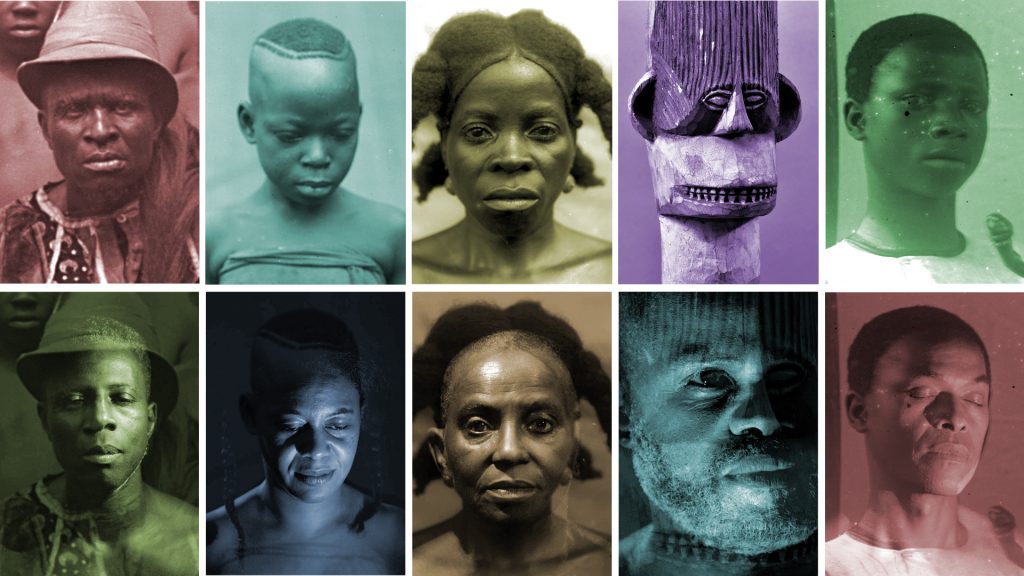

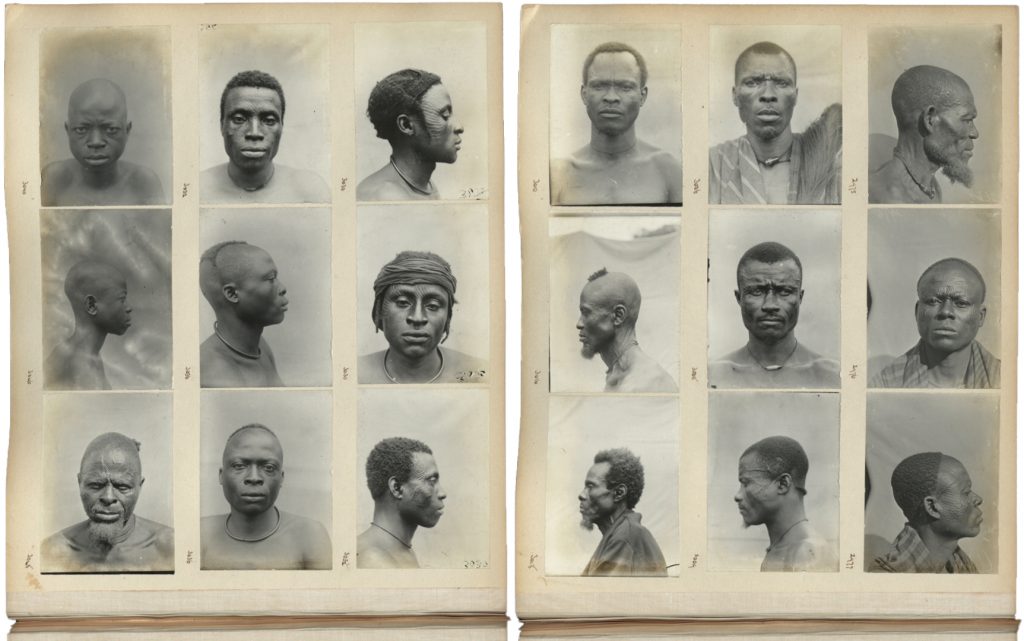

Between 1909 and 1915, during four ethnographic surveys in West Africa, the colonial anthropologist N. W. Thomas and his assistants made over 7,500 photographs. Approximately half of these were so-called ‘physical type’ portraits: head and shoulder shots intended to document the physiological characteristics of different ethno-linguistic groups. Thomas also made hundreds of sound recordings of songs, stories, ‘linguistic specimens’ and conversations.

To date, from this mass of archival photographs and sound recordings, we have only been able to identify one recording of a first person narrative by an individual who Thomas also photographed. This is a speech given by Onyeso, the son of Eze Nri Ènweleána, the spiritual head of the Igbo Nri Kingdom in the second half of the 19th century. In fact, only the published transcript of Onyeso’s speech survives. Onyeso’s speech provides a remarkable insight into the experience of colonialism from the perspective of the displaced ritual and political elite. In elliptical terms, Onyeso refers to the havoc wreaked by colonial intrusion into the Igbo cosmological order of things: Oge ụwa Gọọmentị bịara , anyị wee lee, obodo mebie, he says (‘When the Government came, we looked, and the town was spoiled’).

What, we wondered, if Thomas had recorded the first person narratives of the hundreds of other individuals that were photographed? What other perspectives on colonialism would they have voiced? What stories would they have told of themselves and their experiences? What might they have said about their encounter with the colonial anthropologist, his camera and his phonograph recorder?

The Haitian historian Michel-Rolph Trouillot has written about silences in the archive and in the production of histories. Certain voices – usually the voices of the powerful – are privileged in the historical record, while others are excluded (even if they are visually present, as in Thomas’s ‘voiceless’ physical type photographs). It comes as no surprise that the account of West African societies produced during Thomas’s anthropological tours privileges the authorial voice of Thomas himself. This makes the inclusion in his published report of Onyeso’s speech, with its anti-colonial sentiment, all the more interesting, complicating the assumption that Thomas merely represented a narrow colonialist viewpoint.

Drawing on decolonial thought regarding presencing silenced voices in the colonial archive, and ideas of ‘speculative history’, we worked with the Sierra Leonean storyteller Usifu Jalloh and other storytellers with Sierra Leonean or Nigerian heritage to imagine the stories other individuals photographed by Thomas might have voiced had they been recorded. Five short monologues were developed collaboratively with the storytellers based on archival research but also by ‘listening’ to the photographs of the individuals, as proposed by Tina Campt in her book Listening to Images.

