For 10 days in February 2020, the University of Nigeria, Nsukka hosted the third [Re:]Entanglements project exhibition to take place in Nigeria. The exhibition, ‘[Re:]Entangled Traditions: Nsukka Experiments with an Anthropological Archive’, was the culmination of a collaboration between the project and eleven artists associated with the famous ‘Nsukka Art School‘, as well as colleagues from the departments of Music and Linguistics.

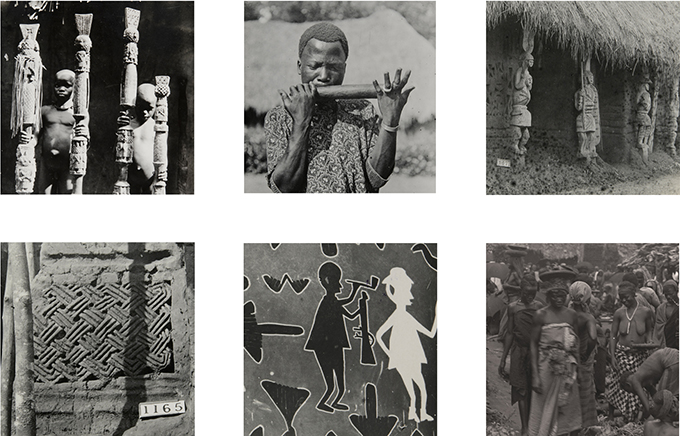

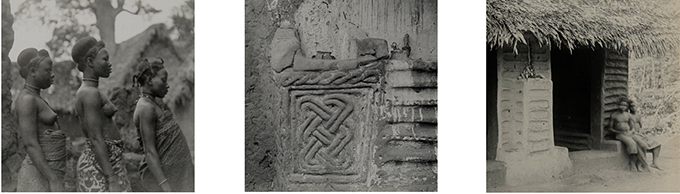

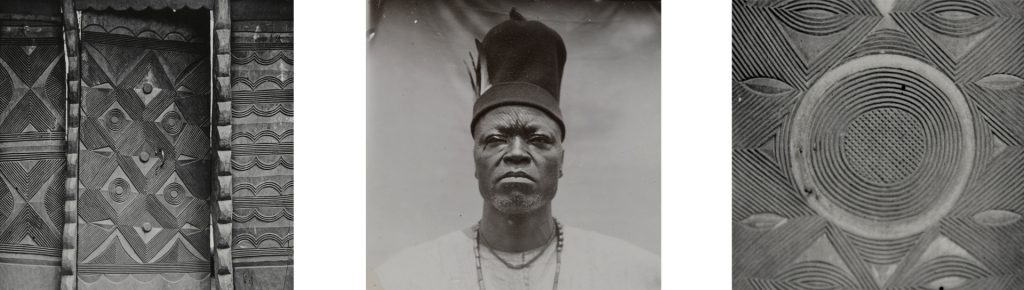

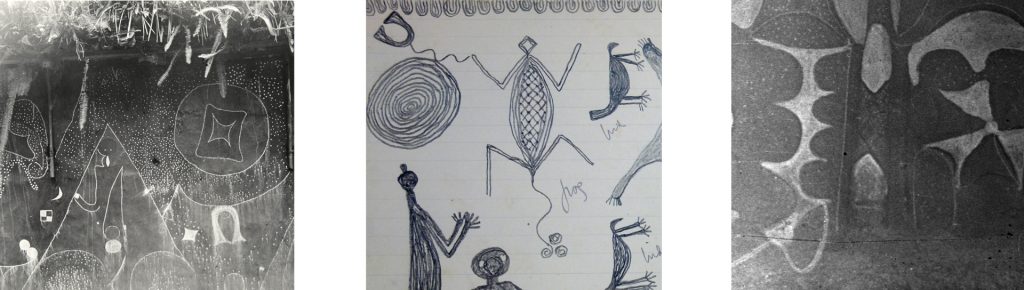

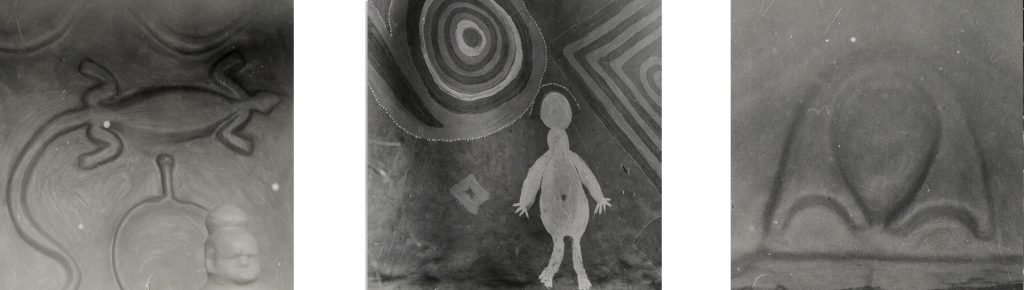

Nsukka’s Department of Fine and Applied Arts was established in 1961 by Ben Enwonwu and was one of the earliest departments of the University of Nigeria. The Department became famous in the years following the Biafran War (1967-70) when luminaries such as Uche Okeke, Chike Aniakor and Obiora Udechukwu began turning away from Western art traditions and finding inspiration in indigenous art, culture and philosophy. In particular a number of artists began rediscovering and experimenting with Igbo uli body and wall art traditions. Northcote Thomas‘s photographs are some of the earliest and most comprehensive visual documentations of uli wall paintings. This represents an important new reservoir of traditional uli work and, not surprisingly, a number of the participating artists drew upon these photographs in their contemporary works in different media.

