The painstaking archival and collections-based research made possible through the Museum Affordances / [Re:]Entanglements project enables us to make novel connections between objects, images, texts and sounds, and opens up new avenues of understanding. Working with the material legacies of Northcote Thomas‘s anthropological surveys in West Africa provides insight into cultural practices of the past, challenges assumptions about colonial collecting, and presents possibilities for creativity and collaboration in the present.

When we first examined a remarkable assemblage of 39 carved wooden ukhurhẹ staffs in the Northcote Thomas Collection at the University of Cambridge’s Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology in 2018, we were immediately struck by the freshness of their appearance. As far as we know, they have never been on public display and they had the appearance of coming straight from the carver’s workshop – despite being at least 110 years old.

Brian Heyer provides a succinct summary of such ‘rattle-staffs’ in Kathy Curnow’s book Iyare! Splendor & Tension in Benin’s Palace Theatre. He writes,

When an Ẹdo man dies it is his eldest son’s duty to commission an ukhurhẹ in his honor. He then places it on the family altar as the only essential ritual object there. An ukhurhẹ consists of a wooden staff divided into segments designed to resemble the ukhurhẹ-oho, a bamboo-like plant that grows wild near Benin City. Each segment represents a single lifespan, and linked they are a visual symbol of ancestry and continuity. Their mass numbers on altars stress the importance of the group over the individual.

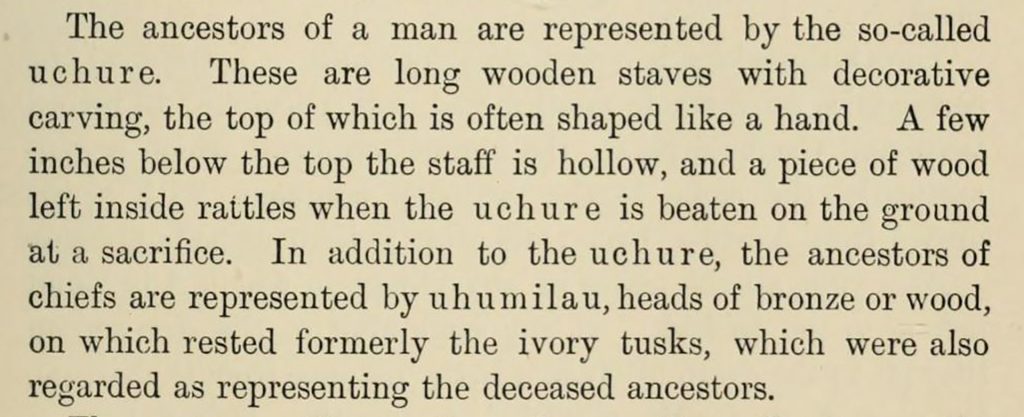

The top segment of the ukhurhẹ is hollowed by slits, a wooden piece remaining within. This acts as a rattle when the staff is stamped on the ground, a sound said to call the ancestors.

Ukhurhẹ topped by heads are standard for commoners and chiefs. Royal family members’ examples end in hands or hands holding mudfish. Only the Oba’s ukhurhẹ can be made from brass or ivory, though even most of the royal staffs are usually wooden, made by the members of the Igbesanmwan royal carving guild.

