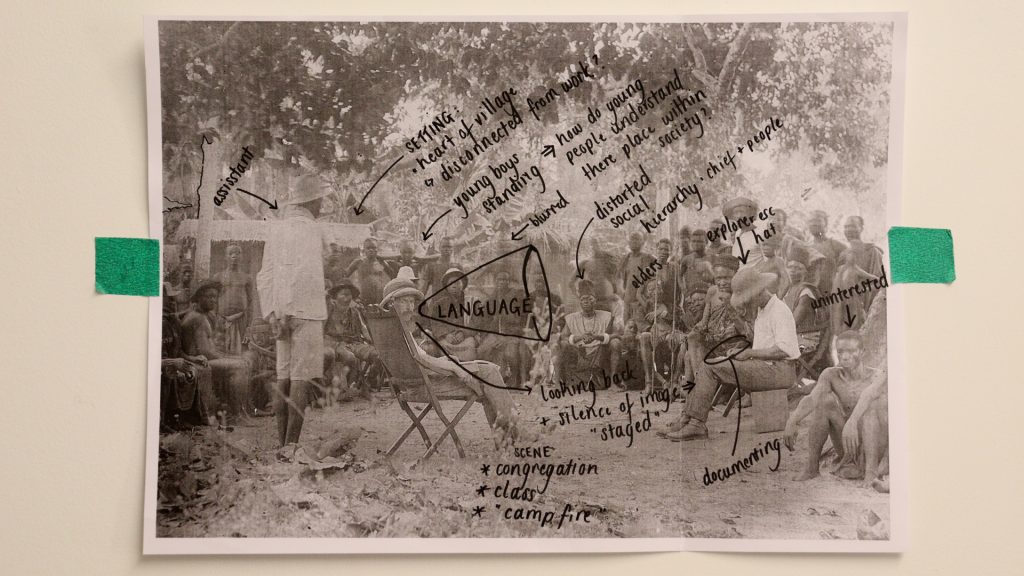

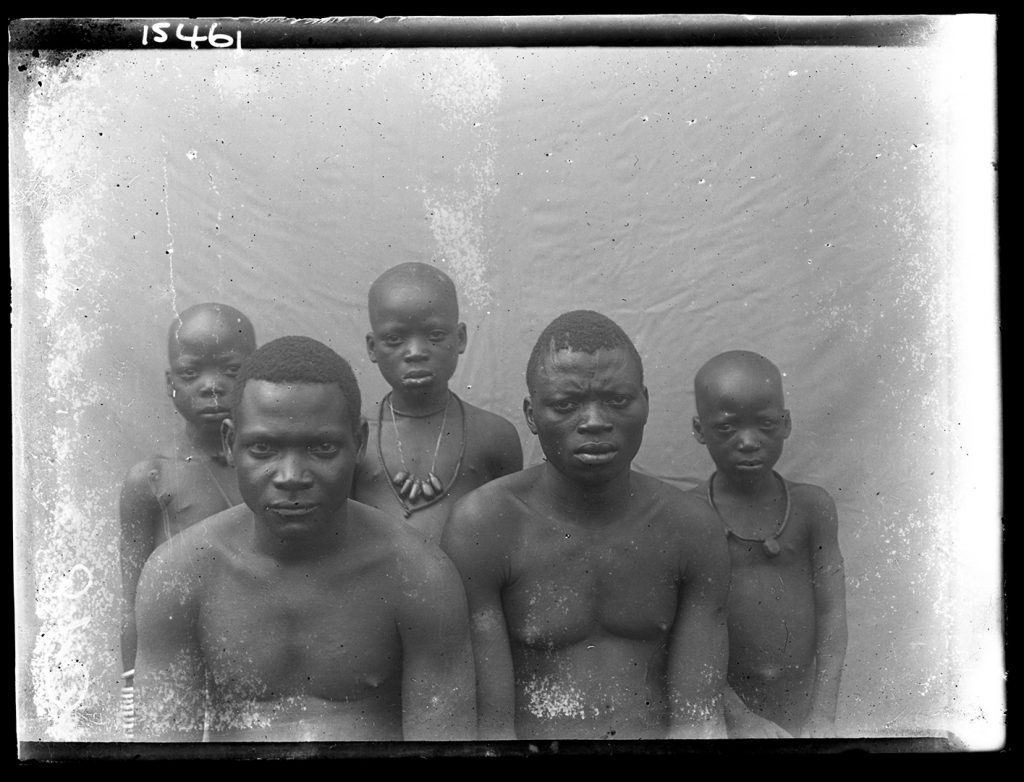

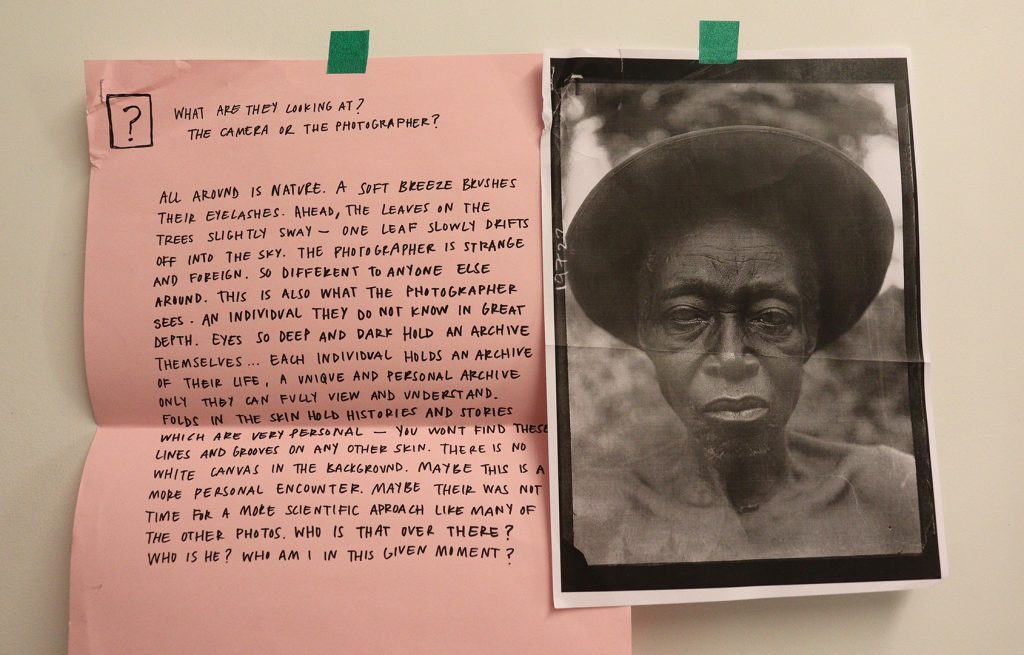

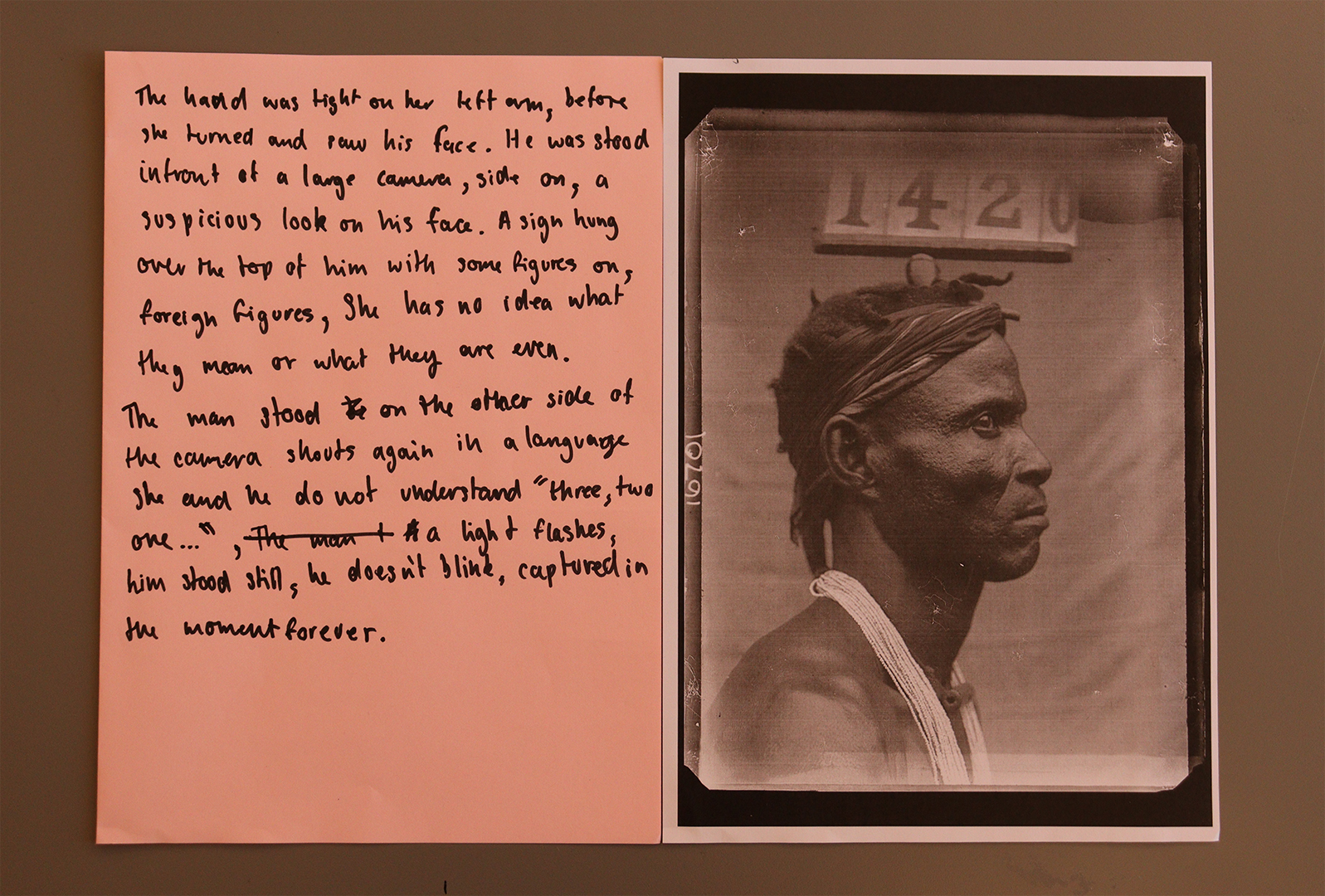

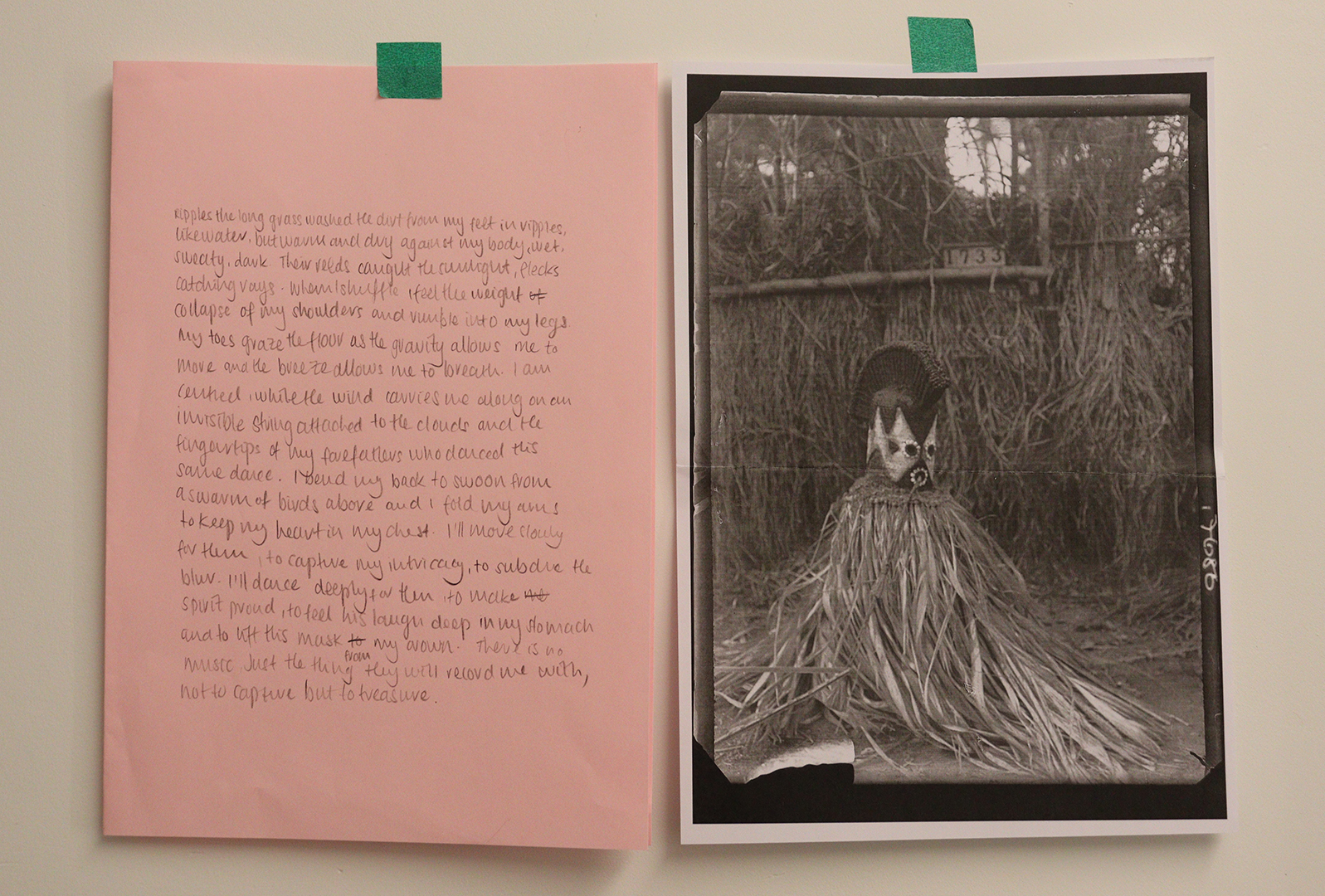

During his anthropological survey of the Edo-speaking people of Nigeria in 1909-10, Northcote Thomas spent several months working in Benin City itself. His photographs of the City’s prominent chiefs, its architecture, shrines and markets provide an important record of the capital of the Benin Empire just 12 years after its fall at the hands of the British Punitive Expedition. Although accounts of the sacking of Benin City in 1897 suggest that little was left of Benin’s centuries-old civilization, it is clear from Thomas’s photographs that much escaped destruction and not everything was looted.

