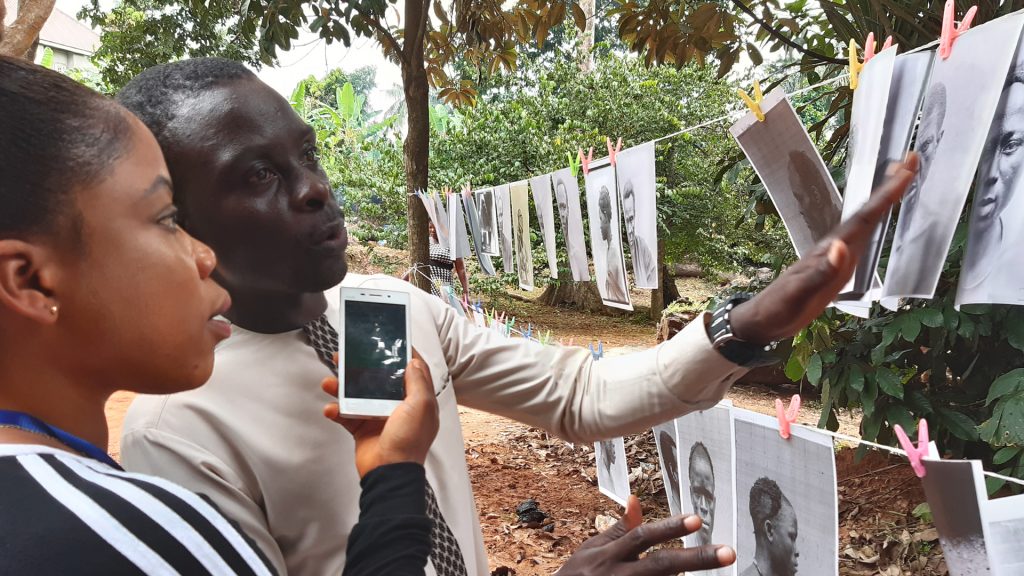

[Re:]Entanglements is part of a broader project entitled Museum Affordances, which is exploring what museum collections and archives make possible, or afford, for different stakeholders. As we have retraced the journeys made by the colonial anthropologist Northcote Thomas over 100 years ago in Nigeria and Sierra Leone, equipped with the photographs and sound recordings that he and his local assistants made, it has become apparent that one of the most powerful affordances of these archives is to enable people to reconnect with their ancestors. It has been a privilege for us to witness as community members set eyes upon the faces of their grandparents and great-grandparents, often for the first time.

Another striking affordance is the way these ancestral reconnections also connect extended families in the present. The descendants of those photographed during Thomas’s anthropological surveys now reside in many places throughout the world, forming transnational family networks among the broader diasporas of people with West African heritage. Social media platforms such as Facebook and WhatsApp enable such families to stay in contact, and it is interesting to see how the archive photographs that we bring back to communities in Nigeria and Sierra Leone are recirculated on these platforms, bringing extended families together through an appreciation of their shared past.