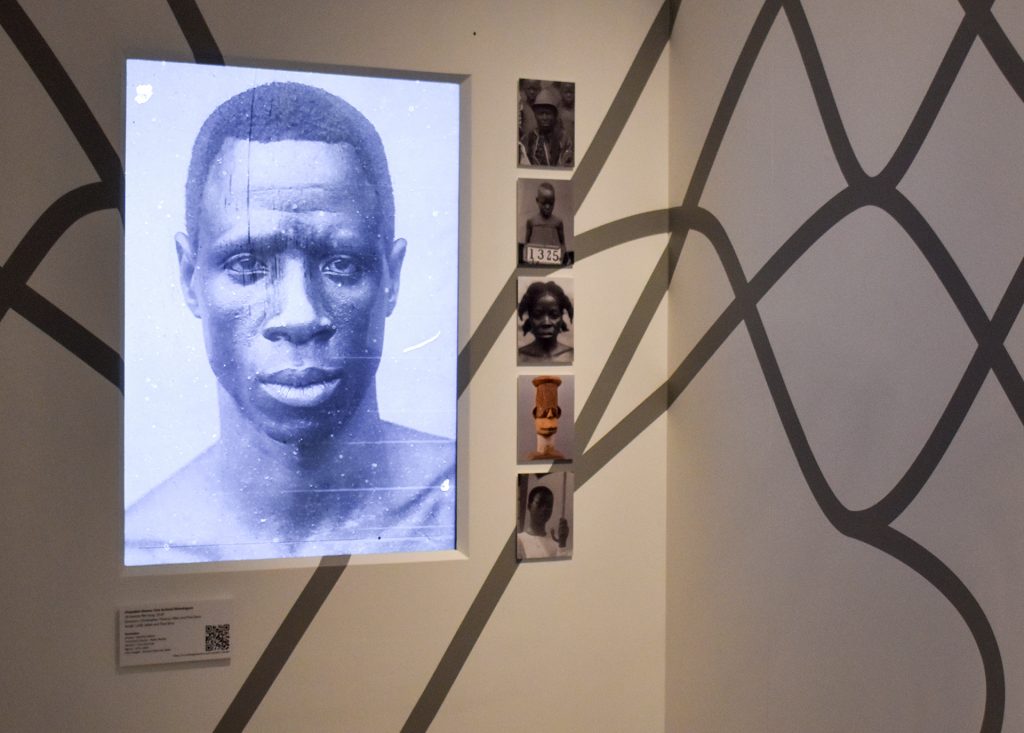

We collaborated with multimedia artist Chris Thomas Allen of The Light Surgeons, to create a video installation of the monologues for the [Re:]Entanglements exhibition. The monologues were filmed in portrait aspect ratio to reflect the framing of the physical type portraits. Between each of the storytellers’ performances, we intercut and morphed between more of the archival photographs to communicate a sense that these were just five from among many hundreds of untold stories, and that each person photographed had their own story to tell. The films’ soundscapes are drawn from the wax cylinder recordings made during the anthropological surveys.

The monologues are, of course, works of imagination. They are also recorded in the English language, whereas Thomas’s interlocutors would have spoken in various dialects of Igbo, Edo and other West African languages. We hope, however, to voice another kind of truth in these characters’ words. As Usifu Jalloh notes: ‘as a storyteller, I live in a world of magic; and in a world of magic, everything is possible!’

Below, you will find videos of the five short monologues, followed by comments by Usifu Jalloh on each of the characters, and discussion of the archival sources that informed our scripts. The article concludes with Usifu Jalloh’s more general comments on bringing the archive to life through storytelling.

Monologue 1: Onyeso

Performed by Olusola Adebiyi

Although the text of Onyeso’s speech was published in Thomas’s Anthropological Report on the Ibo-speaking Peoples of Nigeria in 1913, we wanted to include this as one of the monologues for a number of reasons. As mentioned previously, Onyeso’s is the only first person narrative actually given by an individual who Thomas also photographed and named. Since the original recording has not survived, we wanted to re-enact the speech and bring Onyeso’s words to life.

Onyeso’s father was one of the most powerful people in the Igbo world: a ‘spiritual potentate’ of the Igbo people. When a person assumes the role of Eze Nri, he dies as a mortal human and is reborn as a deity-king. In doing so, he becomes subject to many ritual prohibitions. Traditionally, the Eze Nri cannot leave the town of Nri, and should not be seen by ordinary people. An Eze Nri does not die, but ‘goes travelling’ for a number of years before a new Eze Nri is appointed through the agency of the spirits/gods. In the interregnum between Ènweleána’s reign and that of Obalike, the Eze Nri when Northcote Thomas visited the town, Onyeso acted as Regent. He remained a powerful and influential man at the time of Thomas’s surveys in 1910-11. He had many wives and children.

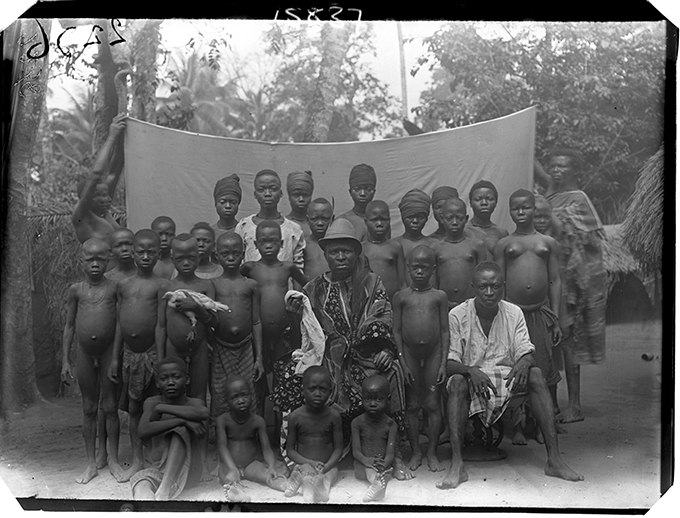

There are at least two photographs of Onyeso in the archive. One of these shows Onyeso surrounded by his children (no fewer than 26 of them!). He wears a highly decorated gown and a European hat with the eagle feathers of his chiefly office tucked into its band. A horsetail flywhisk is laid across his shoulder – another symbol of his titled status. In his right hand, he holds a cloth, the significance of which is not clear. On his forehead we can discern ichi scarification marks.

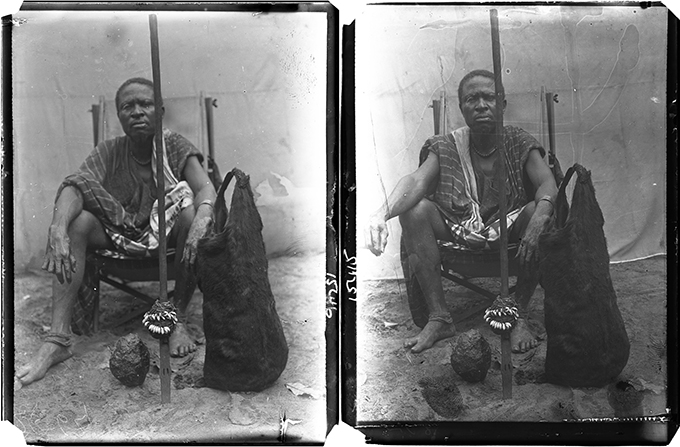

In a second photograph, Onyeso is seated alone on a folding deckchair (perhaps Thomas’s). His right eyelid is marked with nzu, sacred chalk. Around his ankles are akarị; anklets which again show that Onyeso has attained the ozo title. Arranged before Onyeso, besides his goat-skin bag, are two ritually significant objects: his oton and ofo.