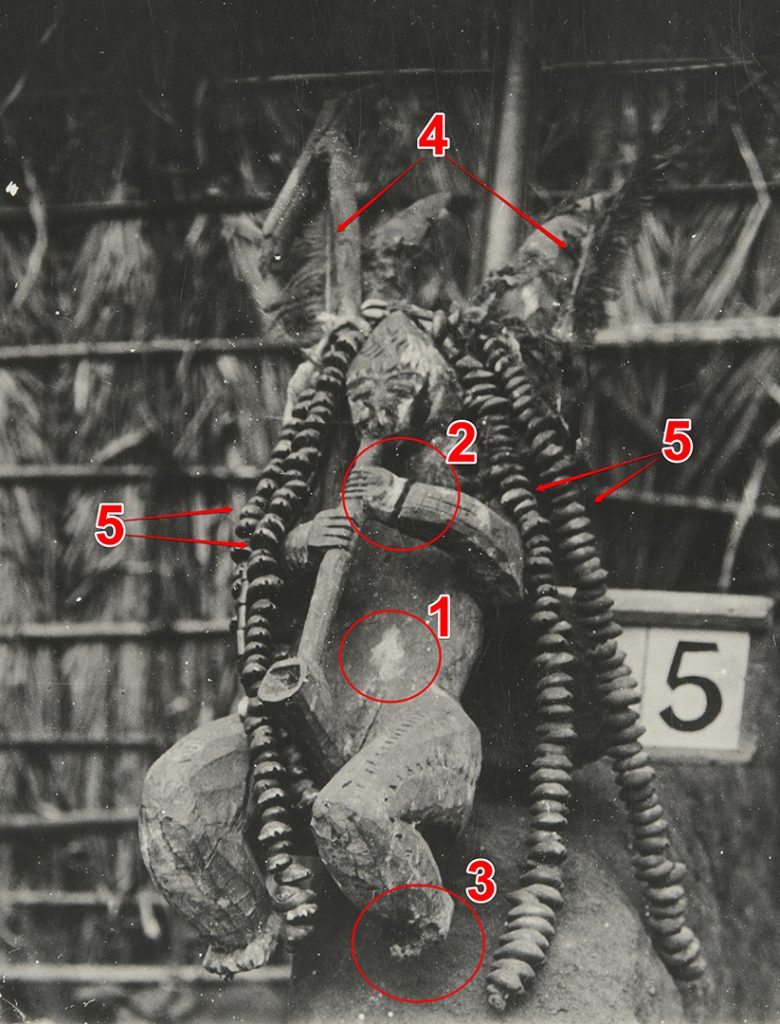

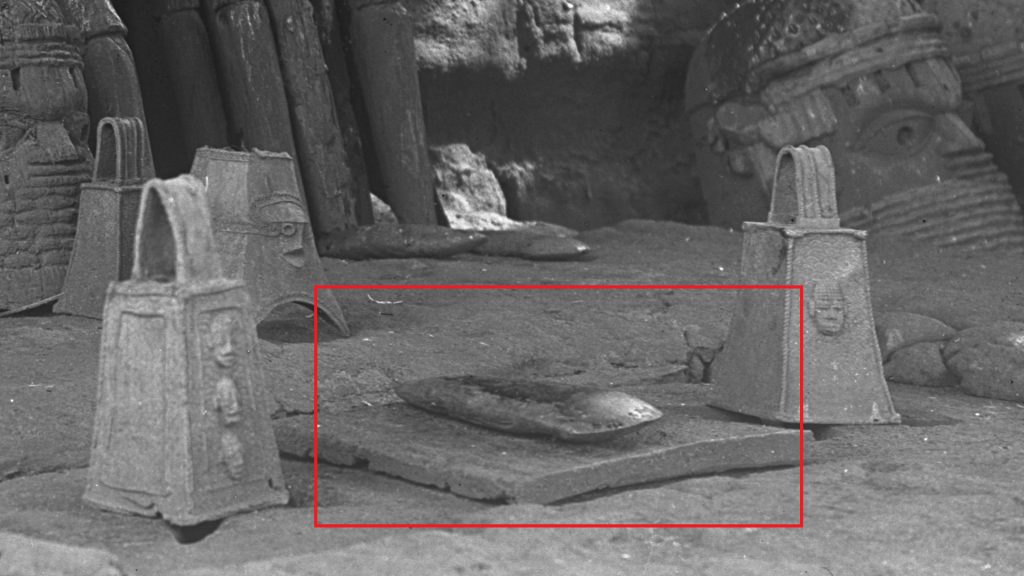

Thomas documented a number of Benin shrines in considerable detail. His photographs of the ancestral altar at Chief Ezomo‘s palace, for example, shows many of the classic Benin shrine objects such as rattle staffs (ukhurhẹ), memorial heads (uhunmwun) and altar bells (eroro). Of these ritual objects, Thomas seems to have been particularly intrigued by the presence of polished stone axes or celts in these assemblages.

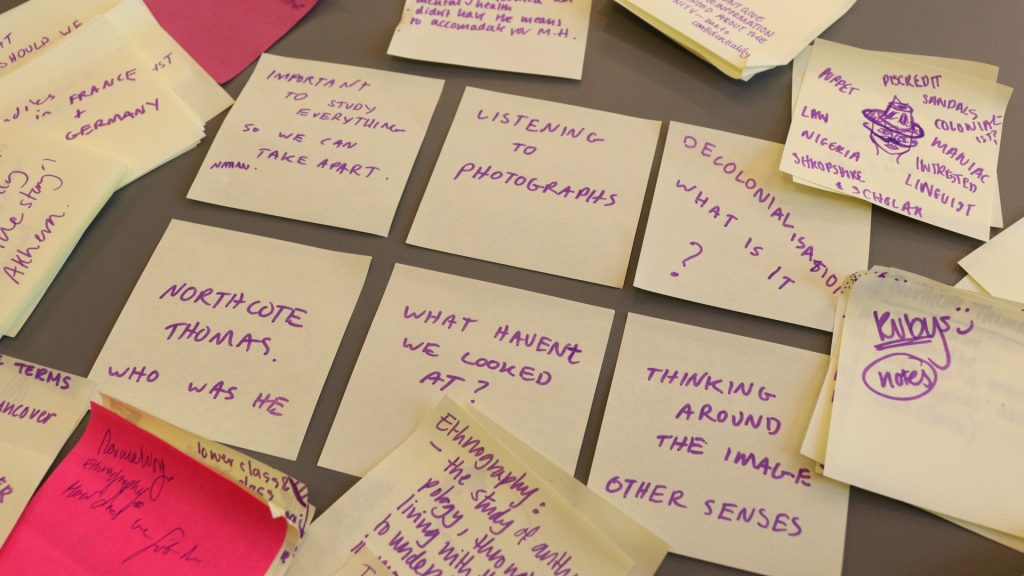

Thomas’s anthropological reports and other publications contain no information about these stone axes. Indeed, it is important to note that the vast majority of Thomas’s fieldwork findings remained unpublished. In a letter written in 1923 to his friend and colleague Bernhard Struck, Curator of the Museum für Völkerkunde in Dresden, he notes that he published only 10 per cent of his material from his Edo tour – that deemed to be of relevance to members of the colonial service. Among the fragments of unpublished fieldnotes and manuscripts that survive, however, there are a few pages in which he discusses the celts.