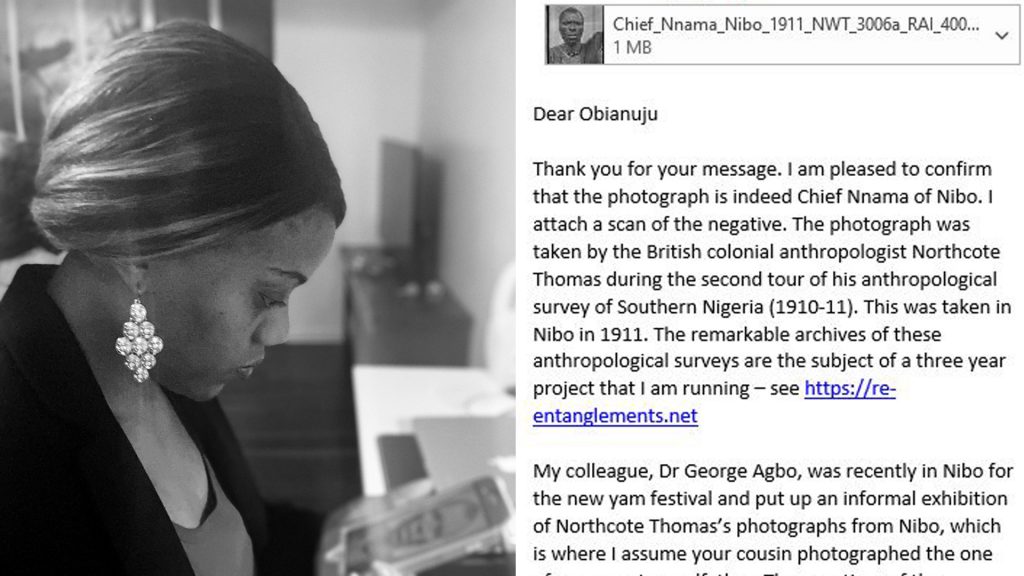

In October 2019, we were delighted to receive a message from Dr Obianuju Helen Okoye (née Nnama), a public health physician based in Chicago, Illinois, USA, sending us a photograph she had received from family members in Nibo in Anambra State, Nigeria. Dr Okoye – ‘Uju’ – wrote seeking confirmation: Was this really Chief Nnama, her late great-grandfather? It had been presented as such by a researcher from the [Re:]Entanglements project who had visited Nibo bearing the photographs.

In this guest blog, Uju tells the story of this ‘reunion of sorts’. Part family memoir, part eulogy for an illustrious ancestor, part local history, it is a rich and personal reflection on the contemporary value of these colonial-era archives.

Homecoming

The visitor from the University of Nigeria, Nsukka came unannounced, bearing precious gifts. ‘My name is Dr George Agbo’, he said in Igbo as he explained the purpose of his visit to the assembled group of Nibo indigenes. As he set up copies of Northcote Thomas’s 100-year-old photographs in an impromptu display, many of those gathered were somewhat bewildered. The exhibition of these portraits of strange-yet-familiar faces can best be described as a homecoming – an unexpected reunion of sorts, an intimate opportunity to embrace a past that was lost…

Staring at my phone in disbelief, I carefully examined the image that had pinged into our Nnama family WhatsApp group, which has over 50 members dispersed across West Africa, the UK and USA. My cousin, Chief Edozie Nnama (Ozo Odenigbo), had just shared a black and white photograph of a chiefly-looking man stating that it was our famous great grandfather. For the next two days there was confusion as we tried to make sense of what seemed to be an interesting rumour. How could we be sure? My cousin in the UK, Mrs Uzoamaka Nwamarah (nee Nnama), went off searching, and found the contact information for the [Re:]Entanglements project. So, to the source we went for confirmation, and I sent an email enquiry to Paul Basu, the leader of the project.

Fingers shaking, I took a screenshot of my email correspondence with Paul Basu, forwarding it to the family WhatsApp group. A mere ‘copy and paste’ seemed inadequate for news of such magnitude. For all of our Nnama family members – all who knew Nnama in the same manner that I did, as a revered name – it was the unearthing of a priceless family heirloom, made possible through the archival excavations undertaken by the [Re:]Entanglements project.

Nibo, my great-grandfather’s lands

Dusty red sand. Lush green tropical terrain. A bumpy ascent along untarred roads above the Obibia river. The joyous chants of children playing in the water below. My father’s loud voice bellowing, ‘These are my grandfather’s lands! These are all Nnama’s lands!’ These images remain ingrained in my mind. As a child I knew their significance. This was the land of my ancestors. It was my land. This place, Nibo, was home.

Nested in Igboland, on the banks of the Obibia river in Anambra State, Nigeria, Nibo lies close to its populous neighbour, Awka, with whom it shares a long history and close cultural ties. As children raised in various locations in West Africa and the United States, my father – Prof Samuel Kingsley Ifeanyi Nnama (Ozo Oyibo, Ozo Akaligwe, Ikenga Nibo-Traditional Prime Minister of Nibo, and the second in Nibo’s hierarchy at the time of his passing in 2016), who spent his childhood in Nibo and initially migrated to the United States in 1975 – made it a point to ensure that my siblings and I fully understood the legacy with which we had been entrusted. This was made especially tangible each Christmas during our childhood and teen years, when we would make an annual pilgrimage to our Nigerian hometown, Nibo.

