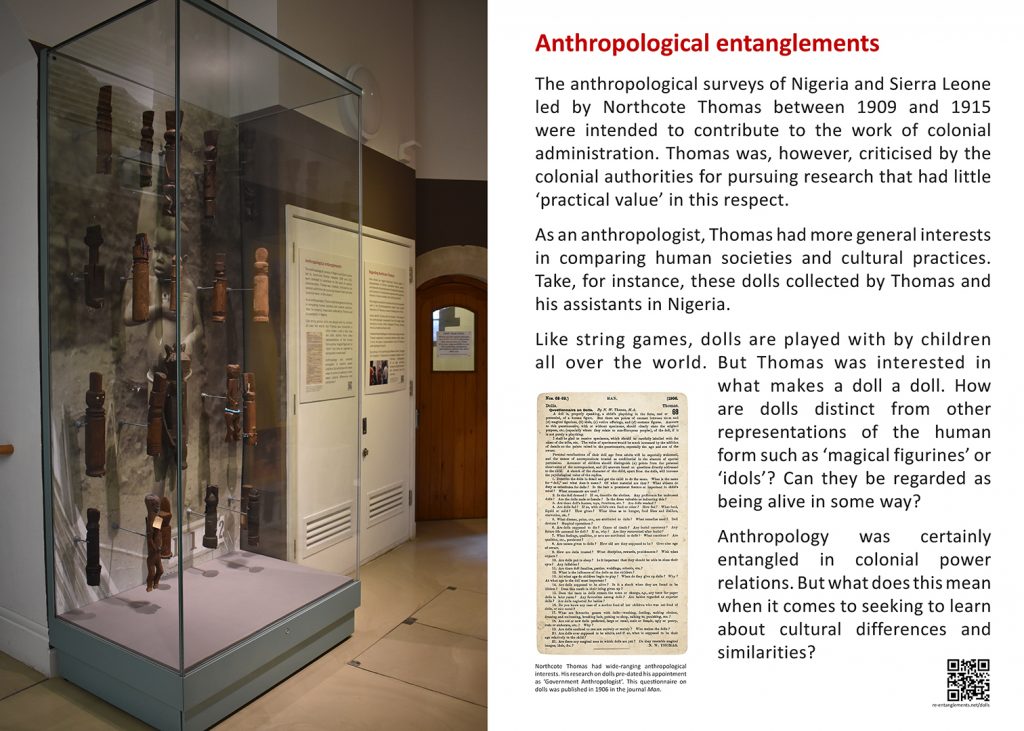

According to the Encyclopedia of Children and Childhood, dolls are known in all cultures across the world and are one of the oldest and most widespread forms of toys. Given their ubiquity, dolls made the perfect subject for comparative study across different cultural groups. Despite this, anthropological studies of dolls are rare. The colonial anthropologist Northcote Thomas collected many examples of dolls during his 1909-10 anthropological survey of the Edo-speaking people of Nigeria. Thomas’s interest in dolls pre-dated his appointment as Government Anthropologist in West Africa.

