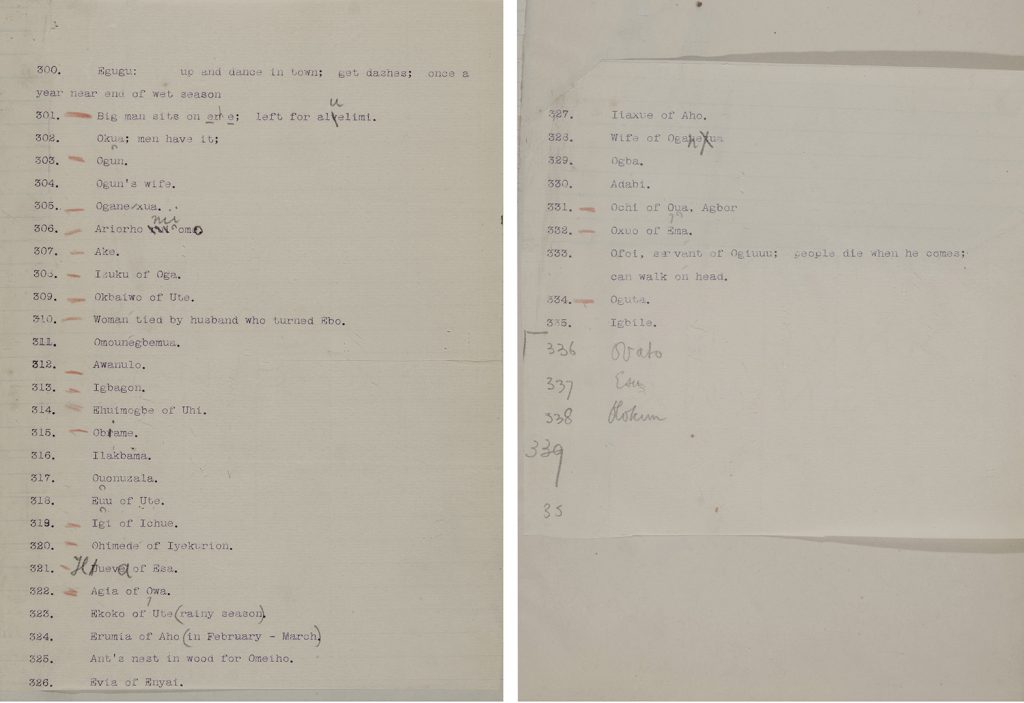

Various different labels have been attached to objects in the so-called ‘Thomas Collection’ at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge. The first of these appears to be have been attached to the objects in West Africa prior to shipment to the UK. These are mostly manila luggage tags. The writing on these card labels is usually in Northcote Thomas’s own hand. They typically include the sequential object number that Thomas used to identify them, a brief description of the object, including phonetic transcription of the name of the object in the local language or dialect, and the location in which the object was collected. The names of locations and ‘tribal’ groups are sometimes used interchangeably, and some of these are now regarded as offensive colonial appellations: Afemai ethnic groups/territories in the north of present-day Edo State are, for example, labelled ‘Kukuruku’; Urhobo groups/territories in present-day Delta State are labelled ‘Sobo’. Only very occasionally have we have identified more extensive field notes made by Thomas about particular objects he collected, so these original labels constitute the main source of information about each item.

