Uli is a celebrated traditional Igbo artform. It has been the subject of many studies, and has inspired subsequent generations of Nigerian artists, particularly those associated with the famous ‘Nsukka School‘. The word uli refers to a number of plants in Igboland, the berries of which are processed to produce a dark dye that was traditionally used to draw tattoo-like designs on the skin. Many of the design motifs of this body art were also used in murals often painted onto the mud/clay walls of shrines. These murals were usually created with a limited palette of locally available earth pigments – white (nzu), yellow (edo), red (ufie) and black (oji). Both body and mural designs are also known as uli, and both were ephemeral – that painted on the body might last a week or two before fading, while wall paintings would typically be renewed annually after the rainy season or in the days before a festival. Traditionally, uli was an artform practiced by women. The mural painting especially was a communal art.

In terms of composition, uli is characterised by linear forms, stylised motifs drawn from nature, elongated figures, outline shapes filled with dots or cross-hatching, and the use of ‘negative space’. There is generally a great economy of form; the skilled uli artist is able to evoke the world around them in their work by ‘depicting only the essential lines that make up any given object’ (Adams 2002: 246).

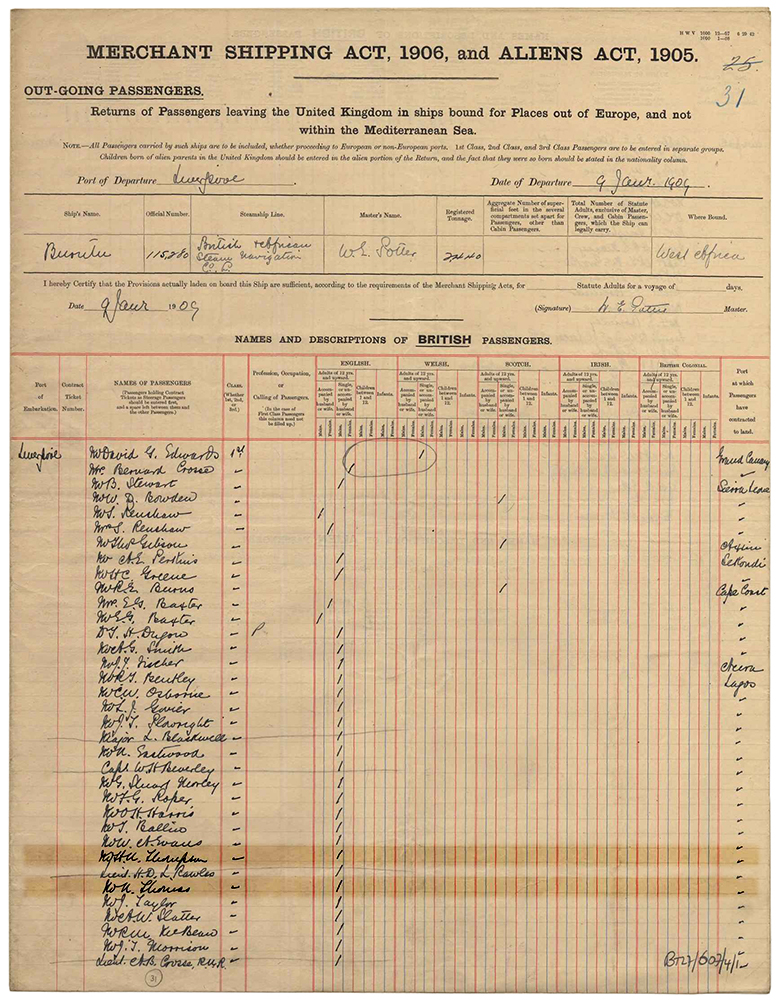

To the best of our knowledge, Northcote Thomas was the first to document uli photographically during his anthropological surveys in Southern Nigeria. Despite this, scholars of uli have neglected this important photographic archive and have tended to focus on the later documentation of colonial administrator-anthropologists such as M. D. W. Jeffreys and G. I. Jones in the 1930s and 1940s. Thomas’s documentation of uli dates to his 1910-11 tour in what was then known as Awka District, corresponding approximately to present-day Anambra State.

Only now, in the context of the [Re:]Entanglements project, have the photographs from Thomas’s surveys been comprehensively researched. There are over 100 images relating to uli in the archive, but, as with many topics that Thomas investigated, his findings were not written up or published. Only one photograph of an uli mural was, for example, published in Thomas’s Anthropological Report on the Ibo-speaking Peoples of Nigeria in 1913, accompanying his brief description of the shrine complexes of local deities (alusi) in Igbo traditional religion. He mentions in passing that ‘worship’ would take place ‘in an area of ground, frequently of considerable size, specially set apart for the purpose’ and that these sacred spaces would often be ‘surrounded by a wall decorated with curious paintings’ (Thomas 1913: 28).

