Masquerade traditions are widespread across West Africa. Masked performers are earthly manifestations of spirits – whether of ancestors or forces of nature. They mediate between the visible world of humans and the invisible world of the spirits. They often play important roles in ceremonies marking key rites of passage, such as initiation into adulthood or passing to ancestorhood, and in ritual cycles, for instance those associated with farming, fertility and renewal.

Such spirits may be benevolent tutelary figures; some are fierce and forbidding; others may be clown-like and entertaining. Much has been written about their function in society, their iconography and symbolism, and the dramaturgy of their performances. Earlier European commentators often characterised these figures as ‘festishes’ or ‘juju’. Thomas was among the first to recognize their importance in the wider ‘magico-religious sphere’, and that this was not merely about ‘belief and worship’, but ‘inextricably mixed up with law, social organisation and other elements of human life’. He also acknowledged, however, that not enough was known about them to offer an adequate analysis, not least since this knowledge was largely restricted to initiates.

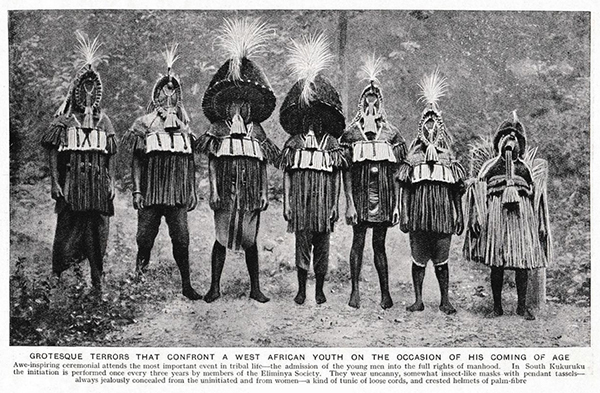

During his anthropological tours in Southern Nigeria and Sierra Leone between 1909 and 1915, Northcote Thomas photographed and documented many different masquerades, from the Eliminia performed by senior age-grade members in Otuo or those associated with annual Ovia festivals around Benin City during his Edo tour, to the graceful maiden spirit (Agbogho mmuo) or aggressive Mgbedike of the Nri-Awka Igbo. Here we focus on Thomas’s photographic documentation of Sierra Leonean masquerades.

Ndoli jowei

‘Indigenous’ Sierra Leonean masquerade traditions are quite distinct from those found in Southern Nigeria and from the Igbo- and Yoruba-derived traditions introduced into Sierra Leone (especially Freetown) by the so-called ‘Liberated Africans’ in the 19th century. Of the indigenous types, only the Ndoli jowei (the ‘dancing sowei’) of the Mende female Sande society is well known. Its distinctive black helmet mask has become a national symbol of Sierra Leone, and examples are to be found in many museums.

Ndoli jowei is just one of a family of Mende spirit manifestations, although it is especially notable since it is one of the few female masquerades actually danced by women (in contrast to the Igbo Agbogho mmuo, for instance, which is a representation of a female spirit, but danced by men). Thomas photographed examples of the Ndoli jowei in Tormah (now known as Tormabum) in present-day Bonthe District, Southern Sierra Leone in 1915. He identified them in his photo register as ‘Bundu devils’, using the name given to them by Christian missionaries, who demonized such spirit manifestations.

‘Bundu’ – or, more correctly, ‘Bondo’ – is the Temne name for the women’s society known as Sande in Mende-speaking areas of Sierra Leone. Although associated with the Mende, the society and its masquerade is in fact more widespread in Sierra Leone, and can be found in many Temne-speaking areas where the Ndoli jowei is known as Nöwo.

