The areas in which Northcote Thomas worked as a Government Anthropologist in Nigeria and Sierra Leone have, of course, changed a great deal in the 105 years since the end of his last tour. During 18 months of fieldwork, retracing the itineraries of Thomas, we have, however, also been struck by the many continuities. Despite urbanisation and Christianity, cultural traditions are strong! Take chalk, for example…

Thomas’s reports and fieldnotes on the Edo- and Igbo-speaking communities that he researched between 1909 and 1913 are full of references to the use of chalk in rituals, ceremonies and customs. This chalk is known variously as ‘calabash chalk‘ and ‘kaolin‘. In Igbo it is nzu, in Edo orhue. As Thomas documented, this chalk is used in multiple ways – as an offering to the deities and ancestors, as a medicine, as a symbol of purity, of good fortune and hospitality. It is a sacred substance.

Rites of passage

Chalk is used in many ceremonies and rituals, from birth to death. For example, Thomas describes the initiation of boys into the Ovia society in Iyowa, north of Benin City. ‘The boy joins the society’, Thomas writes in an unpublished manuscript, ‘by payment of a calabash of [palm] oil, 20 yams, a calabash of palm wine, 4 kola and 5 legs of Uzo [duiker]. The yams are cooked and fufu is sacrificed to Ovia. The boy marks his face with chalk and is then called Oviovia or the son of Ovia’.

Thomas recorded a number of what he labelled ‘birth songs’ in his travels in what is now the north of Edo State. The Omolotuo Cultural Group interpreted a number of these when we visited Otuo, explaining that they would be sung when the newly born child was presented to the community. To celebrate, both the child and the community members would mark their faces with chalk or arue as it is called in the Otuo dialect. The Omolotuo Cultural Group performed such a song for us, marking their faces accordingly…

Title-taking and kingship

During our fieldwork in Okpanam, in present-day Delta State, Obi Victor Nwokobia explained that nzu is part of the paraphernalia associated with royalty, signifying blessing and purity. It is used in the coronation of a new king (obi) and to invoke ancestral blessings on his guests at the palace.

