A video introducing some of the work we have been pursuing in the University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology stores by George Emeka Agbo, the project’s postdoctoral research fellow.

Month: September 2018

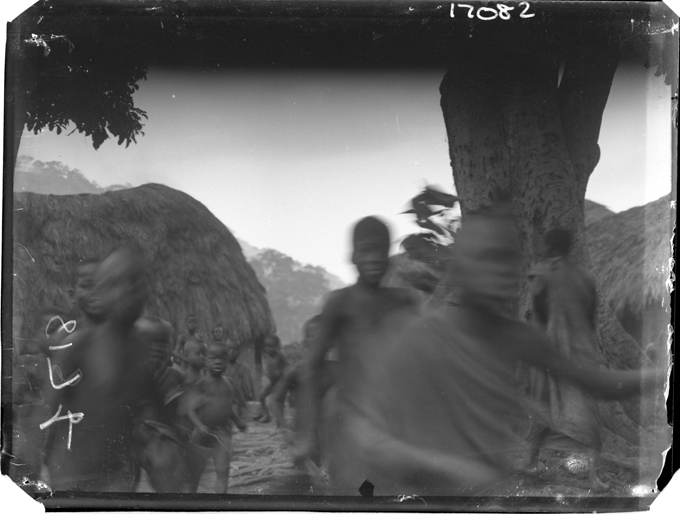

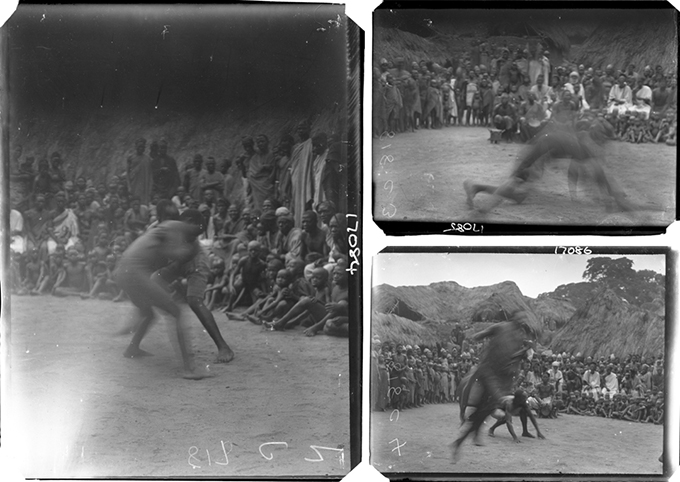

Otuo wrestling festival, July 1909

The first phase of the [Re:]Entanglements project has been focusing on researching the archives and collections assembled during Northcote Thomas’s anthropological surveys in Southern Nigeria and Sierra Leone. After the surveys, the collections were dispersed and they are now scattered across many institutions, including the University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, the Royal Anthropological Institute, the British Library Sound Archive, the UK National Archives, and National Museum, Lagos. One of the exciting aspects of this research is to reassemble the disassembled documents, photographs, sound recordings and artefacts relating to a particular event that N. W. Thomas documented.

Here, for example, we bring together photographs, sound recordings and an object that can be associated with an account of a wrestling festival that Thomas attended on 12-13 July 1909 in the North Edo town of Otuo (spelled Otua by Thomas). This written account was found in a bundle of typed up notes from his first tour, perhaps fragments of an early draft of his Anthropological Report on the Edo-speaking Peoples of Nigeria.

At Otua I witnessed a wrestling festival called Ukpesoda, said to have been ordered by Osa.

At 8.30 in the morning the road to the market but not the market itself was swept by boys who had not yet joined otu [an age-set]; then they plucked leaves from any tree on the road & headed by two boys carrying brooms marched through the town & back to the square.