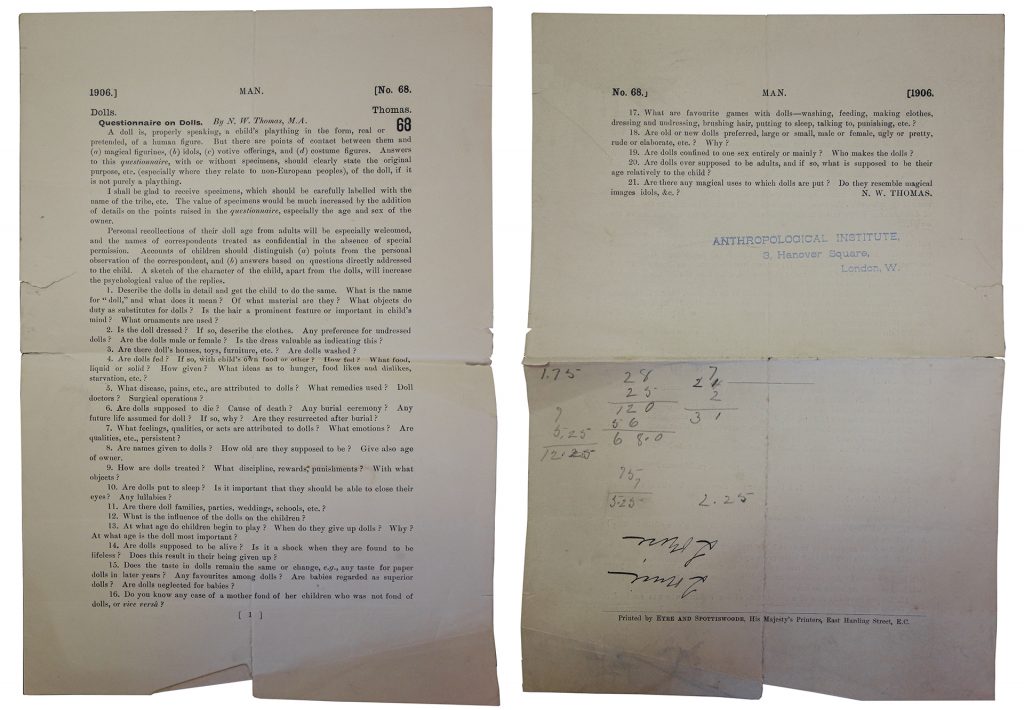

In 1906, Thomas published a questionnaire on dolls in the anthropological journal Man. The use of questionnaires distributed to colonial administrators, missionaries and other travellers was a common anthropological practice of the late 19th and early 20th century. At this time, anthropologists relied on material collected by others to inform their research. Prior to his appointment as Government Anthropologist, Thomas had not personally undertaken fieldwork.

The questionnaire shows that Thomas was interested in what defined a doll as a doll, as distinct from other representations of human figures. ‘A doll’, he writes, ‘is, properly speaking, a child’s plaything … But there are points of contact between them and (a) magical figurines, (b) idols, (c) votive offerings, and (d) costume figures’. It is clear from the questions that, even as ‘a child’s plaything’, dolls have quite remarkable properties. Many of the questions seek to interrogate in what ways dolls may be perceived to be alive, and treated as such. For instance, there are questions about feeding dolls, whether they suffer from illnesses, whether they have feelings and emotions. Do they sleep? Do they die? If so, are burial ceremonies performed?

Although Thomas was particularly interested in the use of dolls among ‘non-European peoples’, many of his queries draw upon an earlier questionnaire formulated by the American psychologist G. Stanley Hall, which was distributed to school children in the USA and Scotland. The findings of this and a subsequent study by A. Caswell Ellis were presented in an article entitled ‘A Study of Dolls’ published in 1896 in The Pedagogical Seminary. This is still regarded as a foundational work in ‘doll studies’. Thomas’s innovation was in extending this area of research into a cross-cultural, ethnographic context.

Unlike Hall and Ellis, however, it seems that Thomas did not complete his study or publish material gathered from the questionnaire. He did, however, present a preliminary paper on the subject of dolls at a meeting of the Royal Anthropological Institute on May 14th, 1907.