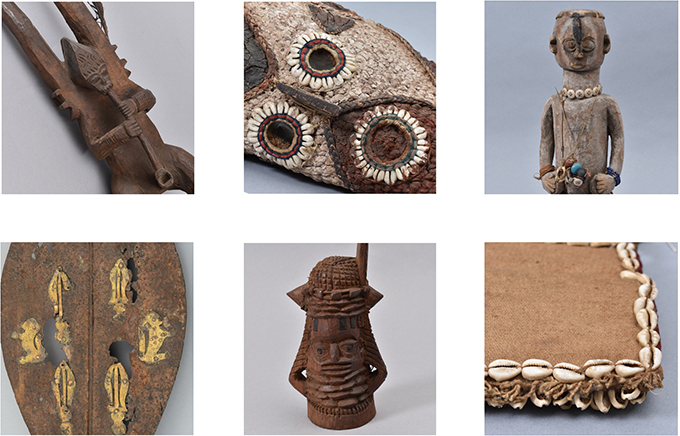

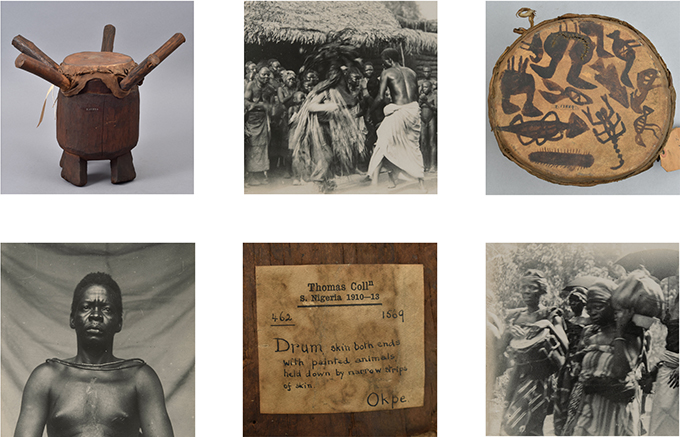

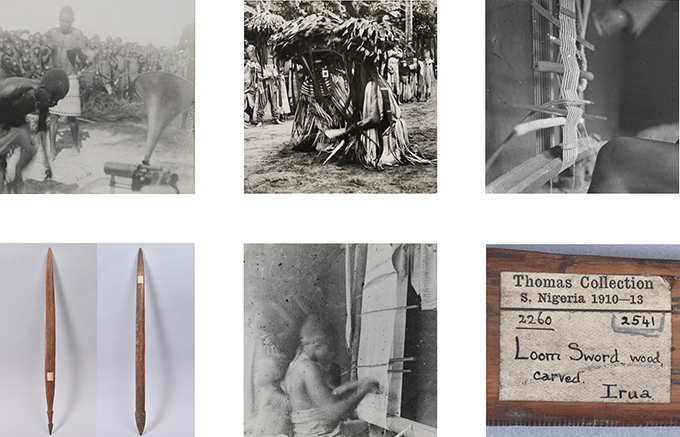

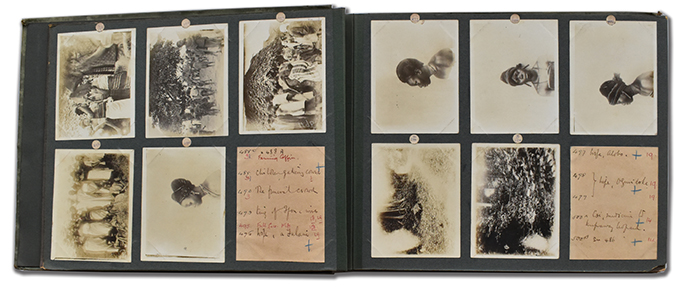

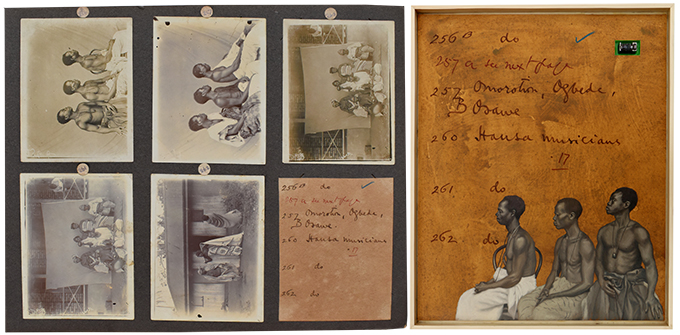

As with earlier exhibitions in Benin City and Lagos, the objective of the collaboration was to explore the ‘creative affordances‘ of the photographs, sound recordings and artefact collections produced during Northcote Thomas’s anthropological surveys in Nigeria between 1909 and 1913. As the leading university in the Igbo-speaking region of Nigeria, the Nsukka collaboration focused on materials assembled by Thomas during his second and third tours – those focusing on areas of what are now Anambra and Delta states.

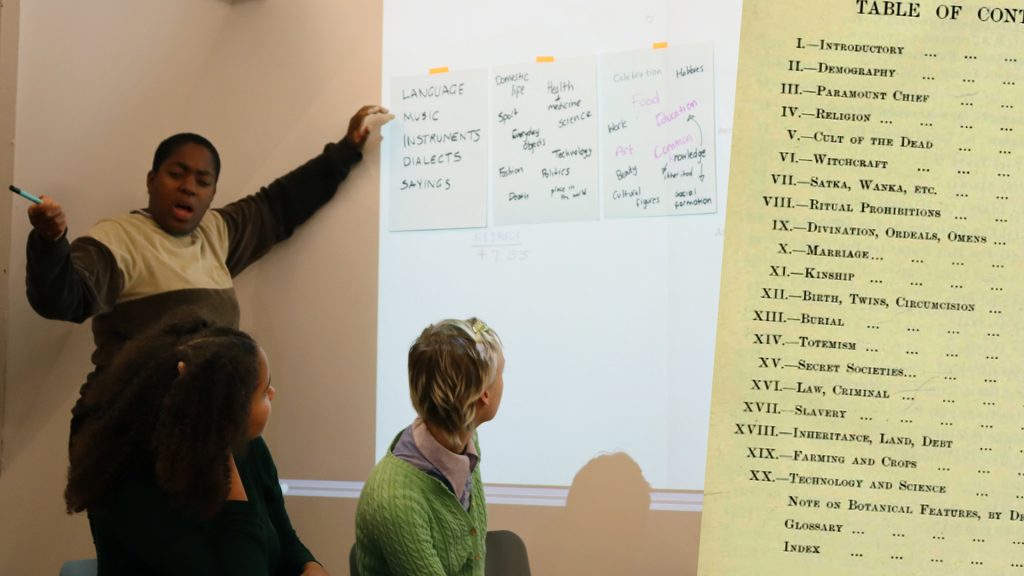

The collaboration began in 2018 with an open workshop to introduce prospective participants to the [Re:]Entanglements project and Thomas’s archival materials. Following a call to submit proposals, projects were given the go-ahead and provided with a budget to cover materials and expenses. A follow-up workshop took place in 2019 in which participants presented their works-in-progress.

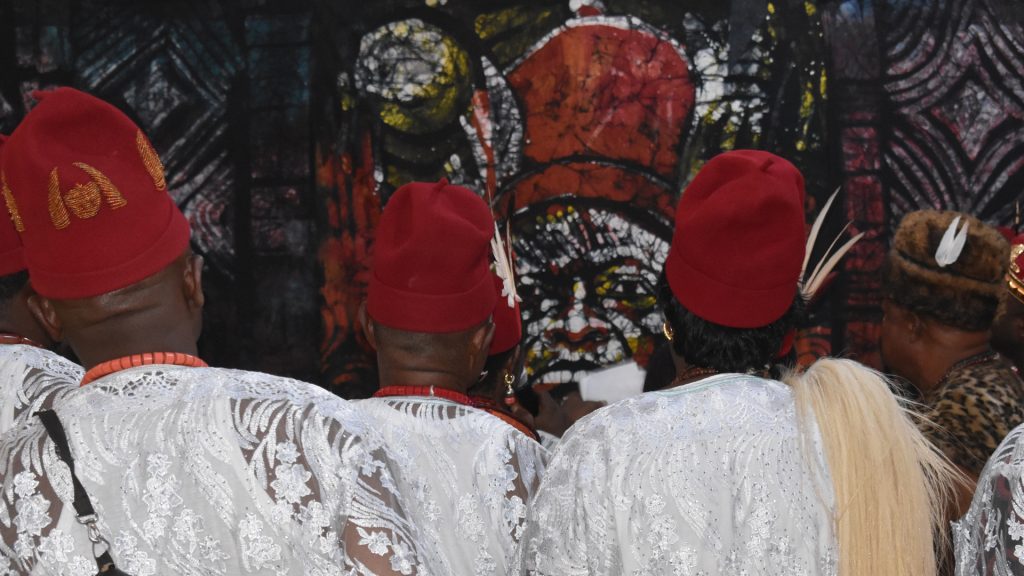

The exhibition was opened by HRM Obi Martha Dunkwu, the Omu Anioma, a well known female chief from Delta State. The Omu has been a close friend of the [Re:]Entanglements project since our visit to Okpanam. In a very moving speech Obi Martha Dunkwu told the story of how Northcote Thomas’s 1912 photograph of the Omu of Okpanam settled a dispute in which the Omu’s right to wear the red cap of chiefly office had been contested. The story illustrated powerfully how these colonial era archives could intervene in contemporary issues. The Omu explained that this was no small matter.

There was a lively and well-attended opening ceremony in which each of the artists presented their work to the Omu and her entourage. The event was accompanied by a traditional music ensemble made up of students of the Department of Music under the direction of Ikenna Onwuegbuna, Head of the Department of Music. The music included versions of songs originally recorded by Northcote Thomas himself.

