In her latest blog post from UCL’s Conservation Lab, Carmen Vida discusses how Northcote Thomas’s historical field photographs inform the work of reassembling ‘composite’ objects from the collection and help conservators’ make decisions about appropriate conservation treatments.

It often comes as a bit of a surprise to people when they first get to know about museum conservation to learn that conservators do not necessarily always do everything that can be done to an object, or try to make it complete, new, or ‘like it was’. Out of many possibilities, conservators decide on what is an appropriate treatment for each object in dialogue with experts, curators and other stakeholders. As a conservator, I am very aware that every conservation intervention is a new event in the life of an object, an event that can be ‘life-changing’ – though, hopefully, a change for the better by extending the object’s life and making it more meaningful to others. It is the conservator’s job to ensure that the conservation intervention always fits with and helps reveal what the ‘life’ of the object was and is, and that it never obscures its significance, values and stories, but rather helps to reveal them.

For conservators, damage is not always bad. It can, rather, be an interesting thing: it can, for example, tell us about the way an object was used, help us to understand its ‘biography’, inform us about the conditions in which it has be stored, and so forth. For this reason, conservation always starts with research and investigation. We seek to get to know an object as closely as possible through documentation, through comparison with similar or related objects, and through the signs left on the object by its previous history. This helps us to design conservation treatments that fit with the object’s past history as well as its present and future use. In a way, conservation is a bit of a time machine, moving between the object’s past, present and future!

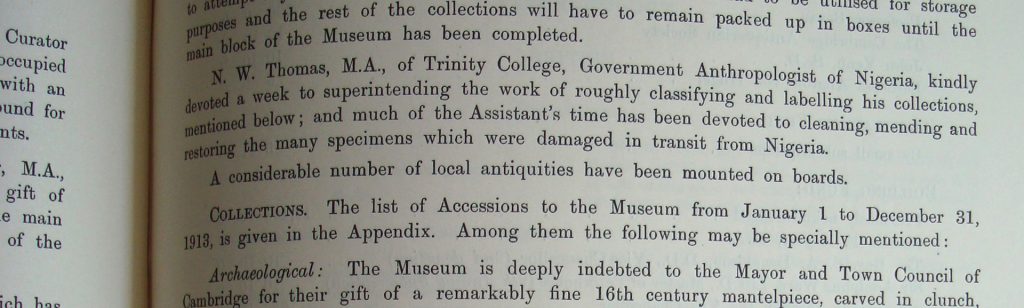

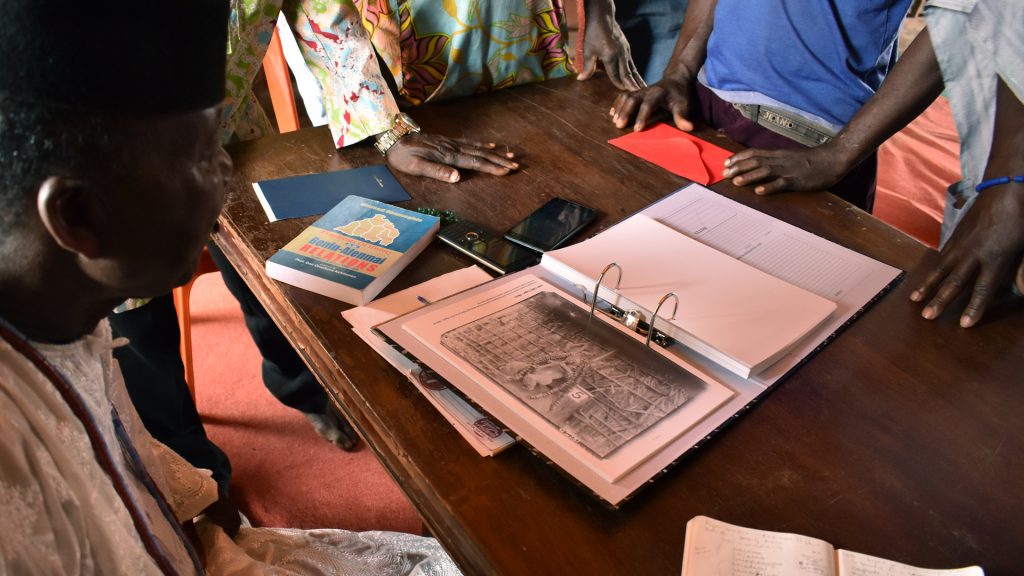

As discussed in a previous post, Giving Objects a Voice, many objects appear to be ‘mute’. That is, they have no accompanying information, and conservators must rely entirely on what they can discover from their analysis of the object itself. But working with the collections assembled by Northcote Thomas is providing me with a unique opportunity because the archive itself is so rich and varied: not only objects, but written records, sound recordings and, very importantly for the conservator, historic photographs. These different elements in the archive can sometimes be brought together to shed light on each other. So just as the historic photographs of people have been affording their descendants in West Africa the possibility of reconnecting with their ancestors (see for instance the blog Ancestral Reconnections), the historic photographs of the objects are affording conservators the possibility of reconnecting with the earlier life of some of the objects we are treating. This information is vital to guide our conservation treatment choices because it allows us to compare two different moments in the life of the object, and it helps us decide what the treatment should achieve and how. It ultimately helps us make ethical treatment decisions.