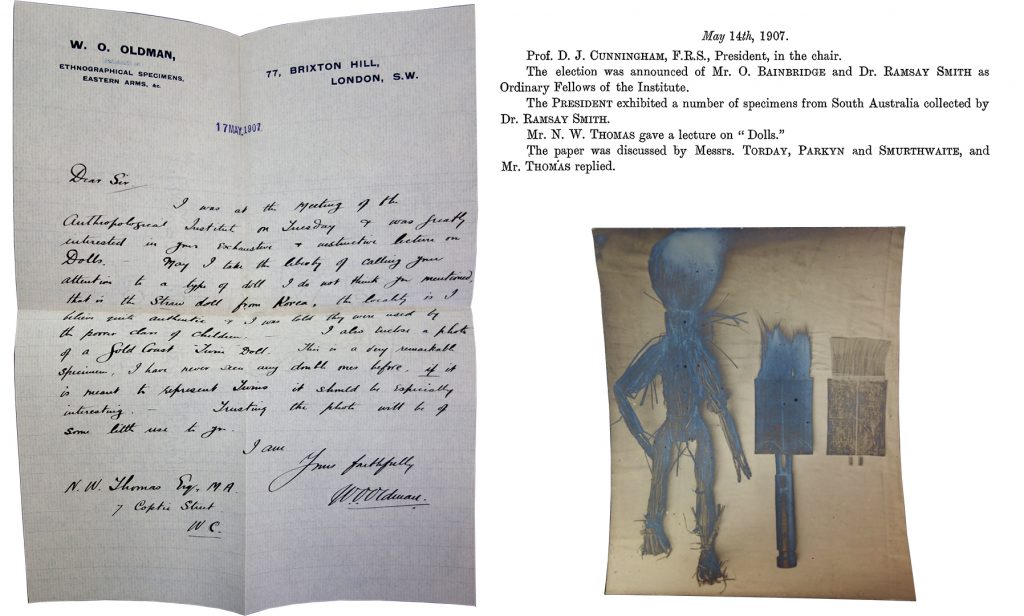

A brief write-up in the Proceedings of the Institute notes that the discussants included anthropologists Emil Torday, Thomas E. Smurthwaite and Ernest A. Parkyn. The well-known dealer in ‘ethnographic specimens’, William O. Oldman, was evidently also present. A letter survives in which Oldman compliments Thomas on his ‘exhaustive and instructive lecture’, and draws Thomas’s attention to ‘a type of doll I do not think you mentioned’: straw dolls of Korea. Oldman encloses a photograph of such a straw doll in his collection as well as a ‘twin doll’ from Gold Coast (Ghana). Perhaps Oldman hoped Thomas would be interested in buying them! (Thomas states in the questionnaire that he would be ‘glad to receive specimens, which should be carefully labelled with the name of the tribe, etc.’)