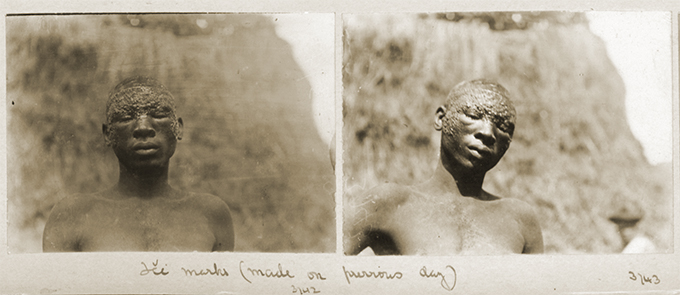

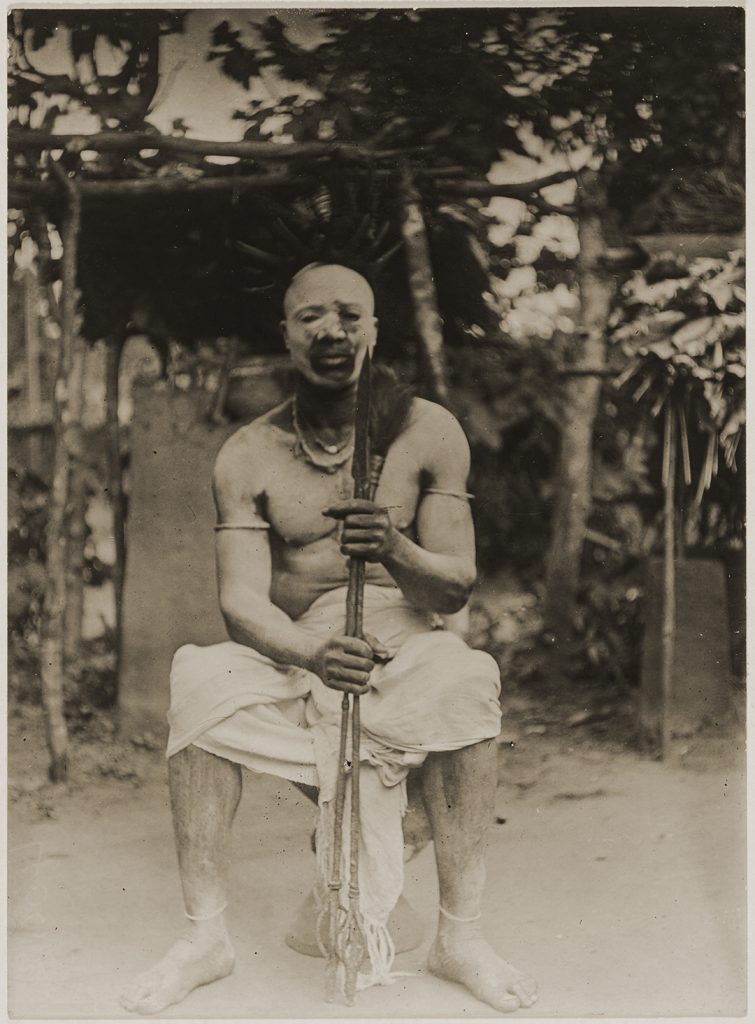

With others in Okpanam, Obi Nwokobia was particularly interested in a series of photographs Northcote Thomas took in 1912 of an individual he identified as ‘Chief Mbweze’. The name, we were told, should be written ‘Mgbeze’, and what the photographs record is his title-taking ceremony. Thomas does not state what title Mgbeze was receiving, though he lists the highest titles a man may attain in Okpanam as being eze and obu.

Obi Nwokobia explained to us the use of nzu in the obi/eze coronation ceremonies. Prior to the conferment of the title, the initiand is rubbed with chalk all over his body. He also wears a white wrapper. The white of the chalk and cloth represents purity and sanctification. The candidate must then spend a period of 28 days in isolation. During this time, the white of the chalk connects the initiand to the ancestors. When the candidate emerges from this period of seclusion, he is considered pure and to have received ancestral validation of his coronation. The newly titled man dances and throws nzu on the people gathered as a mark of blessing on them. It is a moment that Thomas captured in his series of photographs of Mgbeze’s title-taking. These same practices are used in the coronation of an obi today.