In his speech, Onyeso states that he received ichi marks as a baby before he cut his first teeth. He explains that the son of an Eze Nri cuts his teeth by the time he is fourteen weeks old, and that it is necessary for the child to be given the ichi marks before this. Had his teeth come through before he received the marks, this would be considered an abomination according to traditional Igbo cosmology and the child would, in Onyeso’s words, be ‘thrown away’.

Onyeso goes on to talk about the role of the Eze Nri’s sons in maintaining social order. He reminds his audience that it is they who are ‘the wearers of the leopard skins’; they who have the authority to settle disputes, not the colonial government. He speaks of the traditional Nri hegemony that has been usurped by the British. This is not just a matter of political authority, but Nri’s role in maintaining the cosmological order. Through Nri control of ritual power, the land is ‘made good’. It is this order that has broken down through the coming of ‘the Government’. There is a suggestion that the Igbo people have willingly accepted colonial authority, perhaps as a way of freeing themselves from Nri’s power over them.

Onyeso stands for the traditional patriarchal and ritual order, which has been shattered by the coming of the Europeans. He speaks defiantly of this into the phonograph recorder of the colonial anthropologist.

See also It is I who come, Onyeso!

Monologue 2: Unnamed children

Performed by Nadia Maddy

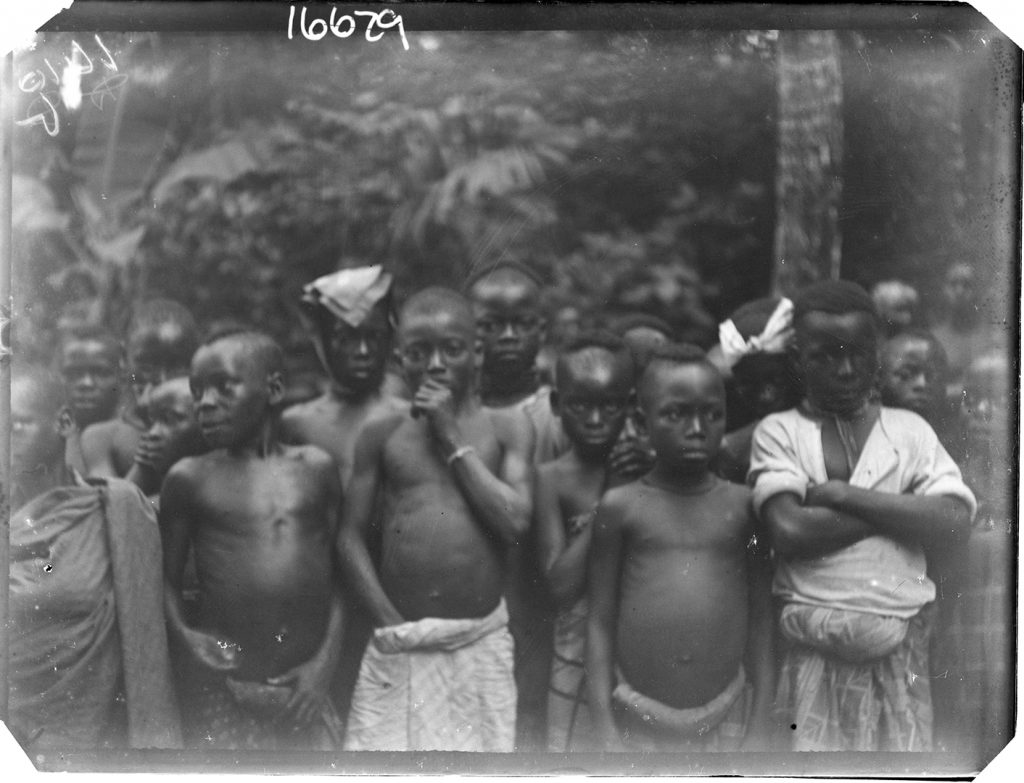

As well as adult men and women, Thomas photographed many children during his surveys. We wondered how they might have experienced the anthropologist’s visit to their town or village. What did they make of this strange white man, who spoke with a funny voice in a mysterious language through intermediaries. What did they make of all the boxes and crates that his carriers and assistants brought with them: a box with a glass eye on legs that he crouched behind (the camera), another box with a wide mouth, into which people were asked to speak (the phonograph). What rumours might have passed between the children about these things? The white man was capturing people’s faces, capturing their voices. What was he doing with them? Where was he taking them?

In the photographs, some children seem to avert their eyes from the camera’s lens; others gaze open-eyed, partly in curiosity, partly in fear; some hide behind their older siblings. Had they been told by their parents to do as the white man instructed? Would they be punished if they did not comply?

Unlike the other four monologues, we imagined this as a story as a conversation between different children as they exchanged views about what they had seen and heard. We used names recorded by Thomas or his assistants during the 1909-10 Edo tour. The children relate the views of adults they have overheard: that the white man is a trickster, like Egui the tortoise in traditional Edo stories. They also relate how their elders have outwitted the oyibo: how one man gave misinformation about his name, how the blacksmith over-charged the white man for tools he had been asked to make for his collection.

We also did not want to over-state the impact of the colonial anthropologist’s visit in the communities he worked. His presence would have been fleeting, and no doubt the children had other chores to perform or games to play. His visit may have soon been forgotten.

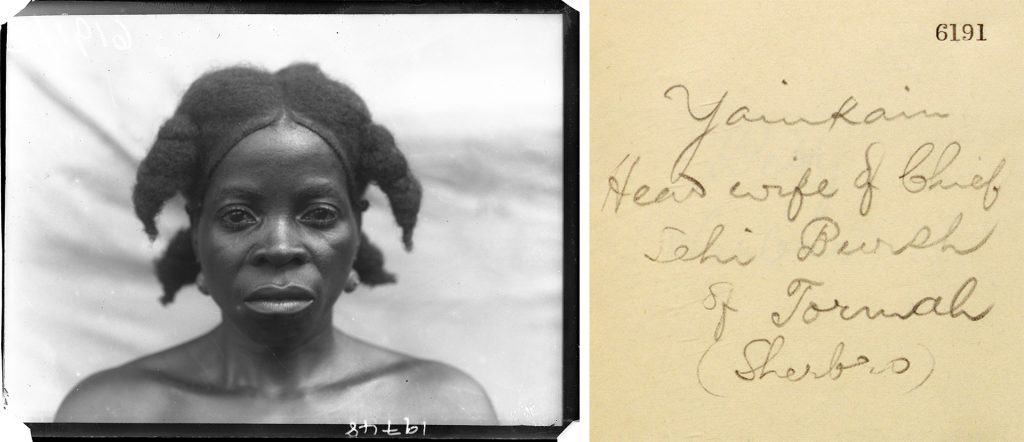

Monologue 3: Yainkain

Performed by Anni Domingo

Men’s voices and perspectives dominate in the colonial ethnographic archive. We wanted to challenge the white, male gaze of the anthropologist with a strong female response. One of the most powerful photographic portraits in the archive is that of Yainkain. Described in Thomas’s photo register (in the handwriting of one of Thomas’s assistants) as ‘Head wife of Chief Sehi Bureh of Tormah’, Yainkain gazes defiantly to camera. Chief Sehi Bureh was not, of course, defined by his wife in Thomas’s notes, and, when we ‘listen to’ this image, we are certain that Yainkain was in no way defined by her husband, even if he was the paramount chief!