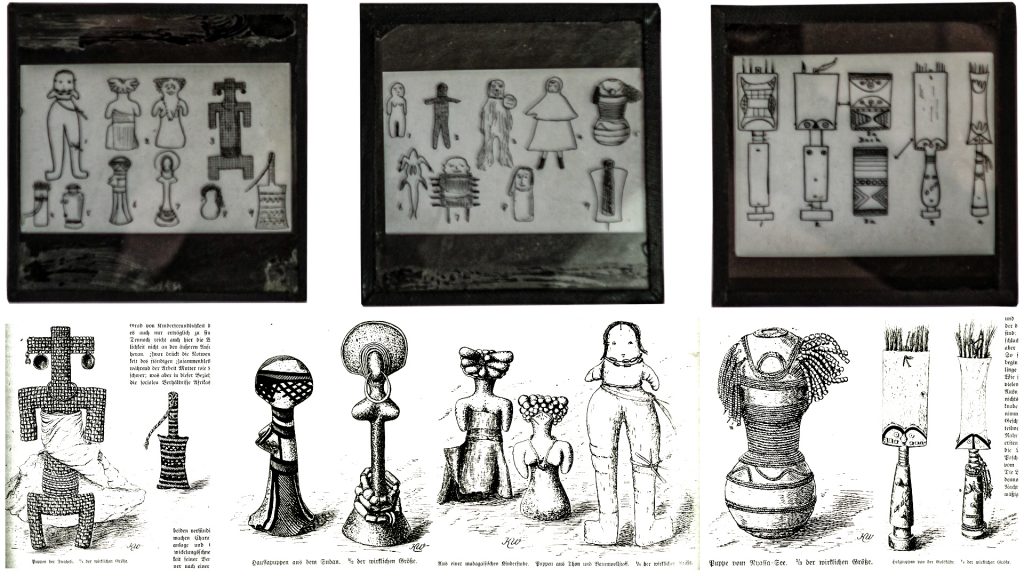

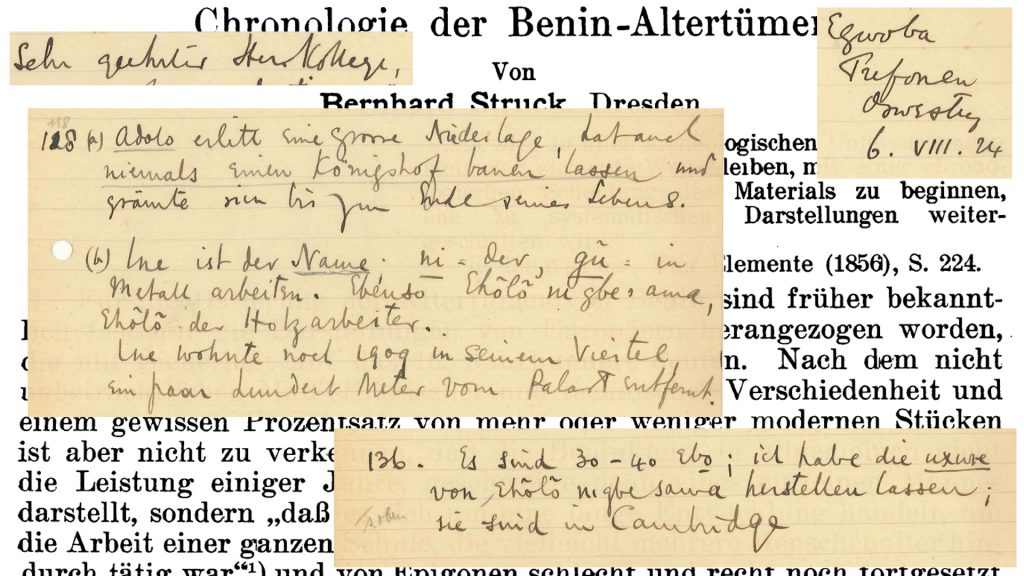

In addition to the questionnaire, Thomas had been conducting library and museum based research on dolls. Notebooks and record cards survive in the Cambridge University Library, which include sketches and notes on different examples in European collections. A number of lantern slides also survive with line drawings of dolls from the African continent. These are probably the very slides used to illustrate Thomas’s talk at the Royal Anthropological Institute in 1907. The original source for many of the line drawings is an article entitled ‘Aus dem afrikanischen Kinderleben’ (‘From the African child’s life’) by Karl Weule, assistant director at the Museum für Völkerkunde zu Leipzig, published in Westermann’s Jahrbuch der Illustrierte Deutschen Monatschefte in 1899.