Seeing beyond the visible

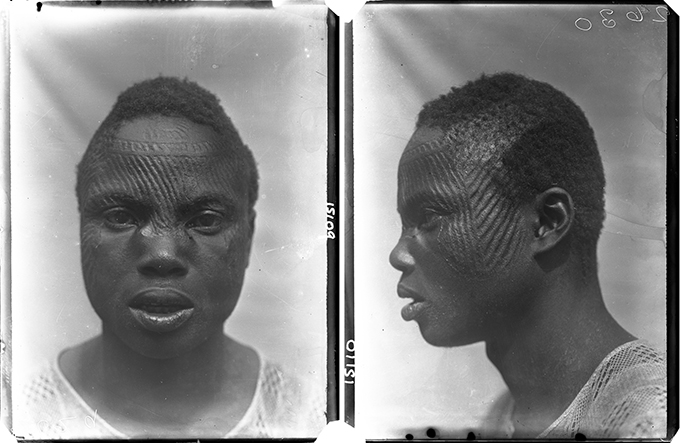

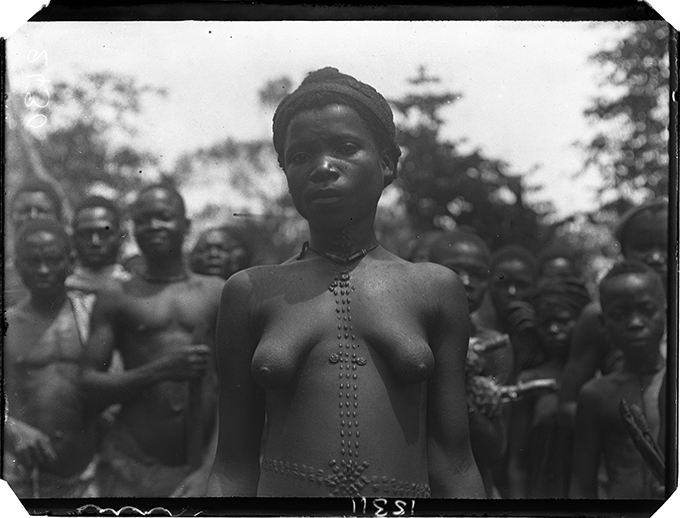

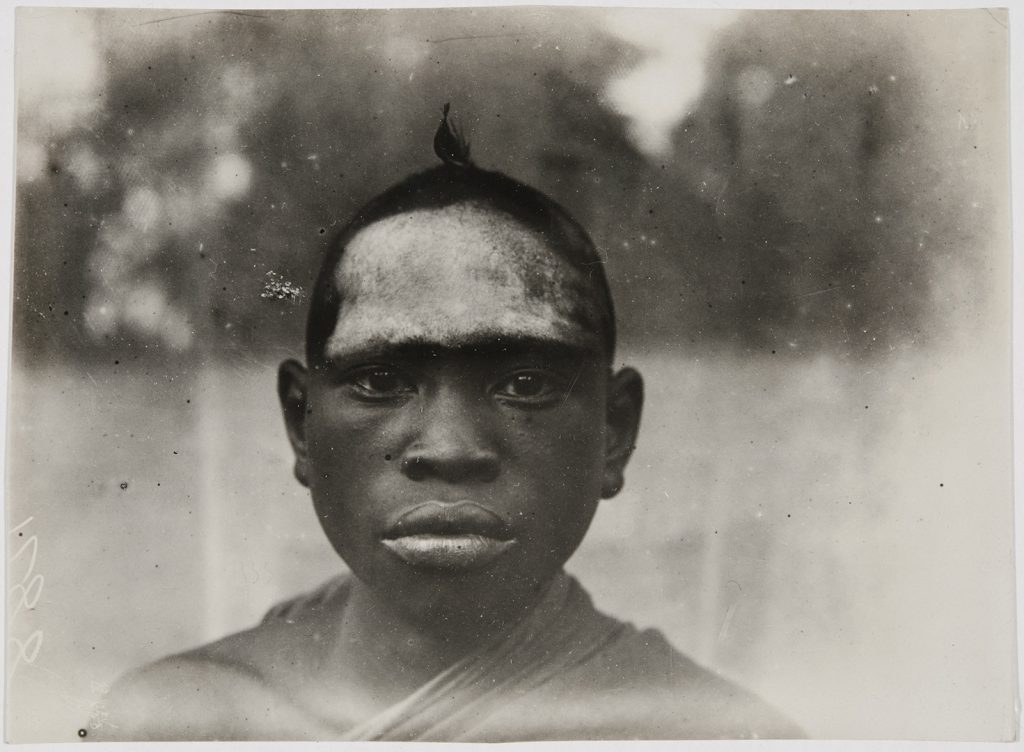

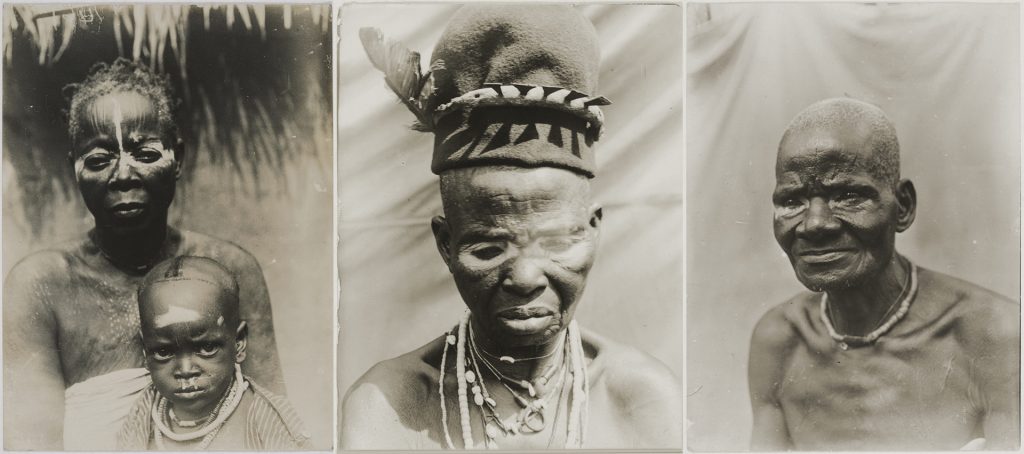

Among the hundreds of photographic portraits of individuals made by Thomas can be found many in which people have chalk smeared around one or both eyes. This could signify various things. The high female office of Omu, for example, was entitled to wear chalk around both eyes, as can be seen in Thomas’s photograph of the Omu of Okpanam (see centre photograph below).