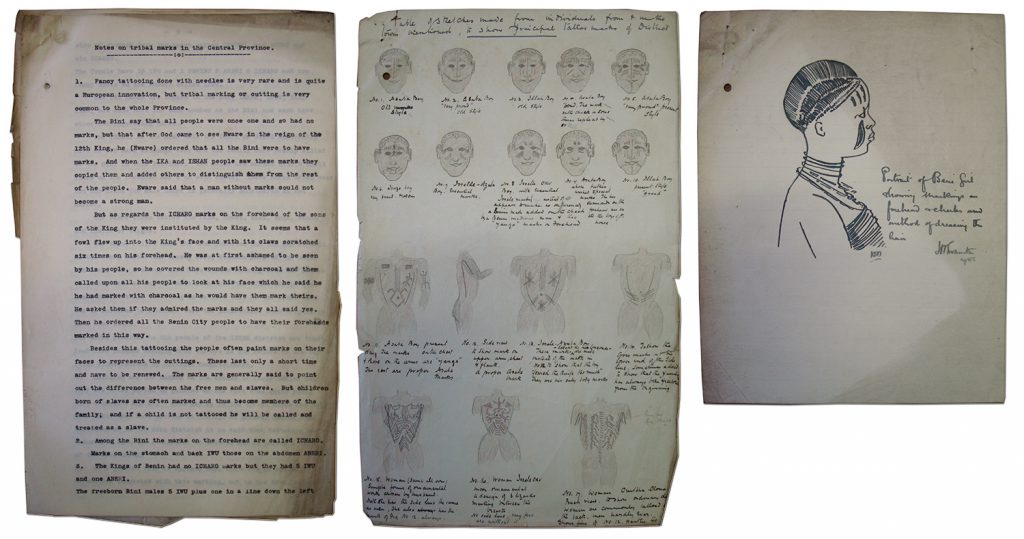

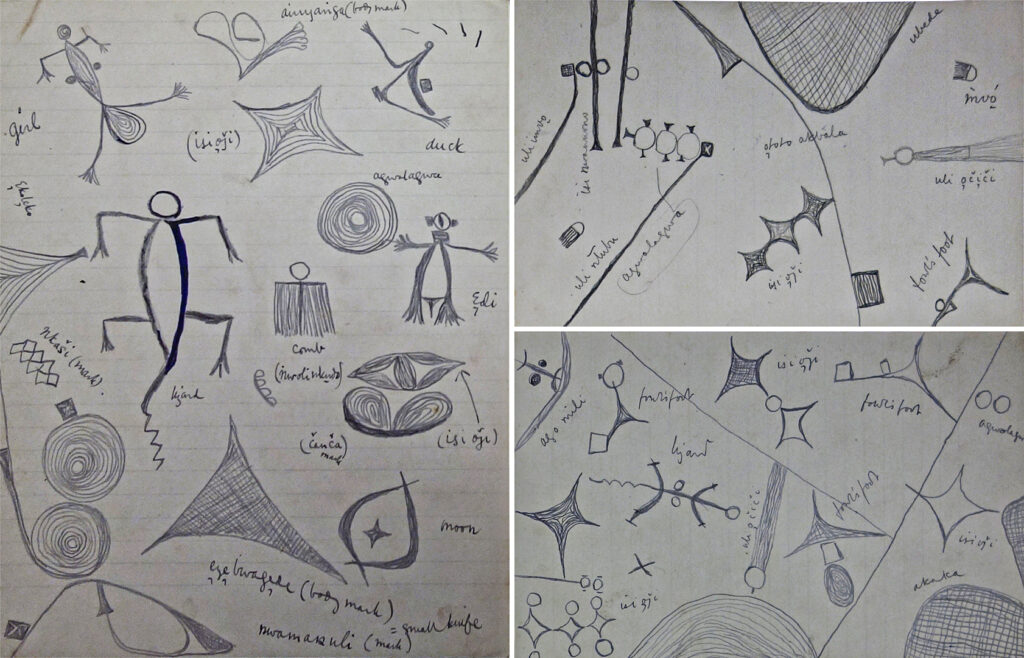

From such a limited account of these ‘curious paintings’, one might conclude that Thomas had no interest in art or aesthetics as subjects of anthropological inquiry. It must be remembered, however, that Thomas had been cautioned by the colonial authorities that he should focus on matters of a ‘practical nature’, relevant to colonial administration, and not get distracted by topics of primarily academic interest. The fact that Thomas took so many photographs of uli wall designs suggests that he had more than a passing interest in local artforms (several pages of the official photograph albums from his tours were devoted to this theme). Unfortunately few of Thomas’s fieldnotes survive from his Igbo surveys. What has survived, however, is an intriguing collection of annotated drawings of uli motifs, suggesting that Thomas did make enquiries about them. While he does not appear to have written up this aspect of his research, Thomas did publish an article following his 1909-10 tour in the anthropological journal Man concerned with ‘Decorative Art Among the Edo-Speaking Peoples of Nigeria‘ (Thomas 1910). This was largely focused on mural designs.

