There is a wealth of cultural and historical knowledge locked away in the sound recordings that Northcote Thomas made during his anthropological surveys of Nigeria and Sierra Leone in the early twentieth century. Recorded on wax cylinders using a phonograph and without the benefit of a microphone, these sound archives are, however, some of the most challenging materials to work with. The audio signal is often weak, and the levels of noise very high.

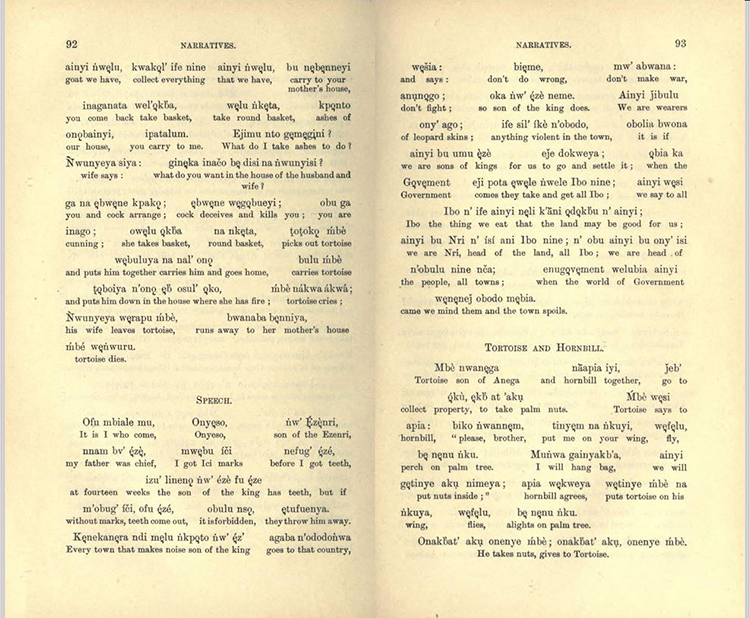

Working with Yvonne Mbanefo of the Igbo Studies Initiative and thanks to a small grant from the British Library, which cares for Thomas’s wax cylinder recordings today, we have begun to transcribe, translate and re-record some of the the audio tracks. We have also been revisiting some of the transcriptions and translations that Thomas published in his Anthropological Reports. The original transcriptions and translations have proven to be invaluable in re-engaging with the recordings, but they can also be quite inaccurate.

During his 1910-11 tour of what was then Awka District (corresponding more or less to present-day Anambra State, Nigeria), Thomas spent a considerable amount of time at Agukwu Nri. Nri was an extremely important town in Igboland, the seat of the ‘highest ritual political title’, the Eze Nri. The reigning Eze Nri at the time of Thomas’s visits was Obalike. During the [Re:]Entanglements project, we have had the privilege of presenting Eze Nri Obalike’s grandson with a hitherto unknown photographic portrait of his grandfather made by Thomas.

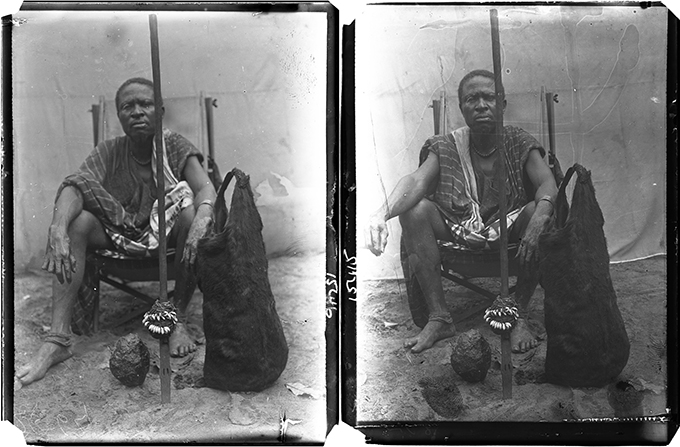

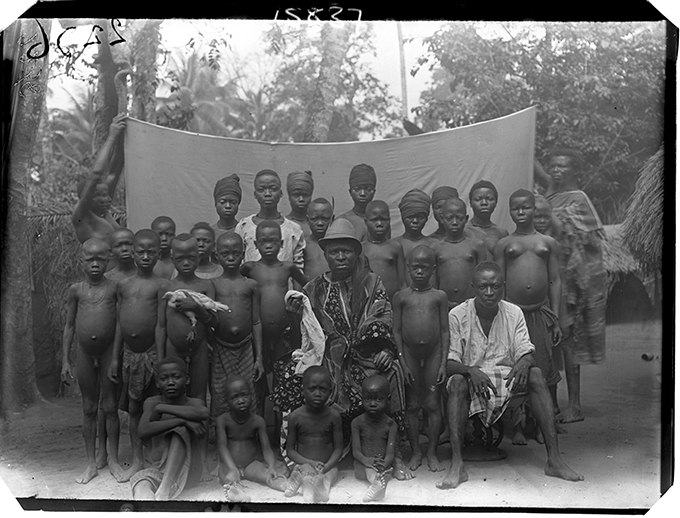

Another important figure in Nri at the time of Thomas’s anthropological survey was Chief Onyeso. Onyeso was the son of the previous Eze Nri, Enweleana, and had served as regent during the interregnum between the reigns of Enweleana and Obalike. Whereas the Eze Nri was a spiritual leader, it appears that Onyeso remained a powerful ‘secular’ leader. As well as photographing him and his family, Thomas recorded a speech by Onyeso. In this case, the original recording seems not to have survived, but there is a transcription and translation of the speech in Part III of Thomas’s Anthropological Report on the Ibo-speaking Peoples of Nigeria; a volume devoted to ‘Proverbs, Narratives, Vocabularies and Grammar’.