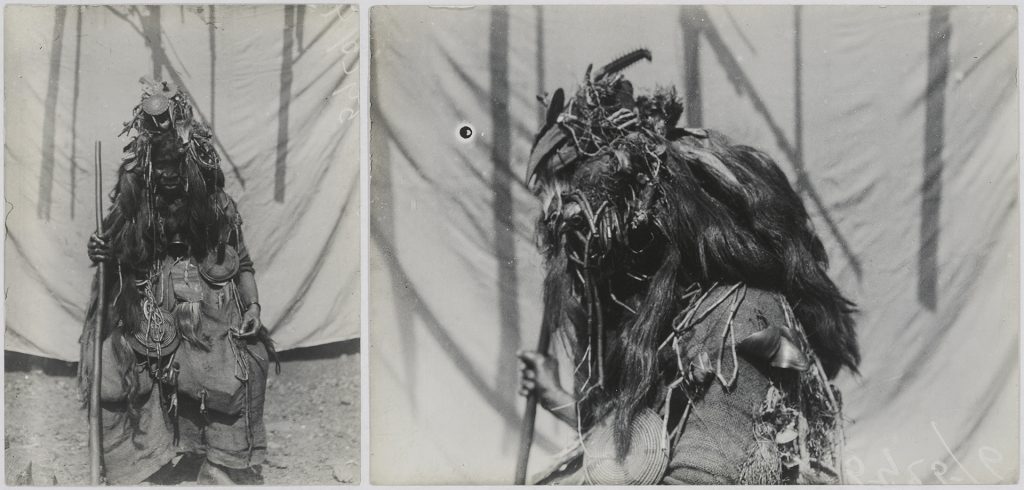

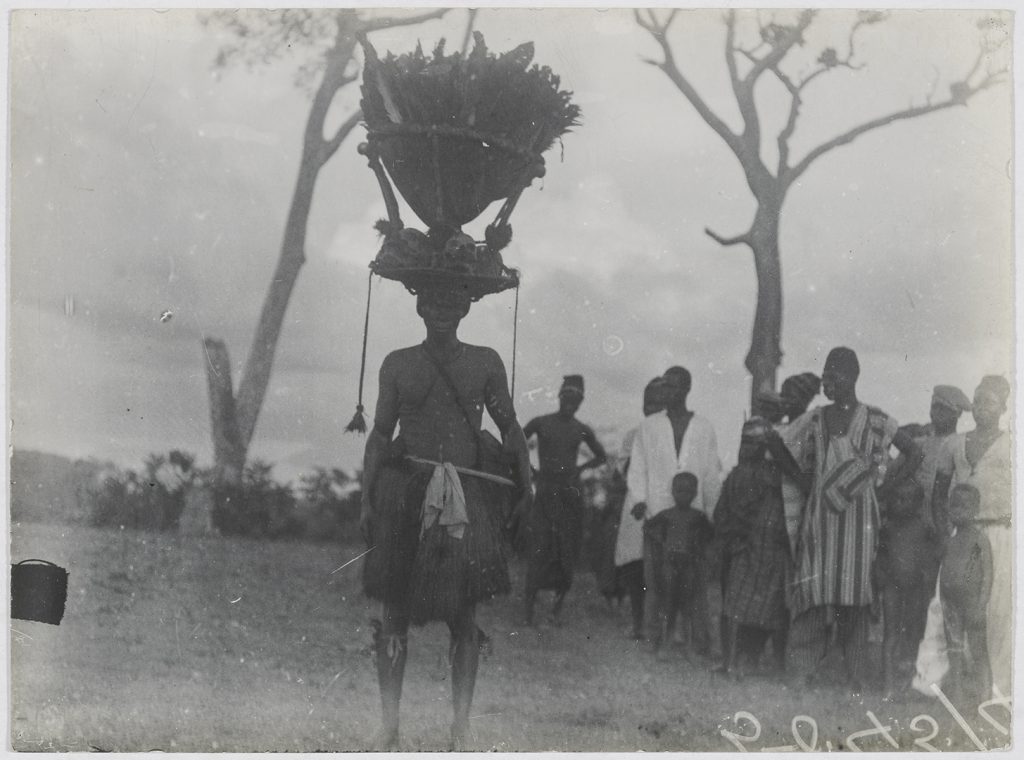

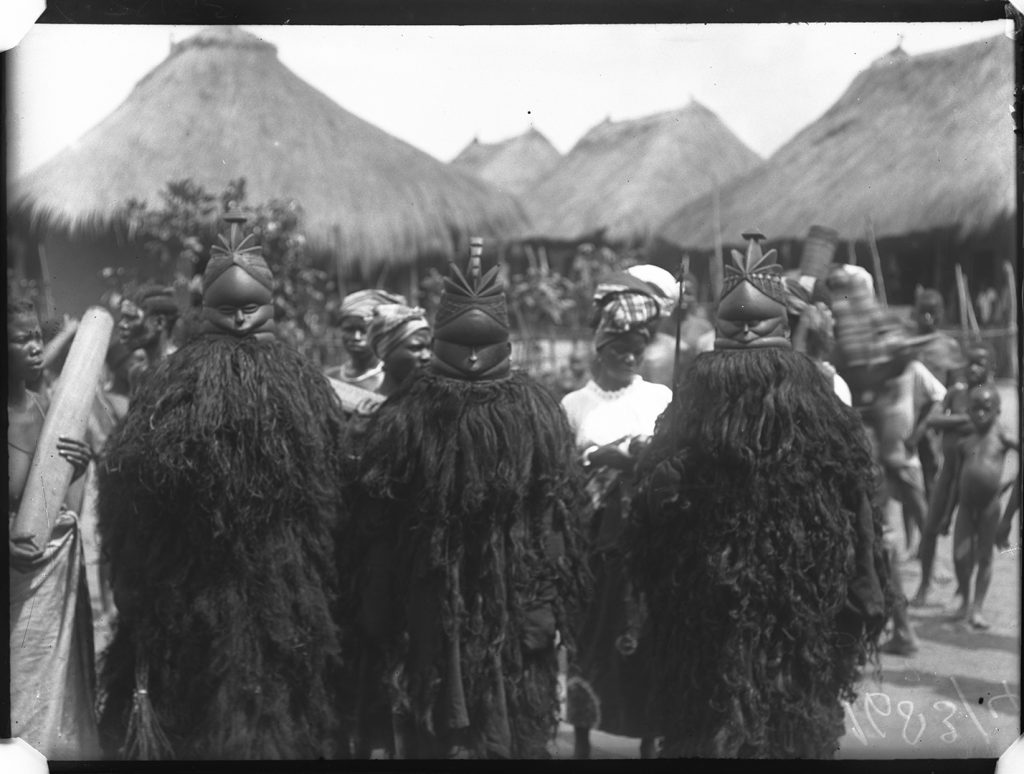

Yainkain’s hairstyle is similar to that reproduced on the carved heads of the female masquerade, the ndoli jowei or ‘dancing sowei’. The masquerade of the female Bondo society is one of the few female masquerades in Africa that is actually danced by women (others represent female spirits, but are danced by men). The ndoli jowei represents ideals of feminine beauty – the smooth, polished black surface signifies health and beauty. Yainkain personifies the Bondo spirit, while the Bondo spirit is a symbol of female qualities and power.