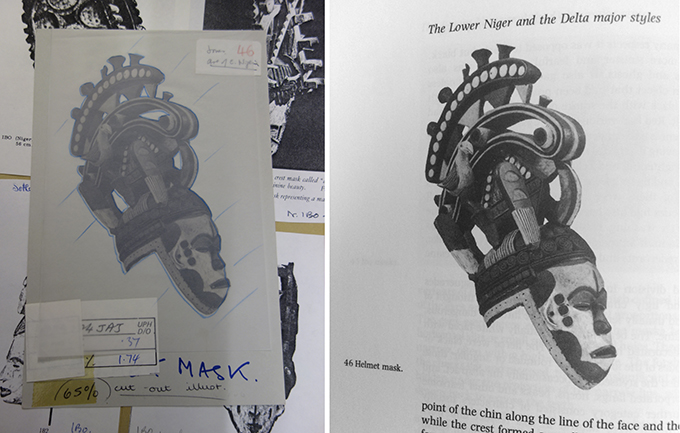

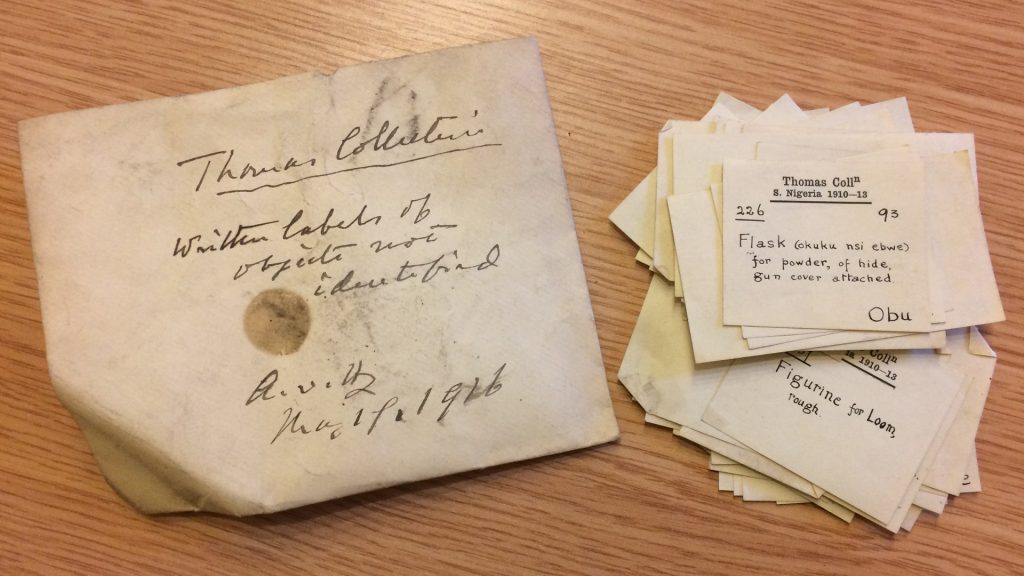

Once the objects arrived at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge, some of the information on the original labels was transferred to catalogue books and new labels were attached to the objects. Sometimes the original labels were left in place, in other cases they were removed. There is, for example, a collection of detached labels associated with objects from Thomas’s 1909-10 survey of Edo-speaking peoples in the Museum’s archive. Pre-printed labels were made for the materials collected during Thomas three tours in Southern Nigeria with the words ‘Thomas Colln | S. Nigeria 1910-13’ printed at the top. Under this printed header, are written: Thomas’s original object number, a Museum accession number, a brief description of the object taken from the original label, and the place of collection. These were either adhered directly onto the objects or stuck on small luggage tags and tied to the objects. For the Sierra Leonean collections, equivalent labels were produced in-house, with ‘Thomas Collection | Sierra Leone 1914’ typed at the top.

It is likely that the work of relabelling the Nigerian collections was started in 1913-14, between Thomas’s third and fourth tours. The 1914 annual report of the University of Cambridge Antiquarian Committee makes mention of Thomas spending a week at the Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, as it was then called, ‘classifying and labelling his collections’. It appears that the relabelling work continued for some time. Evidently labels were prepared for objects from Thomas’s catalogues that could not actually be identified or located in the Museum: an envelope containing such labels survives in the Museum archive. In the curator Baron von Hugel’s hand is written: ‘Thomas Collection | Written labels of objects not identified | A.v.B. 1916’.