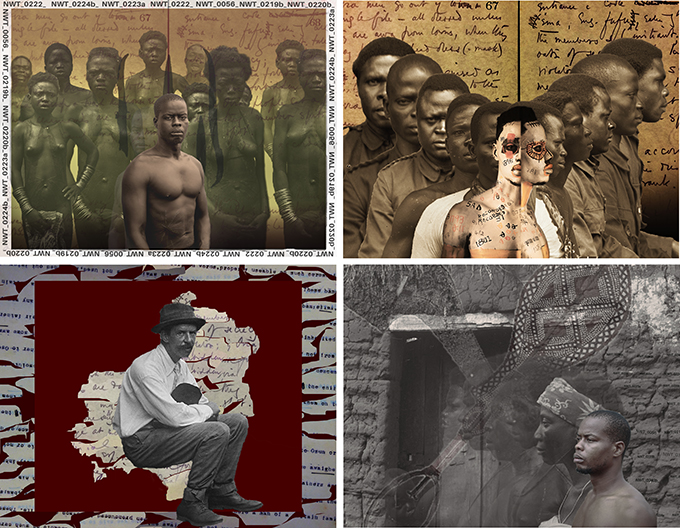

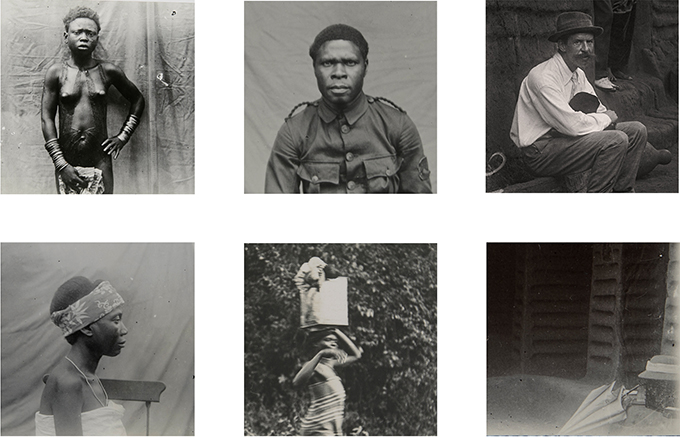

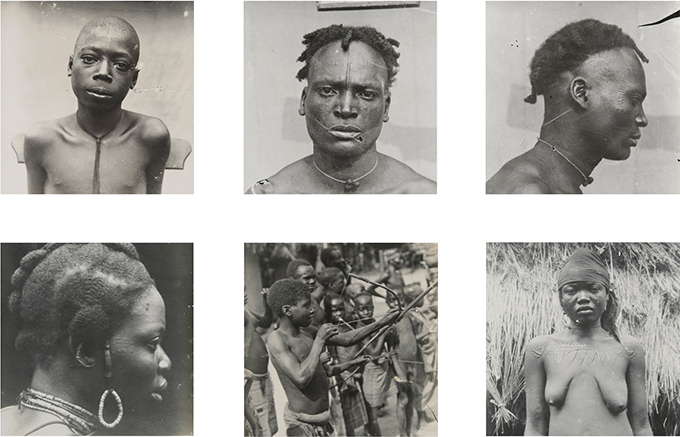

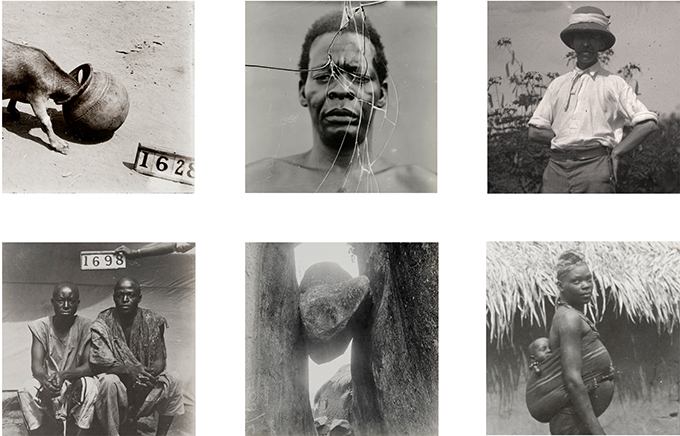

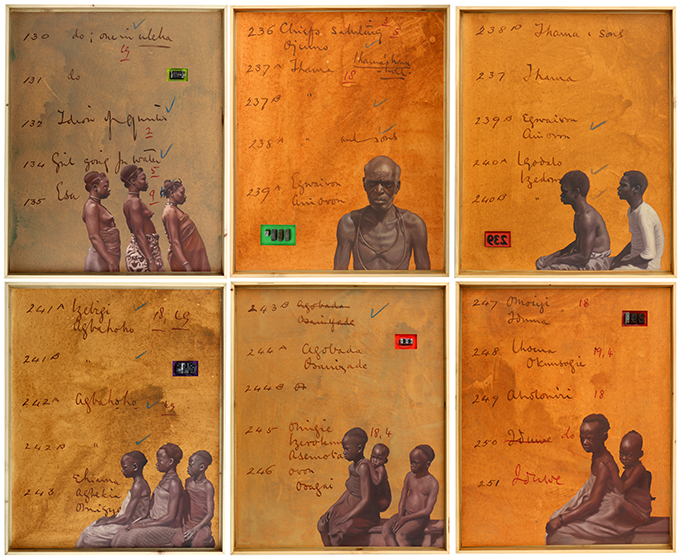

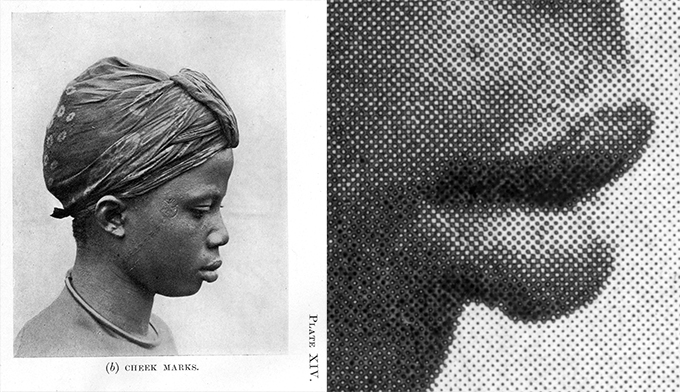

In ‘[Re:]Entangled Traditions’, each of the artists took on a particular Igbo cultural ‘tradition’ – uli body and wall painting, ichi scarification, hair-styles, clothing, wrestling – that featured in Northcote Thomas’s photographic archive. These visual references formed the basis of their experiments. In the following sections we present each of the participating artists’ works juxtaposed with some of the Northcote Thomas photographs that inspired them. The musicological and linguistic contributions to the exhibition are the subject of separate blog posts (see Revisiting some Awka folksongs).

Chijioke Onuora, Ezeana Obidigbo

Chijioke Onuora is Head of the Department of Fine and Applied Arts at University of Nigeria, Nsukka. He initially trained at Nsukka as a sculptor in the early 1980s and was taught and influenced by many of the leading figures of the ‘Nsukka School’. Through this training he came to appreciate the traditional Igbo art that was fast disappearing in his village in the Awka area and made studies of shrine carvings. For his PhD in Art History, Onuora made an extensive study of ikolo drums, including their sculptural, musical and socio-cultural dimensions.