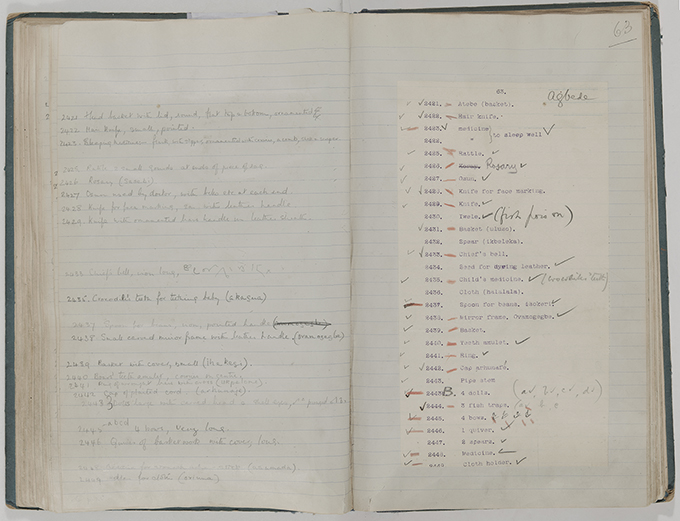

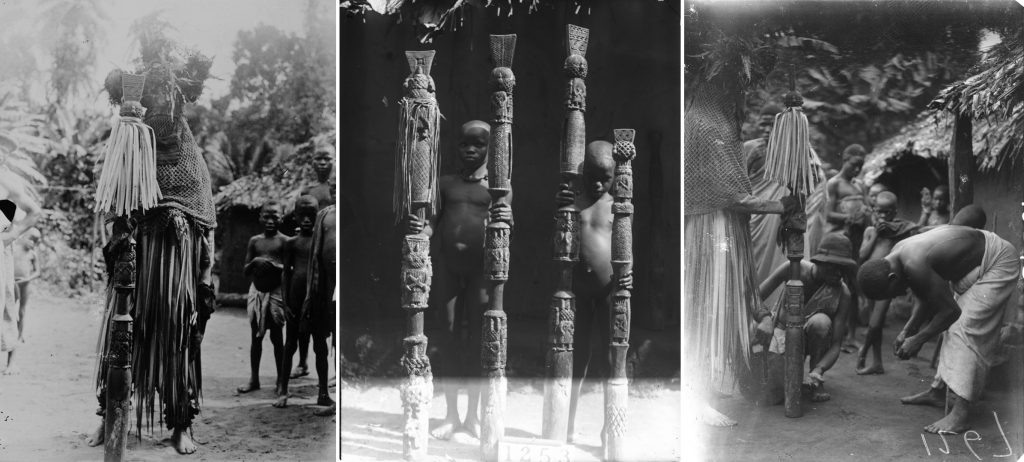

Northcote Thomas encountered these ukhurhẹ staffs during his 1909-10 anthropological survey of the Edo people of Southern Nigeria. They were – and, indeed, still are – an important part of the ancestral altars located in chiefly families’ palaces and compounds. Thomas photographed a number of such altars in Benin City itself and in the wider region. In Uzebba, for instance, Thomas noted that ukhurhẹ (which he spelled uxure or uchure) were known as ikuta, but fulfilled a similar memorial function – presencing the ancestors.

In his Anthropological Report on the Edo-speaking Peoples of Nigeria, published in 1910, Thomas explains that these staves – also widely known as rattle-staffs – represent particular male ancestors. They are placed on the family altar after the death of the family head, once he has transitioned into the status of an ancestor. The ukhurhẹ is a manifestation of the ancestor’s spirit, and the family make sacrifices to the ukhurhẹ to honour and seek the intercession of their departed kin. Over the generations the staffs accumulate, alongside other altar objects such as ivory tusks, memorial heads, bells and stone celts.

