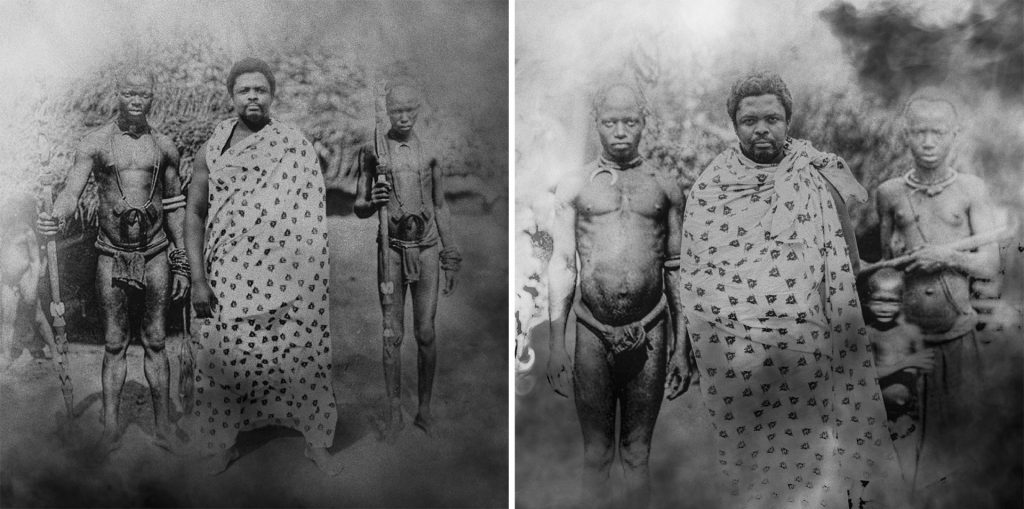

Inspired by Northcote Thomas’s archival images, the Nigerian photographer Nnaemezie Asogwa has created a powerful photo series entitled Mourning Clothes that commemorates the anti-colonial Ekumeku movement. Ekumeku was an underground resistance movement, which sought to thwart British incursions into Anioma (Western Igboland) between 1883 and 1914. As documented by the historian Don Ohadike in his book The Ekumeku Movement, there was a succession of waves of Ekumeku activity over this thirty-year period. Ekumeku operated covertly, employing local knowledge of the forest environment to launch ambushes on its targets. Colonial forces retaliated disproportionately, destroying towns and communities thought to be associated with the movement.

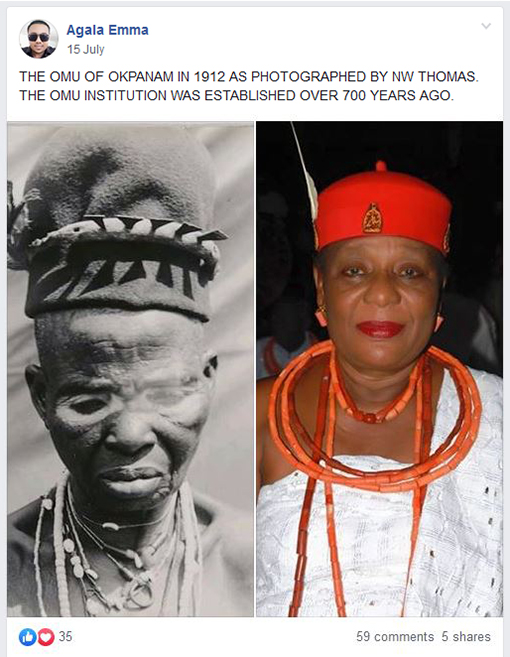

Anioma was the focus of Northcote Thomas’s third anthropological survey, which took place between July 1912 and August 1913. Thomas’s itinerary included many towns in the Asaba hinterland that directly experienced the impact of the Ekumeku Movement, including Ogwashi-Ukwu, Onicha-Olona, Ubulu-Ukwu, Ukwunzu, Igbuzo, Idumuje-Ugboko, Ezi and Issele-Azagba. Despite the recentness of these events – Ogwashi-Ukwu, for instance, was the main locus of hostilities in the 1909-10 wave of Ekumeku – there is seemingly little overt trace of conflict in Thomas’s photographs. Indeed, one of the reasons why Asogwa thought it important to work on Ekumeku was the apparent absence of a visual record of the war, as well as its absence from national narratives and educational curricula in Nigeria today.