Ezeike Nnama

Hearing the pride in my dad’s voice as he attempted to connect us, his children, with our mysterious and powerful ancestor – his grandfather, who he never actually knew in person – left a desire for a deeper understanding. Who exactly was this Nnama? How did he acquire his fame? What did he look like?

Since we had no photographs to look at, we created our own images in our minds. As I matured on another continent, thousands of miles from Nibo, my curiosity grew even stronger.

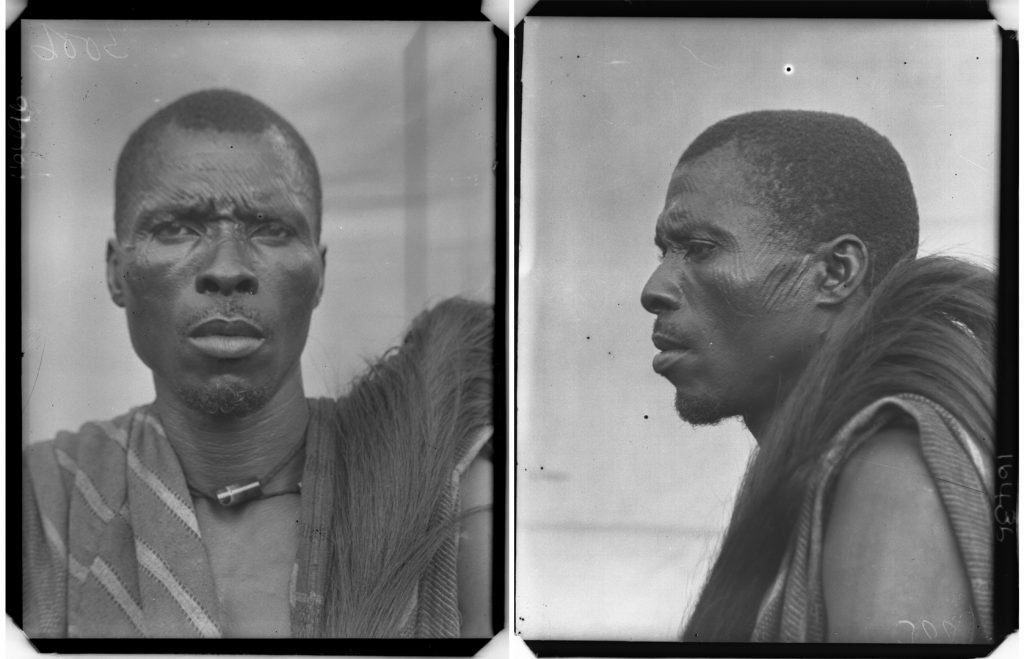

There he sits, with identifying facial marks and the nza over his shoulder. The scarification marks are called ichi – they signified royalty and status. The nza is a horsetail switch, which in those days formed part of the regalia of leadership. It is even used today by the current ruler of Nibo. His neatly-cut beard amazed me – what instrument, I wondered, did they use to maintain such neatness?

The photograph had a profound effect on me. I realized that while my dad has passed on his love for history and family to me, this image validated my connections. Nnama was more than a figure in a folktale – he was real! And the tears started flowing.

My late father was a keen family historian. This was a passion which he passed on to me at an early age. Back in 2007, we together created Wikipedia pages for Nibo and Chief Nnama to document their histories. Nibo is made up of four villages: Ezeawulu, Umuanum, Ifite and Ezeoye. Nnama Orjiakor was born sometime in the late 1860s/early 1870s into the royal family of Umuanum village. In the late 19th century there was a dispute between the ruling lineages of Umuanum and Ezeawulu, each claiming the throne. After decades of conflict (ogu uno), Umuanum prevailed and Nnama was confirmed as the Ezeike (king). To secure the peace, the opposing factions were united in the marriage of Nnama’s son – my grandfather – Orji Nnama and Mgbafor, the daughter of Ezekwe, the warrior leader of Ezeawulu village.

