In the late nineteenth century and early twentieth century, anthropologists were fascinated by the seeming ubiquity of the popular pastime of ‘string games‘ – the making of ‘string figures’ or ‘cat’s cradles’. As the pioneering British anthropologist, Alfred Cort Haddon wrote in 1906,

In Ethnology, nothing is too insignificant to receive attention … To the casual observer few amusements offer, at first sight, a less promising field for research than does the simple cat’s-cradle of our childhood; and, indeed, it is only when the comparative method is applied to it that we begin to discover that it, too, has a place in the culture history of man.

Haddon encountered the game during his 1888 visit to the islands of the Torres Straits (the channel between northern Australia and New Guinea). He observed that the Torres Strait string figures were much more elaborate than those he recalled from his childhood in England. He also noted that they were more often made by a single ‘player’, rather than two – and by no means was the game restricted to children. He collected examples of completed figures, which he subsequently donated to the British Museum.

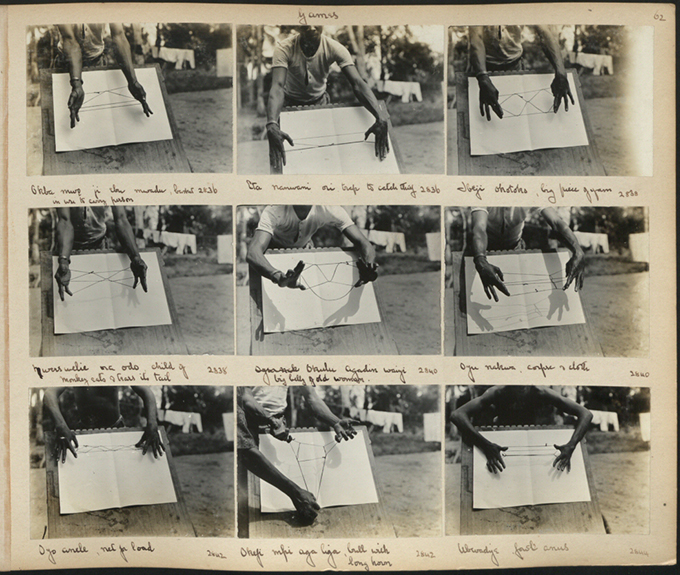

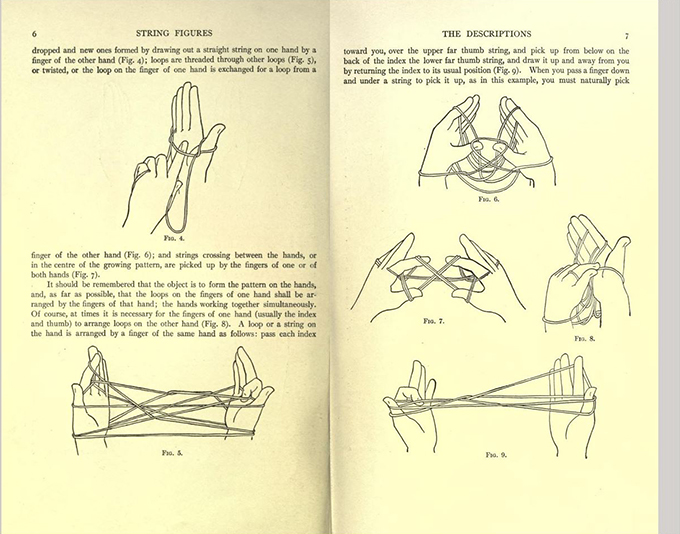

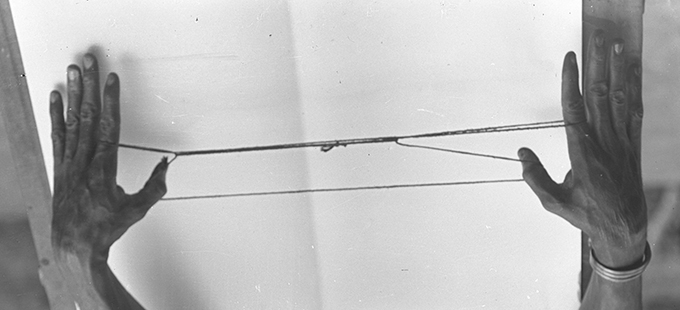

Haddon continued to document string games when he returned to the Torres Straits in 1898 as leader of the Cambridge Anthropological Expedition. With W. H. R. Rivers, he formalised a ‘method for recording string figures’ and published this in the anthropological journal Man in 1902. Rivers and Haddon stressed the need to document the various stages of making each figure, rather than merely photographing, drawing or even collecting the finished figures. They proposed a nomenclature for describing the various steps and actions involved in making string figures, and this has been adopted by many subsequent researchers.