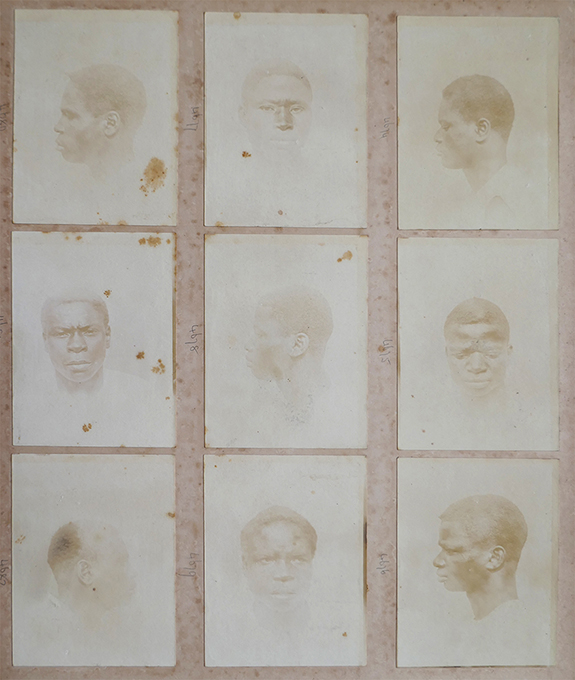

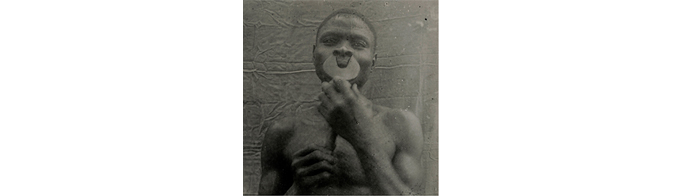

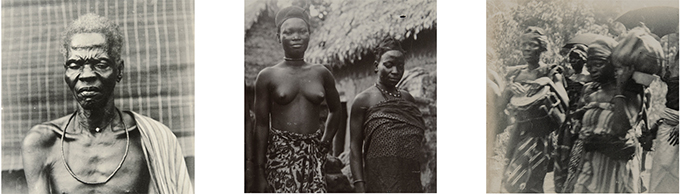

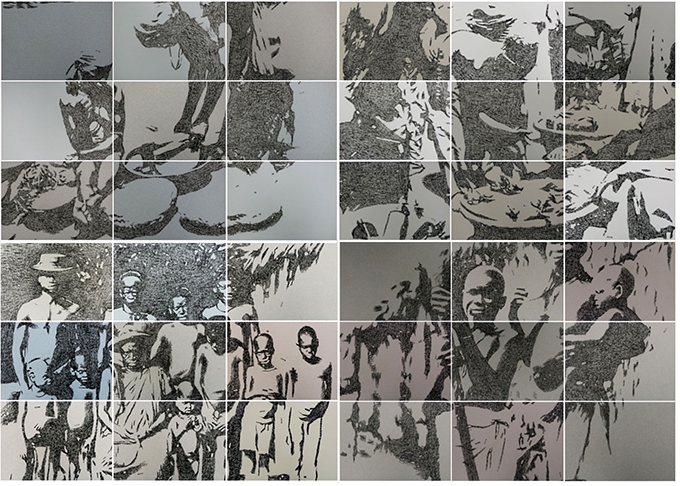

Onuora works across many different media, though he regards drawing – the line – as fundamental to all these. For the ‘[Re:]Entangled Traditions’ collaboration, he was particularly interested in re-engaging with Igbo ichi scarification, with its linear markings. As a child, Onuora encountered men – and, indeed, one woman – bearing these marks. Now he believes there is just one elderly man in his village who has still has the marks.

When he was introduced to the Northcote Thomas archives as part of the [Re:]Entanglements project, he was struck by the large number of photographs of men of all ages with ichi scarification. This has inspired him to focus on ichi in his ongoing work.

Onuora produced two monumental batik works for the ‘[Re:]Entangled Traditions’ exhibition. The first is a portrait of Ezeana Obidigbo of Neni, originally photographed by Thomas in 1911. Onuora’s village was close to Neni and his grandparents walked every week to the Oye market there – the scene of some of Thomas’s most memorable photographs. The Umudioka community of Neni were specialist surgeons who travelled throughout the region making the ichi marks.

Onuora’s second batik, ‘Nze na Nwunye ya’, is based on a photograph taken by Thomas in Agulu of a mud relief sculpture of a male and female figure, and marks a return to Onuora’s earlier work on shrine figures. The male figure again wears the ichi scarification marks. In both ‘Ezeana Obidigbo’ and ‘Nze na Nwunye ya’, the central panel is flanked by two panels evoking traditional wood carving – symbols of prestige and status – also photographed by Thomas during his 1910-11 survey of what was then Awka District.

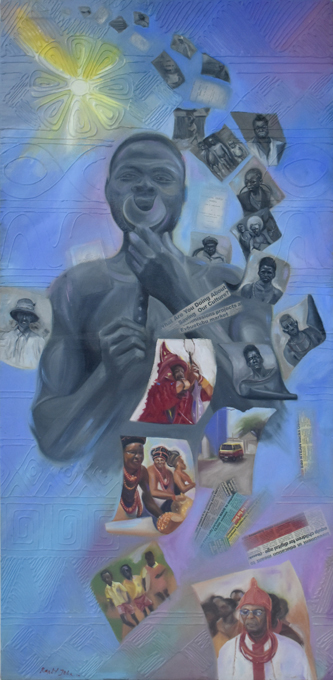

Chuu Krydz Ikwuemesi, Playing with Time and Memory

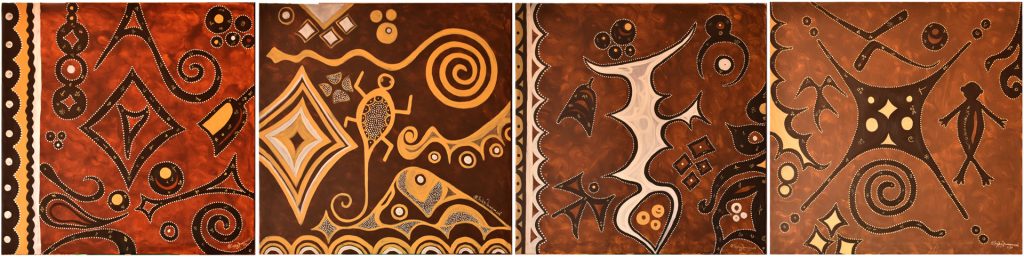

Chuu Krydz Ikwuemesi is a painter and Associate Professor in the Department of Fine and Applied Arts at Nsukka. He joined the Department as an undergraduate in 1987 and, like many students of his generation, was influenced by Uche Okeke and others who had rediscovered the uli painting tradition as a demonstration of Igbo cultural resilience, first as an indigenous response to European colonialism and subsequently in the wake of the traumatic defeat of the Nigerian Civil War. Ikwuemesi was encouraged to continue the work Okeke’s generation had begun and to conduct research with the last generation of women who created uli wall paintings in the traditional setting of the village.

Although much of Ikwuemesi’s work is more overt in its political engagement, providing commentary on the violence and corruption of contemporary Nigeria, alongside this, he continues to draw upon uli explicitly in his paintings. This he sees as a form of cultural activism. In particular, Ikwuemesi is keen to promote the popularisation of uli design, so that it reaches beyond elite art audiences and collectors, and returns as a popular form.

For the ‘[Re:]Entangled Traditions’ exhibition, Ikwuemesi drew upon Northcote Thomas’s photographs of uli wall paintings, merging motifs and linear forms from different locations, to produce a series of four acrylic paintings on canvas. The title of the series, ‘Playing with Time and Memory’, reflects both the long history of uli painting among Igbo-speaking people and his own part in that history.

Exploring Thomas’s photographs of uli wall painting, Ikwuemesi was struck by the continuities and changes in the art form. Despite the ruptures of colonialism and war, he celebrates the resilience of cultural traditions, how people continue ‘to do old things in new ways’. ‘Colonialisation’, he argues, ‘did not take away the soul of the people or the soul of their culture’.

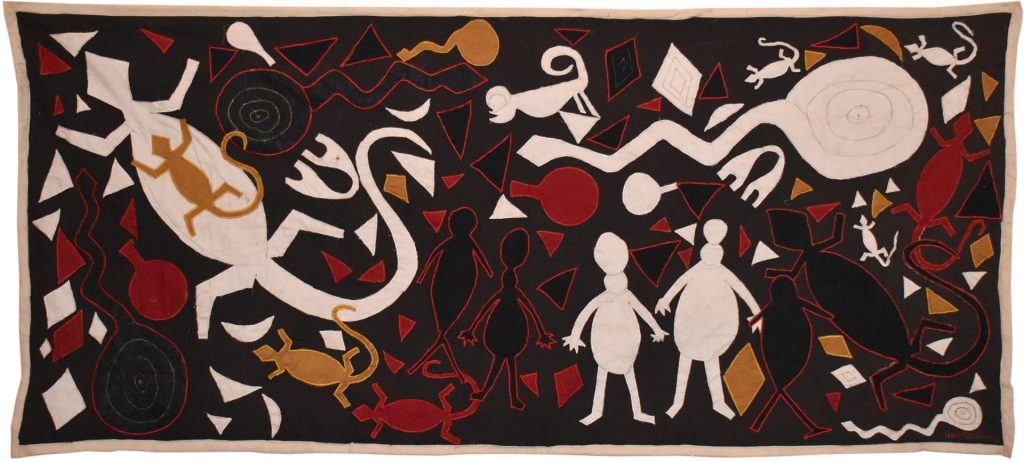

RitaDoris Edumchieke Ubah, Igbo Kwenu

RitaDoris Ubah is a Lecturer in Textile Art. She completed her BA, MFA and PhD all at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. Ubah’s aunt was herself a traditional uli artist. When Ubah started teaching at Nsukka, she realised that while uli traditions had been incorporated into other forms of contemporary art practice, including painting, ceramics and other graphic arts, they had not been explored in textiles. Thus Ubah was keen to bring uli into the curriculum, whether through weaving, embroidery, knitting or appliqué.