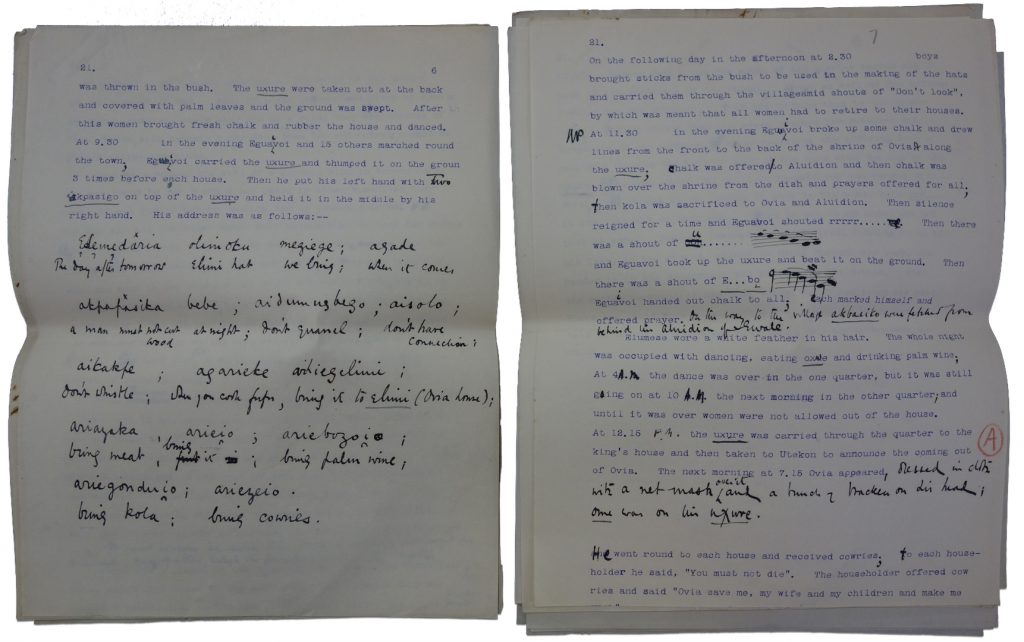

In unpublished notes, Thomas describes the practices surround the ukhure in greater detail. He describes, for example, Chief Ero‘s yearly sacrifice to his ancestors in which the blood of sacrificed cows, goats and fowl was smeared on the staffs. He describes how the ukhurhẹ propped against the wall at the ‘shrine of the father’ in Chief Ezomo‘s compound were stained dark brown due to these ‘repeated outpourings of blood’. He also reports that Ero could only give the names of two of the ancestors represented by the staffs, suggesting that the massed staffs come to represent the ancestors in a more collective sense.

In addition to the rattle-staffs found on ancestral altars, Thomas also documents the use of larger, more elaborately carved ukhurhẹ of community cults associated with various divinities. In October 1909, Thomas spent several days observing the festival of the Ovia cult in the town of Iyowa, a few miles north of Benin City. He documented the ceremonies, songs and dances in great detail. (This will be the subject of a future article). The ukhurhẹ of Ovia plays a central part in the festival as a manifestation of the deity itself. The figure on the top of the ukhurhẹ has the same form as the Ovia masquerade, which carries it.

Forty-four years after Northcote Thomas documented the Ovia Festival at Iyowa, another anthropologist – R. E. Bradbury – made a study of the same festival at Ehor, another village on the northern outskirts of Benin City. Bradbury writes that the ukhurhẹ ‘are the real symbols of Ovia’; ‘they are about four and a half feet high, carved with representations of the Ovia masquerades. They, more than anything else, are identified with Ovia herself who is sometimes said to enter them when she is called upon by the priests’.

In The Art of Benin, art historian Paula Girschick Ben-Amos explains that the ukhurhẹ of these ‘hero deities’ are ‘different from the more commonly seen ancestral staffs, as they are much thicker and have the figure of a priest or other objects specific to the cult as a finial’. ‘The rattle staff,’ she writes, ‘is both a means of communication with the spirit world, achieved when the staff is struck upon the ground, and a staff of authority, to be wielded only by properly designated persons’.

It is interesting to note that Thomas did not collect any ukhurhẹ that had actually been used in rituals either on ancestral altars or in cult ceremonies. And this brings us back to our initial impressions of the assemblage of ukhurhẹ we encountered in the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology stores in 2018.