During his 1910-11 anthropological survey in Southern Nigeria, which focused on the Igbo-speaking people of what was then Awka District (more or less present-day Anambra State), Northcote Thomas took two series of photographs of string games. He recorded ten string figures in Agukwu Nri and three in Ebenebe. These are among the earliest photographs of African string figures. Thomas did not write about string games in his reports or other publications, and no field-notes survive from this tour, so we do not know if he documented the games according to Rivers and Haddon’s methodology, or whether he simply took photographs of the finished figures.

Philip Noble, who co-founded the International String Figure Association in 1978, has made a study of Thomas’s photographs of Nigerian string figures. In an article ‘Some Nigerian String Figures’ published in the Bulletin of the International String Figure Association in 2013, Noble reconstructs the methods by which the figures were made. The article is republished, with kind permission of Philip Noble and the Bulletin’s editor, at the end of this blog. Philip Noble has also very kindly created a series of short videos for [Re:]Entanglements in which he demonstrates how each of the figures was made.

Thomas recorded the Igbo name for each of the figures. These would have been recorded in the local Igbo dialects, and Thomas’s phonetic spelling of Igbo words is idiosyncratic. In the following sections, we include Thomas’s English translation of the names, his rendering of the Igbo names, and also a translation of the names from English into standard Central Igbo, courtesy of Yvonne Mbanefo. Northcote Thomas records the Igbo word for string games generically as akpukba – Ọkpụkpa simply means ‘to make or create something by hand’. Igbo-speaking friends and correspondents have told us of other words for string games: Ikpo ubo (‘to play strings’), Gadas, Atụmankasa. Some of these may refer to particular figures rather than the game more generically. As always, we welcome any feedback on these string games and their names – please leave a comment.