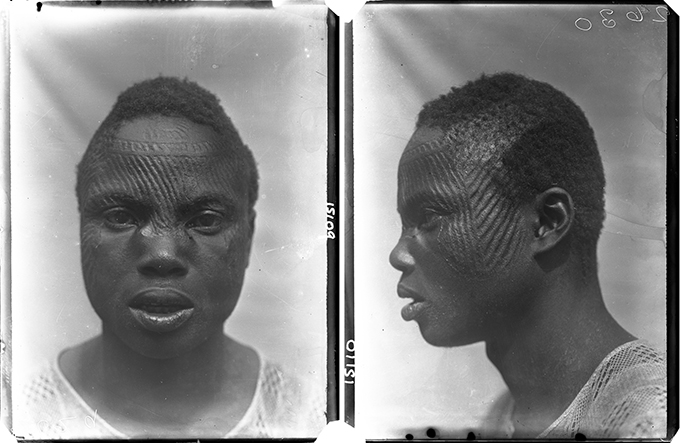

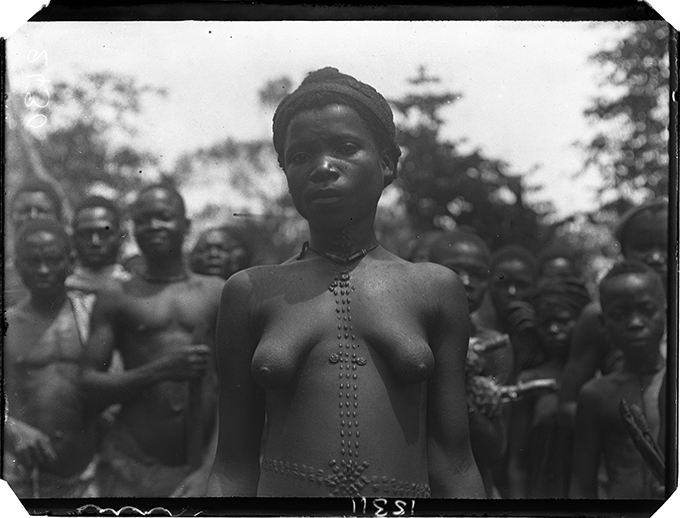

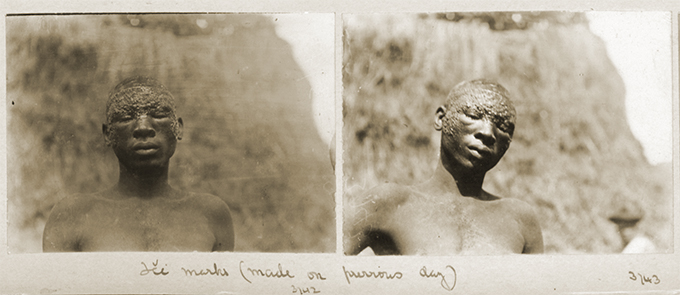

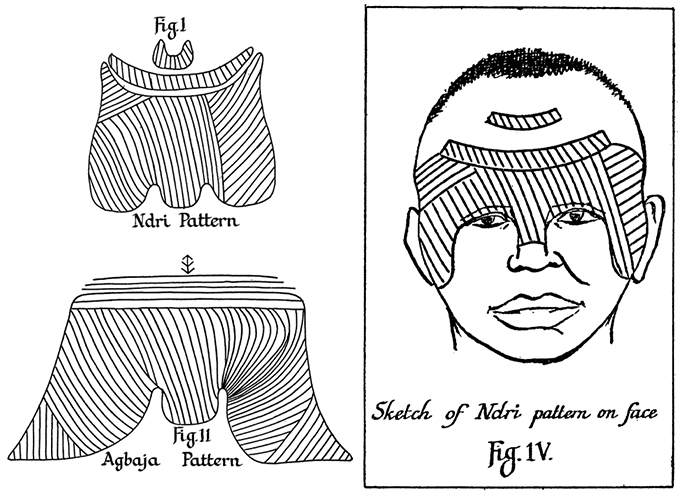

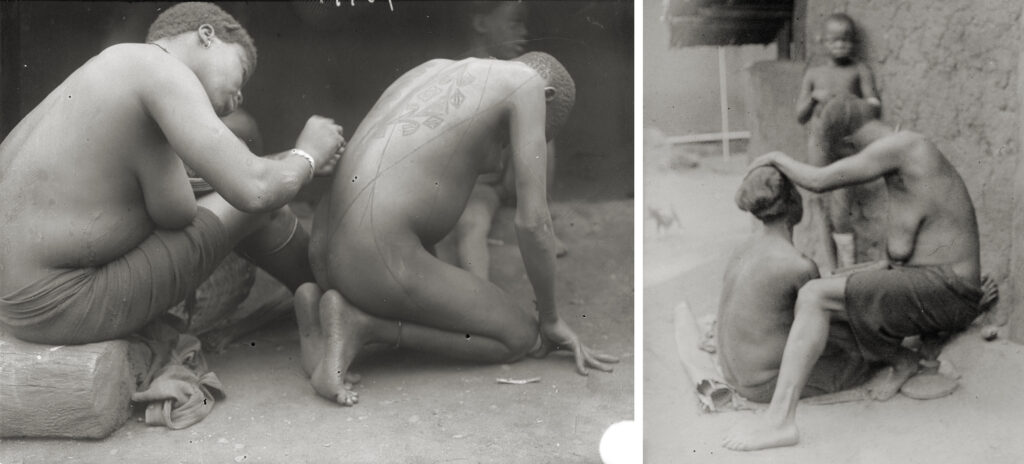

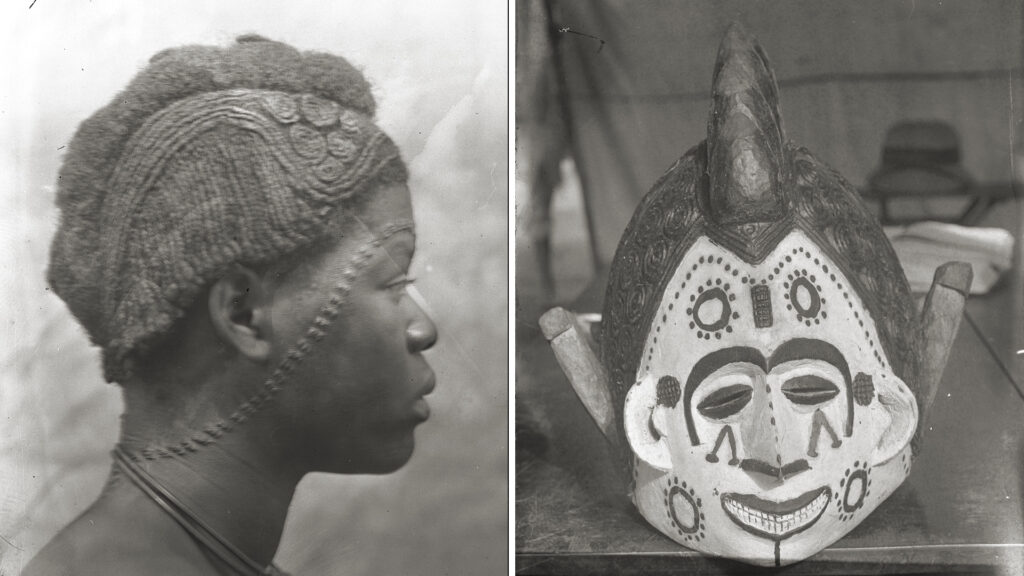

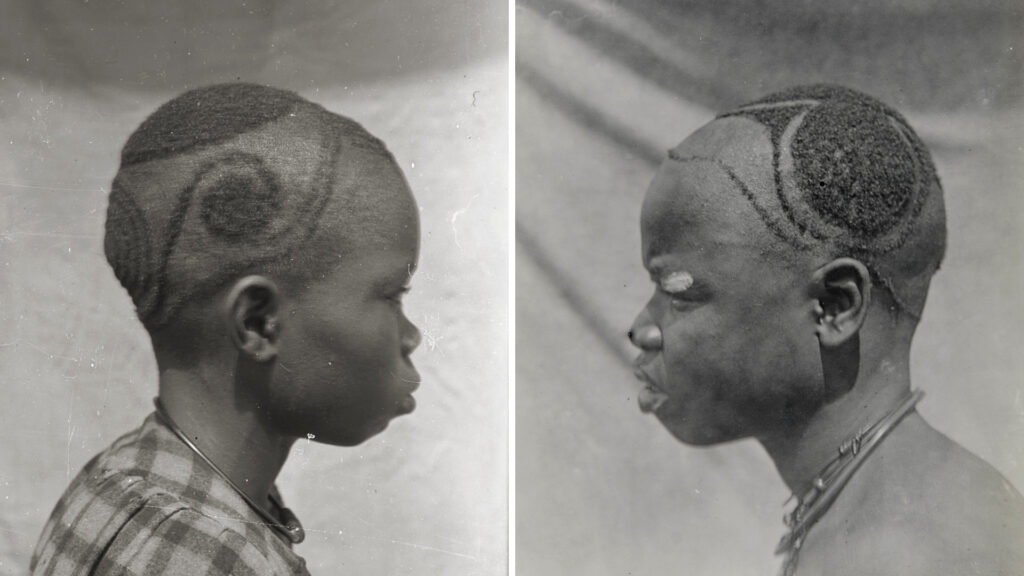

Between November 1910 and December 1911, Thomas and his local assistants conducted field research in approximately 18 different towns in Awka District. He made photographs of what we would readily identify as uli wall paintings in the towns of Agulu, Agukwu Nri, Nibo, Nise and Amansea. There are also photographs of other, less characteristic wall paintings and designs – some including typical uli motifs – either incised or moulded in relief in the fabric of the walls. Notable examples of the latter were made in Awka, Agulu, Agukwu Nri, Enugu Ukwu, Nimo and Amansea. While uli is generally regarded as a traditional Igbo art, this is really a stylistic determination. Thomas documented the same methods for creating both body and mural art during his Edo tour. In the context of body marking, for example, the equivalent of uli is known as asu in Edo. (Like uli, this is also the name of the plant from which the dye is produced.) What is especially evident in Thomas’s documentation of such practices in his Awka District tour, however, is the need to understand uli designs within a wider Igbo aesthetic manifested in a wide range of media, including other body arts such as scarification and hairdressing, as well as wood-carving, metalwork, and textiles.

Thomas may also have been the first to attempt to compile a glossary of uli motifs, with their Igbo names and interpretations. Among his unpublished fieldnotes are many loose-leaf pages of drawings, apparently drawn by different informants, with annotations in Thomas’s hand. Subsequent researchers have compiled more systematic glossaries of uli motifs, notably Elizabeth Willis’s 1987 ‘Lexicon of Igbo Uli Motifs‘ published in the Nsukka Journal of the Humanities. As Chuu Krydz Ikwuemesi notes, however, Willis’s ‘compendium is neither an uli bible nor a complete dictionary of uli. Motifs can vary from region to region and artists are always free to invent new ones. Uli