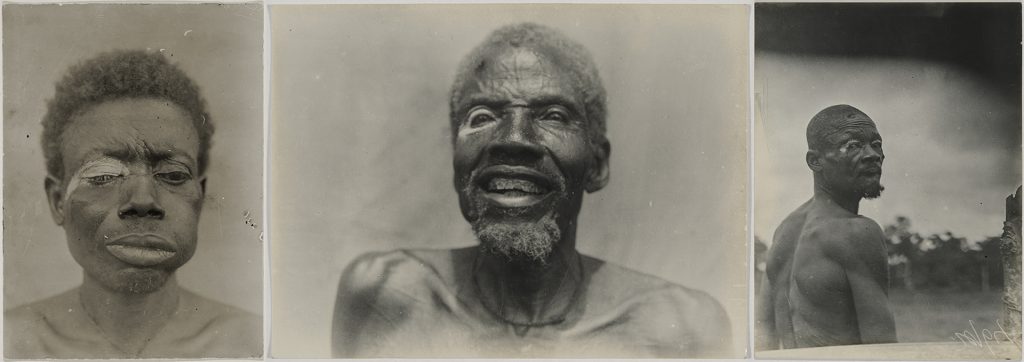

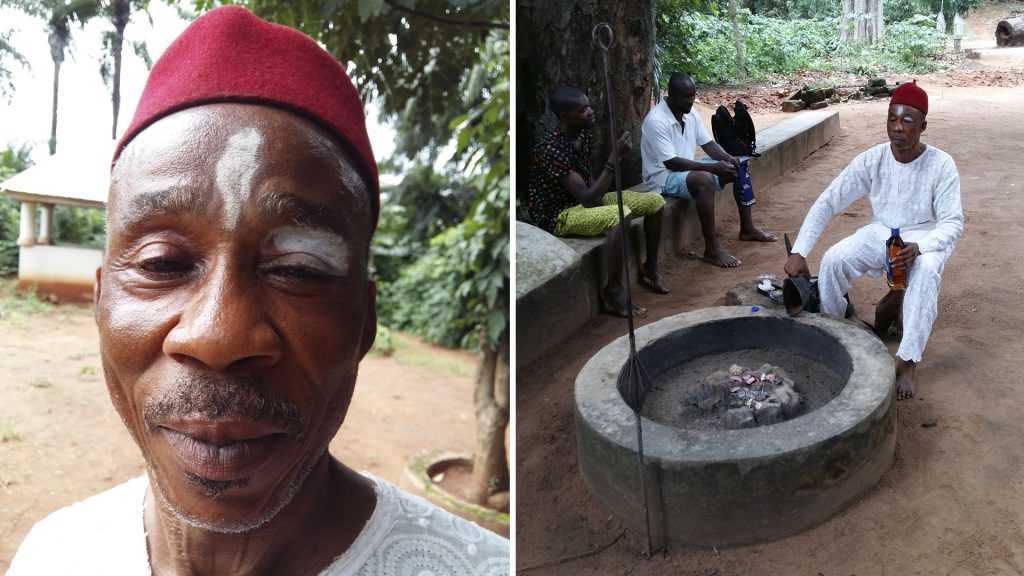

Thomas notes that native doctors (dibia) were also entitled to wear chalk around either one or both eyes, depending on their seniority. The same was true of priests. Chalk around the eyes signifies an ability to see beyond the visible world and into the world of the spirits. Chalk is still used in this way among traditional doctors, diviners and priests, as we have often encountered during our travels in Thomas’s footsteps. They are sometimes called dibia anya nzu, meaning ‘native doctor with the eye of chalk’.

When we met Paul Okafor, chief priest of the Nge-Ndo Ngene shrine in Nibo, Anambra State, he wore chalk on his forehead and left eyelid. He explained that the mark on his forehead granted him access into the spirit world, while that on his eyelid allowed him to see into the spirit world so as to be able to solve his clients’ problems. Okafor further explained that he must wash the nzu off before going to bed, or else he would not be able to sleep, but rather continue to commune with the spirits until the next morning.

According to Nwandu, a dibia we met at Ebenebe, he uses nzu as a medium to communicate with the ancestors. He also applies nzu to part of his eyelid to be able to see the spirit world, and he demonstrated for us how he draws chalk lines on the ground when performing spiritual consultations – igba afa – for his clients.

Ọgbọ obodo and the Mkpitime cult

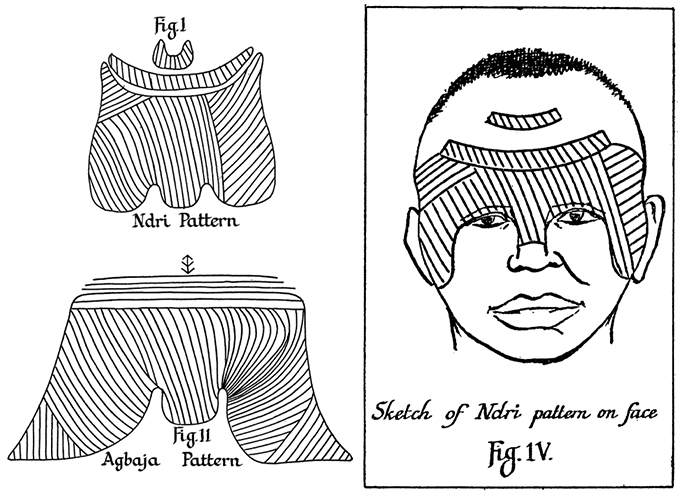

In the fourth part of his Anthropological Report on the Ibo-speaking People of Nigeria (1914), concerning the ‘laws and customs’ of the Western Igbo or Anioma people, Thomas provides an interesting account of the Nkpetime or Mkpitime cult. Mkpitime is the name of a female deity associated with a small lake close to Onitsha Olona, now Delta State, which Thomas visited in October 1912. Thomas evidently spent time with the orhene or priest of Mkpitime, a man named Mokweni, whom he also photographed. His visit coincided with the annual Iwaji (New Yam Festival).