The Bondo society is an important female counterpart to the male Poro society, and keeps male power in check. Thomas writes quite a lot about the Poro society in his Anthropological Report on Sierra Leone, but he barely mentions the Bondo society. Indeed, he would have struggled to get information from the women. Perhaps Yainkain and other members of the Bondo sisterhood were proud of the fact that, while the men gave away their secrets, the women kept their knowledge to themselves. (Thomas attempted to get initiated into the Poro society, but was stopped due to the interference of the colonial authorities.)

See also Sierra Leone masquerades.

Monologue 4: Ngene

Performed by Usifu Jalloh

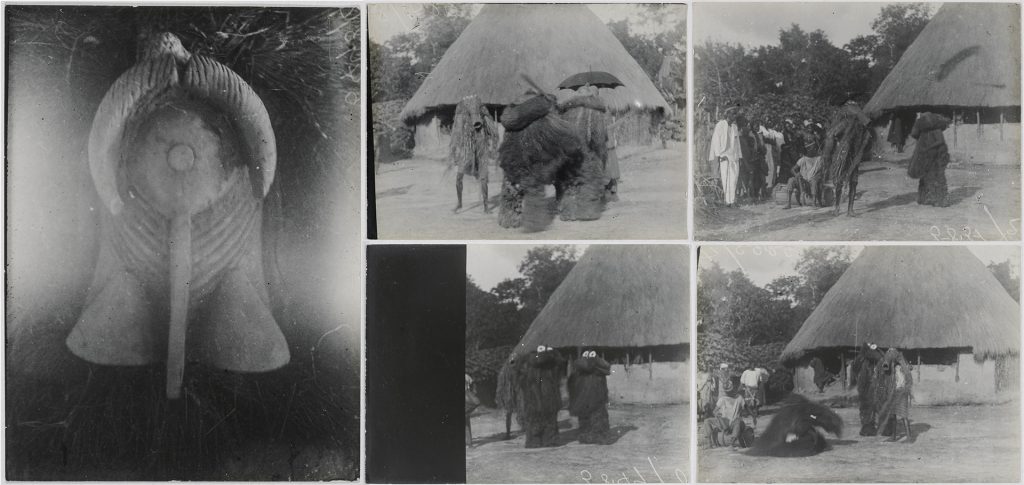

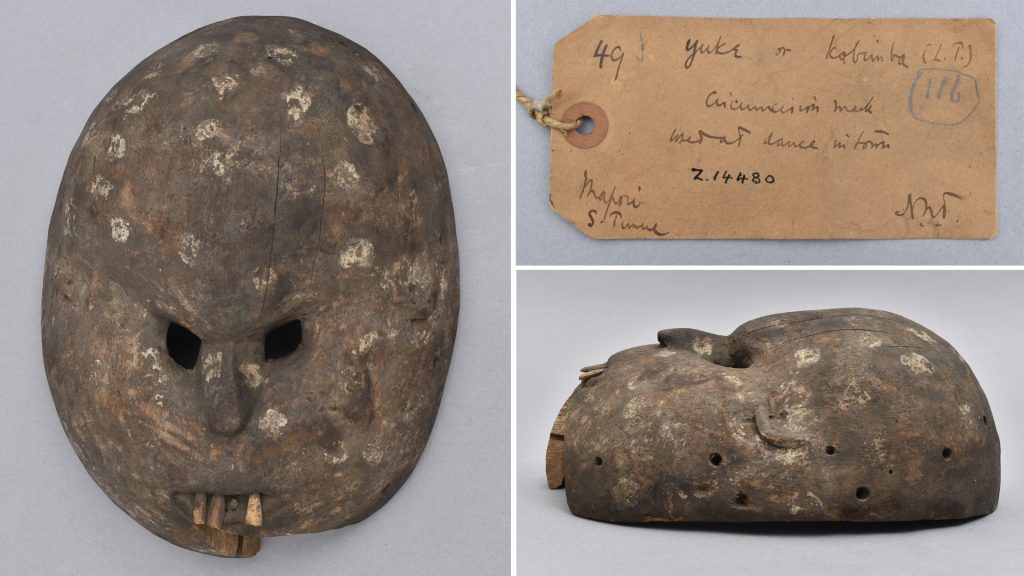

Ngene is a shrine figure, a representation or manifestation of the Igbo alusi (deity or spirit) Ngene. One would communicate with Ngene through a priest of the shrine or dibia (diviner/doctor). Sacrifices must be made. One must greet Ngene first with an offering of kola nut and alcoholic spirits. Ngene is regarded as a good spirit, but he can cause trouble if upset – for instance by building or trespassing on his land without gaining his permission. The Ngene shrine would be within a large enclosure, surrounded by mud walls decorated with uli murals. Ngene himself is painted in white and yellow ochre; he wears the ichi marks on his forehead.

Ngene tells the story of sacred gods turned into secular objects in the ethnographic museum. He represents many of the things collected by Northcote Thomas, and others like him, from Africa and now incarcerated in museums. Instead of a revered and powerful god, he is treated as a thing – a piece of shaped and painted wood that comes to stand for the ‘primitive religion’ of the local people, or a specimen of African art.

Ngene was acquired by Thomas in Awgbu, present-day Anambra State, Nigeria. A label was strung around his neck, carrying the obscure description ‘Ngene. Alusi. To keep alive’. The number ‘378’ was scribbled on the back of his leg. He was crated up with other artefacts, carried over land to the port, shipped as a piece of cargo on the Elder Dempster line to Liverpool, transported by railway to Cambridge and carted into the museum store room.

For over a century Ngene has lain in a coffin-like crate, rarely seeing the light of day. A ‘dead’ museum object. The paradox is that his incarceration has ensured the physical survival of his carved representation – had he been placed in a shrine in Awgbu, the insects would have eaten him and the weather rotted him. Perhaps he would have been burned like so many of his spirit family by iconoclastic converts to Christianity.

As part of the [Re:]Entanglements project, we have set Ngene free (for the time being at least). Removed from his crate, he stands upright and is placed on a strange new shrine – a plinth in the museum gallery. What is he now? Part of the ethnographic archive? An African art object? Or, indeed, is he a god once again? The star of the show? A deity to dance before?