Ezeike Nnama Orjiakor was an astute strategist and formed an alliance with the powerful Aro warlord Okoli Ijoma of Ndikelionwu. Nnama arranged for his younger sister to marry Okoli’s second son Nwene Ijomah. In pre-colonial days, Nnama served as Okoli Ijomah’s deputy in the ‘Omenuko’ court, which presided over much of present-day Anambra State. This alliance offered Nibo great protection and safety during turbulent times.

With the coming of the British, however, Nnama recognized the futility of resisting the colonialist’s military might and the Nibo war council agreed to surrender. This marked the end of Nnama’s alliance with Okoli, who vowed that he would not be ruled by any other king and waged a military campaign against the British, suffering great losses and eventually putting an end to his own life rather than succumbing to the enemy. Meanwhile, Nnama was appointed as a Warrant Chief by the British in 1896 and continued to serve as Nibo’s traditional ruler until his death in 1945.

Nnama’s people

Northcote did not only photograph Chief Nnama when he visited Nibo in 1911. Inquiring further from Paul Basu, I was directed to a Flickr album containing almost 300 photographs he had made of people and places from my hometown. I was amazed to see my people in their natural habitat, often with remarkably intricate hairstyles that would be envied even today. As I looked through the photographs, I tried to connect the dots.

![[Re:]Entanglements project Flickr site](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/02/Reentanglements_Flickr_site_Nibo_screenshot_re-entanglements.net_-1024x576.jpg)

The photograph of Nnama begins the sequence of images that Northcote took in Nibo. The anthropologist would, of course, have gone to the king first. After taking Nnama’s picture, I reasoned that Nnama would then have arranged for Northcote to photograph other members of the ruling family. Prof Basu then sent me copies of Northcote’s photographic registers, allowing us to put names to the faces. Although the Igbo names were often incorrectly transcribed, I was hopeful that some of them might correspond with those recorded in our extended family (umunna) tree compiled by my late father.

In the photo register, after ‘Chief Nnama’ was ‘Oniyi’, who I couldn’t identify. But next was ‘Eke’. This was Nnama’s brother, whose descendants we all know. Then there was ‘Aduko’, which sounded so familiar. Could it be? Was it her? I wondered. Yes, this was surely Nwonye Oduko, my grandfather’s older sister, and Nnama’s first child.

Unfortunately, Aduko’s photograph is spoilt by a double-exposure. But, nevertheless, there she stands: Nnama’s ‘Ada’, his first child and daughter. Tall and seemingly full of pride, with scarification marks around her breast signifying her status as a daughter of the king. My dad had told me about his aunt Oduko, and the image made me smile.

‘Nwoze’, ‘Ekewuna’, ‘Ekwnire’, ‘Nweze’, ‘Ebede’, ‘Nwogu’, ‘Nwankwo’… these names I did not recognize, even taking into consideration Northcote’s errors of transcription. But then came ‘Nwanna’. Looking at the family tree, I saw there was indeed a Nwanna under the Ogbuefi branch of the family. I looked up the corresponding photograph and was stunned to discover that this Nwanna bore a striking resemblance to my dad’s older cousin, Chief Lawrence Ogbuefi, as well as his siblings, children and grandchildren. Other family members made the same observation.

In haste, I forwarded the image and a summary of my findings to Chief Lawrence’s daughter via WhatsApp. It was a remarkable discovery. For the Ogbuefi family members, looking at the photograph of Nwanna was akin to gazing in a mirror. For my Uncle Lawrence, aged 87 years old, this was a priceless heirloom. Nwanna was his father. He died when Uncle Lawrence was still young and my uncle had never before seen a photograph of him. After over 80 years, this image was a kind of resurrection that had him shedding tears of joy.