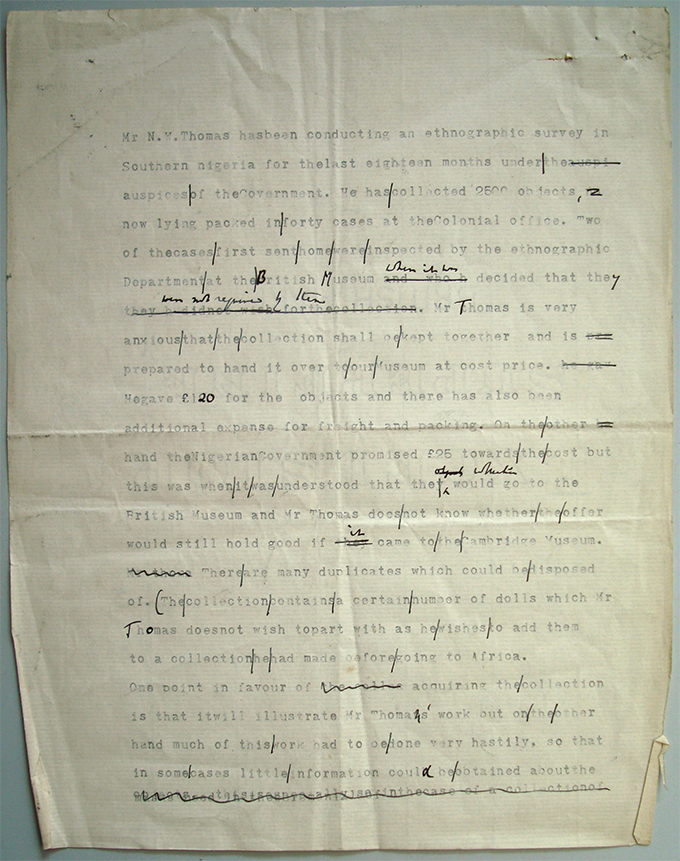

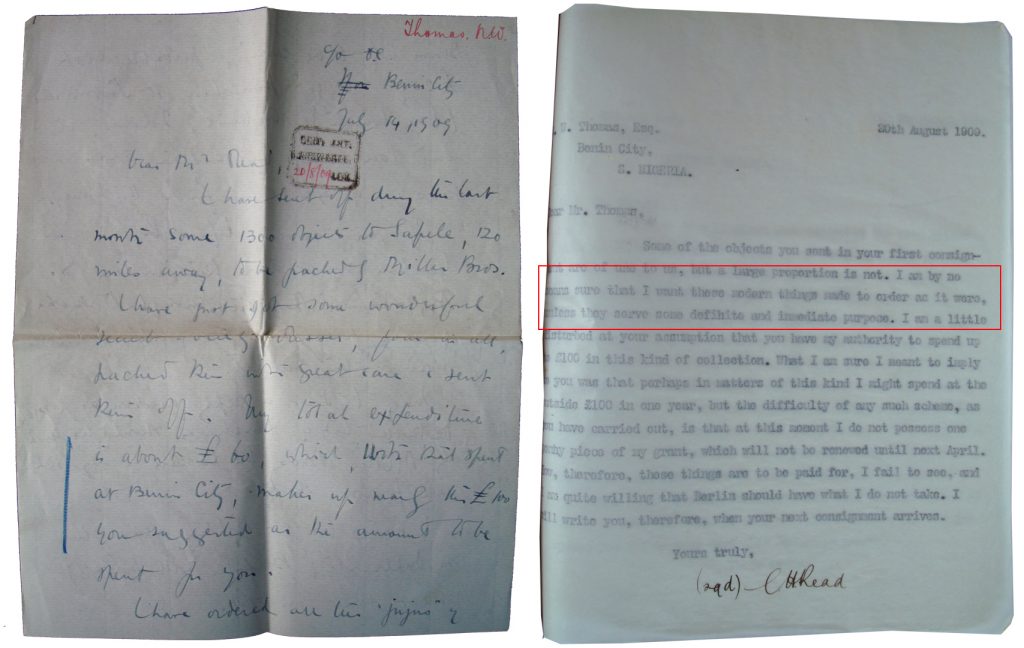

Prior to our examination of the staves we had found an intriguing exchange of letters between Northcote Thomas and Charles Hercules Read, who, in 1909, was Keeper of British and Medieval Antiquities and Ethnography at the British Museum. The letters show that Thomas was under the impression that Read had agreed to acquire the collections he had been gathering during his survey, reimbursing his initial outlay in purchasing them. It is clear, however, that Read was not interested in the kinds of ‘ethnographical specimens’ that Thomas was collecting. Writing from Benin City in July 1909, Thomas explained, for example, that ‘I have ordered all the “jujus” of Benin City to be carved, probable cost £25’. Read replied in August that ‘I am by no means sure that I want these modern things made to order as it were, unless they serve some definite and immediate purpose’.

