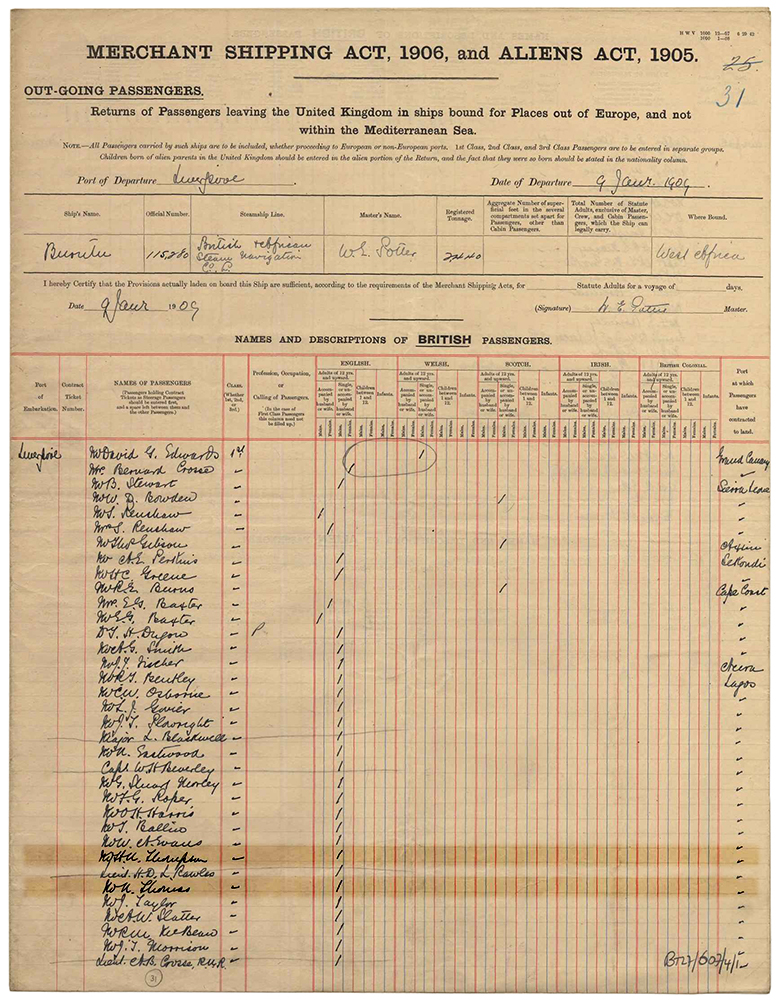

On this day, January 9th, in 1909, the Government Anthropologist, N. W. Thomas, set sail on the S. S. Burutu from Liverpool. Travelling on this Elder Dempster & Co. steam ship, he was bound for Lagos and his first experience of anthropological fieldwork in West Africa.

It was a more a matter of chance than design that N. W. Thomas’s became the first Government Anthropologist to be appointed by the British Colonial Office. A few years earlier, in 1905, the Chief Magistrate of the Gambia, A. D. Russell, had proposed distributing a questionnaire to colonial administrators in Britain’s West African territories in order to collect information about the ‘customary laws’ of local populations. It was thought that this information would be useful for those colonial officials who were responsible for ‘administering justice’ in the context of indirect rule. The proposal was adopted and over the following couple of years a large amount of material amassed at the Colonial Office.

At the same time, the academic discipline of anthropology was fast establishing itself in Britain. The first qualification in the subject was, for example, introduced at Oxford in 1906, and a first generation of professional anthropologists had been lobbying government for the establishment of an Imperial Bureau of Anthropology modelled on that already existing in the USA. In 1908, when the Colonial Office began considering publication of the information about customary laws in West Africa, it was decided that the job of editing the material should be entrusted to an anthropologist. On the recommendation of E. B. Tylor, N. W. Thomas was approached to take on this task.