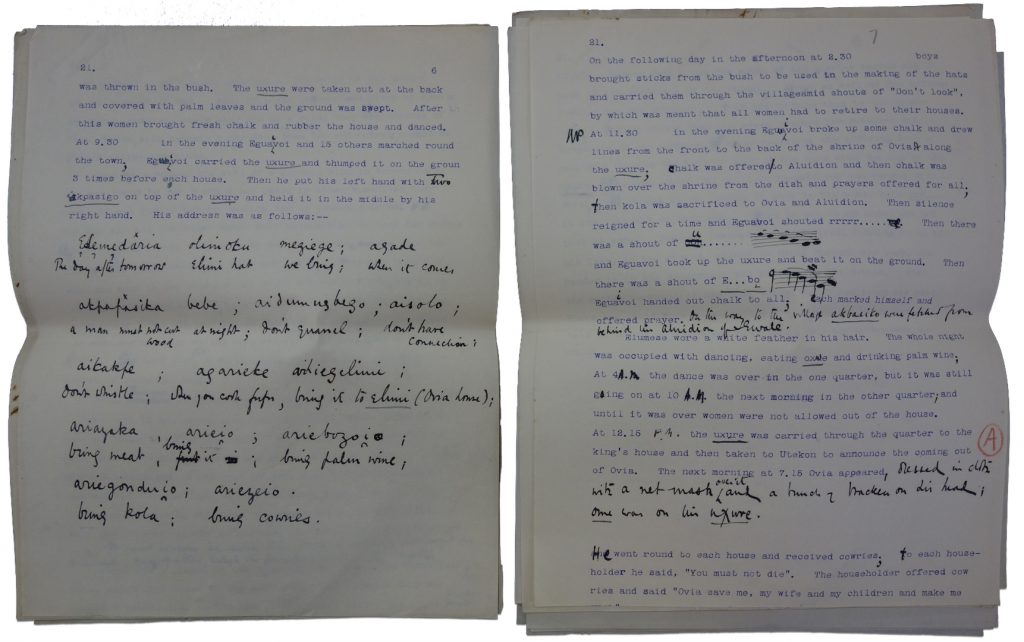

While Thomas did not publish a substantive article on dolls, he was clearly still interested in the topic at the time of his 1909-10 survey in Southern Nigeria. During this tour he collected approximately 40 dolls, mainly in the northern Edo towns of Uzebba, Otuo, Sabongida, Agbede, Irrua and Fugar. Those collected in Agbede, in particular, share many formal characteristics, and some appear to have been produced by the same maker.

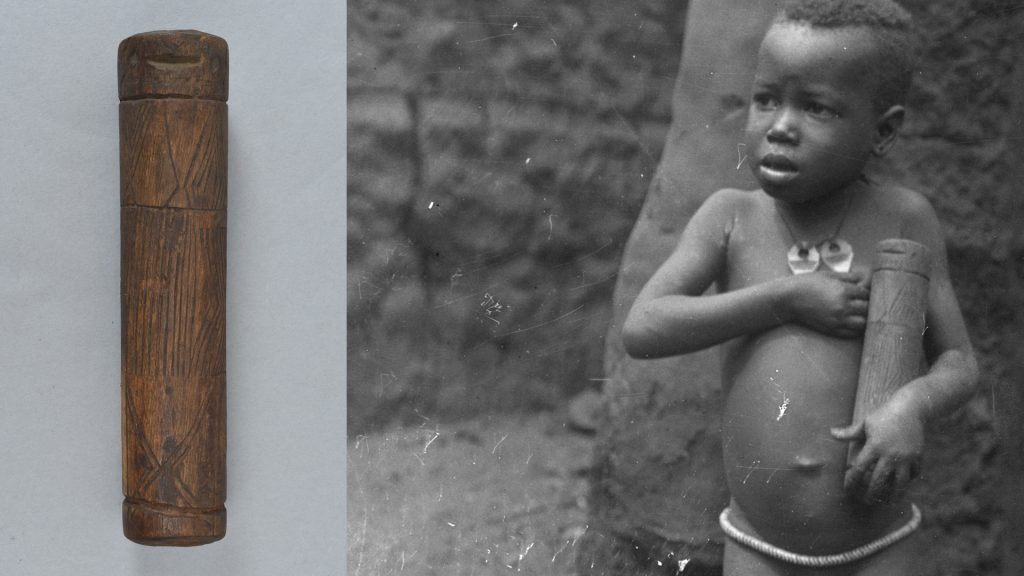

Thomas also took a number of photographs of children holding dolls. In one instance, a girl appears to be holding one of the dolls collected by Thomas. This is somewhat puzzling since Thomas records the doll in question as being acquired in Fugar, while the photograph was taken in Ikpe, on the outskirts of Auchi, which Thomas visited after Fugar. It is possible that Thomas set up the photograph, getting the girl to pose with a doll he had previously collected. Alternatively, he may have recorded the provenance of the doll incorrectly, acquiring it in Ikpe. This raises the broader question about how Thomas acquired the dolls. Did he obtain them directly from makers? Or was he purchasing them from households? If the latter, did he persuade parents to sell him their child’s doll? It seems especially cruel to think that he may have forced children to part with their beloved toys.