Samawa

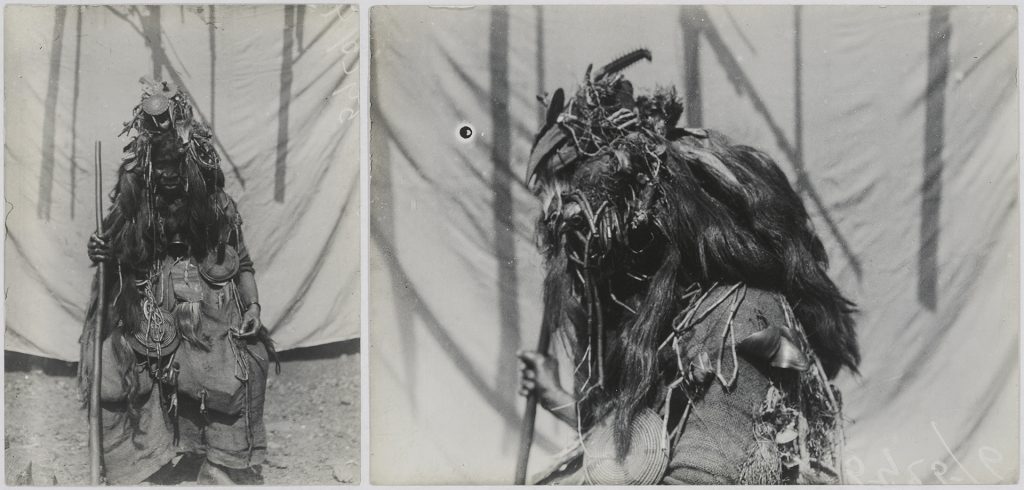

Another photograph relating to the women’s society masquerades was published in Thomas’s Anthropological Report on Sierra Leone, and is also captioned ‘Bundu “Devil”’. This is an altogether more intriguing figure insofar as the costume does not include the familiar black helmet mask. The photograph was taken in the Temne-speaking town of Magbeli (today spelled Magbile or Magbele) on the banks of the Rokel River. In his photographic register, Thomas also provides the name ‘Pa Fore Salia’, and indicates that the photograph is of a woman. It is interesting to note that the woman carries a man’s name and title.

In contrast to the finely carved helmet mask and dyed raffia costume of the Nöwo or Ndoli jowei, this masquerade costume might be best described as an accretion of beads, coiled basket roundels, bones, bells, shells and animal hair attached to sack cloth. The face of the dancer – presumably Pa Fore – is only partially obscured by the headpiece. This corresponds most closely to the Samawa masquerade described by Ruth Phillips in her book Representing Woman: Sande Masquerades of the Mende of Sierra Leone. (If you know the equivalent Temne name for this figure, we would welcome your advice.)

Samawa is a satirist, and her use of humour can be light and playful, but can also border on the menacing and frightening. Phillips’ description of a Samawa she witnessed during her research in Southern Sierra Leone in the 1970s, shares many features of the character photographed by Thomas in Magbile:

The costume and performance of samawa change depending on the specific object of her satire. She wears no headpiece, but rather face paint, exaggerated clothing, and the appropriate appended objects. In one performance of samawa that I saw, the impersonator’s face was painted with black and white spots to represent leprosy, a strip of fur was tied around her chin as a beard, and she was dressed in dirty rags. A big bulge under the front of her costume represented a swelling of the scrotum, and she hobbled about leaning on a stick like a cripple. All these deformities, she sang, would afflict any man who disobeys Sande rules, and she interrupted her song with bursts of loud, raucous laughter. (Phillips 1995: 90)

Sure enough, on the front of the costume of the ‘Bundu devil’ photographed by Thomas in Magbile, one can see two bulging sacks, probably representing elephantiasis of the scrotum, which is indeed a condition that men who dare to intrude on the secret practices of the women’s society are said to contract.

It is perhaps no coincidence that this is one of the few facts about the Bondo society that Thomas records in his Anthropological Report. The threat of scrotal elephantiasis was perhaps sufficient to deter him from pursuing his inquiries further!

Pa Kasi

In contrast to his limited investigations of women’s initiation societies, Thomas conducted extensive research into men’s societies such as Poro and Ragbenle. Thomas attempted to be initiated into Poro at Yonibana, but was prevented from doing so as a result of the intervention of a junior colonial administrator by the name of W. Y. Lyons. When Thomas complained about this interference, it was claimed that Lyons acted in the interests of the local population. It is more likely, however, that the idea of a European acting on behalf of the colonial government being initiated into a West African ‘secret society’ was seen as a transgression of a racialised boundary, which could not be tolerated by the colonial authorities.

When Thomas submitted the initial draft of his Report to the Colonial Office at the conclusion of his Sierra Leonean tour, he requested that many details of the Poro society and its connection with chieftaincy be withheld from publication because they would cause embarrassment to his informants. Due to these ethical concerns, the section on Poro in the published report is quite cursory.