Uncle Lawrence wrote to me:

I salute the doggedness of the British anthropologist, Northcote Thomas, who visited my town Nibo in 1911 and took photographs of my people, including my dad – Nwanna Ogbuefi. I also salute the Royal Anthropological Institute and University of Cambridge for preserving those photographs for us. Those of us who were too young, even at our father’s death, to have any mental picture or reminiscences of what he looked like now have the opportunity of seeing what our dad looked like and appreciate the resemblances.

Northcote Thomas made trips to our land and made recordings that now establish a link with our fore-parents. Thomas may be long gone, but his work lives on to unite peoples of lost identities and educate and inform our children of the kinds of lives their great grandparents lived.

Travelling in time

To see Northcote’s photographs of Nibo carries us back to the Nibo of my grandfather’s childhood. To hear voices, recorded on Northcote’s phonograph, chanting songs in a pure Nibo dialect, stirs up a deep nostalgic feeling. As my cousin, Chief Nnamdi Nnama (Ozo Owelle) put it: It is an uncommon feeling, like one has travelled back in time to truly discover who you really are. Looking at the pictures said so much to me, and also left so much unanswered.

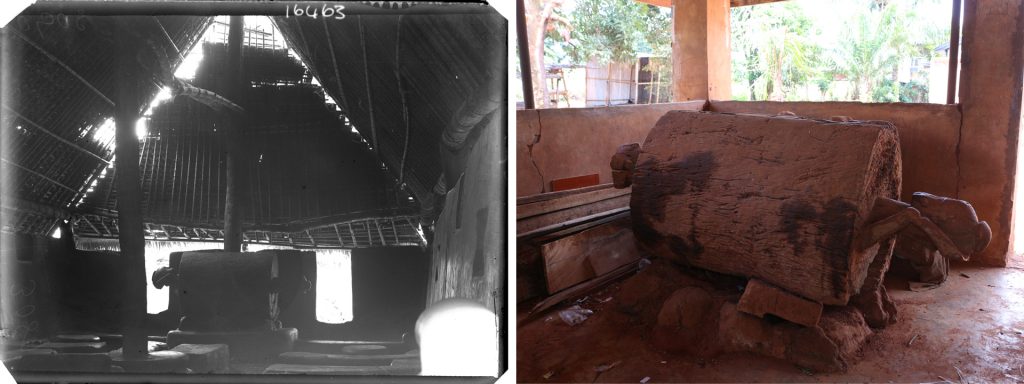

While much has changed in Nibo since Northcote’s visit, there are still traces of that time. Although faded over time, still standing is our famous uno nko nko – built over the site where our founding ancestor, Anum Ogoli, who established our village Umuanum was laid to rest. Inside can still be found the huge ikolo drum, which was also photographed by Northcote in 1911. The sound of this great drum could be heard at a great distance and the ikolo was used to communicate with the villagers.

The large tree that Northcote photographed, was still to be seen in my youth, when we took the short cut along the dusty path back to our house. And the obu, or court house, that Nnama’s father – Chief Orjiakor Eleh – built around 1856 remains an important landmark. (Nnama was buried just behind it.) Long gone, however, were the richly decorated walls that once enclosed the Ngene shrine.

My dad always told me that when the British came to Nibo, they came with a gun in one hand and a Bible in the other. Chief’s Nnama’s son, my grandfather, Orji Nnama, chose the Bible. He converted to Christianity, taking on the Christian name Joshua, and eventually became a missionary. This must have dismayed his father, since Nnama was not only the king, he was also keeper of the local gods, the chief priest of the Ngene shrine (Ngene Ukwu Afa), the biggest shrine in Nibo.