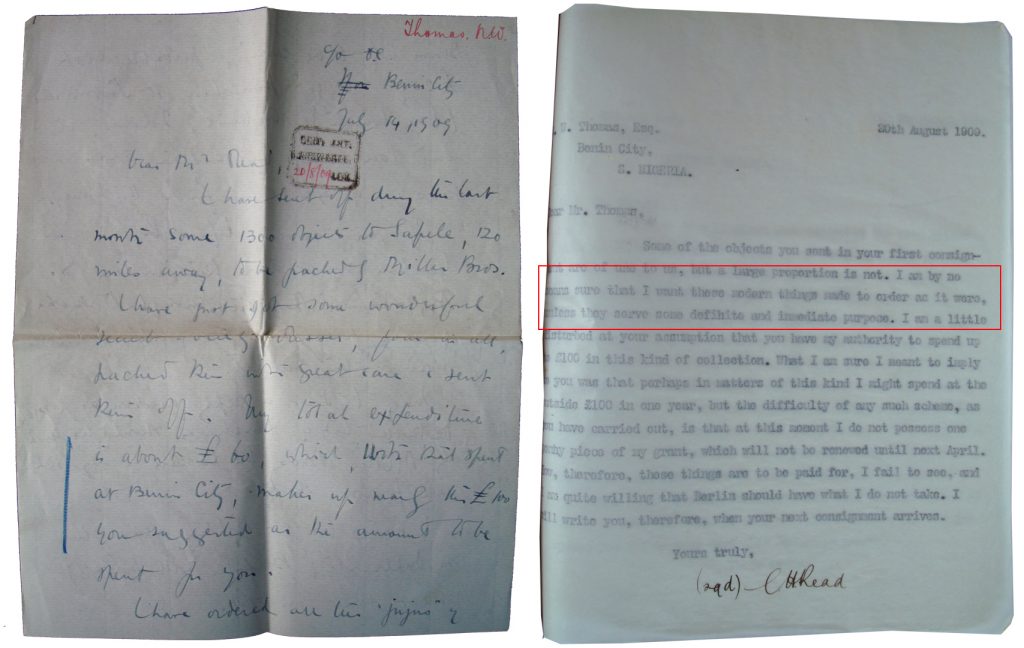

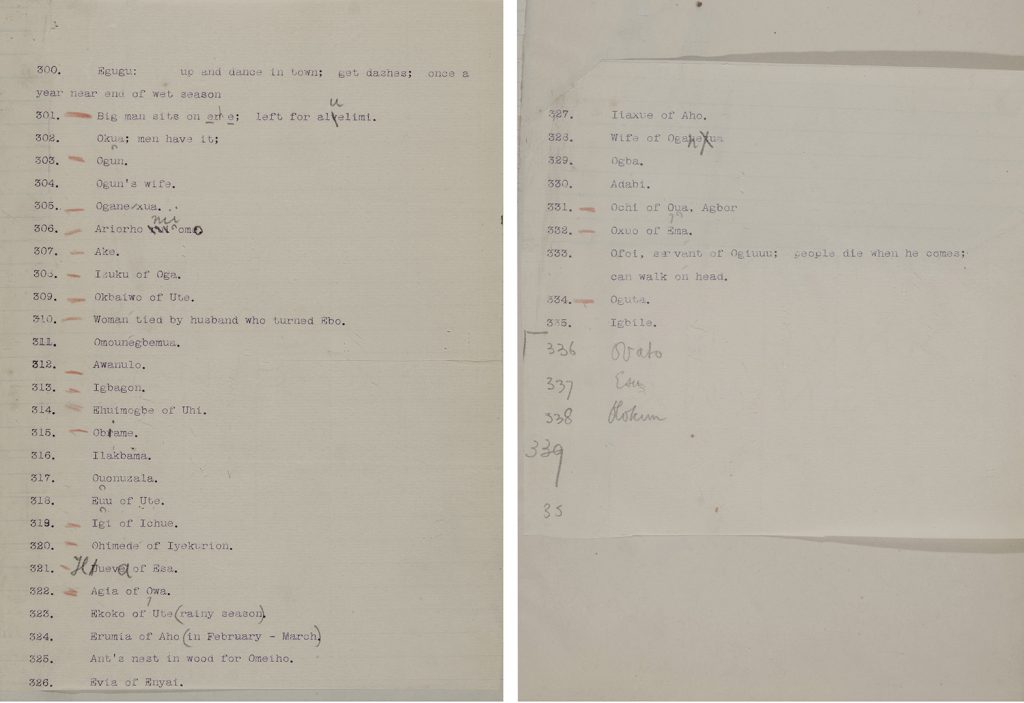

Despite assembling this remarkable collection of Nigerian dolls, Thomas did not include any discussion of them in his Anthropological Report on the Edo-speaking Peoples of Nigeria. This is not surprising since the reports were primarily intended to provide information of use to colonial administrators, and the study of dolls would have been regarded as a matter of purely academic interest. But neither have we been able to locate any unpublished fieldnotes relating to the dolls. It appears, therefore, that Thomas did not use the opportunity of his fieldwork to gather the kinds of information that he requested in his 1906 questionnaire. As with much of the material assembled during Thomas’s anthropological surveys, we have only fragmentary knowledge.