Ubah was particularly excited to discover the rich historical documentation of uli in Northcote Thomas’s photographs. As well as inspiring her own work, she has introduced her students to the archive and it now the subject of various class assignments. She describes the photographs as a ‘landmark resource’ and explains that every student passing through Nsukka is taught about it.

For the ‘[Re:]Entangled Traditions’ exhibition, Ubah produced several works, including a large appliqué panel entitled ‘Igbo Kwenu’, a second appliqué of a masquerade figure photographed by Thomas, and fashion collection featuring uli motifs from Thomas’s photographs. Ubah is particularly interested in the history of uli as a women’s art form, originally painted on the body. (The word uli comes from the plant from which the dye is made.) Ubah’s fashion collection, which was worn by models at the exhibition opening, represents an interesting return of uli to ‘clothing’ the body.

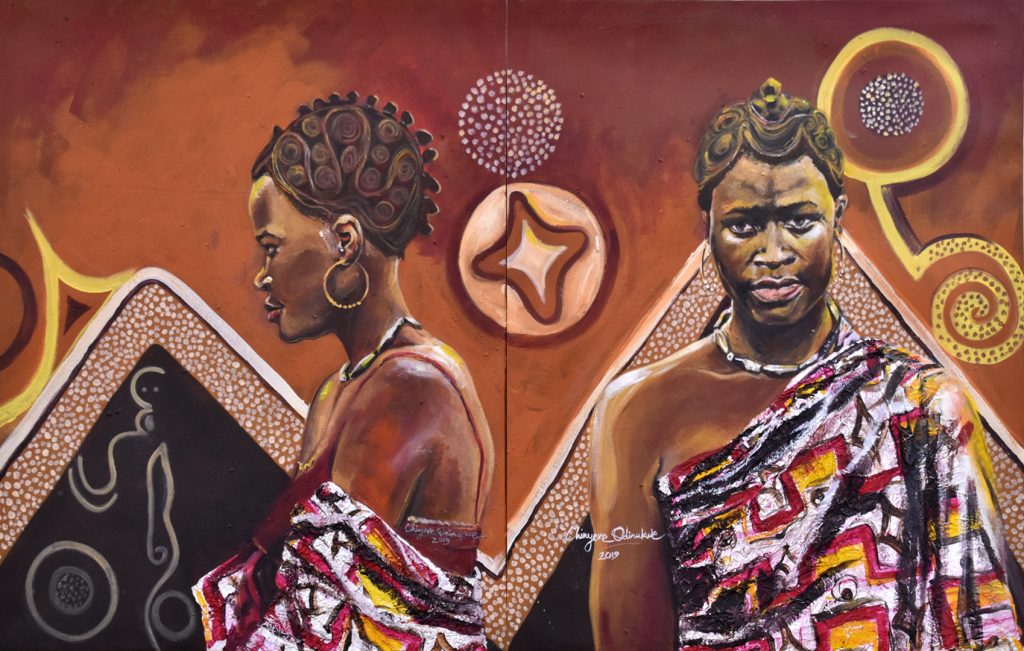

Chinyere Odinukwe, Akwamkosa Achalugonwayi

Chinyere Odinukwe took her BA and MA in the Department of Fine and Applied Art, Nsukka. She works mainly with acrylic paint on canvas, but also incorporates other materials in her work, notably salvaged plastics and metal foils.

For her [Re:]Entanglements project, Odinukwe wanted to juxtapose the historical and the contemporary by transforming the appearance of a woman named Nwambeke, photographed by Thomas in Nibo in 1911. (Odinukwe’s maternal home town is Nibo.) In order to do this, Odinukwe subtly altered the Nwambeke’s dress and jewellery – adding earrings, make-up and bra-top, for instance. In particular, she transformed her wrapper from a locally-made plain cotton garment (akwamkosa) into a dazzling contemporary fabric.

Odinukwe replaces Thomas’s plain photographic backdrop with a background inspired by one of Thomas’s photographs of uli wall painting.

In re-imagining Nwambeke as a modern Nigerian woman, albeit one framed by her indigenous culture, Odinukwe draws attention to the transformed place of women in Nigerian society today. Odinukwe says that she has given this woman her freedom. She observes that, even today, some people are enslaved in their different ways of life, whether religiously, politically or pyschologically. Odinukwe argues that we should not be chained by our traditions.