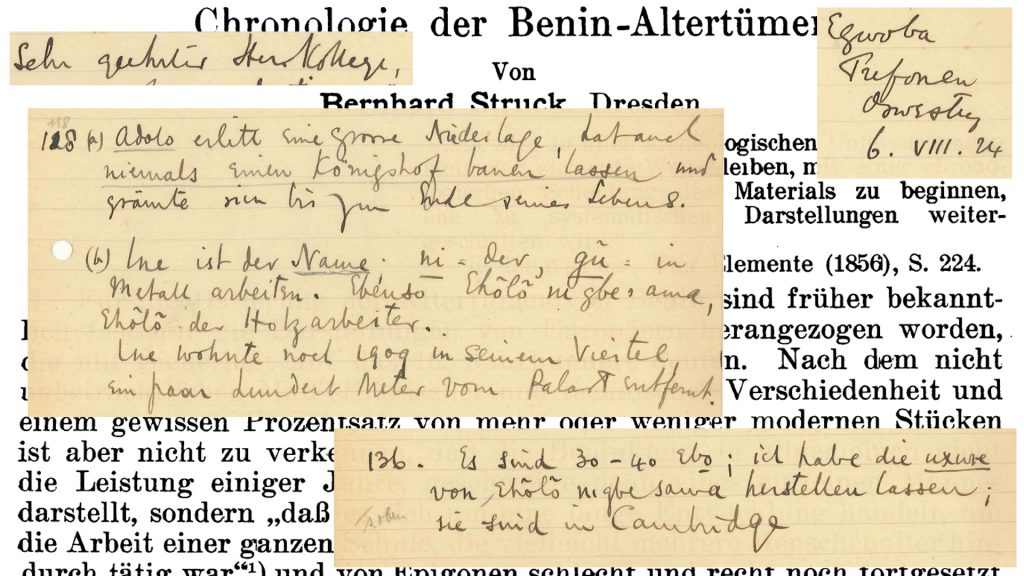

Given the freshness of the carvings, we suspected that the carved ‘jujus’ Thomas refers to in this letter were the ukhurhẹ staffs, each surmounted with a figure representing a different deity or ebo. Confirmation of this came, by chance, a couple of years later, when we found a further reference to the carvings in correspondence between Thomas and the German anthropologist Bernhard Struck, curator at the Museum für Völkerkunde in Dresden. Thomas and Struck maintained a professional correspondence over many years and, in a 1924 letter sent from his home near Oswestry, Thomas provides detailed corrections and comments on an scholarly article Struck was evidently working on. In a digression, Thomas notes that ‘There are 30-40 ebo; I have commissioned [herstellen lassen] the uxure from Eholo nigbesawa. They are in Cambridge’.

Elsewhere in the same letter, Thomas explains that ‘Eholo nigbesawa’ means Eholo the woodworker [Holzarbeiter]. In fact, however, Eholo is the title given to the head of the wood and ivory carvers’ guild, the Igbesanmwan – and the name/title should be Eholo N’Igbesamwan. It seems, therefore, that Thomas commissioned the ukhurhẹ from Eholo N’Igbesamwan and they were either carved by him personally or by other members of the guild. According to the Historical UK inflation rate calculator, the estimated cost of £25 corresponds to approximately £2850 today, so this would have been a significant and lucrative commission.

The story of how the ukhurhẹ were obtained is important, not least since it challenges stereotypical assumptions that colonial-era collectors such as Thomas either looted objects from sacred sites or else exploited local craftspeople by paying paltry sums for their work.

