One consequence of the [Re:]Entanglements project is that the various archives and collections assembled by Northcote Thomas during his anthropological surveys in Nigeria and Sierra Leone are gaining greater exposure. This is true in West Africa, but also in the UK and elsewhere. As a example, two objects collected by Thomas are currently being featured in an exhibition at Kettle’s Yard Gallery in Cambridge entitled ‘Artist: Unknown, Art and Artefacts from the University of Cambridge Museums and Collections’. The exhibition opened on 9 July 2019 and will run until 22 September 2019.

The exhibition brings together a selection of artworks and artefacts from across the University of Cambridge’s diverse collections, including the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology (which holds the Northcote Thomas collections), Cambridge Botanic Garden, Museum of Classical Archaeology, The Fitzwilliam Museum, The Polar Museum, Sedgwick Museum of Earth Sciences, Whipple Museum of the History of Science, Museum of Zoology, University Library and a couple of the colleges. The selected items share one thing in common: despite displaying remarkable creativity and skill, the identities of the artists or makers are not known. As an exhibition text states, ‘Not knowing, in each instance, who the artist or maker is, shifts our attention from a name and a known or imagined persona, to focus instead on the multiple reasons why the creator is lost to history’.

In the context of historical ethnographic collections, of course, the absence of a named individual artist or maker is the norm, rather than the exception. We’ll return to this issue, but first let us take a look at the two artworks/artefacts collected by Thomas that feature in the exhibition.

Z 14207: Lamellophone (ibweze)

According to Thomas’s label, this lamellophone or thumb piano was collected in 1911 in Enugu-ukwu, south-west of Awka, in present-day Anambra State, Nigeria. It is one of a number of lamellophones collected by Thomas. The Igbo word for a lamellophone is ubọ-aka, and it is thus curious why Thomas gives this particular instrument the name ibweze. According to Dr Ikenna Onwuegbuna, a lecturer in the Music Department at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka, and native of Awka, ibweze – which should actually be spelt ibhe-eze – means simply ‘the thing belonging to the king’, or ‘the king’s thing’, and is not the name of an instrument at all. Onwuegbuna speculates that this ubo-aka was made for the Eze (king) or a musician in his court.

Judging from the lamellophones collected by Thomas, they were a medium for displaying the virtuosity of those who made them as well as the musicians who played them. However, the ibweze is particularly remarkable given the elaborate superstructure (indeed, a lamellophone fit for a king!). The finger-board, which has six cane tongues, is mounted onto a wooden block. Above the finger-board, this has been carved with two human faces, one facing front, one facing back, as well as two antelope heads facing left and right. Surmounted on the antelopes’ horns is a cat-like creature – probably a leopard given its spots. The leopard is also a symbol of kingship.

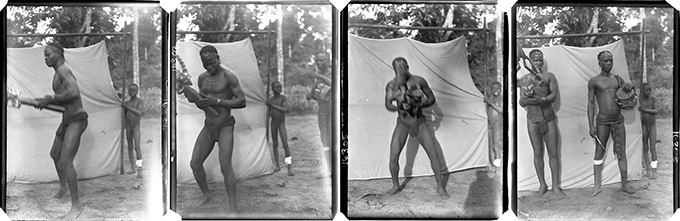

The elaborate carving makes the instrument heavy and poorly balanced. One would imagine that it is impossible to play, but Thomas also took a series of photographs of the ibweze being played along with a drum, which Thomas also acquired. In his register book, Thomas describes the photograph series simply as ‘Young men’s dance’. A further photograph shows both the thumb piano and the drum (Z 14200) lined up before a backcloth with other objects that he had collected in Enugu-ukwu.

We know that Thomas purchased objects for his collections and he also commissioned artists and craftspeople to make things for him. We do not know, however, whether the ibweze was a specially commissioned piece. If it was, we might speculate that the ibweze-maker used the opportunity to show off his skills as an artist, perhaps aware that his work would travel to a distant land, carrying his reputation and fame with it. Did he imagine that 108 years later, his masterpiece would be displayed in a fine art gallery in Cambridge?! If Thomas did commission the ibweze, it is possible that he was aware of the artist’s name – what a shame that he appears not to have recorded it.

Z 25889: Carved and painted wooden head

The second object from the Thomas collections featuring in the ‘Artist: Unknown’ exhibition is much more enigmatic. The label is of a kind that was attached to Thomas’s collections when they were originally accessioned at the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology. It reads simply ‘Head, one side painted white, the other with white spots, straw round neck’. There is no surviving record of where it was collected or what its original purpose or function was, let alone who created it.