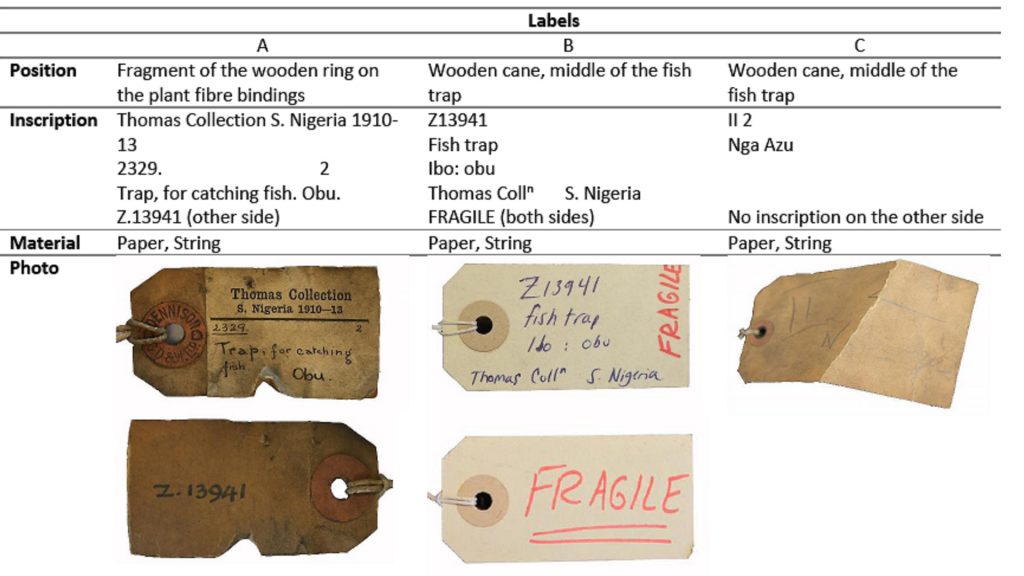

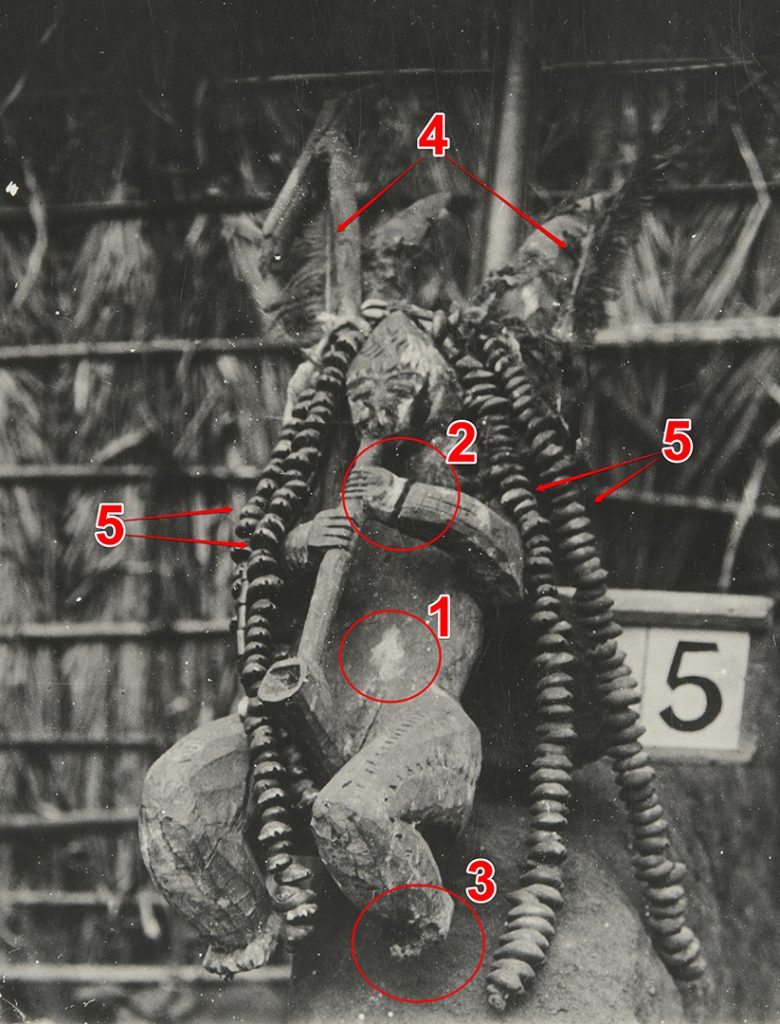

Some of the objects we have been working with in the UCL Conservation Lab illustrate this well. I have recently been revisiting the treatment of a figure that Thomas collected in Fugar in present-day Edo State, Nigeria, in 1909, which was conserved by one of our students last summer. In Thomas’s catalogue, the figure is labelled with the single word ‘akosi’, with no further information. The object is a ‘composite’ insofar as it consists of several elements and materials: (1) a carved wooden figurine with a feather, (2) a red glass bead ‘necklace’ or ‘bracelet’, and (3) a ‘headdress’ consisting of strings of cowrie shells threaded though cane and plant material. At the University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, these three elements have been accessioned and stored separately. Bringing together the [Re:]Entanglements project’s archival research, collections-based research and fieldwork, it has, however, been possible to re-associate the elements that make up this assemblage with reference to a photograph that Thomas made of the figure at the time of collection. This, we assume, shows the assemblage as Thomas initially encountered it in its original context.

This ‘akosi’ figure will form part of the [Re:]Entanglements exhibition scheduled to open at the University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in April 2021. As such, one of the conservation treatment aims was to ensure that, after 111 years, all three elements could once again be put back together for display.

An initial condition assessment of the object revealed several instances of damage:

- The wooden figure was covered in surface dirt and dust, and debris from insect activity.

- There was a through crack in the left wrist that severed it completely from the rest of the arm.

- The left foot had suffered extensive insect damage and was largely missing.

- The feather had also suffered extensive insect damage and was dirty, broken and misshapen. There is a corresponding hole on the right side of the figure where presumably a second feather used to be, but this is totally missing now.

- The cane and plant fibres in the cowrie shell headdress had become brittle, inflexible and unable to support the weight of the cowries. The headdress was made up of five tendrils. Of these, one was very short and another slightly shorter than the other three. There were also loose cowries bagged separately, indicating that perhaps originally there were only four strands and that when one had broken, the broken end had been reattached at the top.

We had to decide what level of treatment would be appropriate for each of these issues, and we were able to do so thanks to the possibility of referring to the historic photograph.

Close examination of the photograph revealed:

- That the surface dirt present was most likely museum dirt, although there were areas of dirt in the original figure the ghost of which could still be seen in the object. For this reason, it was decided to sensitively clean the wooden elements with only dry cleaning methods and to avoid the use of any solvent which may have removed more than simple surface dirt. In this way we could guarantee the cleaning of recent dirt but leave behind any deposits that may be related to the use or beliefs associated with the figure.