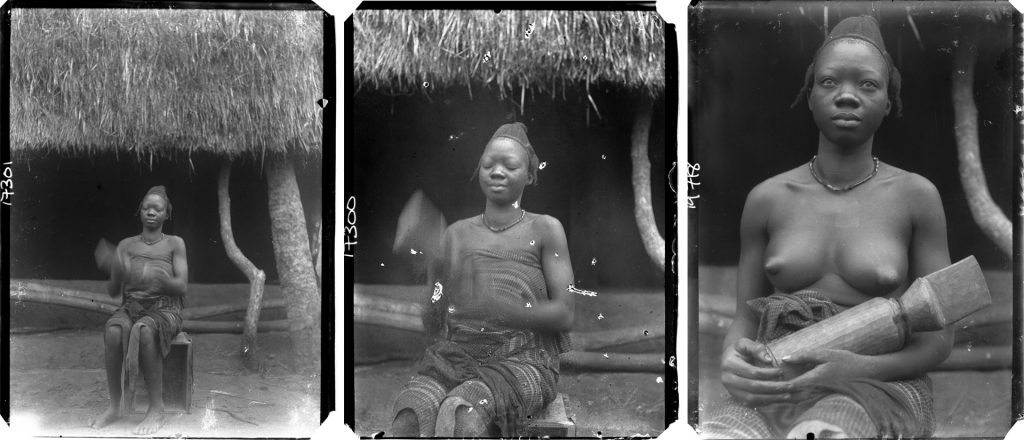

We can, however, learn much by examining the collections and photographs themselves. The form of many of the dolls is highly abstract – some are barely more than sticks. Others, even though they may not have representations of arms or legs, have facial or body scarification marks similar to those worn by local people. Most striking is the correlation between the body ornamentation of the dolls and children photographed by Thomas, including hair beads, necklaces, waist bands and anklets. Some of the dolls are more representational in style, with arms, legs and more realistically carved facial features.