Thomas’s review of the questionnaire material was, however, damning. He reported that the quality of the information gathered was extremely variable, and found fault both in the design of the questionnaire and in the methods used in gathering the data. Such research, he argued, needed to be undertaken by an expert ‘familiar with modern anthropological methods’ rather than by colonial administrators – adding that, if so desired, he would be prepared to take on such a task. Thomas’s report shook the confidence of officials in the Colonial Office, and they took Thomas’s recommendations seriously. Following further consultation with senior anthropologists, including J. G. Frazer and C. H. Read, Thomas was duly engaged to carry out ‘an investigation of an experimental character into native law, custom, &c.’ in West Africa.

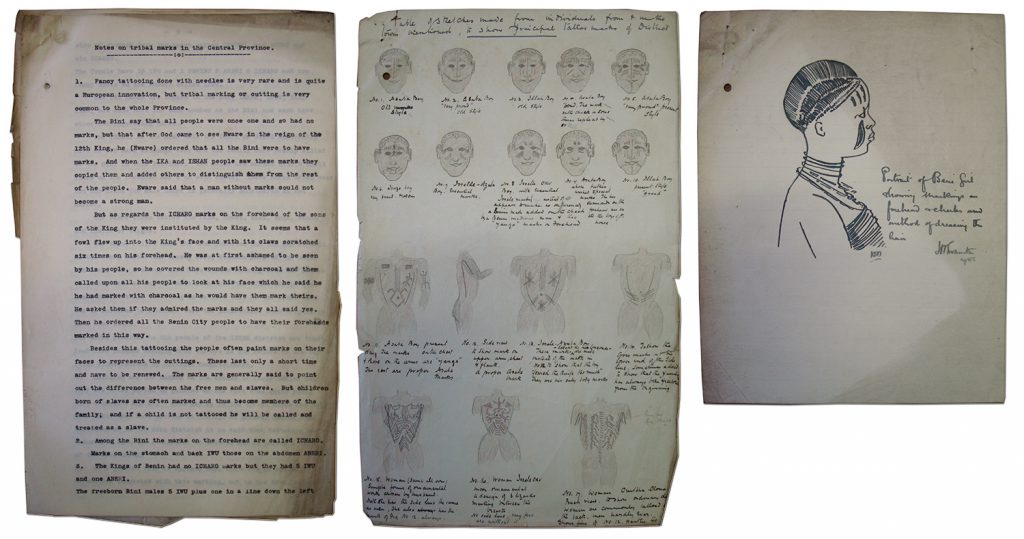

Of the governors of Britain’s West African territories, it was Sir Walter Egerton, Governor of the Colony and Protectorate of Southern Nigeria, who was most receptive to the idea of supporting the initiative to engage a professional anthropologist. It was thus agreed that the first ‘experimental’ anthropological survey should take place in Southern Nigeria. If the survey proved successful, it was agreed that the initiative would be extended, perhaps to other territories. It was important to note that Thomas was given little direct instruction either from the Colonial Office or colonial government in Southern Nigeria. Rather than focusing narrowly on specific problems or issues, Thomas embarked on a general ethnographic survey, following the guidance set out in the methodological handbook, Notes and Queries in Anthropology.

It is likely that Thomas chose Southern Nigeria’s Central Province as the focus of his initial tour due to his acquaintance with R. E. Dennett and H. N. Thompson, respectively the Deputy Conservator and Conservator of Forests in Southern Nigeria, who were ordinarily based in Benin City, the provincial headquarters. The companionship of Dennett and Thompson would, no doubt, have eased Thomas’s entry into what were, for him, the unknown worlds of both West Africa and the Colonial Service. Indeed, when his appointment was confirmed, Thomas requested that his departure for Southern Nigeria might be delayed until January 1909, so that he might travel out with Thompson, who had been on leave in England. The passenger list on the S. S. Burutu thus lists both N. W. Thomas and H. N. Thompson among its first class customers.

Further details about N. W. Thomas’s biography and career can be found in the article ‘N. W. Thomas and colonial anthropology in British West Africa: reappraising a cautionary tale’, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 22: 84-107.