On 21 September 2019, the [Re:]Entanglements: Contemporary Art & Colonial Archives exhibition opened at the National Museum, Lagos. The opening event was attended by an estimated 300 people, including many from Nigeria’s vibrant arts scene. Following on from our successful exhibition in Benin City, this collaboration between the [Re:]Entanglements project, the National Museum, and the Lagos-based artist Kelani Abass continues our exploration of artistic engagements with the archival traces of Northcote Thomas’s anthropological surveys.

![Scenes from opening of [Re:]Entanglements exhibition, National Museum, Lagos](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/National_Museum_Lagos_exhibition_opening_re-entanglements.net_.jpg)

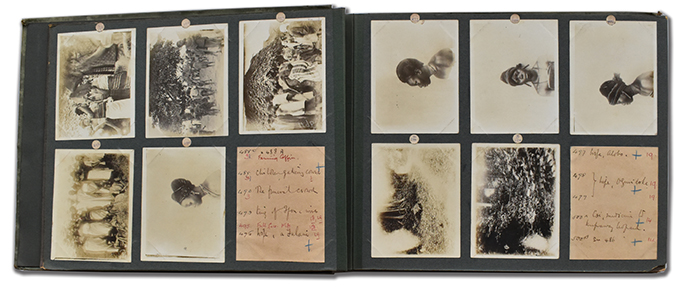

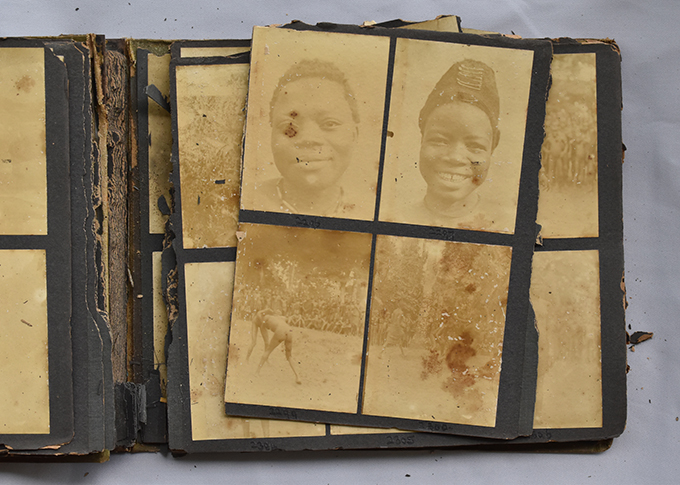

Unlike the Benin exhibition, this initiative focused specifically on the photograph albums from Thomas’s three Nigerian surveys, which we have discovered in the National Museum library and archive collections. Indeed, these albums, dating from 1909 to 1913, appear to be the only substantial archival traces of Thomas’s anthropological surveys to have survived in Nigeria. The initiative is also different insofar as it features the work of a single artist rather than a collective.

Over the course of a year, Kelani Abass has produced two series of works for the exhibition under the common title of Colonial Indexicality. These both employ techniques developed in earlier works by Abass, including his Calendar and Stamping History series, first exhibited at exhibitions at the Centre for Contemporary Art, Lagos in 2013 and 2016 respectively. In both of these series, Abass explored a more personal history through sifting through the archives of his parents’ printing business in Abeokuta, incorporating both the technologies of hand-operated letter-press printing and the accumulated materials – photographs, leaflets, design motifs – deposited at the press by customers. The Colonial Indexicality series produced for the [Re:]Entanglements exhibition connects this family history with a broader cultural history as refracted through Northcote Thomas’s colonial anthropological lens.