In preparation for the [Re:]Entanglements project exhibition at the Museum of Archaeology and Archaeology, we have collaborated with the museum conservation programme at the Institute of Archaeology at University College London (UCL) to conserve objects collected by Northcote Thomas that will be included in the displays. As part of the process, the object labels were also conserved, acknowledging that they are integral parts of the objects’ histories and biographies. One of the students working on the project, Ben Knox, takes up the story …

Conserving Thomas collection labels

by Ben Knox

The way an object is labelled can influence the perceived history and values associated with an item or wider collection. Conversely damage or loss of labels can take away the context of an object.

As a conservation student at UCL I had the pleasure of working on a small selection of objects from the Thomas Collection as part of the Museum Affordances / [Re:]Entanglements project. As well as preparing the objects for exhibition, this work included cleaning, flattening and repairing their historic labels.

As conservators, we attempt to use the minimal amount of materials in treating objects, with the goal of cleaning, repairing and stabilising an object without introducing undue changes or excessive modern materials.

As noted by Paul Basu above, we encountered two types of labels: small paper labels stuck directly to the objects and larger card tags tied on with twine. The small paper labels had come unstuck around the edges, with some buckled and one completely detached from the object. Those with loose edges were re-stuck using a water-based methyl cellulose adhesive.

In the case of one mirror frame that we were working on, collected by Thomas in Okpe in 1909, the paper label had buckled and was lifting away from the surface of the object in the middle. Initial attempts to counter this by introducing a small amount of water vapour to ease the tension in the paper and make it easier to manoeuvre were unsuccessful, so it was decided to fully remove the label from the object, thus allowing flattening and stain removal.

The label was removed with two soft bristle brushes, gently brushing water under the edges and easing it away from the surface of the object. In order to remove the stains and flatten the label water vapour was introduced from under the label, with a dry absorbent layer over top. As the water vapour moved through the label it mobilised some of the dirt, allowing it be drawn away from the surface of the label into the absorbent layer. After the stains were removed, the label was dried under weights to ensure it remained flat before being adhered back to the mirror frame.

The large brown luggage tags presented a different challenge to treat as they were thicker than the small paper labels and ranged from slightly buckled to significantly curled. Most of these include brief notes in either pencil or pen with a number and the object’s cultural group or collection location.

My initial focus for the luggage tags was a label from what Thomas described as an ‘oji onu’ mask, collected in Awgbu (then spelled Obu) in present-day Anambra State, Nigeria. The label had become badly curled, with tears along edges and weak points where the label had been bent. To allow treatment I gently untied the tag from the mask and cleaned minor dirt from the surface of the luggage tag.

After surface cleaning I placed the label in a sealed polyester sheet ‘tent’ with water vapour. This controlled micro-environment allowed the paper fibres to become humidified and relaxed, permitting me to ease the label from its original curled state to a flat state. Once flat the label was placed under weight, ensuring that it did not curl again as it dried.

Once the label had dried flat I repaired any tears in the paper and supported weak parts of the luggage tag. This was done with a small amount of water based adhesive and strips of a special type of tissue paper (conservation-grade kōzo long fibre tissue paper) that gave strength to the repairs.

In the case of a large carved mirror frame that was being conserved, the brown luggage tag had broken completely at one end. Thankfully the detached piece had been saved, preserved with the object in a sealed plastic bag. After initial surface cleaning of the luggage tag I decided not to attempt to remove the tied end of the luggage tag and instead repair the tag in situ. After carefully aligning the two pieces I adhered the two edges together, placed a length of tissue paper over top and brushed adhesive over the tissue paper and onto the luggage tag to give strength to the join. This repair was allowed to dry under weight before the luggage tag was turned over, at which point another piece of tissue paper was placed along the join and adhesive brushed over. Small tears in the luggage tag were also adhered together and backed with tissue paper to support the repairs.