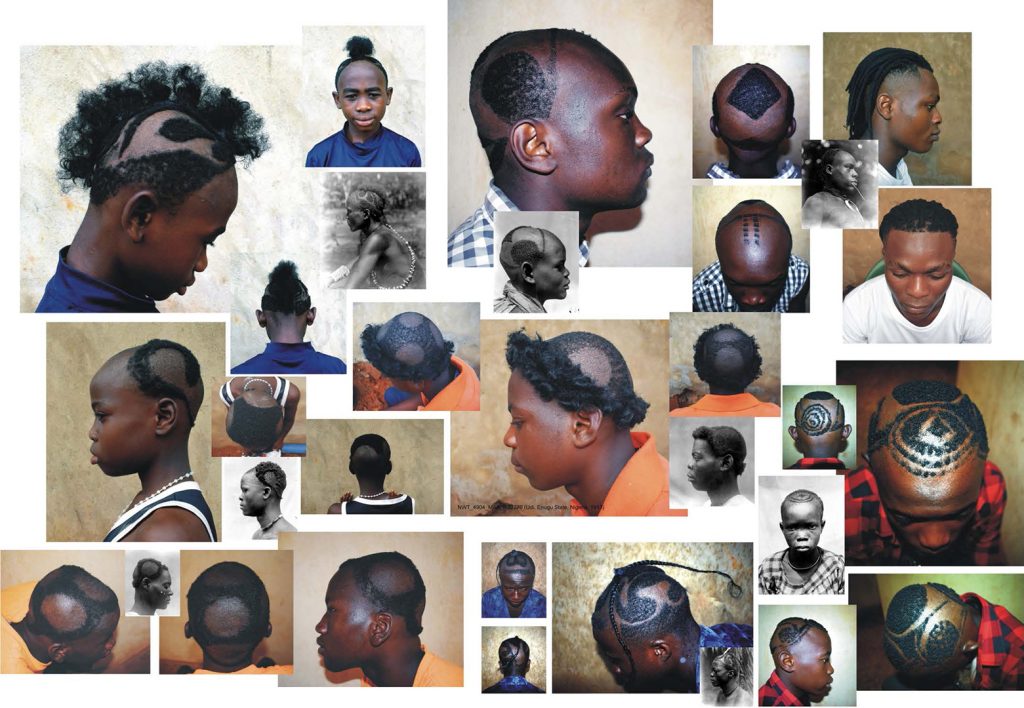

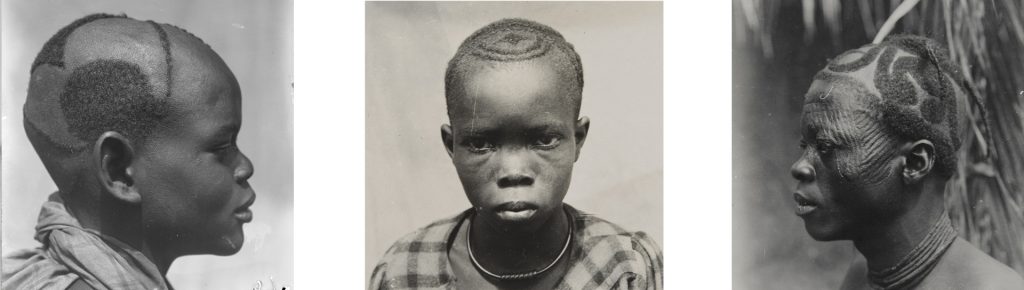

Chikaogwu Kanu, Isi Mgbe Ochie

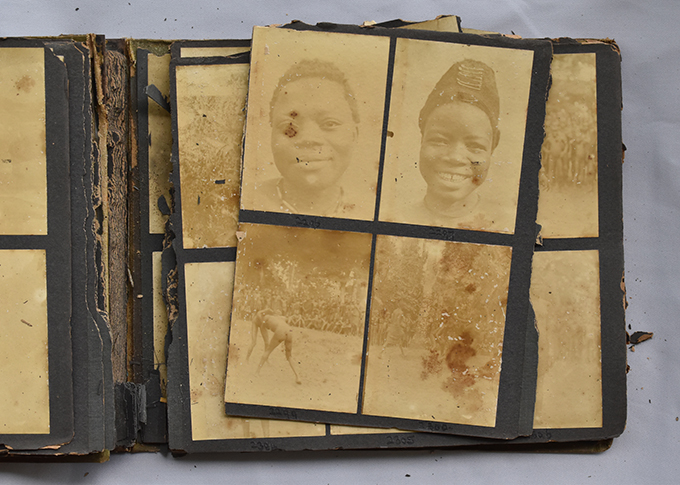

Chikaowu Kanu trained at Nsukka as a sculptor. He is now pursuing a PhD in Art History, while continuing to develop his skills as a photographer, videographer and graphic designer. Familiar with the Nsukka School’s long-standing engagement with traditional uli art, Kanu was impressed by another form of body art that was very evident in Northcote Thomas’s photographs – hair dressing.

In his project for the ‘[Re:]Entangled Traditions’ exhibition, Kanu sought to recreate some of the hairstyles that Thomas photographed. This proved to be a challenging task. It was not easy, for example, to find models willing to have their hair dressed in such remarkable styles. Others – barbers and models alike – assumed that Kanu would make lots of money from the photographs he was taking and thus demanded high fees that Kanu could not pay. Eventually, however, Kanu succeeded in collaborating with barbers and models, and displayed the results as a photo-montage in the exhibition. Kanu’s display drew a great deal of interest from visitors.

Ngozi Omeje, Eriri ji obele

There is a long tradition in ceramics and installation art at the Department of Fine and Applied Arts at University of Nigeria, Nsukka, associated with artists such as El Anatsui and Ozioma Onuzulike. Ngozi Omeje is foremost in the younger generation of ceramicists at Nsukka. In 2018, when the [Re:]Entanglements project collaboration with Nsukka began, she was in the middle of producing work for her highly successful exhibition, ‘Connecting Deep’, at the Centre for Contemporary Art in Lagos.

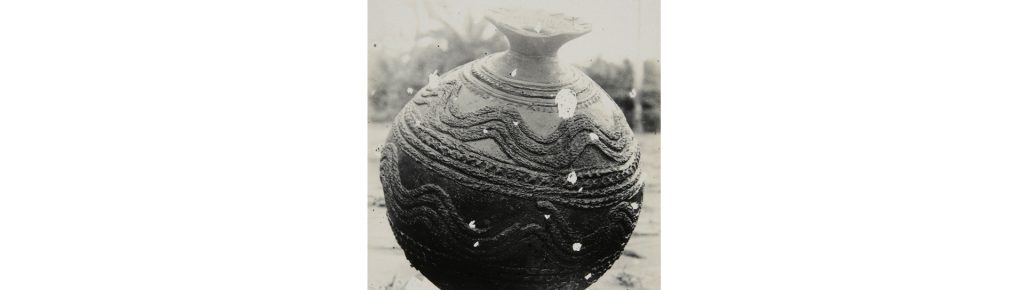

Omeje creates sculptures by suspending small clay pieces – miniature cups, leaves, rings, balls, etc. – on nylon threads. Often her works are of monumental proportions. For the ‘[Re:]Entangled Traditions’ exhibition, Omeje echoed the form of an elaborated decorated clay pot photographed by Northcote Thomas by suspending miniature leaves made from clay. On the one hand, her use of leaves fashioned from clay allowed her to follow the form of the linear patterns on the pot; on the other hand they are expressive of the temporality of the archive – the play of ephemerality and permanence.

The title of Omeje’s piece, Eriri ji obele, refers to an Igbo aphorism – ‘the string that holds the pot’ (or, more correctly, ‘the string that holds the calabash’). Our lives are in God’s hands.

Chukwunonso Uzoagba, Ogu Mnwere Onwe

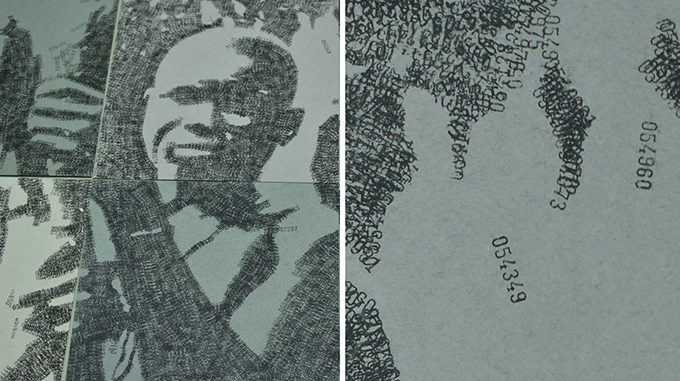

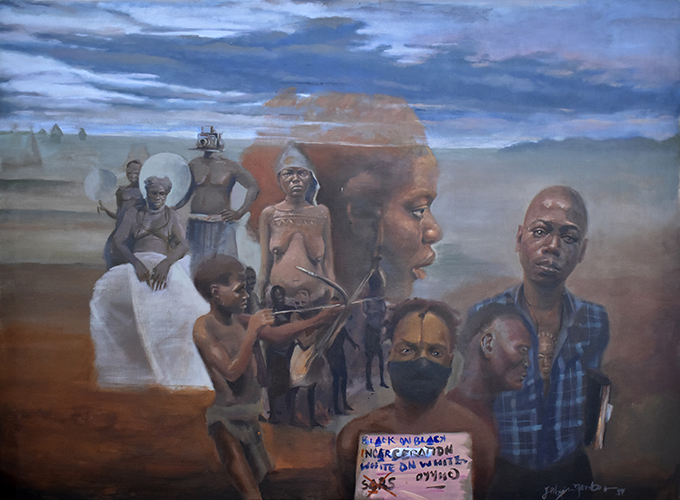

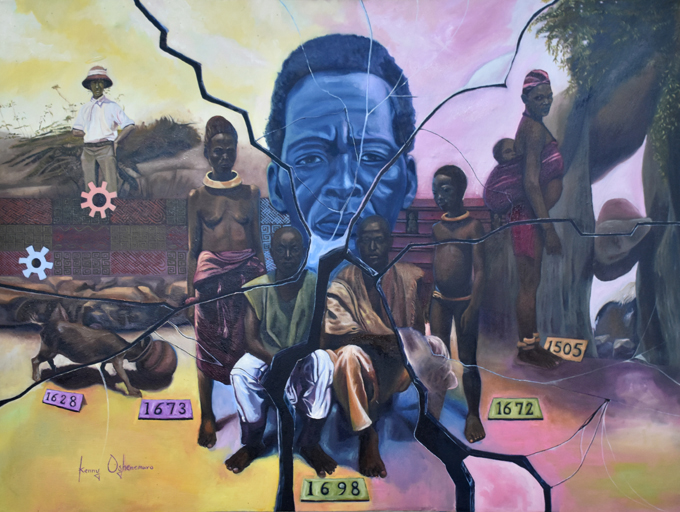

Chukwunonso Uzoagba in a Lecturer in the Department of Fine and Applied Arts at Nsukka, specialising in graphics and art education. He has a particular research interest in Igbo rites of passage and ritual practice – aspects of traditional life that were thoroughly documented by Northcote Thomas.