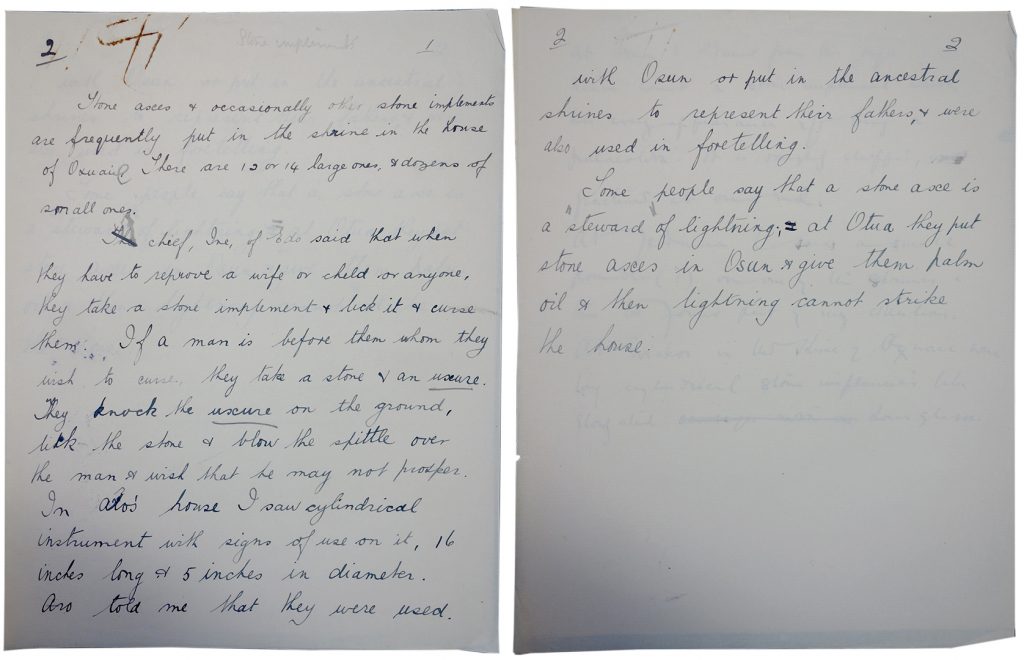

Thomas writes that ‘Aro [i.e. Chief Ero] told me that they were used with Osun [a deity] or put in the ancestral shrines to represent their fathers, and were also used in foretelling’. They could also be used as objects to swear by or curse: ‘Chief Ine of Edo said that when they have to reprove a wife or child or anyone, they take a stone implement and lick it and curse them. If a man is before them whom they wish to curse, they take a stone and an uxure [ukhurhẹ]. They knock the uxure on the ground, lick the stone and blow the spittle over the man and wish that he may not prosper’.

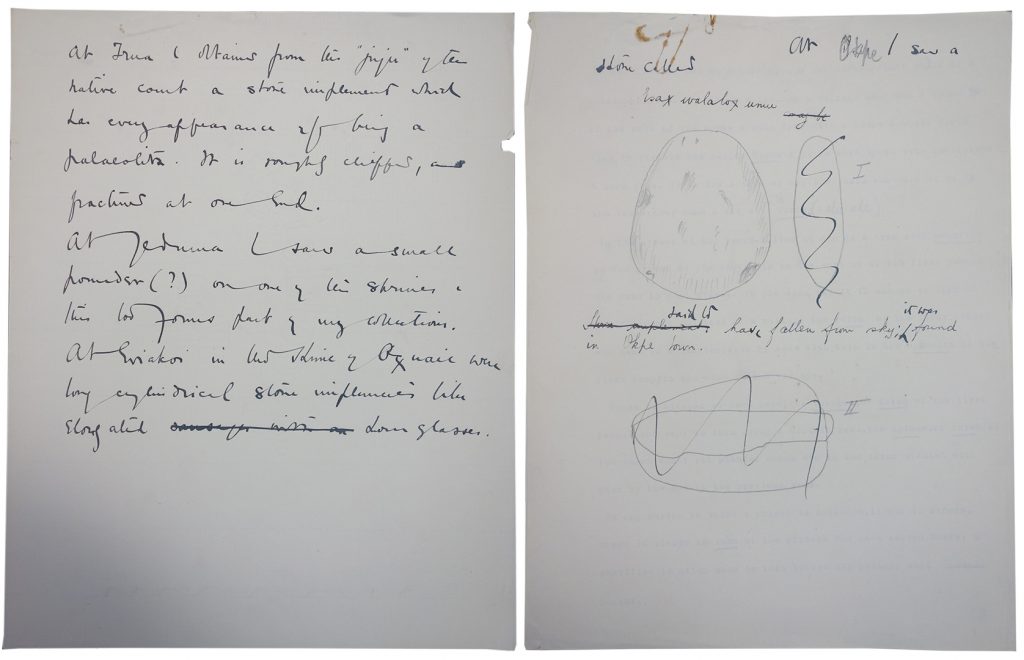

It was not only in Benin City that Thomas encountered these stone implements. He also records examples in Irrua, Okpe, Otua and other locations in what is today Edo State. At Okpe he was shown a stone called ‘esax evalalox umu‘ [?] that was said to have fallen from the sky. Elsewhere he was told that ‘a stone axe is a “steward” of lightning’, and in Otua he explains that they are placed in the Osun shrine, and if they are given palm oil (as a sacrifice), then lightning will not strike the house.