In this article, Nnaemezie Asogwa tells us more about the ideas behind the project, his use of Northcote Thomas’s photographs, and his reflections on the memory of colonial violence that continues to ‘live under the skin’.

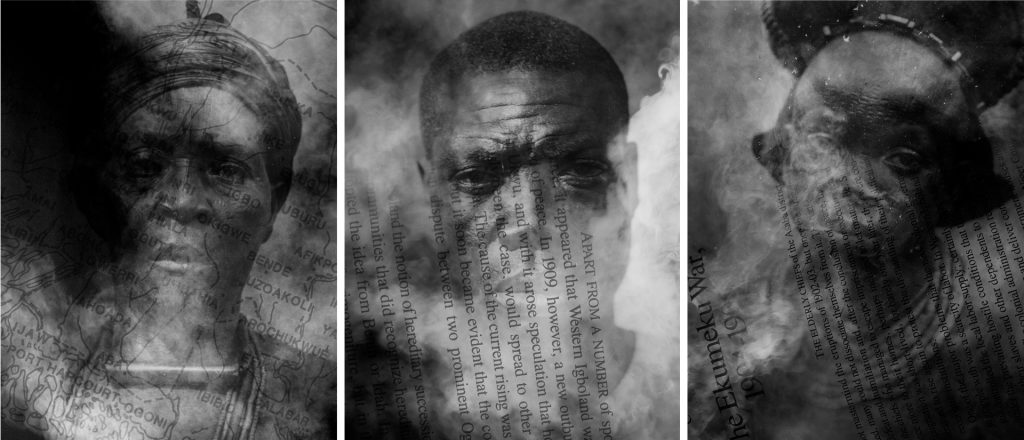

Among the violences of colonialism was the destruction of traditional ways of transmitting knowledge of the past. In my recent practice as a photographer, I have been interested in exploring how the photographic image can open up other ways of thinking about the past. My work seeks to draw attention to what has been forgotten, what is being systematically erased, and what needs to be remembered.

The Ekumeku war was an anti-colonial struggle that took place in South-eastern Nigeria, where I come from. Yet Ekumeku was never mentioned during my formal education in Nigeria. It is absent in our school history books and our cultural institutions. In my research on the conflict so far, I have been unable to find any photographs documenting it.