There are many masquerades associated with Poro in the south of Sierra Leone, some of which had been previously photographed and published by the colonial administrator T. J. Alldridge. Thomas’s anthropological survey was focused in the north and central Sierra Leone, and he took relatively few photographs during his travels in the south, none of which include male masquerades. (The relative sparsity of photographs from the latter period of Thomas’s Sierra Leone tour was probably due to difficulties obtaining new glass plate negatives as the First World War intensified and affected shipping to West Africa.)

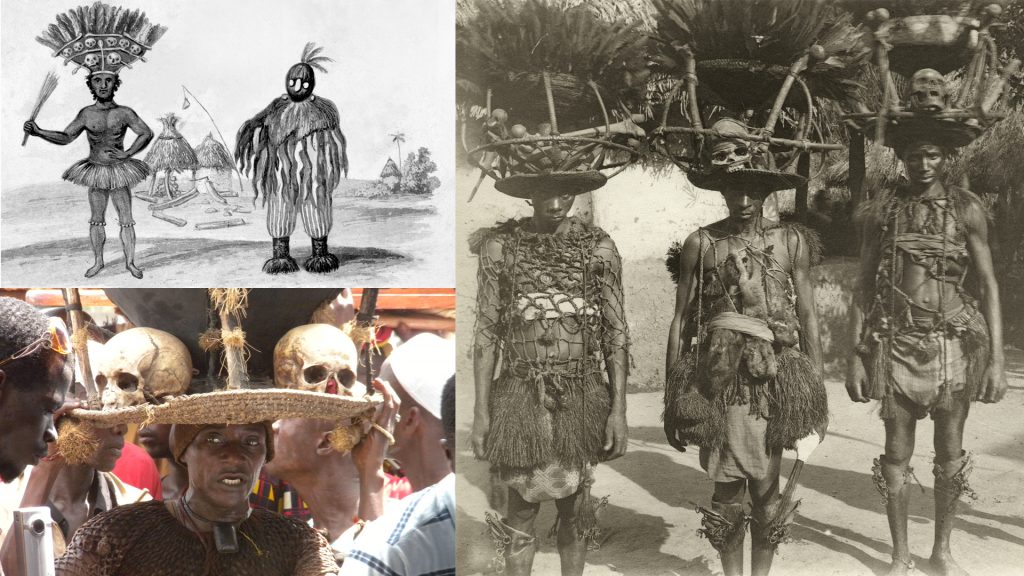

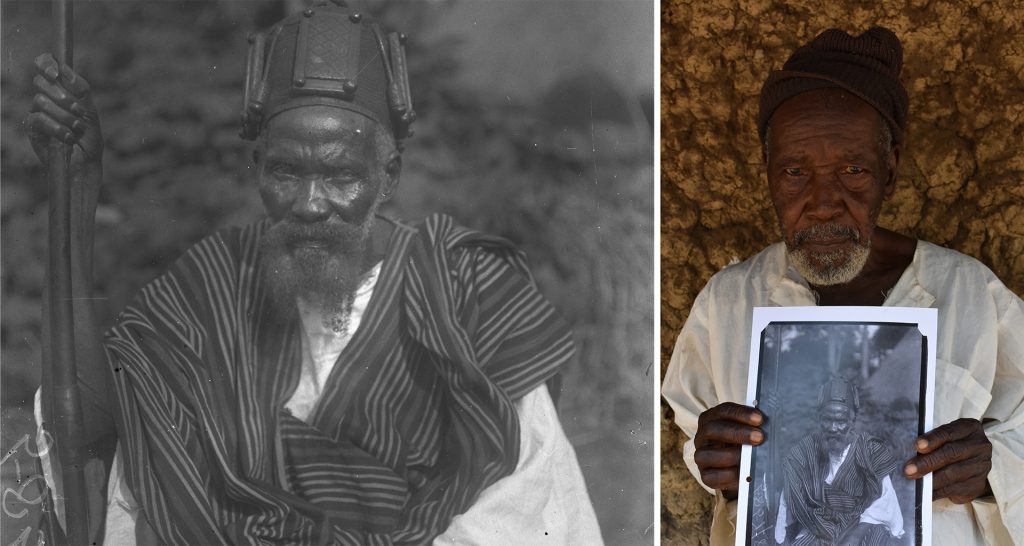

One Poro figure that Thomas did photograph, however, was ‘Pa Kasi’. Pa Kasi is not, strictly-speaking, a masquerade. He is, rather, a senior official of the men’s Poro society. Due to the remarkable nature of his costume, however, we include him here. The photograph was taken in Mabonto in present-day Tonkolili District, Central Sierra Leone. Pa Kasi plays important roles in the initiation of new members into Poro and also the crowning of paramount chiefs. The same figures is known as ‘Tasso’ in Mende-speaking areas. Thomas describes him as a ‘doctor’, adept at controlling the powers of magico-herbal ‘medicines’ which have the ability to both cure and kill.