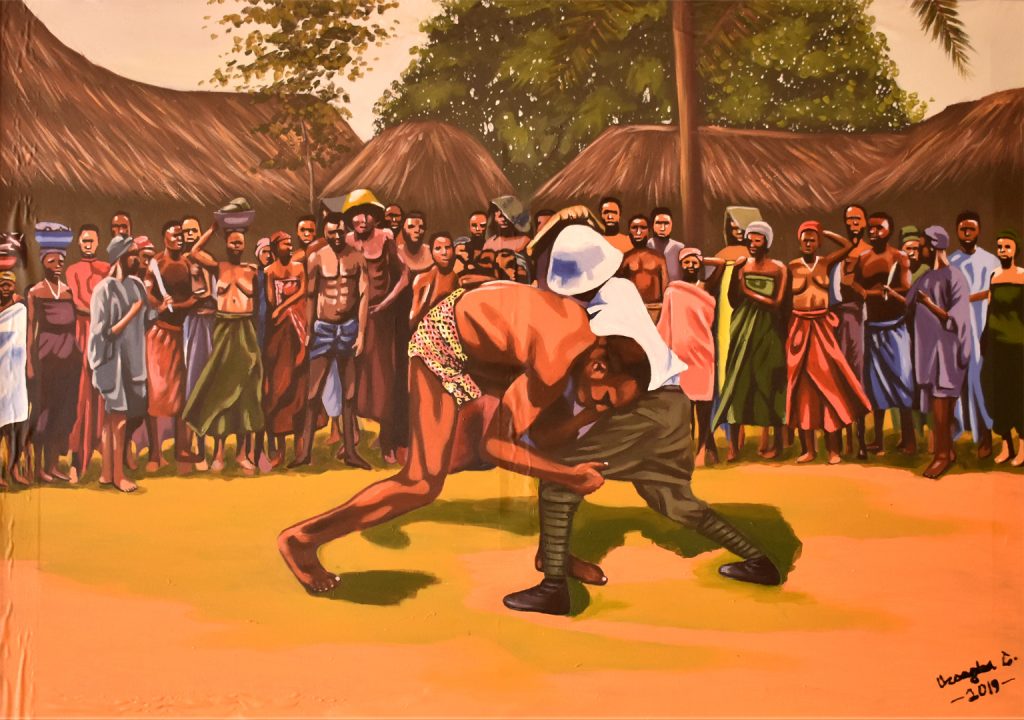

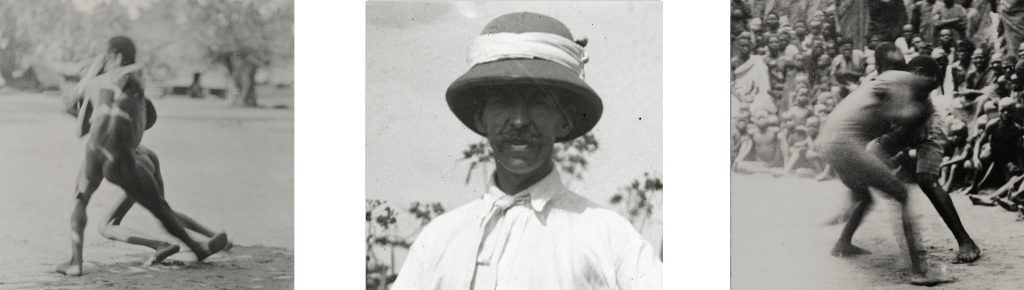

When Uzoagba encountered the Northcote Thomas archives as part of the [Re:]Entanglements workshop at Nsukka, he was immediately drawn to Thomas’s photographs of wrestling matches. Wrestling was very much a traditional art form and part of festivals marking coming of age ceremonies. Combining various elements from different photographs, including a portrait of Thomas himself, Uzoagba wanted to use the wrestling match as a metaphor for the struggle of Igbo people with the forces of colonialism. The title ‘Ogo Mnwere Onwe’ translates into English as the ‘Struggle for Freedom’.

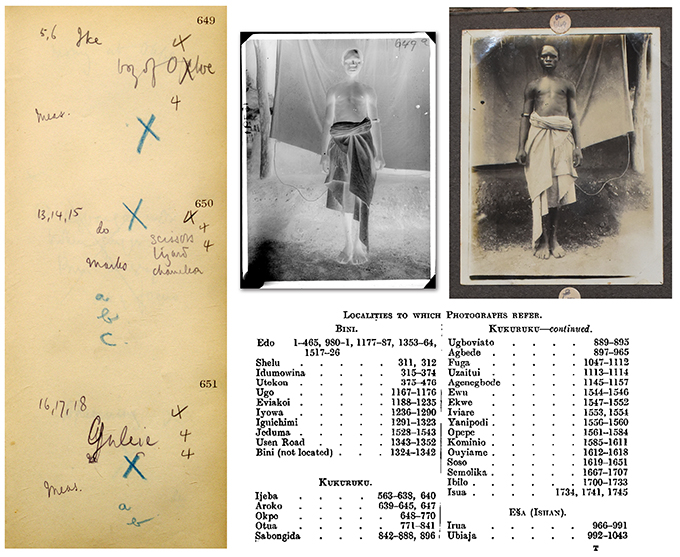

Chukwuemeka Nwigwe, Nibo Lady Fashionista, The Last Sacrifice, Eze Nri

Chukwuemeka Nwigwe teaches art history, textiles and fashion at Nsukka. He has a particular interest in the history of Igbo dress and had already drawn upon the work of Northcote Thomas and other colonial-era publications in his PhD research. While Nwigwe made use of the small selection of photographs published in Thomas’s Anthropological Report of the Igbo-speaking Peoples of Nigeria, through the [Re:]Entanglements project he was able to access a vast archive of thousands of images relevant to his research. He was able to utilise these in a recent postdoctoral fellowship.

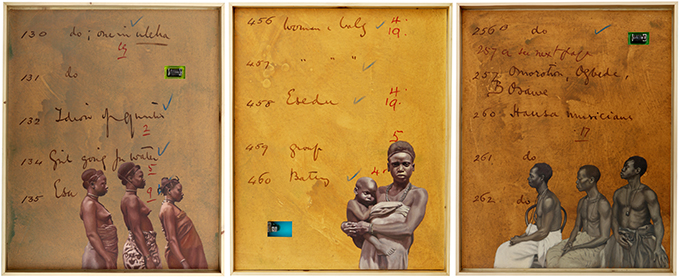

For the ‘[Re:]Entangled Traditions’ exhibition, Nwigwe produced three mixed media works, experimenting with weaving techniques inspired by the nest-building techniques of the village weaverbird to create silhouetted figures of characters from the Thomas archive. He used silhouettes to reflect the mystery surrounding these characters, which can only be seen imperfectly in Thomas’s monochrome images.

The backgrounds of each panel are made from discarded poly materials – especially brightly-coloured polythene strips used to wrap motorbike tyres. Nwigwe explains how he collected these from roadside mechanics’ shops.

Jennifer Ogochukwu Okpoko, The Beauty Within

Jennifer Ogochukwu Okpoko graduated from the University of Nigeria, Nsukka in 2018 just before the collaboration with the [Re:]Entanglements project began. She specialises in textile design. As part of her undergraduate studies, she conducted research with traditional Igbo weavers in Delta State.

When Okpoko started exploring the Northcote Thomas archives after the initial [Re:]Entanglements collaboration workshop, she was excited to see photographs of uli murals from her hometown, Agulu, in Anambra State. She chose to feature one of these in her work for the exhibition.

Her piece, entitled The Beauty Within, comprises three large panels, each reproducing the uli mural using different textile materials and techniques. The first uses tapestry weaving using a limited palette of earth colours, similar to the colours that are likely to have been used in the original wall paintings. The second panel has a tiled form, in which vibrant colours are used in the tapestry woven squares, juxtaposed with the earth colours in the other sections. The third panel is mixed media using tapestry weaving and embroidery techniques to recreate the mural in bright contemporary colours.