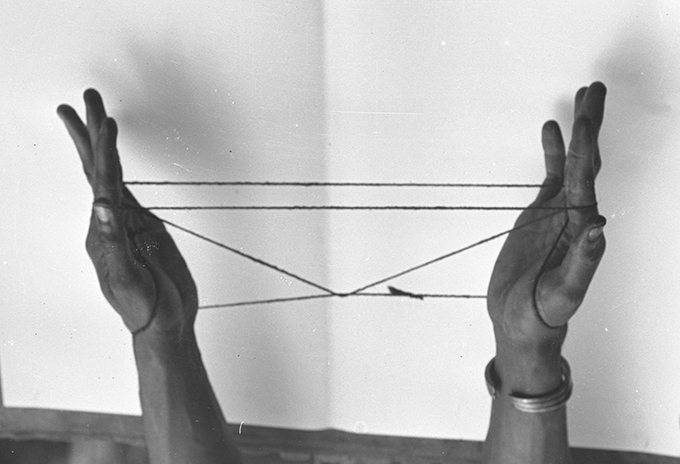

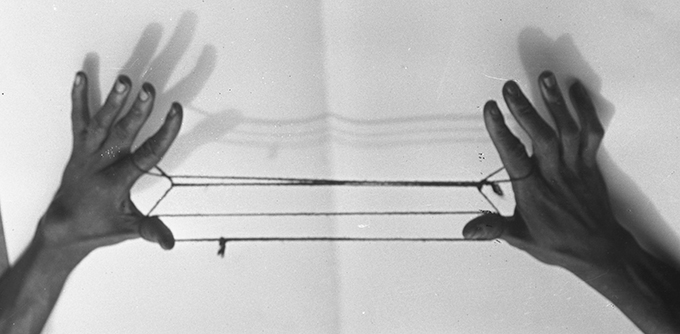

1. Trap to catch thief

N. W. Thomas: Eta nanwani ori; Central Igbo: Ọnya onye ori

Philip Noble notes: This is figure is known throughout West Africa, and often has the same name. In most locations a second player inserts a hand or finger into the lower trapezoid. When the first player releases his thumb loops and extends the figure, the second player is caught in a noose.

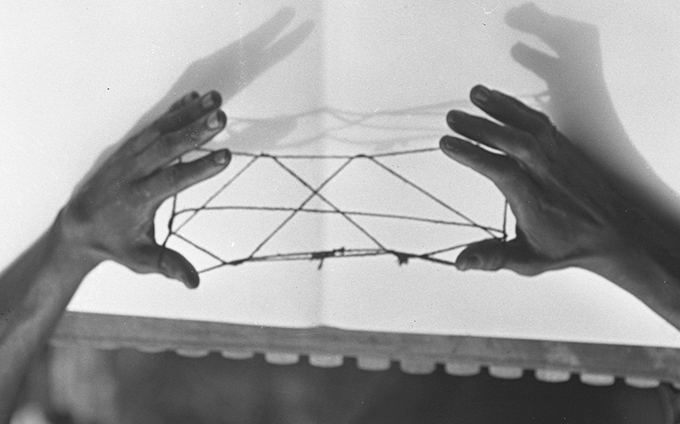

2. Basket spirits use to carry person

N. W. Thomas: Okba mwo ji ebu mwadu; Central Igbo: Nkata mmụọ ji ebu mmadụ

Philip Noble notes: This figure is also known in Congo, Sudan and Equatorial Guinea. In Nigeria the design represents a palanquin (sedan chair) for transporting a chief. In its most primitive form a palanquin consists of a basket suspended between two parallel poles. The inclusion of the word ‘spirits’ in the title may refer to an ancient custom, recorded by P. A. Talbot, in which a large palanquin borne on the shoulders of six men, was used to transport a ‘spirit’ during a funeral ceremony.

3. Big piece of yam

N. W. Thomas: Ibeji okotoko; Central Igbo: Nnukwu ibe ji

Philip Noble notes: Identical or closely related figures are known throughout Africa. Nigerian yams belong to the genus Dioscorea. Prior to cooking, yams are peeled and cut into cubes, which are represented by diamonds in the corresponding string figure.

(See video below.)

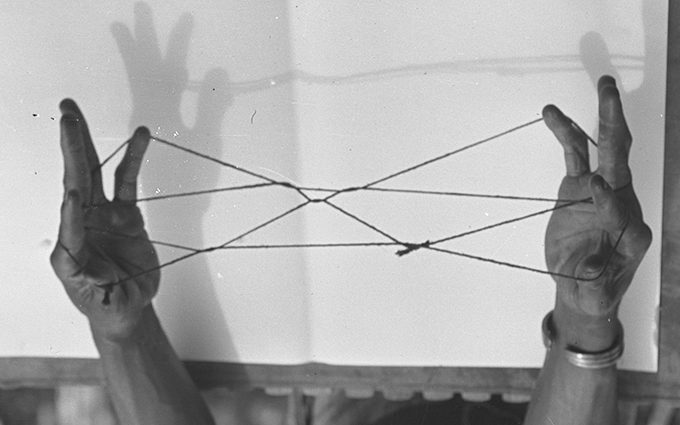

4. Child of monkey eats and tears its tail

N. W. Thomas: Nwenwelie ora odo; Central Igbo: Nwa enwe rie ọ dọkaa ọdụ

Philip Noble notes: The construction is similar to a figure called ‘A Pair of Scissors’, published by Kathleen Haddon and Hilda Treleaven in The Nigerian Field in 1936, and another called ‘Aeroplane’ recorded by George Cansdale in Ghana.