The most remarkable aspect of Pa Kasi’s costume is his headdress of ambong. This takes the form of an inverted cone with, according to Thomas, the ‘feathers of the greater plantain-eater in it’. Around its rim are arranged skulls and thigh bones. In Thomas’s account, ‘the skulls are said to be those of people who have infringed Poro law’. This accords with the account of the American anthropologist Vernon Dorjahn who conducted research on the Temne Ragbenle and Poro societies in the 1950s and who states that the ‘skeletal material’ on Pa Kasi’s crown was ‘obtained from those executed for breaches of Poro discipline’ (Dorjahn 1961). In his description of the Tassos in Southern Sierra Leone, Alldridge (1901: 131), however, notes that the bones are those of ‘defunct Tassos’, whom the wearer has succeeded in office.

a-Ròng-a-Thoma and Namangkèra

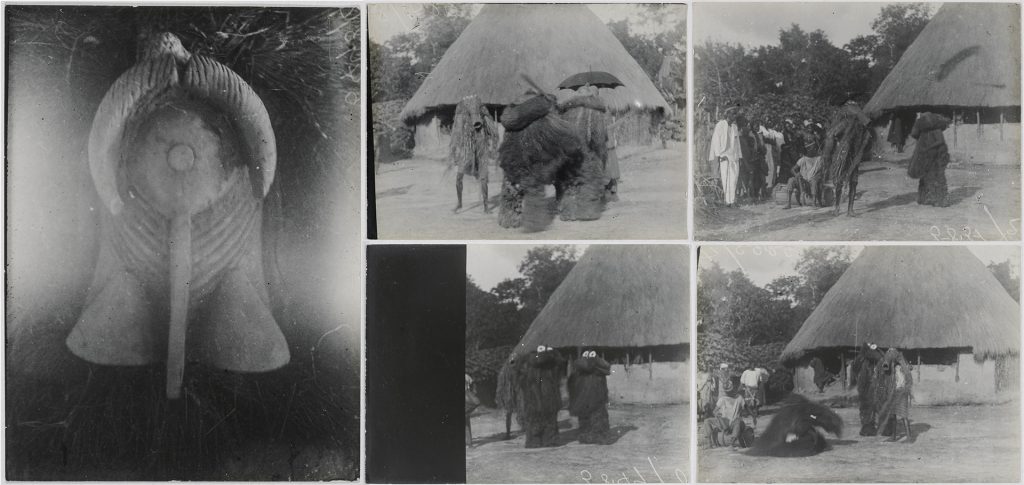

Whereas the Pa Kasi/Tasso figure has been documented by European travellers in Sierra Leone since the 1750s, Thomas was the first outsider to record the a-Ròng-a-Thoma and Namangkèra masquerades of the Temne Ragbènle society. It has been suggested that these spirits – krifi, or kärfi, in Temne – are found exclusively in Yele in Gbonkolenken chiefdom, in Tonkolili District, Central Sierra Leone, and that they travel to other chiefdoms in the region to perform at the crowning of chiefs. Thomas makes no reference to a-Ròng-a-Thoma and Namangkèra being exclusive to Yele, however, and, indeed, he photographed examples in Matotaka and Mamaka, in present-day Tane and Yoni cheifdoms respectively, which neighbour Gbonkolenken in Tonkolili District. Our own research also suggests that they continue to exist outside of Yele in other chiefdoms where the Ragbènle society is found.