- The through crack on the wrist can already be seen in the historic photograph. Wood is anisotropic and moves in different directions in reaction to changes in humidity and temperature. Cracks of this type often occur through movement tensions in green wood that has not been properly allowed to dry before being carved. That the crack can already be seen in the historic photograph suggests that the object may have already been in existence for some time before Thomas acquired it. This information clarified that it would be totally inappropriate to fill that crack because it has been there for over 100 years and allowed the wood to move in response to environmental changes without further stresses, but also because a fill would have obscured important information about the object history.

- The insect damage caused to the left foot can also be seen in the historic photograph, although perhaps it was not as extensive then. Because of this, only minimal intervention fills were done to support any areas at risk. The fills were done with long fibre Japanese tissue paper (a very thin but strong paper) and a cellulose based adhesive that was sympathetic to the nature of wood. Watercolours were used to tint the Japanese tissue paper to blend the fills with the surrounding wood. The insect damage visible in the historic photograph again seems to indicate that the object was not new when it was acquired by Thomas.

- Two feathers are visible in the historic photo, one on either side. The remaining feather was repaired with fills done in the vane to strengthen it and realign it back to its original shape. The feather was also dry surface cleaned and also cleaned with solvents to restore its shape as much as possible.

- It was clear from the historic photos that only four strands of similar length were originally present as part of the cowries headdress, confirming that the two shorter strands were originally one and that the loose cowries were probably part of this broken strand. That information, together with the need to strengthen the cane so that it would be able to support the weight, allowed us to take quite an interventive approach: the fourth strand was lengthened with the lose cowries, and all the strands were stabilized by threading them with nylon fishing wire, to support the weight instead of the fragile cane threading. Tinted epoxy buttons were made matching the colour of the cowries to serve as stoppers for each of the cowrie strands. Three nylon lengths were braided to create a stronger wire that was used at the top of the object to connect the nylon fishing wire used on the cowrie strands, and to allow the headdress to sit again on top of the figure during exhibition.

The conservation treatment given to this object is a good illustration of the decision making processes we conservators go through as part of our work. Ethical treatment decisions were made in this case because we were seeking to stabilise the object and bring it to the condition that best reflected its values and affordances. This meant different approaches to different areas of the object: minimal intervention was adopted for most elements whereas the headdress required a far more interventive solution to allow the object to be displayed back together and have its integrity restored.