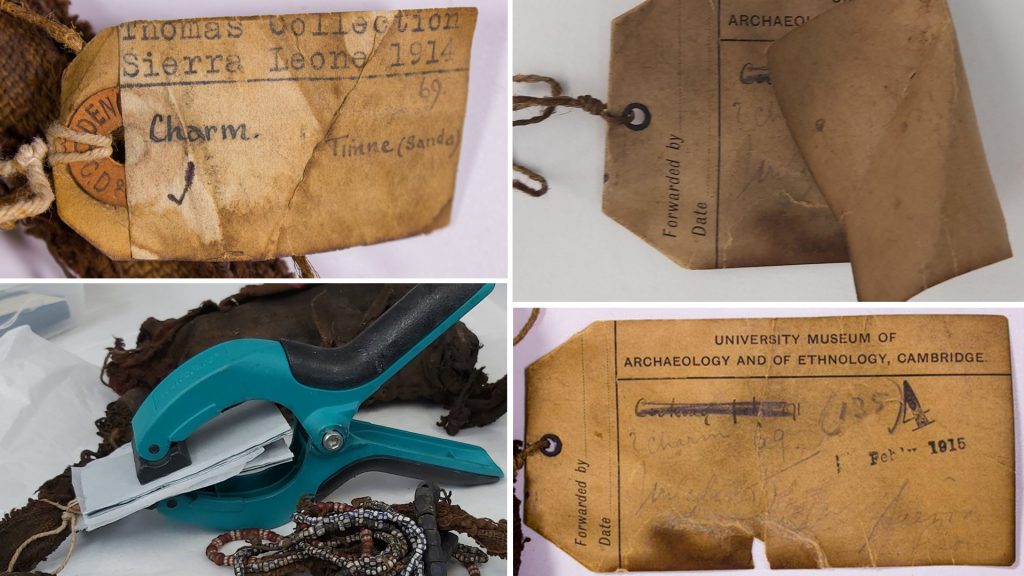

The final object I was able to work on was a charm from Sierra Leone. Two luggage labels were tied to this object: a larger pre-printed Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology tag, and a smaller tag with a paper label stuck on it (those used on Thomas’s Sierra Leone collection). Both were curled, with the larger label cracked and torn in places, while the smaller label was in mostly good condition.

To treat the larger label I initially placed it in a polyester sheet tent with slow release water vapour to gently relax the paper fibres in the label and allow it to be gradually flattened. The label was then dried under weight to ensure it remained flat. Although the detached fragment had been included with the label, there still remained a gap in the long bottom edge of the label. To help support this I adhered the detached fragment to the large label and then backed both the fragment and gap on the label with tissue paper to strengthen the repair. Minor tears and weak points from folding were also adhered and backed with tissue paper to ensure the repairs were supported.

For the smaller label I decided not to remove it from the charm as this may have damaged the string holding it onto the object. Instead, I introduced water vapour to the label by clamping it between archival cardboard and Bondina polyester sheets, with a Gore-Tex barrier layer to stop direct contact between the damp paper and label to avoid saturation. Because this was not dried under weight, the label remained a little curved, but in a more stable and legible state.

As a conservation student it is often daunting to treat historic objects, especially when trialling new treatment approaches. Overall the treatments proved successful, allowing the labels to be more easily read and handled without worry of causing further damage. Perhaps the most effective method was the use of humidification to help flatten the various labels. The gentle and controlled introduction of water vapour, followed by careful flattening and drying, proved to be a very effective treatment for the labels.

It has been a great opportunity to work on these objects from the Thomas Collection and as a student I feel much more confident in treating organic materials, especially works on paper. I would like to give special thanks to conservator Carmen Vida for her support while treating these objects, and all those who are involved in the [Re:]Entangelments project for allowing access to these objects.

Thanks for your great work too, Ben!

![Ukhurhe installation at the [Re:]Entanglements exhibition](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Re-Entanglements_exhibition_Ukhurhe_installation_re-entanglements.net_-1024x576.jpg)

![Ukhurhe installation at the [Re:]Entanglements exhibition](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Re-Entanglements_exhibition_Ukhurhe_installation_2_re-entanglements.net_-1024x683.jpg)