is not a codified sign language; rather it is an ideogram in its own right, one which tends to capture through its abstract and minimalist tendencies the worldview and philosophy of the Igbo’ (Ikwuemesi 2019: 175). Nevertheless, it is interesting to understand that what may appear as abstract designs are often in fact representational forms.

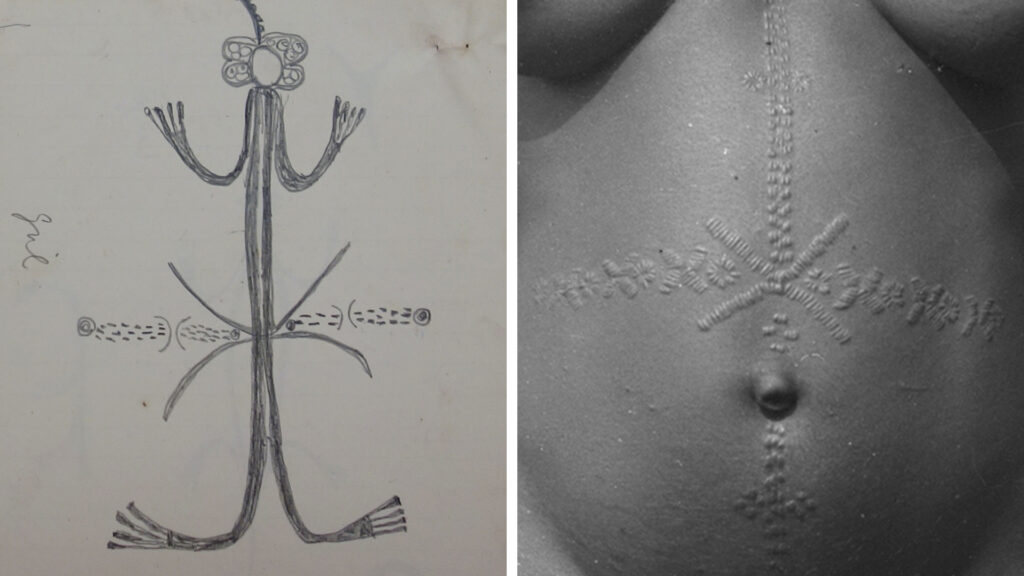

Setting these drawn motifs alongside corresponding photographs in the archive enables one to compare representational form across different media. One can, for instance, compare the representation of mbubu scarification marks, an adornment made on young women’s abdomens prior to marriage, in a drawing of an uli figure with the actual scarification marks. It is interesting to note how the belt-like strip of alternating crosses and circles, which wrap around the woman’s waist, extend out from the drawing of the body as a horizontal band.

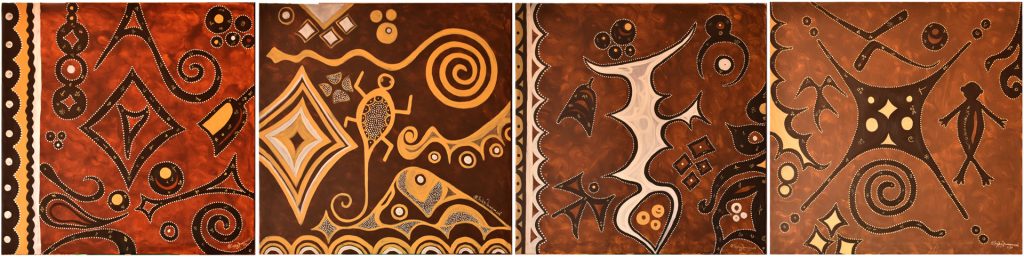

As part of the [Re:]Entanglements project, we have re-engaged with the anthropological archive in different ways. We have, for example, taken the photographs back to the communities at the locations in which they were originally taken. As well as ‘repatriating’ this cultural heritage to the communities, this has allowed us to learn more about the sites photographed and, occasionally, the murals themselves. Recognizing that these photographs also represent an important visual archive of traditional aesthetic forms, we have also shared them with contemporary artists and invited their creative responses. There is a long tradition of creative re-engagement with traditional Igbo arts at the Department of Fine and Applied Arts at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, and a number of participating artists chose to respond to this newly accessible repository of historical uli murals. The results of the collaboration with Nsukka-based artists were displayed at the [Re:]Entangled Traditions exhibition at the University of Nigeria in February 2020, and a selection of the works were also included in the [Re:]Entanglements exhibition at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology in Cambridge (June 2021 to April 2022).