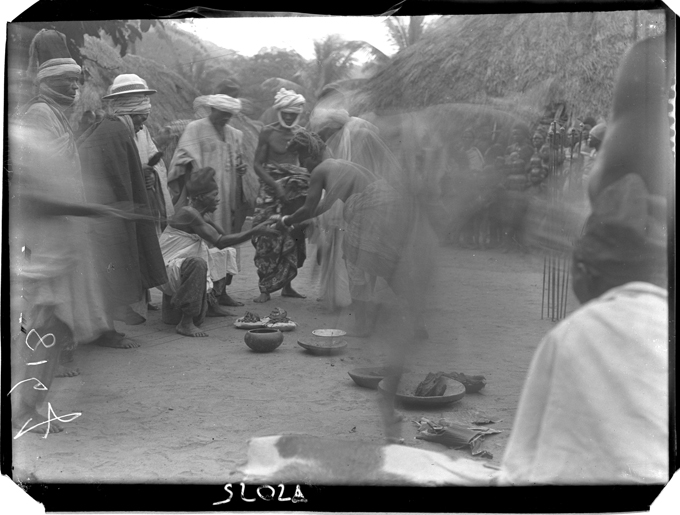

In the afternoon a sacrifice was offered to the ground, euelekpa, by four of the king’s company, while the other chiefs looked on. The main share in the ceremony was borne by Eidevri (A) & Omorigie (B). A said: I salute the whole town; now is the time for our feast; B replied: the whole town thanks you.

A said: The king gets more fufu than others. The king replied: I thank you for seeing that it is all right. The fufu was provided by the king & three chiefs.

A & B then washed their hands & stood on either side of the stone of sacrifice. B brought water & put the dish on the ground; A washed his hands over the stone; B brought fufu & handed it to A & then put soup & four pieces of meat in the fufu dish. A put it on the ground close to the stone & they repeated this operation four times, once for each set of fufu. Then A & B stood aside, saying: We have finished, come & eat.

Then small boys lined up some ten yards away, rushed in, seized the fufu & took it away from the square to eat.

On their return A & B began to divide the fufu for the different companies. A cut the fufu horizontally, leaving some in the bottom of the calabash for the chief who provided it & putting the other slices on leaves on the ground. Then he took a knife & cut the fufu on the leaf & B gave to each company. The head took it & summoned the others. The people who are not yet in a company also get a portion, which is handed to the firstcomer after the order is given.

The meat was then cut up; the four chiefs got a piece each & A took the remainder home; it was divided on the following day.

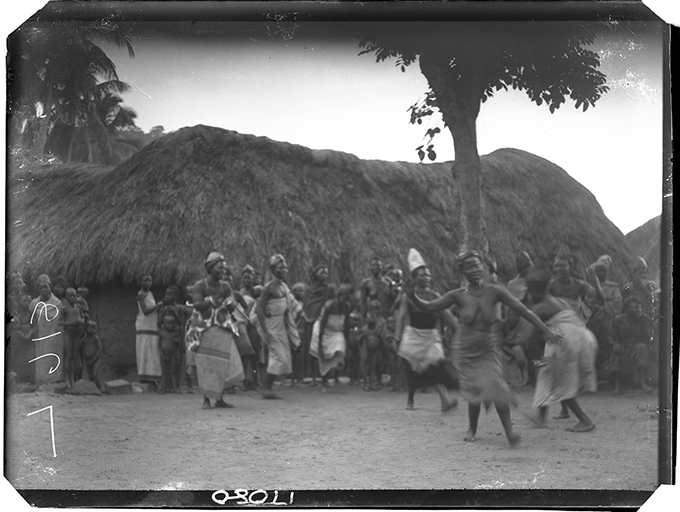

The sacrifice over, the women began to dance & sing for joy; two performed to the song of the others; then all raised their hands & shouted.

‘Otua women’s song, July 13th 1909’. NWT 169, BL C51/2449.

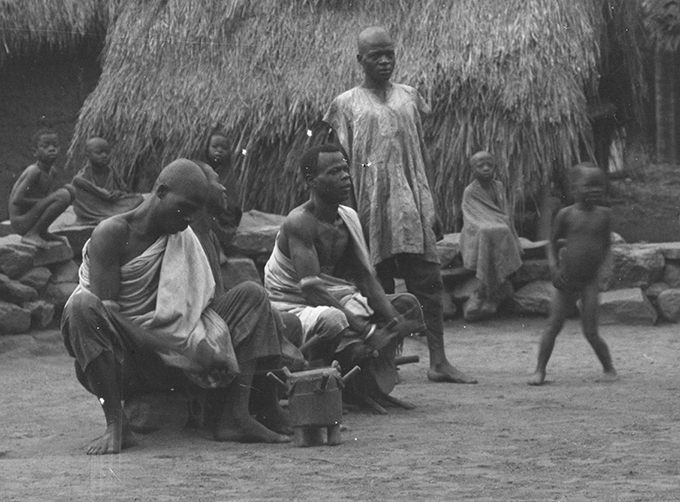

On the following morning three drummers appeared on the square at 7.30 AM with three kinds of drums called alukpe, ozi & adoka.