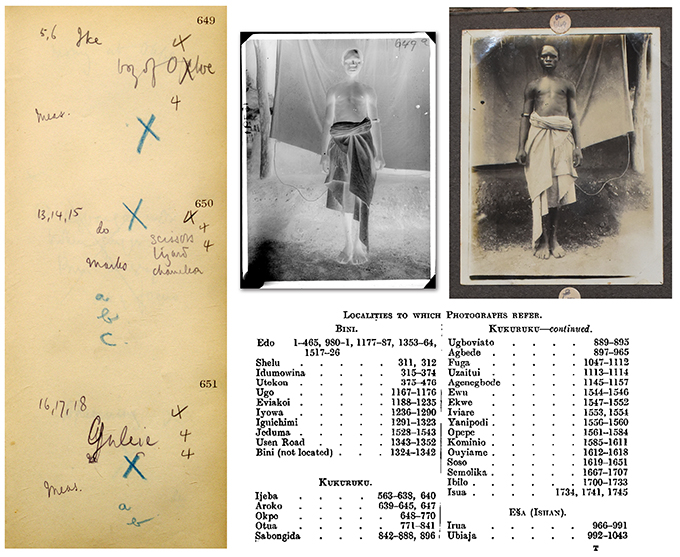

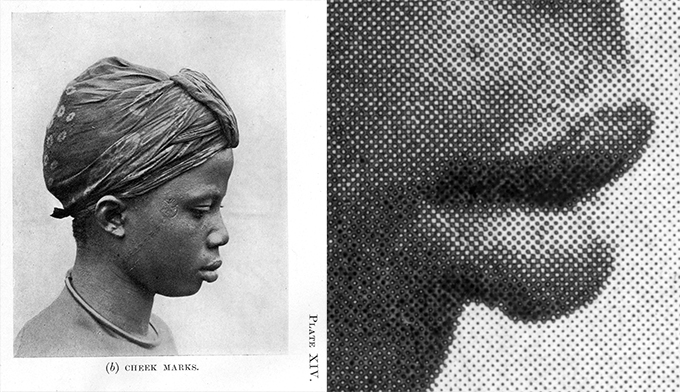

The pervasiveness of numbering systems and indexes are, of course, characteristics of all archives, and the archives of Thomas’s anthropological tours are no exception. Thomas numbered each of his photographic negatives, for example, and he made notes about each negative in a series of pre-numbered photographic register books. Most literally, the negative number acts as an index in relation to corresponding prints, but also indexes other information, for instance, the identity of the person photographed, where the photograph was taken, and places the particular photograph in relation to a sequence. We know, for example, that Thomas’s negative number 649 is of a boy named Ike, and is one of a series of 122 photographs that Thomas made in Okpe in present-day Edo North in 1909. There is a further note in the corresponding photographic register – ‘meas.’ – short-hand for ‘measurement’, recording that Thomas also recorded Ike’s anthropometric measurements, indexing how this young man entered other forms of colonial scientific calculation.

It is no surprise, then, that the theme of numbers and numbering emerges prominently in Abass’s artistic responses to the albums in the National Museum. Indeed, each work in the Colonial Indexicality series bears a simple number as its title – the number of the particular photograph the work itself indexes.

![[Re:]Entanglements exhibition view, National Museum, Lagos](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/National_Museum_Lagos_exhibition_view_re-entanglements.net_.jpg)