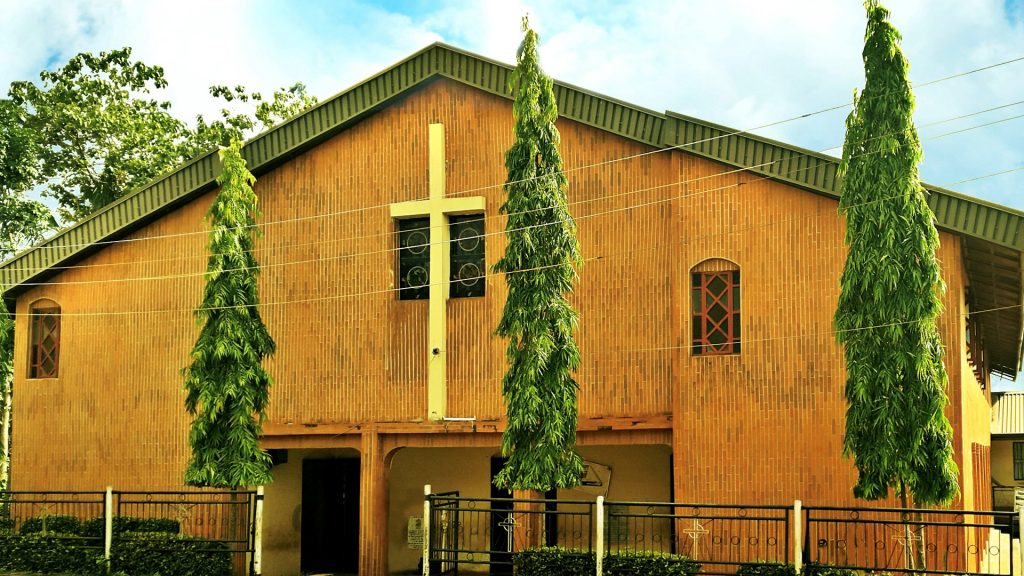

Even though Chief Nnama was a traditionalist he was also pragmatic. When his missionary son, now known to everyone as Rev Joshua, approached his father for land to build what would become St Matthew’s Anglican Church, Nnama rose to the task by offering his prized land at the very centre of the town – the Eke market square. A remarkable edifice that still stands today.

Rev Joshua also later built his own personal church on Nnama family land, All Saints Anglican Church. When the church needed to expand, the Nnama family donated the land on which the Ngene shrine once stood, and which had long-since become overgrown with bushes, to be the site of the new All Saints Anglican Church. In the passage of over a hundred years since Northcote photographed it, different religious institutions, the old exchanged for new, and yet the site is still sacred.

Since that fateful day when his face appeared on my phone, I often think about Ezeike Nnama. What would he think about his many descendants scattered around the world? What would he think of his town of Nibo today, with a new church prevailing where his traditional shrine once stood? I wish I could tell him that, though his descendants now serve a Christian God, we all stand tall with great pride in our rich legacy, because we know from whom we came.

Ancestral reconnections foretold

Reflecting on the significance of these ancestral reconnections, I want to leave the last words to my cousin, Chief Chibueze Nnama (Ozo Orjiakor VI, Ozo Nnama V), the current Nnama clan family head, who eloquently states:

I was elated, excited, amazed and joyous when we were informed of the interviews, records and pictures of our great-grandfather Chief Nnama Orjiakor (also known as Ozo Orjiakor II, Ozo Nnama I, Ofulozo, Alukachaa ekwe). This was awesome because in line with the cultural oral tradition of our forefathers: we, my brothers and sisters, children of Chief Godwin Chukwuedozie Davidson Nnama (Ofulozo), the first son of Rev Joshua Orjiakor Nnama (Ogbuaku), as teenagers and undergraduates, would sit down with our grandfather at the Obu Nnama Orjiakor while he relayed our entire family history, culture, taboos, African tradition religion, the coming of the white man and conquering of the Igbo tribes of the Lower Niger, slave trade, notable judgements as Warrant Chief, words of wisdom of his father, Chief Nnama Orjiakor and grandfather, Chief Orjiakor Eleh, the Warrior King. We were repeatedly told that our great-grandfather, Chief Nnama Orjiakor, was interviewed and the records were stored in the archives somewhere in Britain.

As the family historian and cultural custodian, it is awesome and uplifting that the truth of the records, culture and heritage of our great-grandfather, Chief Nnama Orjiakor, as foretold and repeatedly emphasised by our grandfather, Rev Joshua Orjiakor Nnama Ogbuaku, has come to light in our lifetime.

Thank you very much, Uju, for sharing your family’s remarkable story with us!