When documenting uli wall paintings, Thomas sometimes took just one or two photographs of a particular wall or building. In other case, he took multiple photographs, even using different types of camera. He documented four locations in particular detail: the Ogwugwu shrine at Agulu, the Iyiazi shrine in Agukwu Nri, the Ngene (probably Ngendo) shrine in Nibo, and the Mpuniyi shrine in Nise. During fieldwork for the [Re:]Entanglements project, we visited these locations, left copies of the photographs with community members, and collected accounts of each of the sites.

Agulu: Ogwugwu shrine and ‘Ochiche’s house’

During his anthropological survey of Awka District, Thomas made a number of visits to the town of Agulu. In February 1911, he documented what he called the ‘Ogugu ceremony’ and ‘Ogugu house’. Today, ‘Ogugu’ is spelled ‘Ogwugwu’. Ogwugwu is a female deity or alusi. An annual festival was held for Ogwugwu, and it is likely that the walls of the Ogwugwu shrine were painted in preparation for this. As can be seen from Thomas’s photographs, the paintings appear fresh and unweathered.

When we visited Agulu, we were told that Ogwugwu was a very popular deity of the region and that Ogwugwu shrines were to be found in every settlement. One would make sacrifices at the shrine, appealing to the alusi to grant one children and wealth. In Agulu, the two major deities were Haaba and Ududonka. Ogwugwu is regarded as the child of Ududonka. There is still a shrine in Agulu known as Ududonka Ogwugwu, and it was felt that this is the place that Thomas photographed.

It appears that Thomas photographed two different structures decorated with uli wall paintings. The above detail is taken from one of a series of photographs documenting the Ogwugwu ‘ceremony’. The series shows a group of men dancing in front of a structure – possibly a thatch-topped wall enclosing the sacred precinct – to the accompaniment of ufie drums. The wall is divided into a series of painted panels, each with a distinct repeating design. The second structure, which Thomas labels Ogwugwu ‘house’ seems to be one of two shrine buildings within the enclosure (he also photographed a ‘small house’, but this is not painted with uli designs).

The uli designs on the shrine building are quite different from those on what we are interpreting as the enclosure wall. They include a number of more representational forms, including a python (eke), a venerated totemic animal in Agulu, and a human figure (perhaps wearing a masquerade headdress or carrying a pot on the head). The composition includes other familiar uli motifs, including lozenge shapes with alternating light and dark colours. One of the photographed walls of the Ogwugwu ‘house’ is different again, with repeating patterns that resemble those of small body stamps used to print uli motifs on the body.

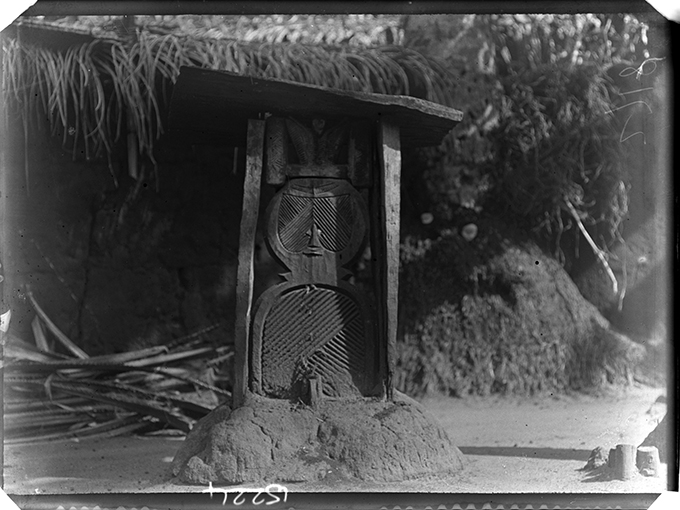

On a subsequent visit to Agulu, Thomas photographed a building he labelled ‘Ochiche’s house’. Rather than being painted, the designs on the walls are created in relief in clay. In addition to the relief designs of a python, lizards, an ogene gong and a fan (all familiar uli motifs), there is also a series of three-dimensional carved clay figures extending out from the wall. The latter appears to include two male figures, a mother and child, and a female alusi figure (the form of which closely resembles the carved wooden alusi figure collected by Thomas in Awgbu). A further figure can be made out on the side wall on the right of the photograph. Although Thomas refers to the building as ‘Ochiche’s house’, this is likely to be a shrine rather than a residence. (Thomas also referred to the Ogwugwu shrine as the Ogwugwu ‘house’.) Thomas also photographed other locations such as the ‘Obu of Ochiche’ and the ‘Sacrificing place of Ochiche’, suggesting the shrine was located in the compound of a prominent individual named Ochiche. During our fieldwork in Agulu, however, this name was not recognised.

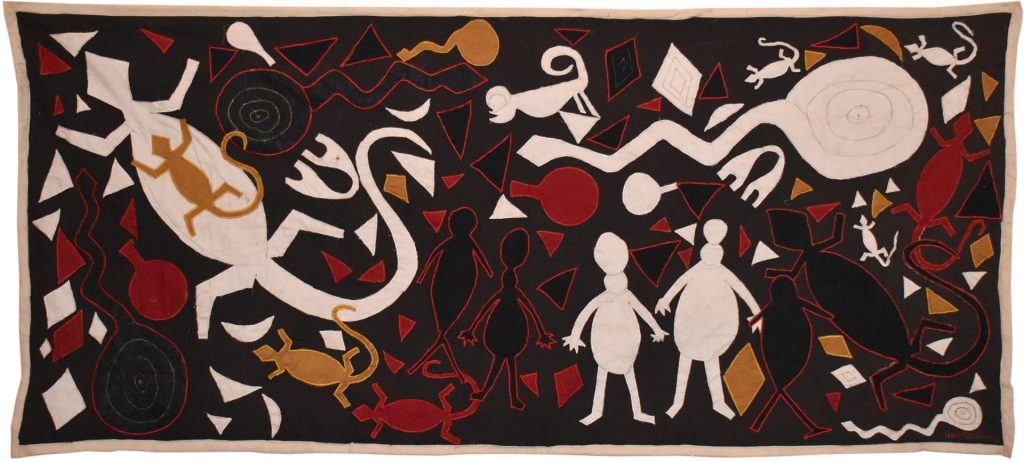

As part of the [Re:]Entangled Traditions collaboration with Nsukka-based artists, the uli motifs from both the Ogwugwu shrine and ‘Ochiche’s house’ provided inspiration for the textile artist RitaDoris Edumchieke Ubah, whose late aunt was herself an uli artist. Ubah combines various motifs from Agulu in her applique work entitled Igbo Kwenu. Over 3 metres in length, this remarkable uli tapestry was one of the works selected for display in the [Re:]Entanglements exhibition in Cambridge.