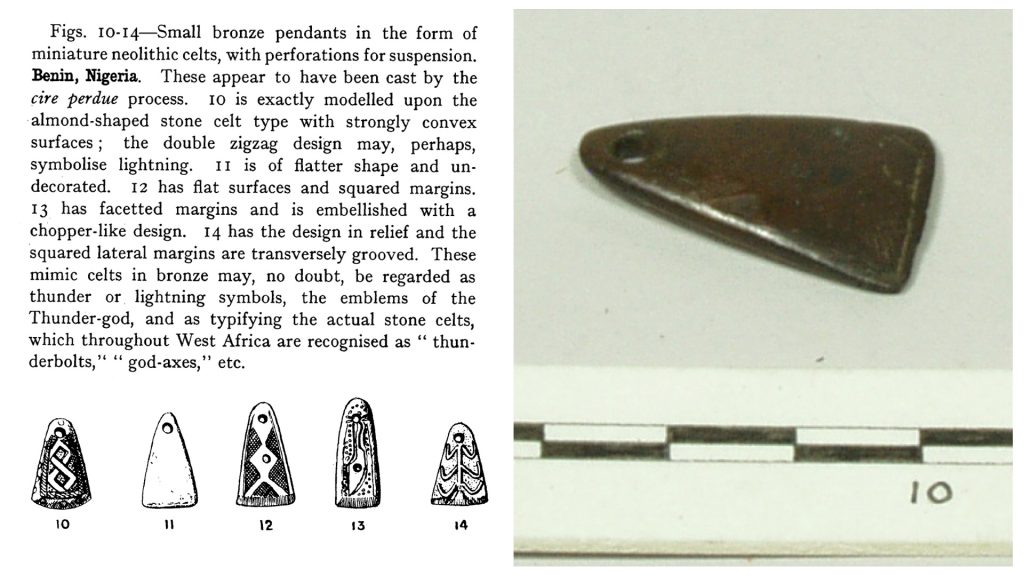

The association between these axe heads and lightning is widespread, not only throughout West Africa, but also in Europe and elsewhere, where they are regarded as ‘thunderbolts’ or ‘thunderstones‘ – weapons wielded by gods of thunder, hurled to earth, and not of human manufacture. In 1903, Henry Balfour, Curator of the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford, had written about such ‘”Thunderbolt” Celts from Benin’ in the anthropological journal Man, which was then edited by Thomas. In a later article in Folklore, in which he surveyed the phenomenon of thunderbolts throughout the world, Balfour also discussed a number of small bronze pendants in the Pitt Rivers Museum collection made in the form of miniature stone axes, which had also been acquired in Benin City