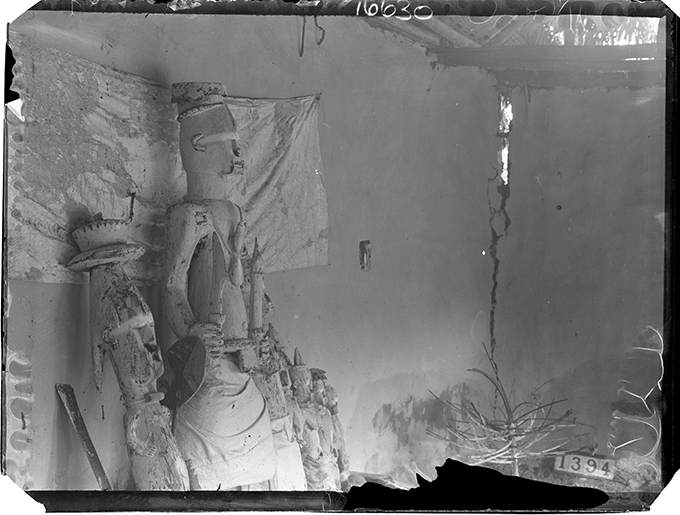

Unlike the ibweze, Thomas took no photographs showing the carving in situ prior to being collected. There are, however, some formal similarities with some shrine figures photographed by Thomas in December 1909 in Aja-Eyube (spelled Ajeyube by Thomas), which is now a suburb of Agbarho in Delta State, Nigeria. This is, however, inconclusive.

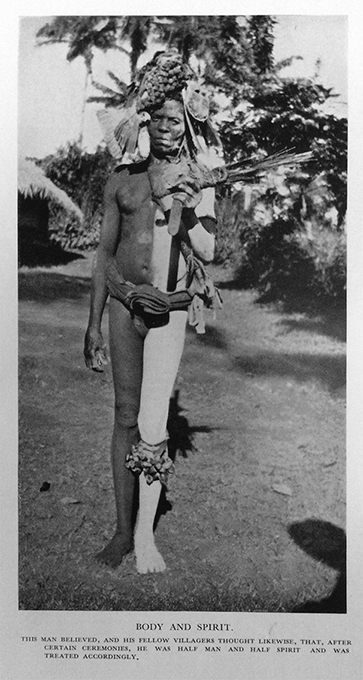

The division of the body using paint – in this case white on the right side, and spotted on the left – has cosmological significance and is found on both carved figures and human bodies. The Anglican missionary, George Basden, published a photograph of a man with his left side painted white in his book Niger Ibos [sic] (1938), which he stated represented the dualism of ‘body’ and ‘spirit’.

More than many of the objects that Thomas collected, this carved wooden head perhaps most closely resembles an ‘art object’, the primary function of which is aesthetic.

Artists unknown

In a podcast accompanying the ‘Artist: Unknown’ exhibition, Director of the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Nicholas Thomas (no relation to Northcote!) reflects on historical distinctions between art museums and ethnographic museums. In the following excerpt he discusses a Fijian painted barkcloth from the Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology that also appears in the ‘Artist: Unknown’ exhibition, but the broader points apply equally to the Nigerian objects.

Whereas (Western) art objects are often valued because of their association with individual artists, (non-Western) ethnographic objects were historically valued as ‘specimens’ of the material culture of particular societies and cultural groups. Although they recognized and appreciated the skills and artistry of individual makers, anthropological collectors such as Northcote Thomas were primarily interested in what material culture could tell them about a given ‘people’. Thus, Thomas conceptualised his collections in terms of ‘technologies’, or their function in relation to religion and ritual. He was also interested in documenting ‘decorative arts’, both in architecture and artefacts. This was, however, principally of interest insofar as distinctive styles and techniques were perceived to delineate cultural boundaries and influences. Thomas used art(efacts) much as he used language and physical type photography as a tool in cultural mapping.

It was only in the 1980s that the distinction between art objects and ethnographic objects began to be questioned critically. This period also saw the rebranding of many ethnographic collections as ‘World Art’. Today, acknowledging the individuality of the artists and craftspeople responsible for making these works is part of a decolonisation agenda. The reduction of singular works such as the ibweze or carved head collected by Thomas to representative specimens, with the corresponding erasure of the identities of their individual makers, is part of the epistemic violence of colonialism. But, at the same time, we might also question whether the highly-commoditised global art system, with its obsession with the named celebrity artist, represents another form of coloniality, obscuring other possible artworlds in which creativity is not necessarily the property and outcome of individual activity.