Agukwu Nri: Iyiazi shrine

Thomas spent a considerable amount of time in Agukwu Nri during his 1910-11 anthropological survey. In May 1911, he photographed the remarkable uli designs on what he described as the ‘market house’. During our fieldwork in Agukwu Nri, this was identified as the Iyiazi shrine, which was located in the Afo market place in Amaeze, in the Agbadana section of Agukwu Nri. Iyiazi is the main alusi of Amaeze. Traditionally the women of Amaeze would decorate the shrine in the lead up to the annual Ife Iyiazi festival.

The uli paintings of the Iyiazi shrine in Agukwu Nri are perhaps the most documented in Igboland. Most of this documentation has, however, taken place in the last 50 years and records various attempts to revive the uli art tradition. To the best of our knowledge, Thomas’s photographs taken in 1911 are the only record of the paintings from a time when the Iyiazi cult and its festival were still active. According to Elizabeth Willis, the first time that the shrine was painted after the Biafran War was in 1972 in connection with the opening of the Odinani Museum. The Odinani Museum was established by the Ibadan-based anthropologist Michael Angulu Onwuejeogwu adjacent to the Afo market and therefore close to the shrine. A student at University of Nigeria, Nsukka, H. T. Agbogu, photographed the designs that the Amaeze women painted in 1972 and again in 1973 for his BA dissertation (Agbogu 1974).

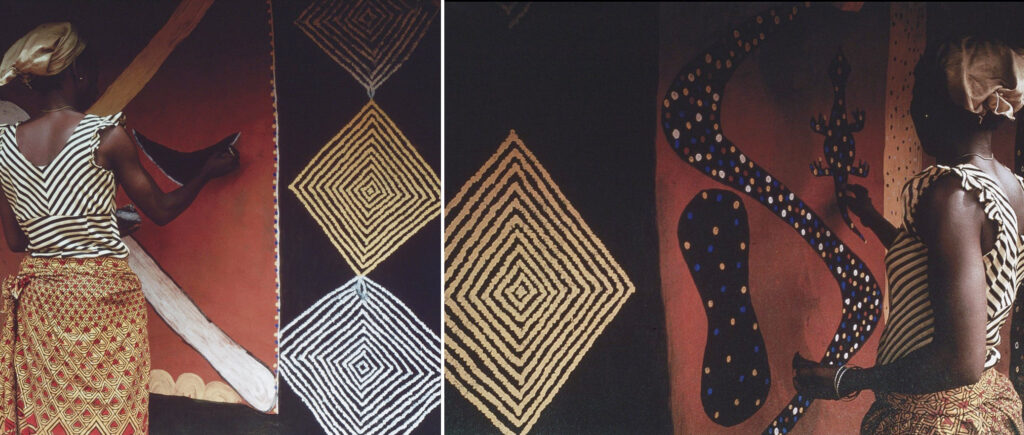

Unfortunately the shrine again fell into disrepair. Then, in 1984, the Nsukka-based artists Obiora Udechukwu and Chike Aniakor, along with the American art historian Herbert Cole, led a project to restore the shrine walls and commission the women artists of Amaeze to repaint it. Udechukwu photographed the dilapidated state of the shrine prior to the renovation and reported with regret that: ‘It captures graphically not just the decline of physical structures but the decline of a whole system of beliefs, practices, social and economic relations, art, and culture in general’ (cited in Willis 1998: 165). Some 50 women were enlisted to paint new murals as part of the project. The process and finished paintings were documented thoroughly and have been published in various books and articles on uli (e.g. Cole and Aniakor 1984).

The cycle of decline and revival has occurred again and again. In 2003-4, Udechukwu returned to Nri, this time with his younger Nsukka colleague Chuu Krydz Ikwuemesi, to lead another restoration and repainting project. In his essay about the project in Uli and the Politics of Culture (Ikwuemesi 2005), Krydz Ikwuemesi notes that it was very difficult reassembling the women artists who had worked with Udechukwu twenty years earlier. Many were now very elderly or had died, others declined the invitation to participate, explaining that they had converted to Christianity. Udechukwu and Ikwuemesi eventually found 12 women, most of whom were from other towns but had married into Nri families, to work on the project. Ikwuemesi explains that they brought their own uli traditions to the work.

We made several trips to Agukwu Nri as part of the [Re:]Entanglements project. The Iyiazi shrine was undergoing a further transformation at this time. The walls at the original shrine site were no longer standing, though the sacred trees of the shrine still stood in the old market place (now flanked by modern buildings). The Odinani Museum itself had long fallen into disrepair and was in the process of being restored by the local philanthropist Chief Charles Tabansi. As part of the restoration, the location of the shrine was moved to a site immediately adjacent to the museum and new concrete walls were erected around it. For the reopening of the Museum on 28 December 2018, the walls of the new Iyiazi shrine were painted with uli motifs by a group of art students from Nnamdi Azikiwe University, Awka, under the direction of Tony Otikpa, a retired art lecturer resident in Nri.

Nibo: Ngene shrine

The most detailed photographic documentation of an uli-painted structure made by Northcote Thomas was of the ‘Ngene house’ in Nibo. Thomas visited Nibo in June 1911. Ngene is a male alusi (spirit/deity). In nearby Enugu Ukwu, Ngene’s female consort is Ogwugwu, whose shrine Thomas photographed in Agulu. There are many Ngene shrines in Nibo, including Ngene Okweafa, Ngene Ezeonyia, Ngene Ukwu and Ngene Igweagu. During fieldwork in Nibo, the shrine that Thomas photographed in 1911 was identified as that called Ngene Ngendo. This is the shrine of the Ngene whose mother is the deity Udo, whose own shrine is close by and was also photographed by Thomas. The name ‘Ngendo’ is a compound of ‘Ngene’ and ‘Udo’.

During our fieldwork, [Re:]Entanglements project researcher George Agbo discussed Thomas’s photographs with two elders, Nwoye Okoya Ogbuefi and Evelyn Echeta. Evelyn Echeta had herself participated in the painting of the Ngendo shrine wall in 1953-4. They explained that the wall decoration would be done by younger women and girls in the days leading up to the ikpo ngene, the festival of the Ngene alusi. Those participating were from families who were adherents of Ngene.