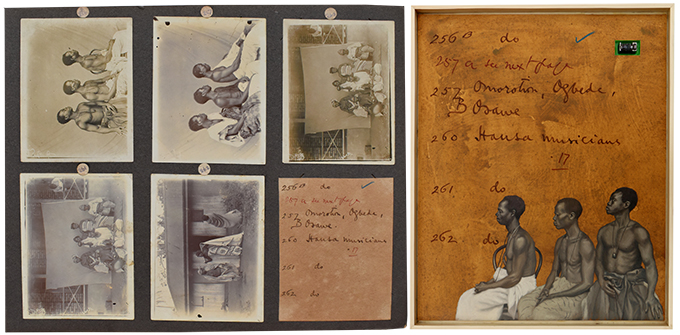

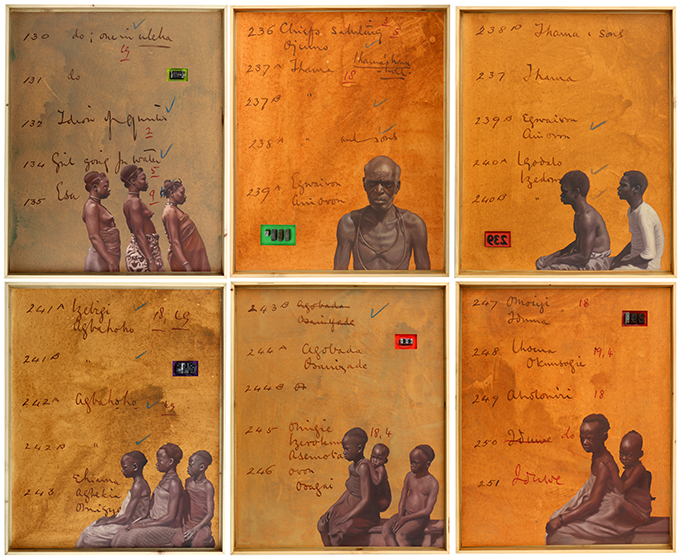

The principle of indexicality is also evident in the very grammar of the exhibition. In the first room of the exhibition, we brought three elements into relation: examples of the original photograph albums from Thomas’s 1909-10 Edo tour; enlarged digital prints of a selection of pages from these albums; and a series of 12 mixed media paintings by Abass that respond to the particular qualities of these albums.

The pages of the Edo albums are arranged in a uniform manner, with five photographs in a grid with a paper index panel cut to the same size as the prints and pasted in the grid. For each of the 55×68 cm paintings, created in acrylic and oil on canvas, mounted onto board, Abass reproduces these index panels as his backgrounds. He captures the ‘texture’ of the yellowed parchment-like paper panels, complete with Thomas’s handwriting and various other ticks, annotations and crossings-out that have been added in different coloured inks. He then selects one of the photographs from the same album page, which he paints in tones which evoke the photographic originals. The number of the photograph is used as a title for the work, which is also inset into the painting either using letterpress types or components of a numbering machine.

In the second room of the exhibition, the juxtaposition of original archives, digital prints and Abass’s contemporary artworks continues. Additional themes of disintegration and dissolution are invoked here, pointing to the fragility of the archive and the impermanence of memory. In one 105×127 cm digital print of an album page from Thomas’s 1912-13 tour of Igbo-speaking peoples, for example, the faces in Thomas’s physical type photographs have faded to little more than ghostly impressions. Indeed, one objective of the exhibition was to draw attention to the urgent need for better storage and conservation of the National Museum’s important archival collections.

![[Re:]Entanglements exhibition view, National Museum, Lagos](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/National_Museum_Lagos_exhibition_view_2_re-entanglements.net_.jpg)