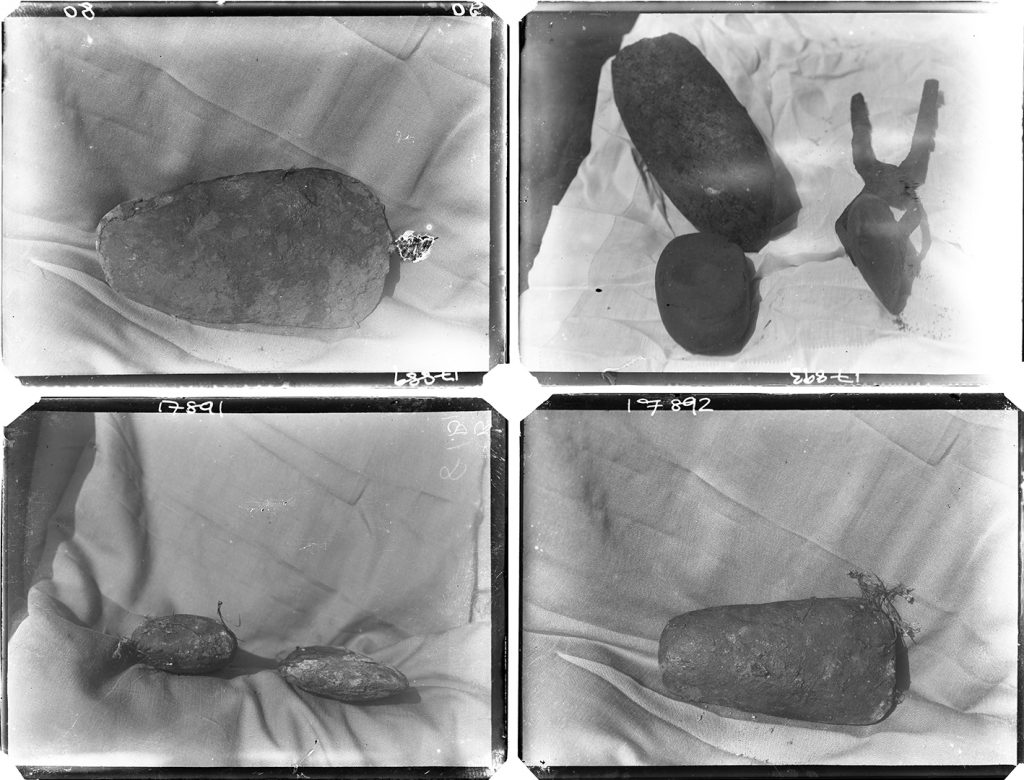

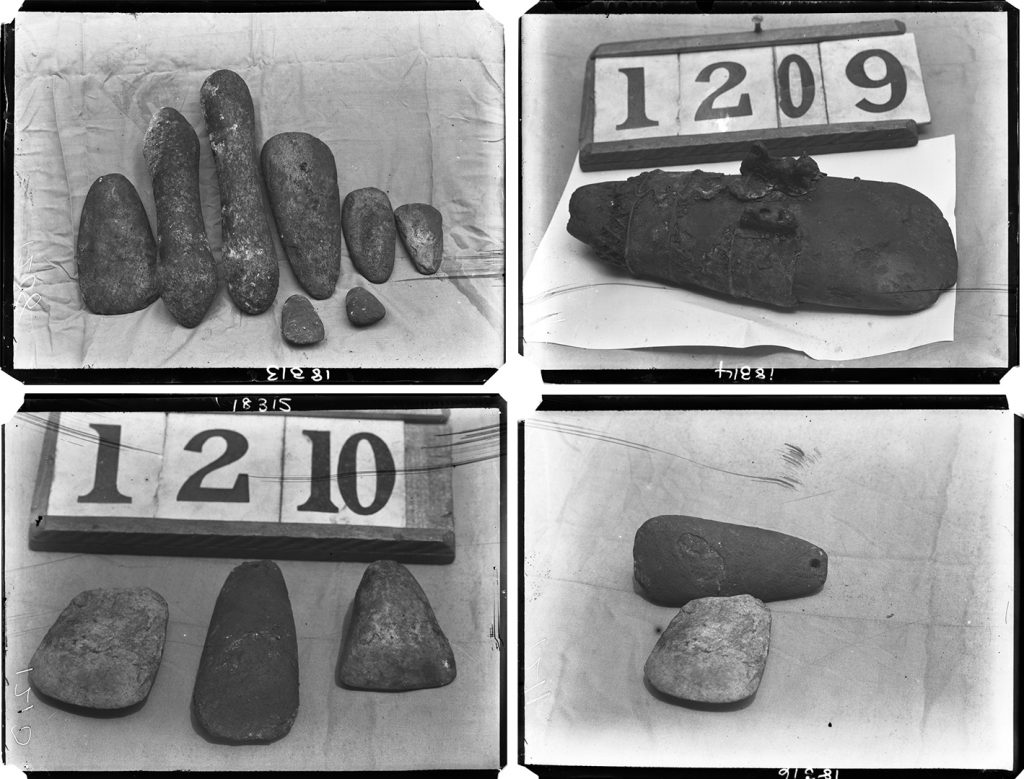

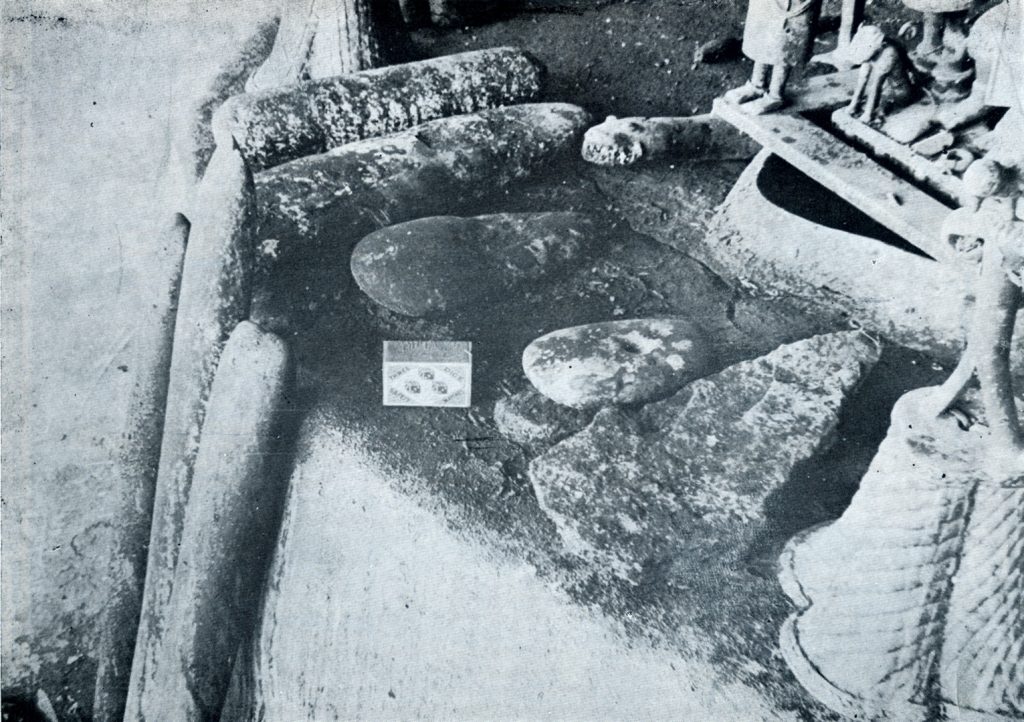

In addition to the examples he photographed at Chief Ezomo’s palace, Thomas also photographed an assemblage of stone axes from an ancestral shrine at Chief Ogiame’s palace in Benin City, and another set at a shrine dedicated to the deity Oxwahe at Eviakoi, in the north-west outskirts of Benin City. Thomas also appears to have collected a number of examples, including one evidently dug up during forestry operations, although we have been unable to trace any of them during our research at the University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology stores.