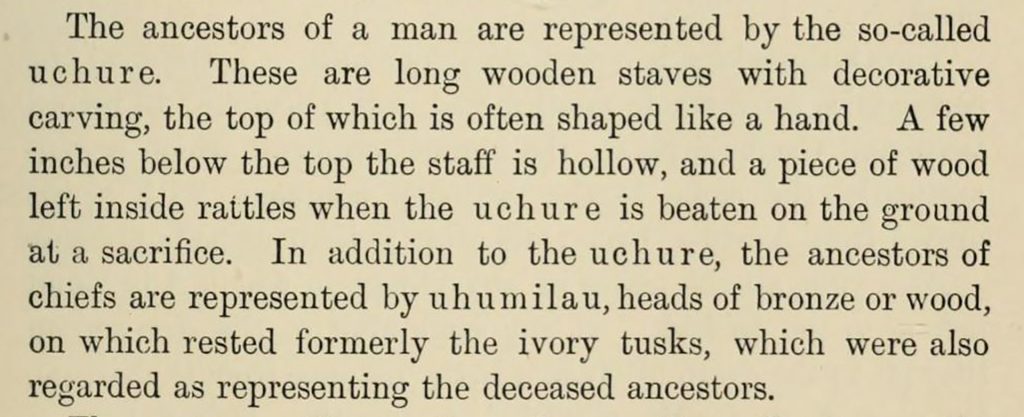

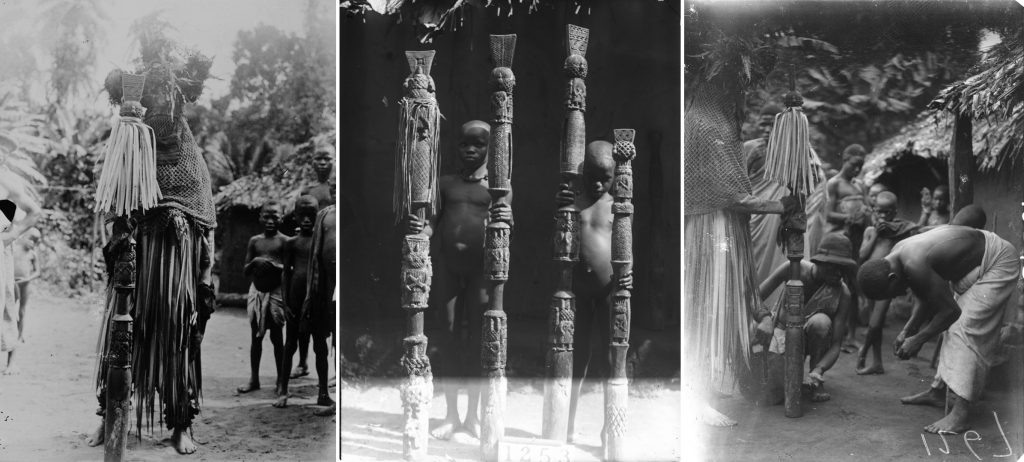

In most cases Thomas uses the English word ‘doll’ to label these figures. Occasionally a local language word is used. Two of the dolls collected in Fugar are, for example, labelled ‘omo’, which means child in the Edo language. One of the dolls collected in Agbede is labelled ‘utomo’, while another collected in Uzebba is labelled ‘omowowo’ (both of these include the word fragment ‘omo’). One example collected in Irrua is labelled ‘agagaigboie’.

In the absence of more detailed contextual information, it is not always clear what distinguishes the figures Thomas labelled as dolls from other kinds of figures collected by Thomas. Some, particularly more representational and less abstract figures, are visually more of less indistinguishable from those Thomas labels as ‘ele’ or ‘olose’ figurines, or figures associated with shrines. Fascinating though this wonderful assemblage of Nigerian dolls is, we can only regret that Thomas did not also collect the kinds of information he sought to elicit from others in his 1906 ‘Questionnaire on Dolls’. How interesting it would have been to have answers to those questions: Were they fed? Did they suffer from illnesses? Do they die? Are they reincarnated? What names did they carry? Did they feel emotions? Who made them? Do they have magical properties? We shall perhaps never know.

![Ukhurhe installation at the [Re:]Entanglements exhibition](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Re-Entanglements_exhibition_Ukhurhe_installation_re-entanglements.net_-1024x576.jpg)

![Ukhurhe installation at the [Re:]Entanglements exhibition](https://re-entanglements.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Re-Entanglements_exhibition_Ukhurhe_installation_2_re-entanglements.net_-1024x683.jpg)