Although there were many early experiments with colour photography from the 1850s, it was not until the mid-1930s, with the introduction of Kodachrome film, that it became widely used. All of Northcote Thomas’s photographs made during his anthropological surveys of Southern Nigeria and Sierra Leone between 1909 and 1915 were monochrome. Since the beginning of photography, however, various techniques have been used to hand-colour monochrome prints. Hand-colouring photographic prints using a fine brush with different kinds of dyes, watercolours and oils was a highly-skilled task. Demand for hand-coloured photographs reached its peak in the early twentieth century.

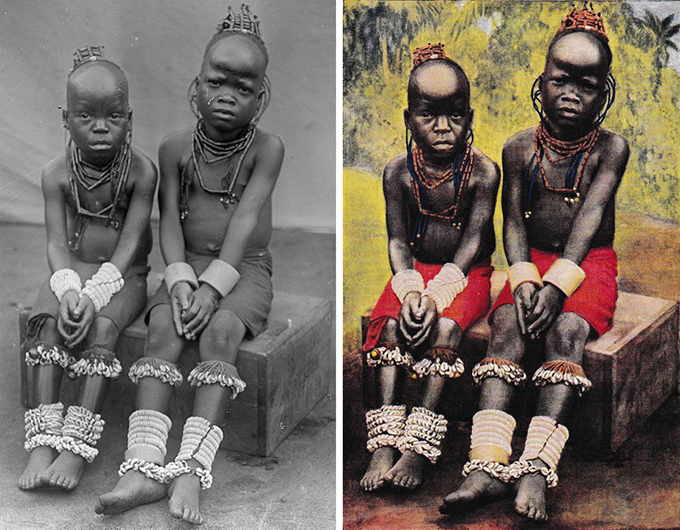

To date, we have come across only one historical example of a photograph taken by Thomas that has been hand-coloured. This was published in the serialised pictorial encyclopaedia, Peoples of All Nations, around 1920. In the section entitled ‘British Empire in Africa’ Thomas contributed around 23 photographs, many of which have been touched-up for publication, among these is the colour plate disparagingly entitled ‘Gewgaws of Primitive Society’. The photograph shows two young girls, which Thomas elsewhere describes as ‘onye ebuci’, adorned with bracelets of hippo ivory, anklets and garters of cowries, and necklaces and headdresses of long red beads. In addition to colouring the photograph, a vaguely ‘tropical’ background has been painted in place of Thomas’s calico photographic backdrop.

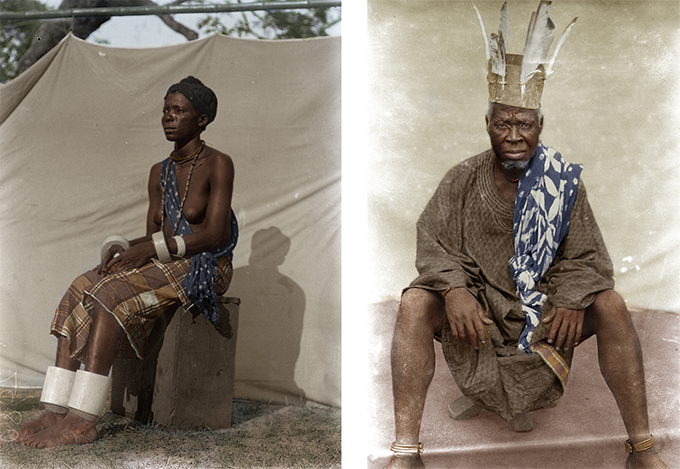

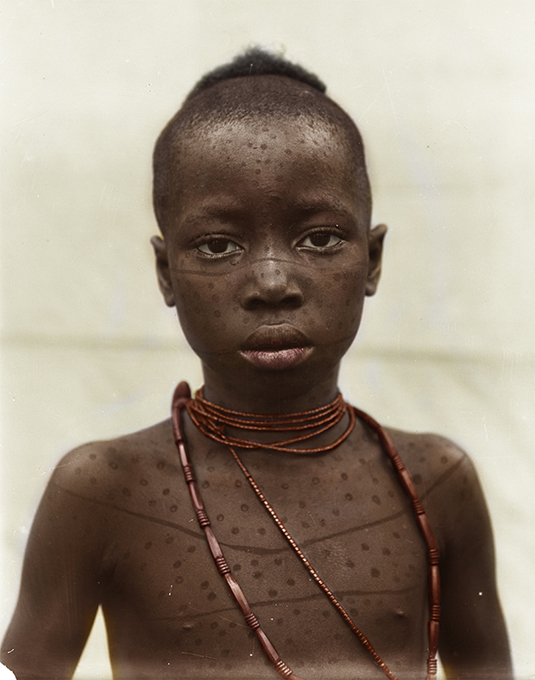

Today, with digital tools such as Adobe Photoshop, new possibilities for colourising historical monochrome photographs present themselves, though the process is no less skilled. Artist and Ukpuru blogger, Chiadikōbi Nwaubani has long been interested in historical visual representations of Nigeria and has been digitally colourising some of the Northcote Thomas photographic archive.

Chiadikōbi explains:

I’ve started colouring some of the photographs from the Northcote collection and I’m focusing mainly on the photos of his tours of the Igbo area. Since the colouring is partly based on guess work, some knowledge about the culture helps in deciding what is coloured what, such as the indigo cloth in the picture of the Eze Nri. Resist-dyed indigo cloth like that is still popularly used and I could notice the depth of the grey and the patterns and guess that it was one of the indigo cloths.

I started colouring some of these pictures a few years ago from digital scans of the printed Anthropological Report volumes. I was looking at other areas of the past, and at the time I used the Northcote Thomas images to practice colouring photos. I think the impact of the original black and white photos was less than these coloured versions because of the quality, but there was another sense of familiarity that was added to the pictures after they were coloured, partly because the age and the surroundings had already made the images quite distant.

One of the reactions to Northcote’s pictures I’ve heard is that ‘they don’t look like Igbo people’ (by some Igbo people referring to the pictures he took of Igbo people), and I think this was partly because of the lack of reference for anything in the pictures that they can relate to today, which may also be related to the ambiguity that black and white gives some objects, in this case cultural ones. The colourisation adds another sense of life to the photos, which also includes the colouring of material culture.

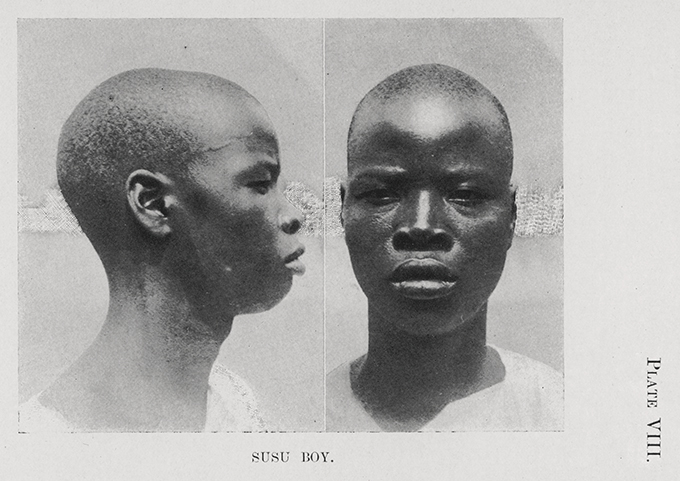

See Chiadikōbi Nwaubani’s [Re:]Entanglements project blog on his ‘Susu Boy’ painting.