See also Collections notes: Ngene alusi figure

Monologue 5: John Osagbo

Performed by Richard Olatunde Baker

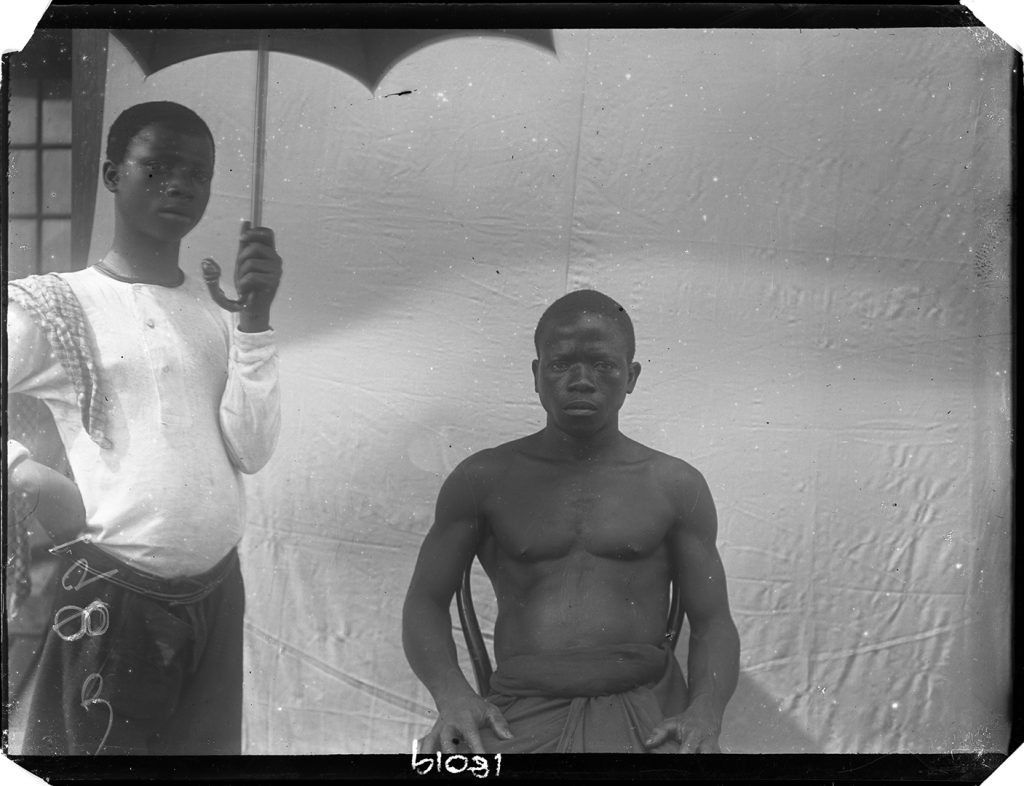

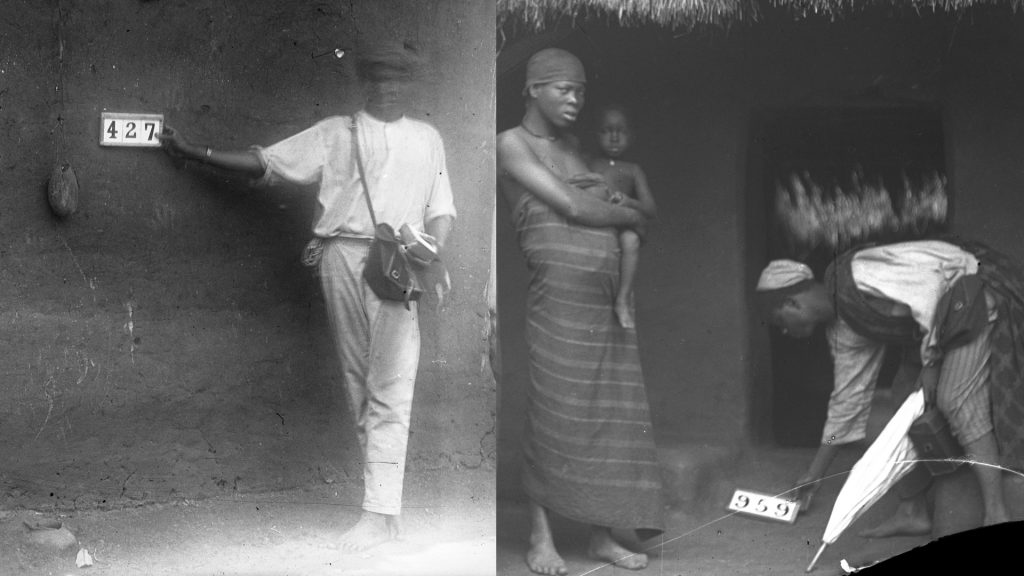

John Osagbo was employed by Northcote Thomas on his first anthropological survey, which focused on Edo-speaking areas of Nigeria (present-day Edo and Delta States). John accompanied Thomas on his travels. Thomas sometimes refers to him as his ‘boy’, his ‘servant’ or his ‘assistant’. He can occasionally be seen at the edge of the frame in Thomas’s photographs, holding an umbrella to shade the sitters, holding a number board, or supporting the photographic backdrop. Thomas also recorded John playing a flute.

Although John was not Thomas’s official translator, the anthropologist probably relied on him for informal translations and help understanding what was going on. In return Thomas probably taught John how to use a camera and operate the phonograph sound recorder.

We don’t know how John came to work with Northcote Thomas, but it must have been a remarkable experience. He would have travelled extensively throughout the Edo-speaking territories of Southern Nigeria as part of Thomas’s retinue. As Thomas’s ‘boy’ or ‘servant’, he was probably intimately familiar with Thomas’s personal habits and quirks. The photographs show that he dressed in European clothes, though went barefoot. We might imagine him being plucked out of his ordinary life in Benin City and finding himself part of the world of the colonialists.

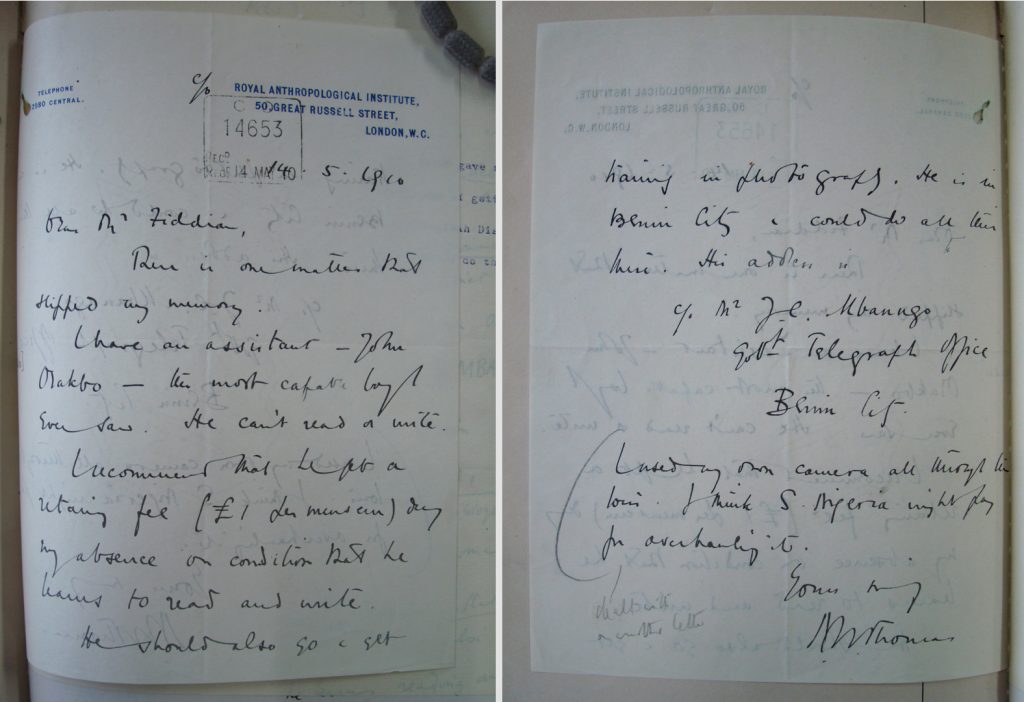

At the end of the 1909-10 survey, Thomas sent a letter to Alexander Fiddian at the Colonial Office in London expressing his appreciation of John – Thomas describes him as ‘the most capable boy I ever saw’ – and asking that he be paid a retainer of £1 a month, on condition that he learns to read and write. He also suggests that he receive training in photography, which, he notes, can be done in Benin City. His address in Benin City is given as care of Mr J. C. Mbanugo at the Government Telegraph Office in Benin City.