Ugonna Umeike, Renewal

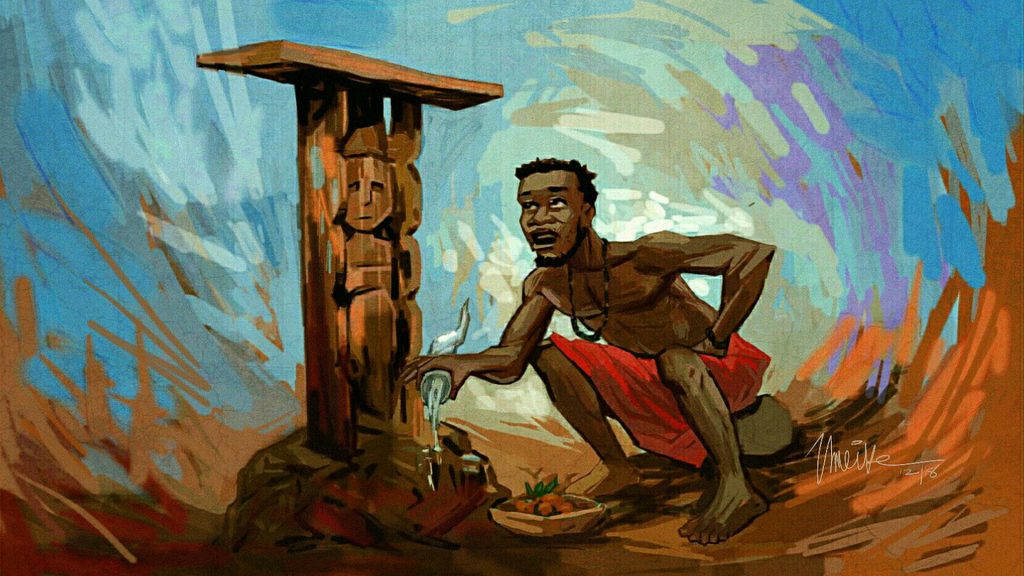

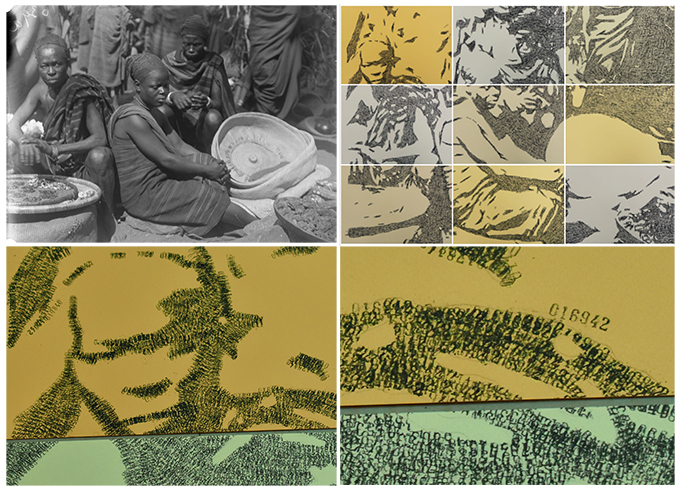

Ugonna Umeike majored in sculpture at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, but he has a wide range of interests including illustration, painting and digital art. Umeike was particularly interested in Northcote Thomas’s artefact collections and field photographs of traditional material culture. These he brought to life in a series of digital illustrations that were exhibited in the ‘[Re:]Entangled Traditions’ show.

Umeike also exhibited an illustration of one of the stories that Northcote Thomas recorded and transcribed – ‘The Blind Man, the Cripple, the Poor Man, the Thief and the King’ – which will be the subject of a separate blog post. Finally. he is working on a comic strip of another story recorded by Thomas.

Livinus Kenechi Ngwu, Mask with ichi

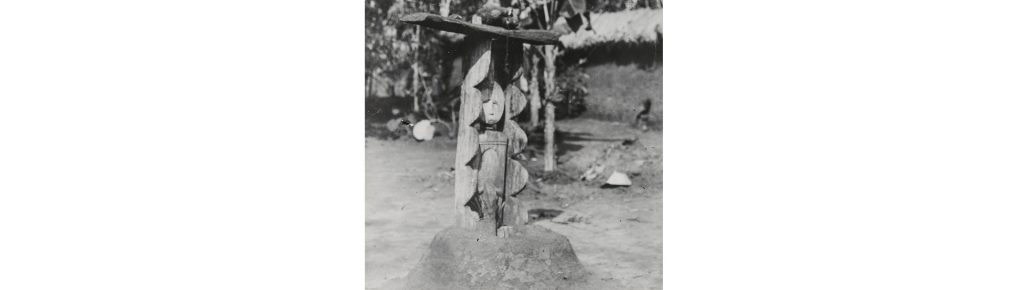

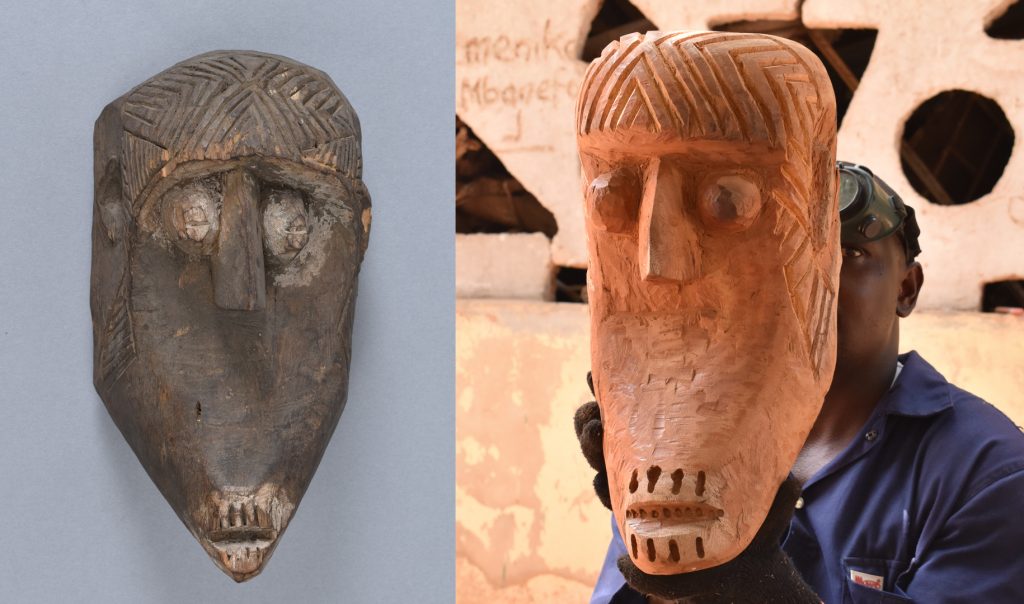

Livinus Kenechi Ngwu is a Lecturer in Sculpture at Nsukka. He works in various materials. For the ‘[Re:]Entangled Traditions’ exhibition Ngwu carved a wooden mask using traditional tools and techniques inspired by one of the masks collected by Northcote Thomas in 1911.

The original mask, which was collected in Ugwoba in present-day Anambra State, is described by Thomas as ‘isi maun apipi’. On its forehead are representations of the ichi scarification marks.

‘[Re:]Entangled Traditions: Nsukka Experiments with an Anthropological Archive’ was curated by George Agbo and Paul Basu. We would like to thank all the artists who participated in the collaboration. Especial thanks to Chijioke Onuora and Krydz Ikwuemesi for championing the project within the Department of Fine and Applied Arts; to Chika Kanu for designing the exhibition catalogue; to Glory Onwuasoanya Kanu for coordinating catering at the exhibition launch; to HRM Obi Martha Dunkwu for travelling from Okpanam to open the exhibition; to Emmanuel Ifoegbuike for his invaluable assistance; and to Charles Igwe, Vice Chancellor of the University of Nigeria, Nsukka for supporting the initiative.

See also the following posts on other contributors to the exhibition:

- Samson Uchenna Eze

- Ikenna Onwuegbuna

- Gloria Okeke and Ogechukwu Miracle Uzoagba (coming soon!)

![Scenes from opening of [Re:]Entanglements exhibition, National Museum, Lagos](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/National_Museum_Lagos_exhibition_opening_re-entanglements.net_.jpg)

![[Re:]Entanglements exhibition view, National Museum, Lagos](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/National_Museum_Lagos_exhibition_view_re-entanglements.net_.jpg)

![[Re:]Entanglements exhibition view, National Museum, Lagos](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/National_Museum_Lagos_exhibition_view_2_re-entanglements.net_.jpg)

![Kelani Abass [Re:]Entanglements Contemporary Art & Colonial Archives Exhibition, National Museum Lagos](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Kelani_Abass_exhibition_National_Museum_Lagos_re-entanglements.net_.jpg)