Drumming recorded by N. W. Thomas in Otuo, July 1909. NWT 156, BL C51/2268.

As soon as the people collected the wrestling began. Men hopped round the circle as a challenge & the victor hopped around afterwards.

Anyone familiar with Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart will recall the significance of wrestling in southern Nigerian society. We might imagine the scene in Otuo as being not unlike that evoked by Achebe:

The drummers took up their sticks again and the air shivered and grew tense like a tightened bow … The wrestlers were now almost still in each other’s grip. The muscles on their arms and their thighs and on their backs stood out and twitched. It looked like an equal match. The two judges were already moving forward to separate them when Ikezue, now desperate, went down quickly on one knee in an attempt to fling his man backwards over his head. It was a sad miscalculation. Quick as the lightning of Amadiora, Okafo raised his right leg and swung it over his rival’s head. The crowd burst into a thunderous roar. Okafo was swept off his feet by his supporters and carried home shoulder-high. They sang his praise and the young women clapped their hands.

Since the N. W. Thomas collections are in different physical locations, it is only through digital technology that we can bring them together in one space, reuniting sound, image and object. Bringing together these materials seems simple enough, but actually involves painstaking archival and collections-based research. Each institution has accessioned these materials using its own numbering system, and it has been necessary to reunite them using Thomas’s own original numbering systems, relying on the scratched numbers on the edges of photographic negatives, Thomas’s spoken ident at the beginning of sound tracks, and associating Thomas’s collection numbers with his object catalogues. This is further complicated by the fact that there is no straight-forward documentation of Thomas’s itineraries, recording what he did where, and what he collected, photographed and recorded.

Ibillo’s Ugolo mask, Guest blog by Jean Borgatti and Wendy Emmanuel Adejumoh

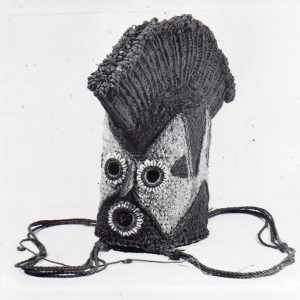

Northcote Whitridge Thomas collected this helmet mask from Ibillo in 1910, towards the end of his first tour in Edo-speaking areas of Nigeria (Figure 1). Ibillo, one of the Okpameri groups in what is now Akoko-Edo Local Government Area of Edo State (then part of what was called Kukuruku), continues to use this type of mask in its age-grade festival called Ikpishionua, held approximately every 7 years. At the Ikpishionua festival the mask appears under the name of Ugolo, while during smaller annual festivals it appears as Uvbono.

I photographed this mask at University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in 1969 (Figure 2) as part of a feasibility study for field research among the peoples of Edo North that I began in 1971 – though Ibillo did not figure in that early field research. When I returned to Nigeria in 2015, over forty years later, I did begin to do additional research in Akoko-Edo, and visited Ibillo at that time. When I showed my photograph to an elder and group of age-grade members, they cautioned me not to show it to women since it was in the ‘production’ stage: that is, without costume and without the line of feathers inserted into the sagittal crest, as can be seen in a video made by Emmanuel Concept Video Productions of the Ikpishionua festival in 2015 (Figure 3). I was able to obtain screenshots of various masquerades from this video and Professor P. D. Ogunnubi of Odo Quarter and age group representatives identified these for me, giving a brief explanation for each one. Subsequently, an art history student from the Department of Fine and Applied Arts at the University of Benin and an Ibillo indigene, Wendy Emmanuel Adejumo, wrote his honors thesis on the masquerades (Adejumo 2017). This blog entry draws on our shared findings.