We do not know if Thomas’s requests were acted upon. There is no mention of John in Thomas’s subsequent tours in Igbo-speaking areas of Nigeria. We don’t know what happened to him. Did he learn to read and write? Did he receive formal training in photography? Perhaps he became a photographer, or went on to work for the colonial administration? Or were Thomas’s promises empty ones? Did he return to obscurity, forever recalling his year as the anthropologist’s assistant? We might imagine him as an elderly man, in the 1970s, telling stories about his youthful escapades with Mr Northcote – maybe his grandchildren’s eyes rolled at hearing the stories told again and again!

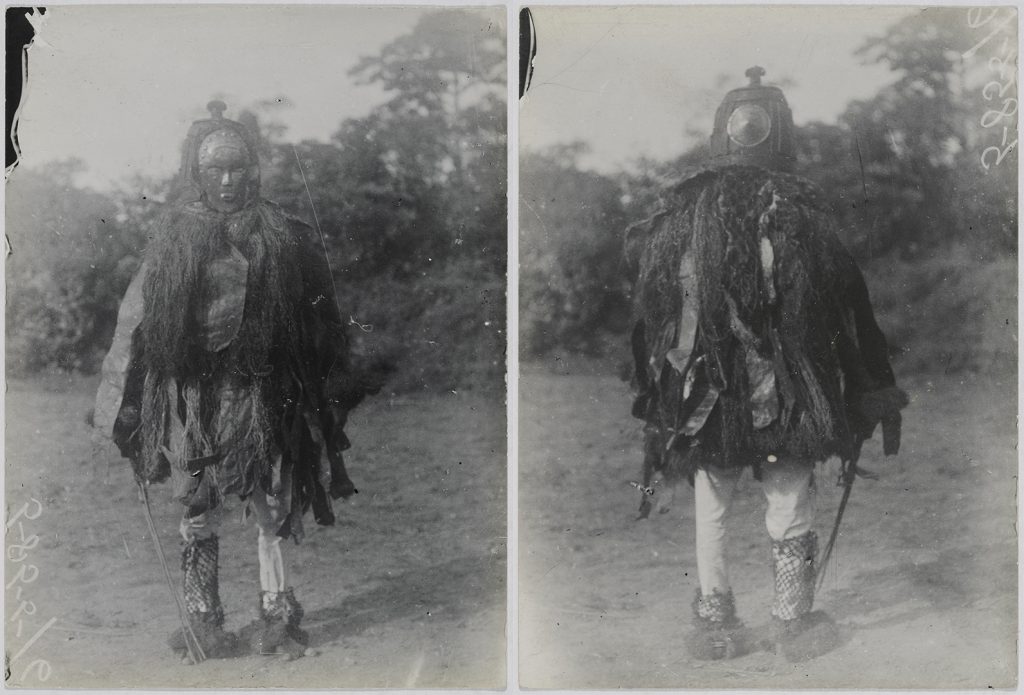

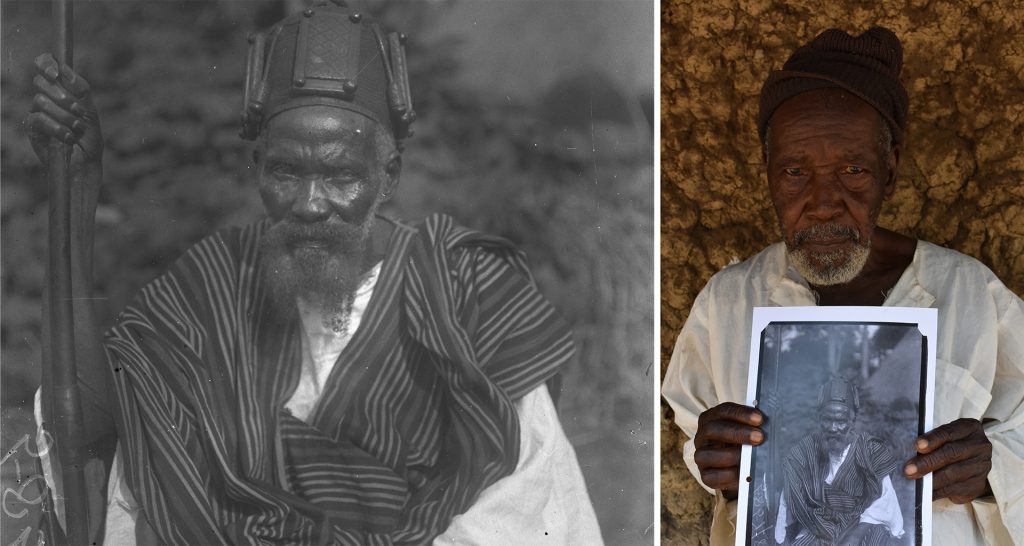

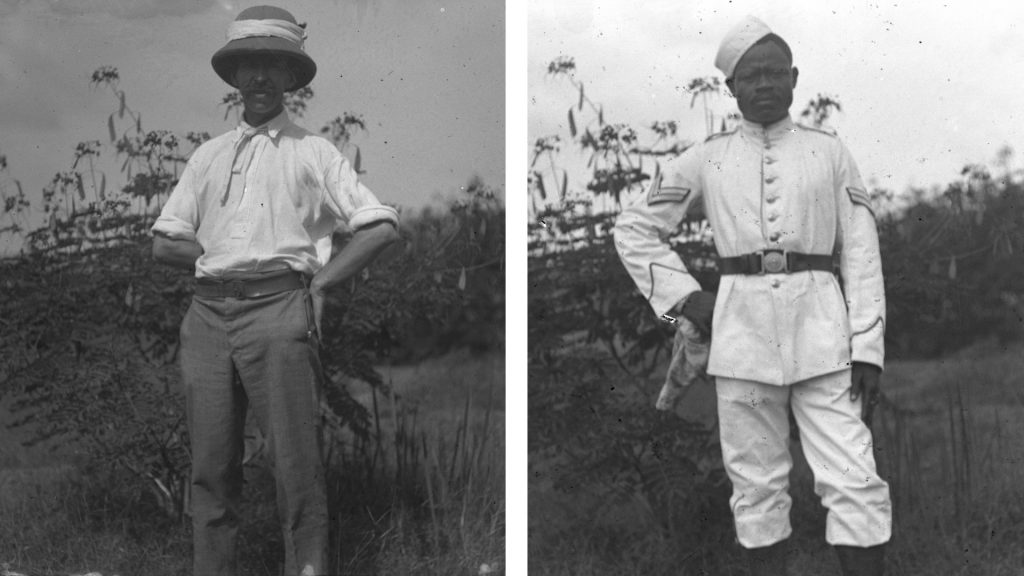

John was, of course, just one of many assistants that accompanied Northcote Thomas on his travels in Nigeria and Sierra Leone. John represents all those who straddled, perhaps uneasily, the worlds of the British colonialists and the indigenous populations. They were rarely the main subject of Thomas’s photographs, but they appear occasionally in the periphery. There is an interesting pair of photographs, one presumably taken by Thomas of a uniformed man, wearing the stripes of a corporal. We believe this is Corporal Nimahan, a corporal in the Police Force and one of Thomas’s main interpreters in 1909-10. Nimahan and John Osagbo would have travelled together, and we imagine the older man cautioning John not to allow himself to be enthralled by the world of the colonialists (reminding him he is merely a ‘servant’ after all). The other photograph, taken in exactly the same location, beside the same bush, is of Thomas himself, most likely taken by Nimahan.