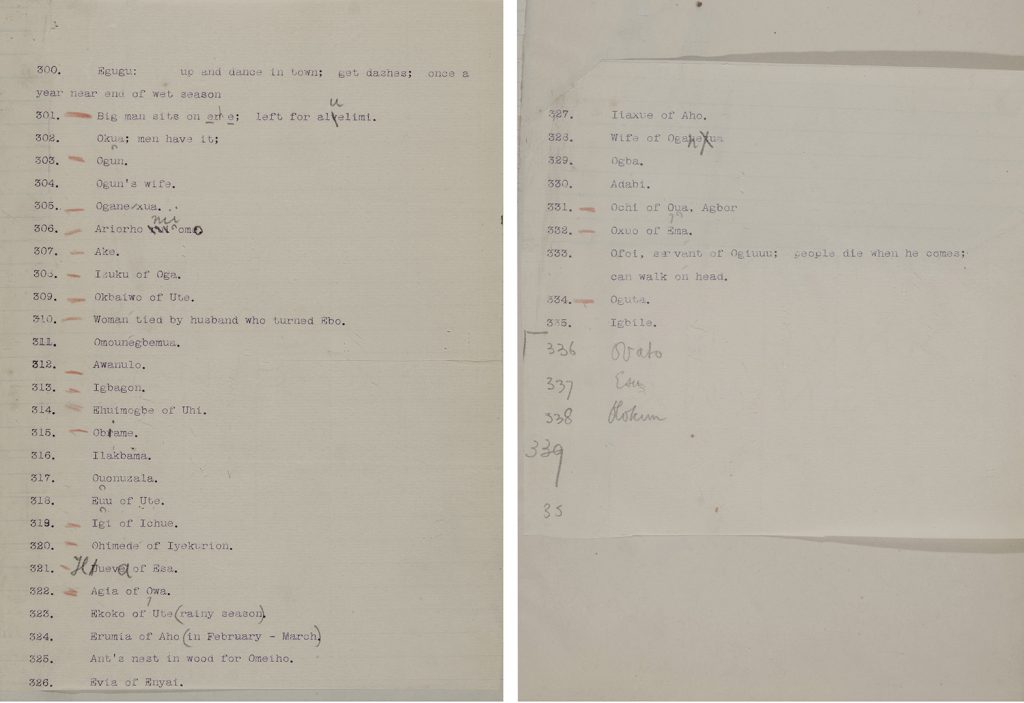

Whereas Read saw little value or purpose in these ‘modern things made to order’, it appears that, for Thomas, this was an opportunity to assemble what he perceived as a complete set of representations of Edo deities in a traditional form. While many of these deities are associated with identifiable symbols or regalia, such as that of Ovia, Thomas may have been projecting his own assumptions about the distinct visual representation of each ebo when he commissioned them to be carved in this way. Perhaps the carvers even encouraged him in this belief! In the labels attached to each ukhurhẹ and in the corresponding catalogue of collections, each is given its name.

Carvers still produce ukhurhẹ in Benin City today, and many families still maintain traditional ancestral altars in their compounds.

As part of the [Re:]Entanglements project, we commissioned an ukhurhẹ to be made as a memorial to Northcote Thomas himself. We worked with traditional carver Felix Ekhator, who has a workshop on Sokponba Road, Benin City, just opposite the famous Igun Street. Felix’s first calling was as a professional wrestler, but in the late 1970s he followed in his father’s footsteps and focused on woodworking as a career. He made our ukhurhẹ in the traditional way from the wood of a kola tree, which is hard and durable. At its top Felix carved the figure of Northcote Thomas, copying his posture and clothing from a photograph taken on his 1909-10 tour.

The finished ukhurhẹ is on display alongside a selection of those commissioned by Thomas 110 years previously in Benin City at the [Re:]Entanglements exhibition at the University of Cambridge Museum of Archaeology & Anthropology (June 2021 to April 2022). The exhibition uses contemporary artworks, such as Felix Ekhator’s ukhurhẹ, as interventions to disrupt conventional expectations of what an ‘ethnographic’ or ‘historical’ display should be, and provoke further questions. Should, for example, we honour Northcote Thomas, the colonial-era anthropologist, as an ancestor? Should we introduce his presence, his agency, alongside the cultural artefacts that he caused to be produced?

![Ukhurhe installation at the [Re:]Entanglements exhibition](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Re-Entanglements_exhibition_Ukhurhe_installation_re-entanglements.net_-1024x576.jpg)

![Ukhurhe installation at the [Re:]Entanglements exhibition](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Re-Entanglements_exhibition_Ukhurhe_installation_2_re-entanglements.net_-1024x683.jpg)

We gratefully acknowledge a small grant from the Crowther-Beynon Fund that enabled us to commission the new ukhurhẹ from Felix Ekhator.