The term ‘Okpameri’ dates from the mid-19th century and was the result of a number of neighboring villages solidifying their coalition against Nupe slave-raiding (Orifah n.d.). Okpameri has also come to mean ‘We are one’, though it was not a term used much before the middle of the 20th century. Okpameri includes 23 towns and villages: Aiyegunle (Osi), Anyaoza, Bekuma, Dangbala, Ekor, Ekpe, Ekpesa, Ibillo, Ikiran-Ile, Ikiran-Oke, Imoga, Makeke, Lampese, Ogugu, Ogbe, Ojah (Ozah), Ojirami-Afekunu, Ojirami-Dam, Ojirami-Kpetesshi, Somorika, Ugboshi-Afe, Ugboshi-Ele and Unumu (Orifa n.d.). Ibillo’s population as recorded in the 2006 census was 24,303 (Ojeifo & Esaigbe 2012). It consists of four kinship-based quarters. Listed in order of seniority, these are: Eku/Odo, Uwhosi/Illese, Ekuya and Ekuma/Uzeh. Ibillo’s headship rotates among these quarters. All celebrate an age grade festival approximately every 7 years, and in the past they all celebrated on the same date. In recent times, however, the quarters have staggered their celebrations to maximize local attendance. There is some controversy over this since some believe Ibillo could make ‘tourist capital’ from the festival if they celebrated together.

Though held annually to purify the community and foster community identity, the festival is celebrated in its most elaborate form approximately every 7 years when a new male ‘age group’ is formed. In this way, it resembles the situation described in a previous blog on Otuo, a community on the border of Akoko-Edo and Owan Local Government Areas, which Northcote Thomas also visited and where he photographed masquerades associated with an age-group festival called ‘Eliminia’.

Although Professor Ogunnubi identified the mask collected by Thomas as ‘Ugolo’, Northcote Thomas recorded its name as ‘Ofuno’. This appears to be a misspelling. The proper spelling should be ‘Ubvono’ or ‘Uvono’. Ubvono is only celebrated in the interval between Ikpishionua festivals, suggesting that Thomas was not in Ibillo during a year when an age company was formed. Local respondents suggested that the mask was likely to have been made in Ekuya quarter, a community known for the thick weaving of the Ugolo mask form. The Ugolo, Ubvono and other woven masks are essentially the same, differentiated only by their context of use and the ‘finishing’ or decoration of the mask. For Uvbono, the Ugolo mask would have its feathers fixed differently from when it performs during Ikpishionua, and it does not perform fully in Ubvono because Uvbono is not a ‘serious’ festival, but more entertainment oriented. A nine-day festival, its function is to keep the community busy and engaged.

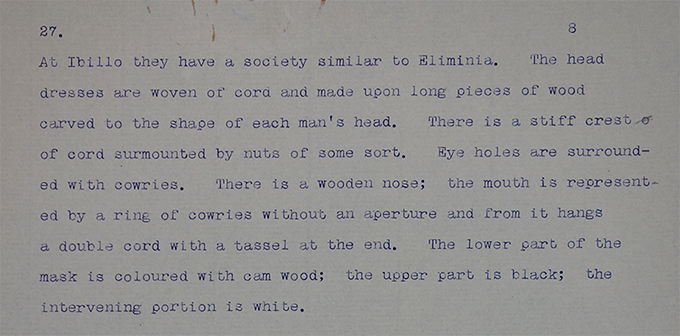

A description of the mask may be found in Thomas’s typed-up fieldnotes (Figure 4). He writes that, in Ibillo, ‘headdresses are woven of cord and made upon long pieces of wood carved to the shape of each man’s head. There is a stiff crest of cord surmounted by nuts of some sort. Eye holes are surrounded with cowries. There is a wooden nose; the mouth is represented by a ring of cowries without an aperture and from it hangs a double cord with a tassel at the end. The lower part of the mask is coloured with cam wood; the upper part is black; the intervening portion is white’. (Note that the tasselled cords extending from the mouth have become detached and lost, though one can see evidence of where it was attached.)

Many of the characteristics Thomas described can still be found in the Ugolo masks that are made in Ibillo today. The colours include red around eyes and mouth as well as on the beak-like nose. They have sagittal crests dramatized by the addition of feathers. The feathers have not been identified, but it is possible that they include the tail feathers of a rooster since the head with its crest and beak represents the head of a cock. The body covering is made of the pith from the bark of any healthy tree with a thick bark. Once the bark is removed, it is left to soften in the river for some days to allow for easy separation of the inner part or pith from the bark. The pith is further washed to increase its pliability. The resulting material, emue, is used to create the fronds covering the masqueraders’ bodies as well as the fiber employed in weaving the masks themselves.