Thomas’s Anthropological Report on Sierra Leone contains just a few notes on a-Ròng-a-Thoma and Namangkèra. Thomas documented, for example, the Ragbènle society’s role at the death of a chief and the initiation of a new chief. At each of these occasions, and also on the death of a member of the society, the a-Ròng-a-Thoma comes out to perform. a-Ròng may be glossed as meaning ‘mask’, and, according to Thomas, Thoma or Toma means ‘forbidden’, but is also the name of a particular tree. The wood of this tree, he notes, cannot be placed on a fire by a member of Ragbènle or he will burn himself. a-Ròng-a-Thoma generally dance in pairs and are accompanied by Namangkèra, who is a messenger figure.

Although there are a number of a-Ròng-a-Thoma headdresses in museum collections, until recently Thomas’s photographs were until recently the only documentation of the spirits in their complete costumes. The art historian, Fred Lamp, made a study of the figures during his fieldwork in Yele in 1979-80, during which he interviewed the paramount chief, officials of Ragbènle and former dancers of a-Ròng-a-Thoma. Lamp records that è-Ròng-è-Thoma are said to be the ‘chiefs’ of all the Ragbènle spirits, while Namangkèra is their brother. Both are regarded as water spirits. The wooden a-Ròng-a-Thoma mask is zoomorphic in form, with wide, flaring nostrils, a grid of teeth, and a pair of horns that curve around the crown of the head. It is worn with a costume of dyed raffia. According to Lamp, they are considered responsible for the general welfare and safety of the community and the growth of crops. Namangkèra’s mask has a conical, funnel-like opening, which Thomas describes as a ‘long wooden beard’ (the example photographed by Thomas has more anthromorphic facial features). Lamp notes that unlike a-Ròng-a-Thoma, ‘Namangkèra makes sounds and is very talkative, argumentative to the point that people describe him as a “lawyer”’.

Sankoh

A particularly unusual type of masquerade figure that Thomas photographed, and which is unique in Sierra Leone in having a brass face, is the a-Ròng-a-Rabai – the ‘mask of chieftaincy’ – or what Thomas refers to as the ‘cheifship krifi’. These are found exclusively in Temne areas of Sierra Leone, and have very rarely been documented. In an article on such masks, Bill Hart states that these are usually bear the name of the chiefly clan, often in archaic form. In his Anthropological Report, Thomas provides a more detailed account of the ‘cheifship krifi’ that he encountered at Mamaka. He writes,

At Mamaka he is called Sanko; Sanko and the chief, Satimaka, must be in separate houses; like the chief, he may not go where bundu [i.e. the women’s society] implements are kept, nor where there is a new-born child. It is significant that at the chief’s death his Sanko retires and is replaced by another man after offering a sacrifice.

Sanko wears a helmet of leather surmounted by a tuft; the face is of brass and there is a brass plate behind; strips of leopard skin are attached to the base, and over the skin is fibre that reaches to the waist. He has fibre ruffles round his wrists and net anklets with fibre tops. Four sticks tied together (bonkoloma) are in his hand; they are the chief’s staff; in point of fact the staff actually used by the chief is quite different, long and forked at the top.

The chiefship mask of Magbile is known as aron arabai; like Sanko the wearer cannot come out when the chief is dead; the mask is kept in the chief’s house. The dress is formed of skins, and he has palm-fibre trousers.

When he goes for a walk through the land he carries a broom and whips to flog people who do not come out when he dances. He can judge cases and pay the money received to the chief.

When we did fieldwork in Mamaka as part of the [Re:]Entanglements project, we were careful to discuss with the senior men the fact that we had photographs of things that perhaps not everyone was permitted to see. Among the elders we met was Pa Amadu Kamara, the grandson of Chief Satimaka, whom Thomas photographed. We learned Pa Amadu’s grandfather’s full name was Satimaka Memneh Sankoh, and that Sankoh is the name of the ‘devil’ (i.e. spirit) that dwells in the hill above the town. The devil of the hill, we were told, has someone in the town who is called Pa Sankoh. Pa Amadu expressed surprise that Thomas was able to photograph Sankoh; neither did he know whether the spirit still dwelled in the hill. There seemed to be a distinction made between the spirit or krifi, Sankoh, after whom the hill was named, and Pa Sankoh, who alone could communicate between krifi and the people of the town.