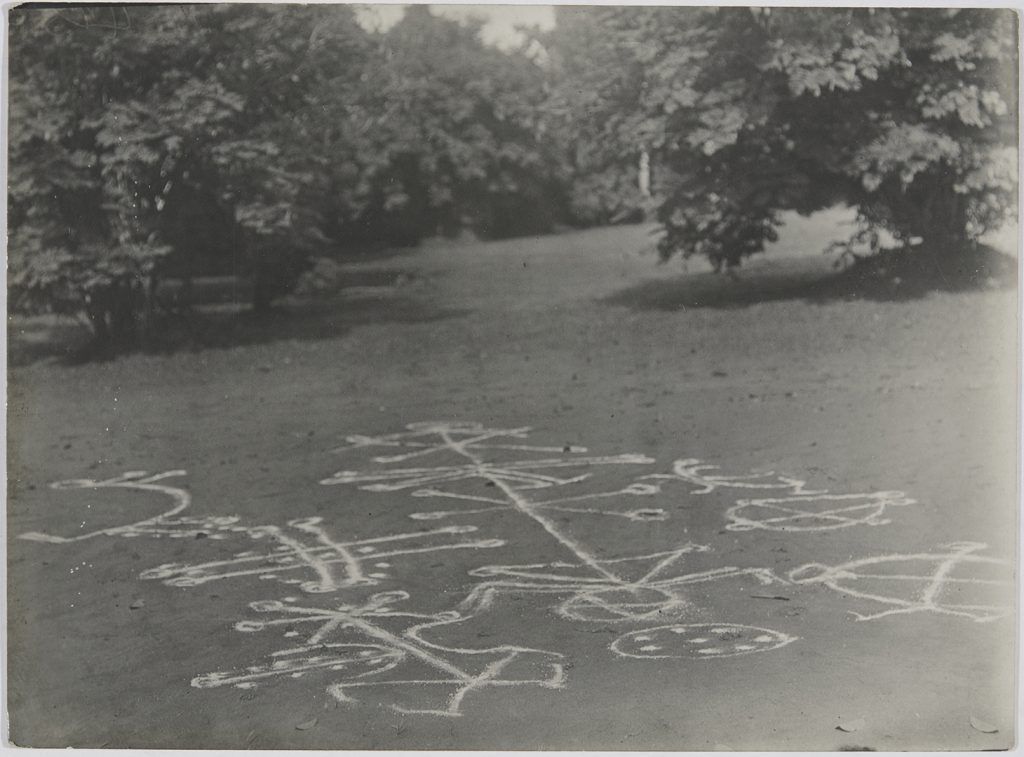

During the festival, the orhene is said to ‘go into nzu (chalk)’. This is a period of seclusion during which no one is allowed to make a noise, quarrel or fire a gun. Three days after going ‘into nzu‘, the orhene is supposed to make offerings at Lake Mkpitime and swim in its waters. On the fourth day, the orhene comes out of seclusion, accompanied by drumming and dancing before the mmanwu (spirits manifest as masquerades). Thomas describes how a woman created figures on the earth of the dancing ground using chalk, but also charcoal, red mud and ashes. Thomas notes that this is called obwo [ọgbọ] obodo – translating as ‘circle of dance’. The motifs represent various ‘totemic’ animals and other aspects of local cosmology, including a leopard, ‘tiger cat’, pangolin, monkey, viper, cross-roads, mirror, the sun, moon and Mkpitime herself. According to Thomas, domestic animals such as goats, ducks and fowls must not step on the figures. However, they are soon obliterated by the dancing feet of the celebrants.

Chalk at shrines

Chalk is associated with many deities throughout Southern Nigeria, including Ovia, Ngene and Mkpitime, mentioned above, but also Olokun, Ake, Imoka and others. Artist-educator, Norma Rosen, has written about chalk iconography in Olokun worship, for example, and some of the designs she discusses are not dissimilar to those Thomas photographed in Onitsha Olona. In an article Rosen wrote with the art historian Joseph Nevadomsky, the scene is described in which this ‘elaborately drawn chalk iconography’ is similarly ‘obliterated by dancing feet’, sending ‘vaporous messages fly[ing] back and forth … between the other world and earth’.