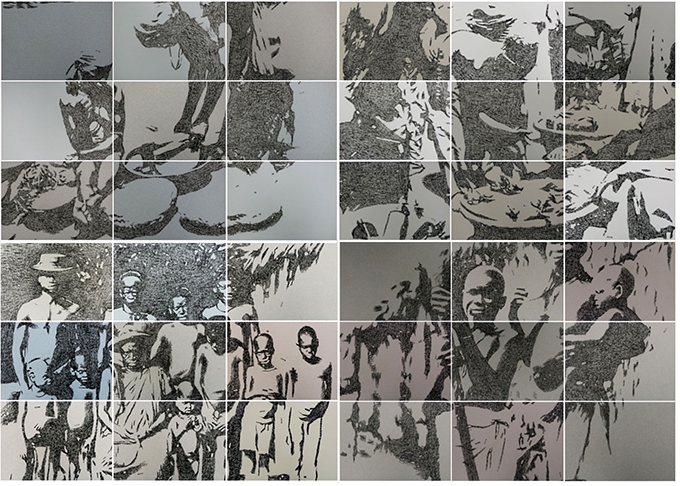

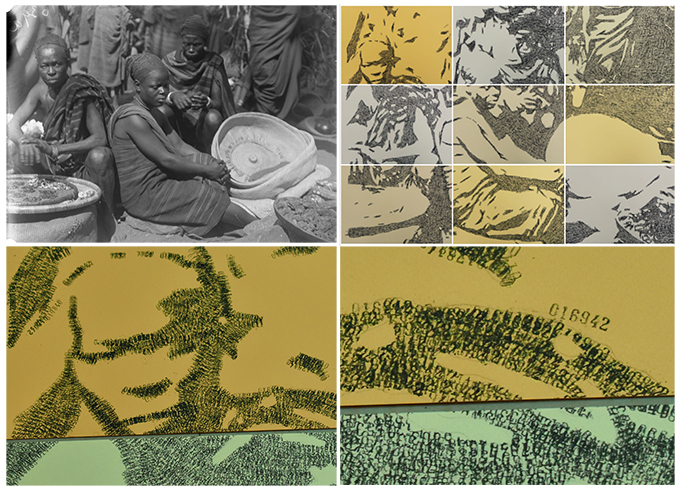

Abass refers to the second series of works in Colonial Indexicality as a continuation of a ‘performative oeuvre’ that ‘calls attention to the interplay of manual and mechanical processes involved in the production of printed works, photographs and drawings’. This work comprises of five interlinked 126×90 cm ‘drawings’ of Northcote Thomas photographs, which have been laboriously made using a hand numbering machine.

The use of the numbering machine as a medium again relates to Abass’s family history and childhood memories. After a day at school, Abass and his siblings would help out in their parents’ print shop, using these automatic numberers to stamp sequences of numbers in newly printed invoice books and other stationery. In relation to the [Re:]Entanglements project, Abass was struck by the sequential printed numbers evident in the stationery used by Northcote Thomas. Indeed, to create these ‘stamping history’ drawings he used stamping machines with a similar font style to the numbers used in Thomas’s photographic registers.

The numbers that Abass stamps in these works are not arbitrary either. They index both the specific photographs from the Thomas archives that Abass reproduces, but also act as a form of accountancy, allowing Abass to quantify his artistic labour and reflecting the labour entailed in producing the anthropological archive in the first place. Thus, Abass’s first impression in this work was the number 1155, corresponding with Thomas’s negative number 1155. After each impression, the number on the stamping machine increases by a digit to 1156, then 1157 and so on. At the end of the process of creating these five works, the final number stamped was 85,867. Thus Abass is able to quantify the work as representing 84,710 acts of stamping – this Abass conceptualises as a process of ‘stamping history’, and of ‘making or marking time’.

The grid-like layout of these five ‘drawings’ echoes the layout of the photographs in Thomas’s albums, but also speaks to the fragmentary nature of the archive – an assemblage of parts that must be assembled together in order to make sense. The actual archive is rarely so complete, and the bigger picture is often based on as much conjecture as it is evidence.

It is, of course, only when one stands back from Abass’s large-scale stamped drawings that the picture, quoted from Thomas’s archive, becomes clear. Up close, one sees a mess of over-lapping stamped numbers. Seen from a distance, however, the individual numbers from which the pictures are made disappear and the eye perceives the pattern. It is the same principle as halftone printing – the technique used to print Thomas’s photographic plates in his published reports (a set of which also resides in the National Museum library). Indeed, the same principle applies to Thomas’s original photographic negatives and our digital scans of them today, in which the coating of granular light-sensitive crystals is translated, imperfectly, into pixels. Switching to a metaphorical register, Abass’s work reminds us that what we perceive in the colonial archive depends on where we stand, as well as how close we look.

[Re:]Entanglements: Contemporary Art & Colonial Archives is open at the National Museum, Lagos until 27 October 2019. Do go along if you can and let us know what you think!

Read Molara Wood‘s review of the Colonial Indexicality exhibition in The Lagos Review.

This is interesting… congrats prof Basu and kelani Abass.