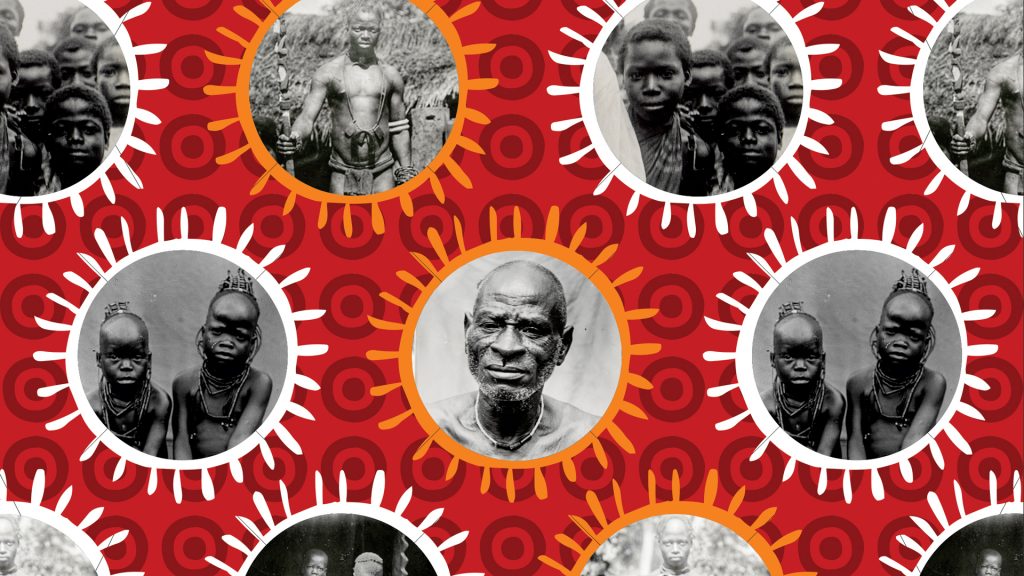

Mourning Clothes calls to mind not only those unnumbered and unnamed people who were killed while resisting the colonial invasion of their land, but also the loss of the memory of that war. When someone dies in my community, the family goes to the market and buys cloth – it might be plain white, or a printed Ankara cloth; wealthy families might even have a cloth designed for them. This is often distributed to members of the family, who will wear mourning garments made from the cloth for an agreed period, usually a year. The wearing of the clothes binds the bereaved together with each other, with the memory of their shared loss, and with the family home, no matter how far away that may be.

My idea, then, was to design a mourning cloth that would carry the memory of the Ekumeku war, and to photograph people wearing the cloth in different locations over a year. I developed the project while studying for an MA in Photography in the UK and I wanted to presence this forgotten war in the English landscape. There is another tradition in Igboland: if someone is killed, the body of the victim will be taken to the gates of the compound of the person who has perpetrated the crime. Through photography, I wanted to lay the body of this memory – the memory of Ekumeku – here in Britain, at the gates of those responsible for the colonisation of Nigeria.

My original plan met with some challenges. Firstly, my intention had been to incorporate archive photographs documenting the Ekumeku conflict in the design of the cloth. As already mentioned, my search for such photographs drew a blank. Secondly, my work on the project in 2020 coincided with the spread of the Covid-19 pandemic and the consequent lockdown, which made it difficult for me to access certain technical facilities and also to work with models in different locations. While these circumstances imposed restrictions, I believe they also provided opportunities.