The painting of the wall was a festive occasion in itself. The young women would bring food with them. We were told that of the approximately 40 participants, only about five would actually create the uli artworks. The majority of the women would support them by fetching water, preparing the colours and so on. The decorative motifs were a matter of personal choice of the artists. The designs were inspired by plants, animals and personal objects as well as including abstract forms.

The designs were painted using a stick that had been crushed at one end to create an improvised fibre brush. The coloured paints were made from pigments sourced from the local environment: nchala, a yellow clay deposit sourced from a local stream; nzu, crushed white kaolin chalk; ufie, a dark red pigment from ground camwood; and anunu, a type of leaf that is mixed with unyi (charcoal). Each of these would be mixed with water to create the yellow, white, red and black colours used in the paintings.

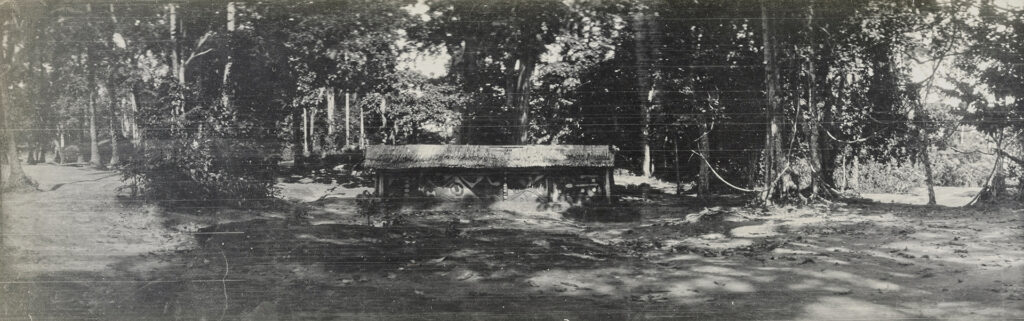

The mud wall itself was used to separate the sacred space of the shrine (the ebede alusi) from the wider arena, which the public are permitted to access. The wall is topped with a thatch (aju) to protect it from being weathered away by the rain. It is difficult to ascertain the layout of the walls from Thomas’s photographs – in one image there is a gate way, through which one can see a second wall, which is also painted with uli motifs. It is not clear if this is a separate structure or the back wall of the walled enclosure.

Thomas photographed many sections of the wall. Some of the sections are contiguous and it has been possible to ‘stitch’ them together in Photoshop to get a better sense of the overall design. The design includes many ‘classic’ uli motifs, including odu (elephant tusk), eke (python) and nnyo (mirror).

As part of our fieldwork, George Agbo and Glory Chika-Kanu attended the Iwa Ji Ngendo (Ngene New Yam Festival) in Nibo in September 2019. We were invited to set up a ‘pop-up’ exhibition of Thomas’s photographs taken in Nibo, including those of the Ngene shrine walls, which attracted much interest. During the festival the area around the Ngendo shrine was filled with people bringing offerings for Ngene and seeking the intercession of the Ngene priests to pray for them to the deity. Although the beautifully-painted walls that Thomas photographed in 1911 are now little more than eroded banks of earth, they still mark the boundary between sacred and profane space.

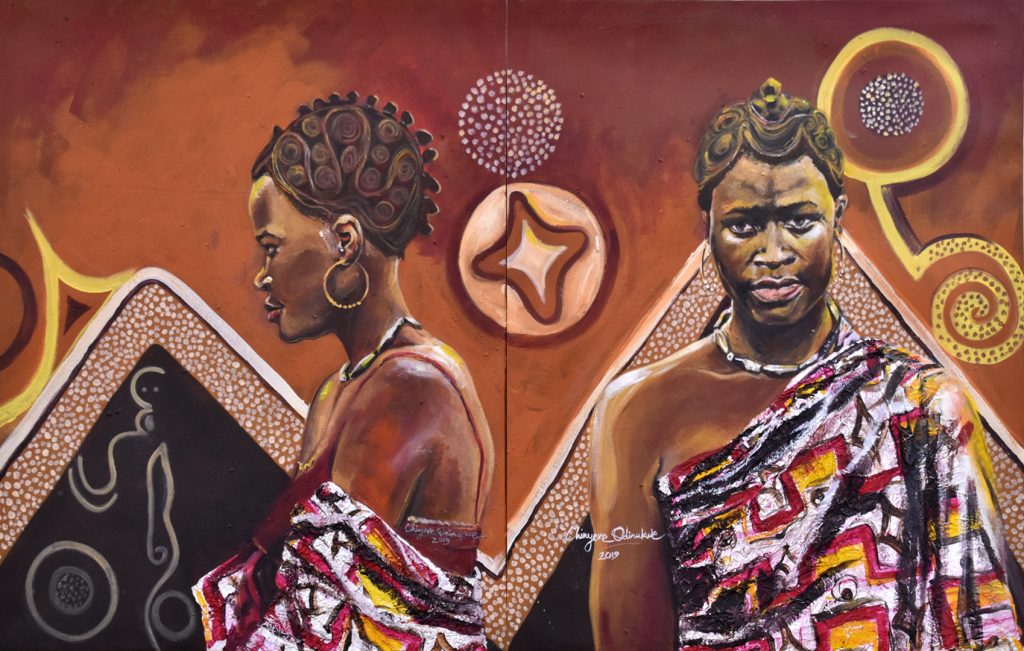

Thomas also photographed another uli-covered building in Nibo, which he labelled ‘Odelegu’ (see photograph at the top of this article). This includes beautiful representations of human forms. For the [Re:]Entangled Traditions exhibition, artist Chinyere Odinukwe reworked these Odelegu murals, using them as a backdrop for her portrait of a woman named Nwambeke who Thomas also photographed in Nibo in 1911. Although Odinukwe grew up in the Abuja, she recalls seeing such uli designs on visits to Nibo, her maternal home town, as a child. Her painting draws attention to the links between uli and traditional hair design in Igbo culture.

Nise: Mpuniyi shrine

Northcote Thomas visited the town of Nise in August 1911. Here he photographed the decorated walls of the Mpuniyi shrine in a section of the town called Ara. One of the interesting aspects of the uli decoration technique at this shrine is the combination of painting and relief work. As with the other sites discussed in this article, Thomas did not publish any details of the shrine in his reports and no fieldnotes survive. During fieldwork in Nise, however, we met Felix Nweke Echele, who is the son of the last chief priest of Mpuniyi, and together with the stories of other elders, we were able to learn much about the shrine. When we were first shown the area we were told: ‘This is Mpuniyi, but the shrine is no more’. While the shrine is gone, the area remains an important sacralised space.