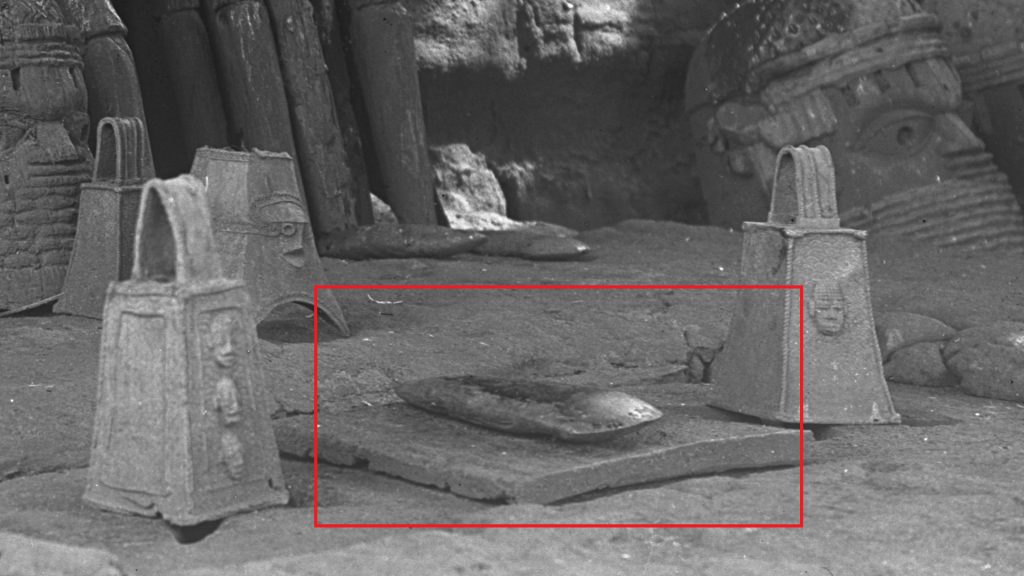

We witnessed something similar – and, indeed, participated in the dancing – when we visited the Ake shrine at Idumowina, on the outskirts of Benin City. We had created an album of Thomas’s photographs, which documented the shrine in 1909, and presented copies to the community and the Ake priest. A special ceremony was held in which the album was presented to the deity. As can be seen in the photograph above, adjacent to the altar was a pile of molded chalk blocks and a dish of powdered chalk. The powdered chalk was sprinkled on the altar on which the album was placed, and was used to create patterns on the ground, which were subsequently erased by our dancing.

In his fieldnotes about the Ake Festival that he documented at at Idumowina in 1909, Thomas describes how women would come to the shrine asking the deity to bless them with children, and also to thank the deity if they had recently given birth. (Ake, like Olokun, is a deity associated with fertility.) He records that children were given chalk to eat.

Indeed, chalk is traditionally ingested by pregnant women and as a medicine for various complaints. We have eaten nzu, too, during our fieldwork, after seeking blessings at the Imoka shrine, during the Imoka Festival in Awka.

A symbol of goodwill, friendship and hospitality

In some areas of Igboland, nzu is used instead of or alongside kola-nut in traditional hospitality ceremonies. The most senior man or traditional priest will draw or sprinkle lines of chalk on the ground while uttering a prayer. The number of lines drawn is often four, corresponding to the four deities or market days of the week – eke, oye, afo and nkwo. The prayer is addressed to Chukwu (the supreme God), lesser deities and the ancestors, asking for long life, wealth, peace and fairness. At the end of each prayer, those present will respond by saying Ise!

After the prayer, the chalk will be rolled across the ground from the feet of one person to the next in order of seniority (and social/geographical proximity to the host). It is important that the chalk is not passed hand to hand. Each will then make a mark on the ground before him, again often four lines. Ozo title holders are entitled to mark eight lines. Before rolling the nzu to the next person, each will take a small piece of chalk and mark one of their feet, or an eyelid and put a little in their mouth.

Further reading

- Nevadomsky, J. & N. Rosen, 1988. ‘The Initiation of a Priestess: Performance and Imagery in Olokun Ritual’, The Drama Review 32(2): 186-207.

- Rosen, N. 1989. ‘Chalk Iconography in Olokun Worship’, African Arts 22(3): 44-53.