During the initial outing of the masquerades during the Ikpishionua festival, all the masqueraders wear cloth covers over the costume of fronds as illustrated in another screenshot from the Emmanuel Concept video (Figure 5). The cloth covers are only worn during the full Ikpishionua age-grade festival, and not during the minor annual festivals in intervening years. The cloth covers are also seen as a symbolic definition of women’s involvement in the festival when they have license to dance alongside masquerades without committing offense, contrary to other festival celebrations. Women and family members often wear the same cloth to indicate their relationship to a particular masquerader who may be one of the newly initiated or someone being promoted to another level – tacitly identifying him. As the festival progresses, the masqueraders abandon their cloth shawls, revealing their masks more clearly for the audience to appreciate.

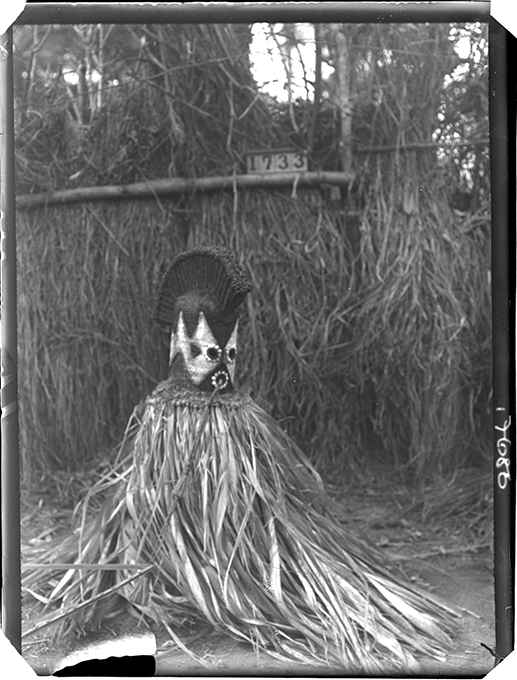

In 1910, Thomas also photographed a similar mask at rest in the masquerade stockade (ukpala or uyala) (Figure 6) where participants make their masks and prepare for the celebration of the festival in relative privacy, away from the gaze of women. This is also a place where those wearing masks can rehearse their dancing before coming out to display. The ukpala walls stand about 15 feet high and the interior space is as large as possible in the area allocated for its construction. It is a temporary structure with walls made of dry palm branches today as in the past.

During Ikpishionua, Ugolo represents the elders and chiefly ancestors of Ibillo. It plays the metal gong, elo, as it sings historical songs, eulogies and epics (welaku), communicating with the people in specific areas or quarters it visits, speaking in parables. It is one of the four main mask types seen today, and probably the oldest type, the others being Umueku, Ulele and Obibia. There are numerous minor masquerades too that use the basic knit or woven form displayed by Ugolo, often without the crest. These minor masks are created by the incoming age group, and they sport different caps or headdresses created to amuse the community, inspiring jokes and nicknames. Such names refer especially to the addition of the objects to the top of the mask, such as a pouch of ‘pure water’ (ame) for the ‘hawker of water’ and ‘water as life’ masks. The label ‘fish cold-room’ (ehwena) suggests the seller of meat or food, a female hair-do (zo ehwo eh bio za) depicts young females and their fashion, a woman’s head-tie or igaleh suggests elderly women, mirrors (ugbegbe) represent eyes in the round as well as reflection, interpretation, or the foreshadowing of possibility. Costuming and accessories are meant to encourage women to make satirical comments on the masquerades. The festival is, after all, an ‘occasion for people of different ages – men, women and children – to work together creatively, making masks, costumes, musical instruments, engaging in body painting, and performing together as a community’ (Adejumoh 2017).

References

- Adejumoh, W. E. (2017) ‘Masquerades and other art forms of the Ikpishionua festival in Ibillo, Akoko Edo Local Government Area, Edo State’, unpublished BA thesis, University of Benin.

- Ibillo People Facebook page

- Orifa, S. O. (n.d.) ‘The linguistic situation and geography of Akoko-Edo Local Government Area, Edo State, Nigeria‘ (working paper)

- Ojeifo, O. & J. O. Eseigbe (2012) ‘Categorization of urban centres in Edo State, Nigeria‘, IOSR Journal of Business and Management 3(6): 19-25.