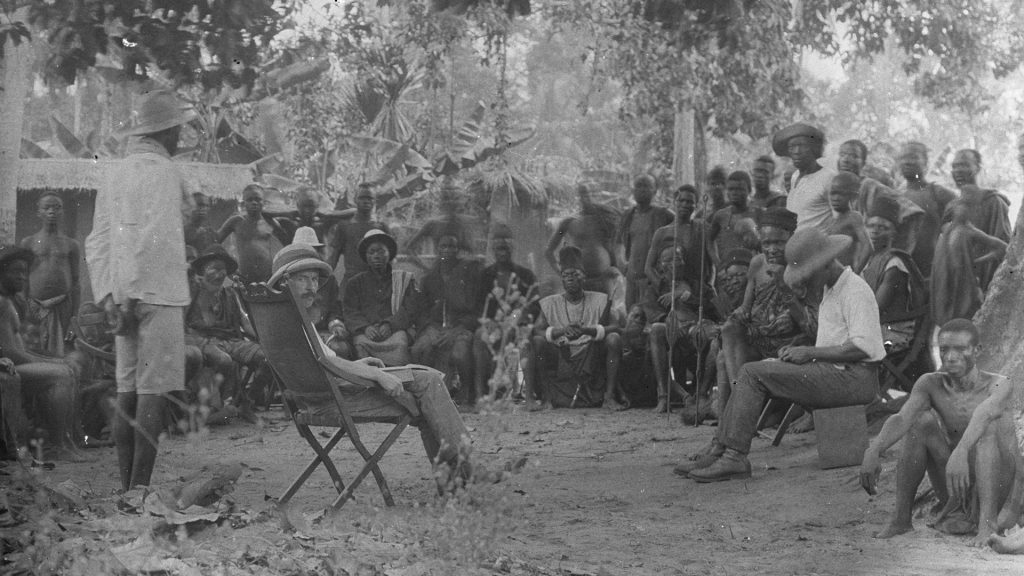

Interpreters and assistants can be seen in other photographs made during the anthropological surveys, including in a photograph – again presumably taken by one of Thomas’s assistants – of a meeting of chiefs to discuss a land dispute in Neni, present-day Anambra State, in 1911. John tells the story of these people ambiguously caught between worlds. They are part of the African world that Thomas was researching, but also caught up – at least for a while – in the world of the researcher and the colonialists. Dressed like the white anthropologist, jotting down notes, operating the camera and the phonograph, how were they perceived by the local people? We can read much into the interchange of gazes in the photograph taken in Neni. This being ‘between worlds’ has become an increasingly familiar experience. Many of the descendants of those photographed may have migrated to or been born in Europe or North America, and speak English as a first language, yet still retaining a profound connection to Africa. (See, for example, Obianuju Helen Okoye’s article on Ancestral Reconnections.)

See also Peripheral presences: N. W. Thomas’s field assistants.

Bringing the archive to life through storytelling

Unspoken Stories was a collaboration between the [Re:]Entanglements project and the storytellers who gave voice to these five characters from the archive. They were led by the Sierra Leonean storyteller, Usifu Jalloh, also known as The Cowfoot Prince. Jalloh was born in Kamakwie in the north of Sierra Leone, attended St Edwards Secondary School in Freetown, and began his professional storytelling career as a member of the famous Tabule Theatre group. In the remainder of this article, he discusses how West African storytelling traditions can bring the anthropological archives of Northcote Thomas to life.

As a professional storyteller, I have learnt that stories are the palm oil with which wisdom is swallowed. The work that Northcote Thomas did in many ways reflects the traditions of oral storytelling. Most African kingdoms and communities have designated families entrusted with and dedicated to learning, archiving and telling the stories of the past. These people are called Djali among the Malinke people of West Africa.

Through the voices of these highly respected people we are able to access the lives of ancestors past. Their stories are sometimes yardsticks embedded with moral and ethical codes that guide the smooth running of the community.

Storytelling is used effectively today to connect the younger generation to their ancestral identity. One way this is done is by understanding names given to certain children or objects. Names are used in storytelling to maintain genetic continuity. My name is Jalloh. It identifies me to be a Fulla and that I am from a merchant clan. The same is true for names belonging to blacksmiths, hunters and farmers. This is one important aspect of information for a storyteller in order to influence and maintain traditions of old.

Through the names recorded by Northcote Thomas we are transported back to the narratives of families a hundred years ago and more. We have been able to reawaken the lives of ancestors into a contemporary paradigm through the objects, sounds, photographs and names provided. Much like the ancient Djali did and still do.

To bring these characters to life we had to search within our own cultural experiences. Each chosen character resonated deeply within all the tellers for this project. All the storytellers had to draw from their practical experiences to give the narratives of these characters a real time relevance.

For example, I related to Ngene as I am also a part of the rites of passage fraternity in my community. We have the Matoma masquerade, which is revered and serves as a protector for the farms. There is Bondo, which Yainkain must have been part of during her rites of passage from girl to womanhood. My grandmother was the one who initiated many girls. I grew up with many aunties like Yainkain, beating drums and singing all night during initiation ceremonies.

In addition to this is the dual Afro-colonial narrative, which John embodies. I went to a school with a strict European paradigm, and we were all taught in a manner that encouraged us to leave behind our identity as native Africans to embrace the new ‘civilised’ Western ways. We wore suits and ties to school, and learnt and spoke English, French and Latin with pride – usually in spite of our native tongue. We saw John as a young man in this dual thought process, which many young Africans still experience today.

The curiosity of children is as present today as it was back a hundred years ago. I can still remember the fascination of standing in front of a camera for a photoshoot with my family. It was usually a special event where we will dress up with our Sunday best, as we called it. We would wait with excitement for a few days for the photos to be printed and then show off to all friends and relatives who visited our home.

The fascination of seeing a white person is still yet another attraction. Rumours and hearsays of the whiteman coming to catch the evil spirit, Kassila, at the river were rife because white people seemed not to be afraid of swimming far into the river where the evil Kassila resides. These were useful reflections while the storytellers were developing the story for the children. There was also ample information given in the records of Northcote Thomas that formed a springboard for us to leap from.