Below is a rendering of the text of Onyeso’s speech in standard Central Igbo together with a revised English translation, both provided by Yvonne Mbanefo.

Ọkwa mụ na abịa, Onyeso, nwa Ezenri,

It is I who come, Onyeso, son of Ezenri

Nna m bụ Eze. Egburu m ichi n’epughị eze

My Father was the King, I got Ichi marks before I got teeth

N’izu iri na anọ, nwa eze na-enwe eze,

At fourteen weeks the son of the King has teeth,

mana ọ bụrụ na ọ nweghị ichi,

But it happened that he didn’t have ichi marks.

Eze pụta, ma ichi adịghịị, anaghị ekwe, aga etufu ya.

but if the teeth come out without the marks, it is forbidden, they throw him away.

Obodo ọbụla mere mkpọtụ.

All the towns made noise.

Mana nwa eze, gaa n’obodo ahụ,

But the son of the king, went to the town.

Wee sị, emena ihe ọjọọ, e buna agha , anụna ọgụ

and said, ‘Don’t do bad things, don’t start wars, don’t fight’.

Ọ ihe a ka nwa Eze na-eme.

That is what the son of the King does.

Anyị na-eyi akpụkpọ agụ

We are the wearers of leopard skins

Ife siri ike n’obodo.

Things are hard in the town.

Anyị bụ ụmụ eze. Anyị ga-eje dozie ya.

We are the children of the King.

Ọbịa ka Gọọmentị jị bịa kpọlụ ndi Igbo niile.

The Government was visiting and took all the Igbo people.

Anyị wee sị ndị Igbo niile na ife anyị na-eme, ka ala dịrị anyị mma.

We are then saying that all Igbo that what we do, to make the land good.

Anyị bụ Nri, Isi ala Igbo niile.

We are Nri people, head of the entire Igbo land.

Anyị bụ isi ọbọdọ niile, mmadụ niile .

We are the head of all the towns, and all the people.

Oge ụwa Gọọmentị bịara , anyị wee lee, obodo mebie.

When the Government came, we looked, and the town got spoiled.

Onyeso’s speech is remarkable for many reasons. In this text, we can hear the voice of one of Thomas’s prominent interlocutors – a known, named individual, who Thomas also photographed. It is the voice of a confident, defiant member of an aristocracy, highly critical of the British colonial government, which has usurped the authority of traditional rulers, and undermined the status of the royal town of Nri. Onyeso asserts the primacy of the Nri people as the ‘head of the entire Igbo land’, a ritual and political status discussed at length by the Nigerian anthropologist M. Angulu Onwuejeogwu in his book An Igbo Civilization: Nri Kingdom and Hegemony (1981).

Onyeso also provides first hand details about some of rituals around his office and the political functions of the nwa eze, the son of the king. He refers, for example, to the traditional practice of infanticide. A newborn child is not supposed to have teeth, and if it does this was traditionally considered an abomination, resulting in the child being left to die in the forest. Similarly, a baby who cut his upper teeth first was also considered an abomination. Onyeso states that the sons of kings cut their teeth early, but that it is important for them first to have the ichi facial scarification marks made – if they haven’t received the ichi marks, the child, he says, will be thrown away. Onyeso proudly states that he received the ichi marks as a baby before his teeth came through.

Onyeso also explains that the nwa eze acts as a peace-maker, travelling to towns, quelling disturbances and quarrels, advising towns under the Nri hegemony to keep the peace. This was an important role for Onyeso since the Eze Nri himself was traditionally prohibited from travelling outside of Nri after his coronation. As Onwuejeogwu argues, the Eze Nri ‘ruled but was never seen by the people of his hegemony’. The sacred status of the Eze Nri was undermined by the British colonial authorities; part of the destruction of the traditional order to which Onyeso alludes in his speech.

And what of the Government Anthropologist? Thomas’s position seems to have been ambiguous. On the one hand, he was surely associated with the forces of colonialism that were destroying the Nri hegemony. On the other hand, however, he contradicted colonial officials and sent despatches to the Colonial Office arguing that the ritual authority of the Eze Nri should be respected. He also documented the voices and words of people like Onyeso, representing the experiences of colonisation from the perspective of the colonised in his official Reports. One wonders how many people, even to this day, have actually read Onyeso’s speech or recognized how subversive an act it was of Thomas to include such anti-colonial sentiments in publications funded by the colonial government and distributed to colonial administrators.

Many thanks to Yvonne Mbanefo, Oba Kosi Nwoba, Janet Topp Fargion and British Library Sounds for supporting our research on Northcote Thomas’s sound recordings.

Comment from Ifeanyi Edemba via Nigerian Nostalgia Project Facebook page:

“Anyị wee sị ndị Igbo niile na ife anyị na-eme, ka ala dịrị anyị mma.

We are then saying that all Igbo that what we do, to make the land good.”

I think there’s a misinterpretation here. The first “na” could have been “nee”. The entire sentence will then be:

“We tell all the Igbo people, look at what we do, that the land be good for us”.