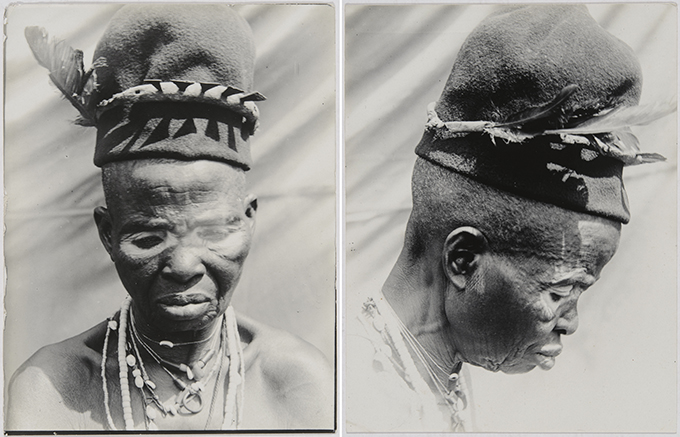

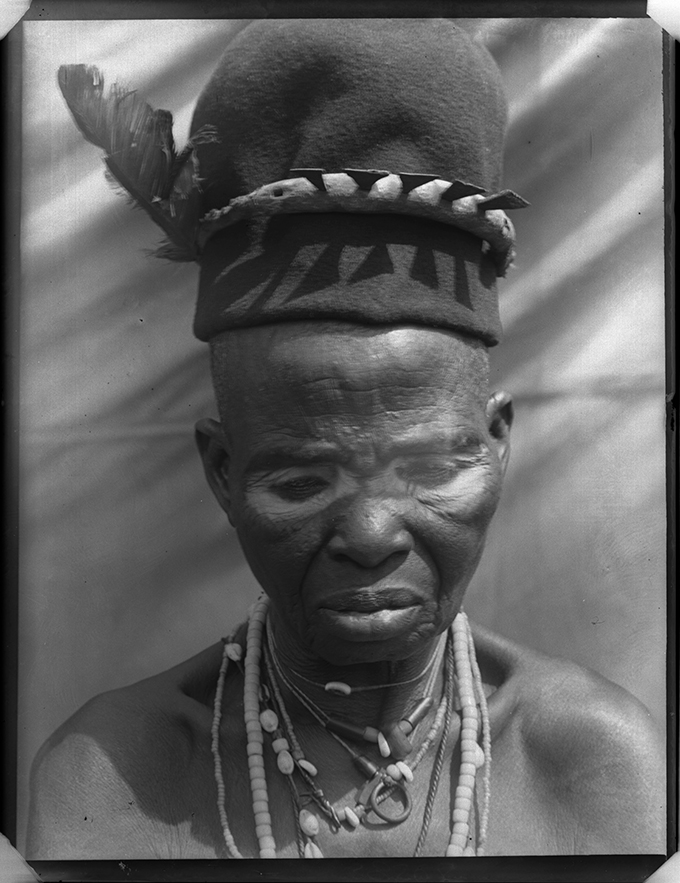

The lack of historical images documenting Ekumeku led to my working with Northcote Thomas’s photographs. I was engaged as a photographer at the opening of the [Re:]Entanglements project exhibition at the National Museum in Lagos in 2019. The exhibition featured Kelani Abass’s artistic engagements with photograph albums from Thomas’s anthropological surveys kept at the museum. This was my first introduction to Thomas’s photographs. Later, when I started work on Mourning Clothes, I contacted the [Re:]Entanglements team and was really excited when they sent me a link to the project Flickr site, where Thomas’s photographs are organised according to location. It was then I discovered that he spent a year working in the Anioma / Western Igbo area and there were hundreds of photographs taken in locations where the Ekumeku struggle took place.

I wondered how it was possible for a colonial anthropologist to roam around taking photographs in an area that had witnessed such strong anti-colonial resistance. It caused me to reflect upon the politics of dominance that came with colonialism. Although the photographs did not show the Ekumeku war explicitly, I believe there is an indexical relationship between them and the conflict. Ekumeku was organised in secret, and I have no doubt that some of those photographed were involved; others would certainly have lost family members to the struggle. Like the Ekumeku movement itself, the conflict, though not visible on the surface, is there in the ‘underneath’ of Thomas’s photographs. This added further poignancy to the images, and these became the photographs that I incorporated into the textile design for Mourning Clothes.

Due to the pandemic restrictions I was unable to print the cloth with Thomas’s photographs, so I had to improvise with another fabric. I see Mourning Clothes as a work-in-progress. I still intend to have the mourning cloth design printed and to make more photographs, building on the initial series. Another consequence of the pandemic restrictions was my inability to work with the range of models and locations that I had initially planned. Instead, I explored photomontage techniques to a greater degree. Here I was particularly inspired by the work of the Congolese artist Sammy Baloji.

In Mourning Clothes I have tried to create a monument to those who were killed in the anti-colonial struggle. Many would have died without receiving proper rites. In my community, if someone dies without a befitting funeral, they cannot rest in peace. In Igbo, they are known as ozu akwagihi akwa (a corpse whose funeral rites have not been completed). Their souls wander restlessly, haunting unoccupied places, trees, hilltops and other places. There is no limit to how far they can travel in time and space.

Memories of Ekumeku are like ozu akwagihi akwa. Even if they are not recognised as such, their trace lives on in unexpected places: in stories, in dispositions, in the minds of people far removed from the landscapes where the events happened. Repressed memories manifest in unpredictable ways. One might wonder, for example, whether some of the anger we saw in the recent Black Lives Matter riots, in the response to the killing of George Floyd, was not in some way a resurfacing of the memory of the violence that was used to suppress Ekumeku and other similar anti-colonial movements? These things are not entirely erased, but continue to live under the skin until they are divined in some sense.

Images: Nnaemezie Asogwa

Text: Nnaemezie Asogwa and Paul Basu