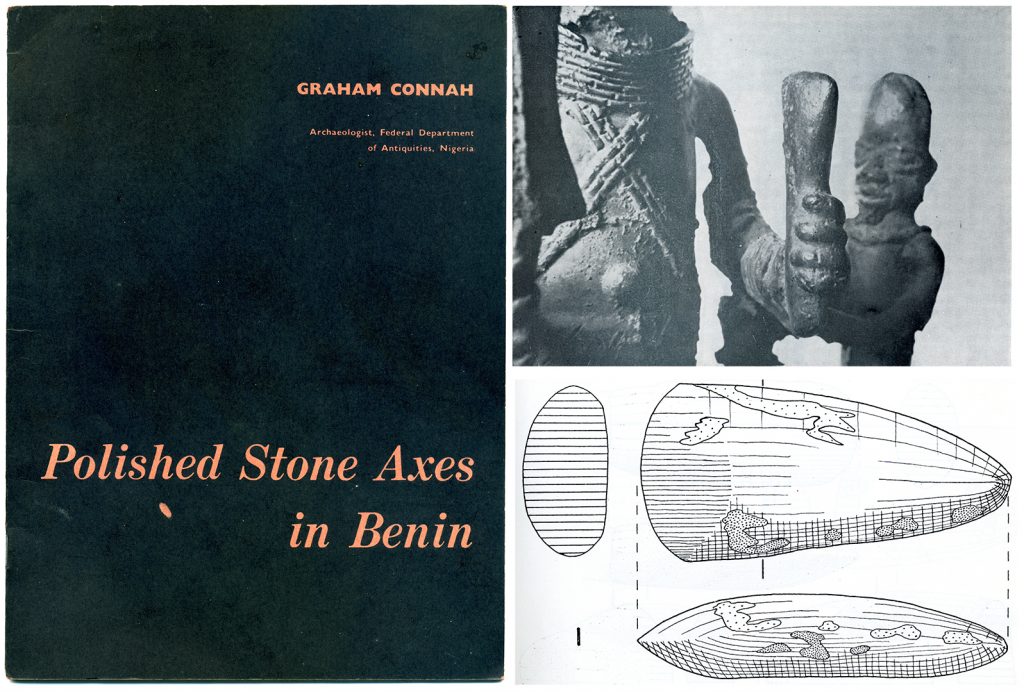

It was not until Graham Connah‘s Polished Stone Axes in Benin, published in Nigeria in 1964, that a more substantial study of these stones became available. A British archaeologist, Connah had been appointed by the Federal Department of Antiquities to conduct a programme of archaeological excavation in Benin City in 1961. Connah was interested in these prehistoric stone axes since they represented the earliest evidence of ‘human industry’ in the region. During his research, Connah was able to consult authorities such as the well-known historian and curator of the Benin Museum, Chief Jacob Egharevba, as well as the Oba of Benin, Akenzua II, himself.

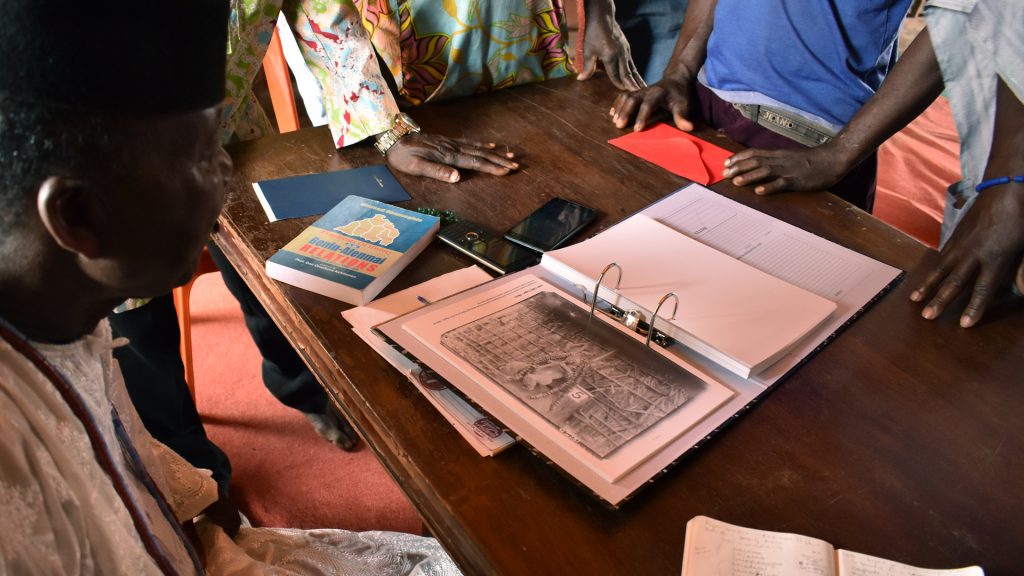

Connah provided a review of the existing, though scant, literature on the celts and drew attention to the depiction of such axes in some of the famous Benin bronze artworks. With Egharevba, he also acquired over 20 examples for the Benin Museum, the close examination of which formed the focus of his publication. It is evident that Connah had no knowledge of Northcote Thomas’s unpublished photographs and notes, which would have otherwise made an important contribution to his study.

In the present context, perhaps the most interesting section of Connah’s publication is that on ‘Bini beliefs about stone axes’. Connah notes that the Bini call the axes ughavan, a contraction of ughamwan (axe) prefixed to avan (thunder), and meaning ‘thunder-axe’ or ‘thunderbolt’. In the early 1960s they were evidently not uncommonly found on household shrines throughout Benin City, and Connah states that they could be seen on Oba Akenzua II’s shrines to his predecessors, Eweka II, Overamwen and Adolo. In historical bronzes, obas are sometimes depicted holding an ughavan in their left hand. Here, its function is ‘to increase the potency of a cursing or blessing’.

Connah further notes that there was no realisation in Benin that these prehistoric stone tools had a functional origin. ‘To the Bini’, he writes, ‘they are “thunderbolts”, and “thunderbolts” they remain. Any suggestion that they could be stone tools made at a time before the availability of iron in West Africa is met by polite misbelief’. He also doubts that they have been made in more recent centuries for ‘cult purposes’, having recorded stories about how they were found during farming or embedded in trees that have been struck by lightning.

In her recent book, Iyare! Splendor and Tension in Benin’s Palace Theatre, Kathy Curnow provides a succinct summary of these fascinating objects:

Prehistoric stone axe heads antedate metal tools. Easily damaged, they were tossed away and replaced, and readily turn up today when land is farmed. In Benin, as in many other parts of the world, they are not always recognized as man-made objects. Instead, they are considered thunderstones (ughavan), the product of lightning strikes. The Edo believe Ogiuwu, the god of death, hurls them to the ground as manifestations of his power and anger. The Oba likewise has the right to kill, and gripped thunderstones or celts to magnify his curses. Still kept on altars, they call the ancestors into service as witnesses and supporters.

References

- Balfour, H. 1903. ‘”Thunderbolt” Celts from Benin’, Man, vol.3, pp.182-3.

- Balfour, H. 1929. ‘Concerning Thunderbolts’, Folklore, vol.40, pp.37-49, 168-173.

- Connah, G. 1964. Polished Stone Axes in Benin. Nigerian National Press.

- Curnow, K. 2016. Iyare! Splendor and Tension in Benin’s Palace Theatre. University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology.

- Plankensteiner, B. (ed.) 2007. Benin Kings and Rituals: Court Arts from Nigeria. Snoeck Publishers, Ghent.

All Northcote Thomas photographs reproduced here have been scanned from the glass plate negatives in the collection of the Royal Anthropological Institute, and are reproduced courtesy of the Institute.