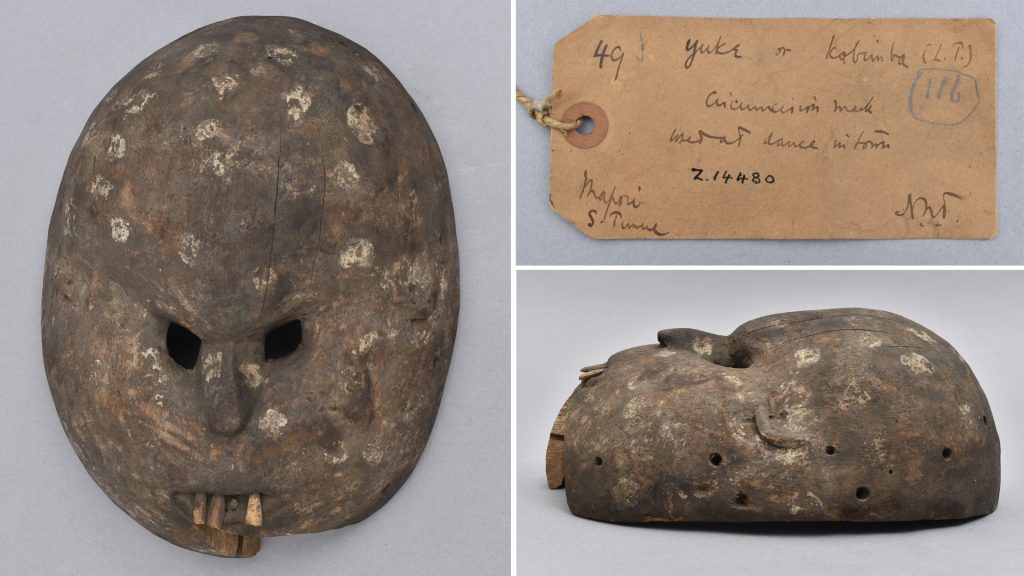

Ayuke or Kabemba

Boys and young men must be circumcised before they can be initiated into the Poro or Ragbènle societies. At the time of the circumcision ceremonies, the initiands withdraw into a circumcision bush, which is forbidden to women and where various prohibitions pertain. According to Thomas’s account of the process, while undergoing the ordeal, those being circumcised are under the guardianship of an old man, and also an old widow who is known as Yabemba. Yabemba must be past child-bearing age, and is the only woman permitted to enter the circumcision bush.

Once the initiands’ wounds have healed, they follow a masked figure – known as Bemba, Kabemba or Ayuke – back into the town, where they dance all night wearing long gowns (runku). Thomas records that in some towns the mask is worn by the man who conducts the circumcision operation (ayunkoli).

Following the ceremonies, Thomas states that the circumcision mask and its raffia costume are generally kept; although he notes that in some places they are thrown into the bush, presumably to decay. Thomas photographed examples of the Kabemba mask in Mamaka, Matotaka and Mayoso, and he also collected one in Mapori (Mafori?), with its fibre and palm-leaf dress, which he notes in his Report is ‘now in the Cambridge Museum of Ethnology’. We were able to identify and photograph this mask during our research with the Thomas collections at the museum, now called the Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology.

Further reading

- Alldridge, T. J. (1901) The Sherbro and Its Hinterland. London: Macmillan.

- Dorjahn, V. R. (1961) ‘The Initiation of Temne Poro Officials’, Man 61: 36-40.

- Hart, W. A. (1986) ‘Aron Aarabai: The Temne Mask of Chieftaincy’, African Arts 19(2): 41-45+91.

- Lamp, F. J. (2005) ‘The Royal Horned Hippopotamus of the Keita of Temne: “A-Rong-a-Thoma”‘, Yale University Art Gallery Bulletin: 36-53.

- Phillips, R. B. (1995) Representing Woman: Sande Masquerades of the Mende of Sierra Leone. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History.

- Thomas, N. W. (1916) Anthropological Report on Sierra Leone, Part 1: Law and Custom. London: Harrison & Sons.

![Ikenna Onwuegbuna [Re:]Entangled Traditions exhibition University of Nigeria, Nsukka](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Ikenna_Onwuegbuna_Re-entangled_Traditions_exhibition_Nsukka_re-entanglements.net_-1024x576.jpg)