The Mpuniyi shrine took its name from the wider area in which it is situated, all of which is regarded as sacred. Behind the shrine the land falls away into a deep gulley along which runs the Olulu Mpuniyi stream. Water issues from the rocky sides of the gulley from a number of springs. The water from the stream is regarded as having healing power. Traditionally water was collected from the stream by a man especially designated for the task and brought to the shrine, where it was used for washing, cooking and other ritual purposes. While fetching the water to the shrine, this man had to be naked and had to hold a palm leaf (omu nkwu) between his lips. He was not permitted to talk with anyone, and could not put the water container down on the bare earth.

Felix’s father, Echele Edolu, died in 1966 when Felix was just 6 years old. The man who was to succeed as chief priest did not take up the position, however, due to his Christian faith and an alternative priest was not found. As a result the shrine went into decline and the building eventually collapsed. In the 1980s, a village hall and school were built in the vicinity, and in 2005 a large Catholic church dedicated to St Peter and St Paul was established on the site. By this time, the majority of the people of Ara were Christians. In the gulley an ‘adoration ground’ was established with various concrete statues inspired by biblical scenes. In 2012, the adoration ground and the Mpuniyi stream itself were blessed by the Catholic Bishop of the Awka Diocese in order to Christianise it. Just as people came from far and wide to seek the blessings of the Mpuniyi deity, crowds now come to the adoration ground to pray and take the holy water. It is a very interesting example of the sacred power of an indigenous deity and its shrine being appropriated by the Christian religion, and hence the Christianisation of the Igbo sacred landscape.

Amansea: decorated house

The majority of the uli decorated walls that Thomas photographed were associated with shrines devoted to particular deities. He did also document uli designs on the walls of the compounds of presumably wealthy families. A good example is the entrance gate to a compound of a family in Amansea. Unfortunately, Thomas did not record the name of the family.

The designs are made on the walls flanking two doorways, which would have had elaborately carved doors. The clay of the walls is incised with patterns and the paintings, of animal and human forms outlined in white or yellow dots, is created around these. In the foreground of the wider shot of the compound, a carved uwho (ancestral shrine) can be seen.

Uli, the Igbo heritage crisis and the colonial archive

In a recent article in the journal Utafiti, Krydz Ikwuemesi discusses the uli art tradition and its revival in relation to what he terms the Igbo ‘heritage crisis’. Ikwuemesi argues that one of the greatest misfortunes of modernisation in Igboland is the ‘dissonance that shapes the perception of tradition and heritage’ (2019: 187). This denigration of traditional Igbo culture is a legacy of colonialism and Christian missionary activity, but has also accelerated in the postcolonial era with the expansion of Pentecostalism and adoption of ‘Western’ values. This has led to an ‘intensive process of deculturation‘ in which ‘Igbo autochthonous ideas, including uli, are grossly devalued’ (2019: 188). ‘The triumph of Pentecostalism reflects the death of Igbo religion’, writes Ikwuemesi. And ‘the death of a people’s religion is invariably the death of their culture’ (ibid.).

While the social and political crises affecting so many Nigerians cannot be reduced only to the sphere of ‘culture’, the cultures of colonialism and Christianity have had a far-reaching impact. The question that Ikwuemesi raises is what role culture – including ‘cultural education’ – might play in shaping a better future, a future that is not based on ‘self-effacement’ and devaluation, but is rather grounded in indigenous values. What is needed, Ikwuemesi suggests is a ‘cultural rearmament’, in which art – including the art of uli – must be ‘chief among the arsenal’ (2019: 198).

Reflecting on the remarkable archive of traditional art represented in Northcote Thomas’s photographs of uli, one is struck by one of the cruel paradoxes of colonialism: that the same mindset that led to the destruction of the cultural worlds of the colonised also expended great effort in trying to preserve what it was destroying. The difference, of course, is that colonialism produced the anthropological archive, in which soon to be extinguished beliefs and practices were merely documented in photographs, drawings, sound recordings and artefact collections, whereas what was destroyed was a dynamic, living tradition. One of the questions that the [Re:]Entanglements project has been posing is whether, in the wake of colonialism, that anthropological archive has a role to play in what Ikwuemesi calls a ‘cultural rearmament’.

Many thanks to Dr George Agbo and Prof Krydz Ikwuemesi for their advice and assistance with this article.

References

- Adams, S. M. (2002) ‘Hand to Hand: Uli Body and Wall Painting and Artistic Identity in Southeastern Nigeria’. PhD dissertation, Yale University.

- Agbogu, H. T. (1974) ‘The Art of Nri: A Heritage of the Philosophy’, BA thesis, University of Nigeria, Nsukka.

- Cole, H. M. and C. C. Aniakor (1984) Igbo Arts: Community and Cosmos. Los Angeles: Museum of Cultural History, University of California.

- Ikwuemesi, C. K. (2005) ‘Primitives or Classicists? The Women Uli Painters of Nri’, in C. K. Ikwuemesi and E. Agbaiyi (eds), The Rediscovery of Tradition: Uli and the Politics of Culture, pp.1-34. Lagos: Pendulum Centre for Culture and Development.

- Ikwuemesi, C. K. (2019) ‘Problems and Prospects of Uli Art Idiom and the Igbo Heritage Crisis’, Utafiti 14.2, pp.171-201.

- Thomas, N. W. (1910) ‘Decorative Art Among the Edo-Speaking Peoples of Nigeria: I. Decoration of Buildings’, Man 10, pp.65-66.

- Thomas, N. W. (1913) Anthropological Report on the Ibo-speaking Peoples of Nigeria, Part I: Law and Custom. London: Harrison.

- Willis, E. A. (1987) ‘A Lexicon of Igbo Uli Motifs’, Nsukka Journal of the Humanities 1, pp.91-121.

![Lines, Faces, Fragments installation, [Re:]Entanglements Exhibition, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Re-Entanglements_exhibition_installation_Ozioma_Onuzulike_Lines_Faces_Fragments_2_re-entanglements.net_-683x1024.jpg)

![Lines, Faces, Fragments installation, [Re:]Entanglements Exhibition, Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Cambridge](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2021/07/Re-Entanglements_exhibition_installation_Ozioma_Onuzulike_Lines_Faces_Fragments_1_re-entanglements.net_-1024x683.jpg)