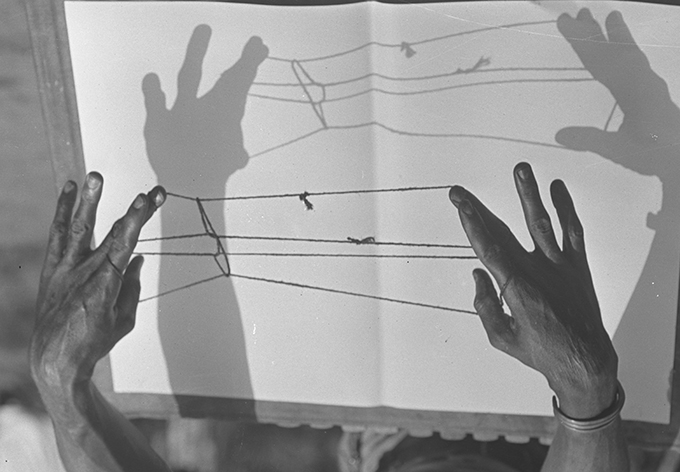

5. Corpse and cloth

N. W. Thomas: Ozu nakwa; Central Igbo: Ozu na akwa

6. Big belly of old woman

N. W. Thomas: Okulu agadin waiyi; Central Igbo: Nnukwu afọ agadi nwaanyị

Philip Noble notes: This figure is identical to No. 19 in George Cansdale’s collection, ‘Ghana String Figures’, published in The Nigerian Field in 1993, which has the name ‘When this animal went to fetch water, the sun came down’. In the Nigerian counterpart the loose hanging loop represents the sagging belly of an old woman.

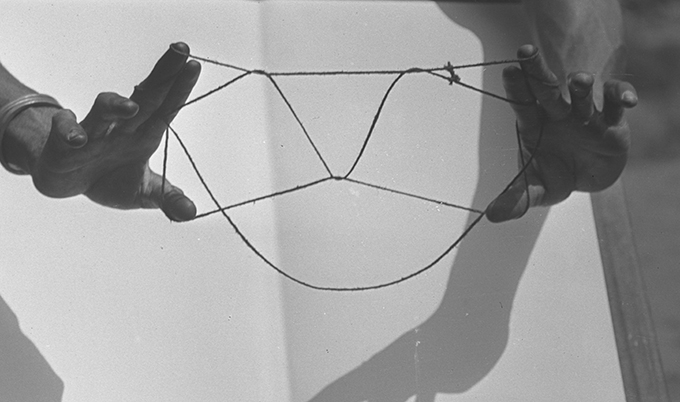

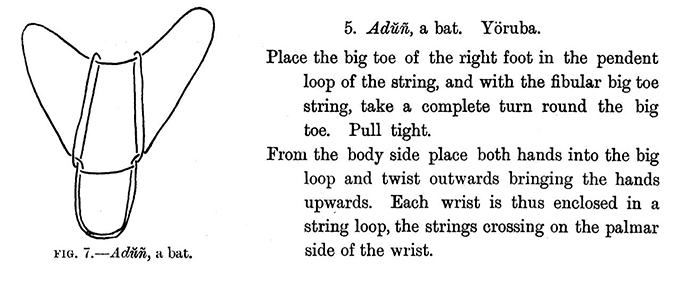

7. Bull with long horn

N. W. Thomas: Okefi mpi agi liga; Central Igbo: Okeehi ogologo mpi

Philip Noble notes: The design represents a bull’s triangular face and his two horns. This figure is the same as one called ‘Bat’ published by Kathleen Haddon and Hilda Treleaven in The Nigerian Field in 1936. It was also recorded by the geologist, John Parkinson, in Yoruba-speaking areas of Southern Nigeria and published in 1906, also named ‘a bat’.

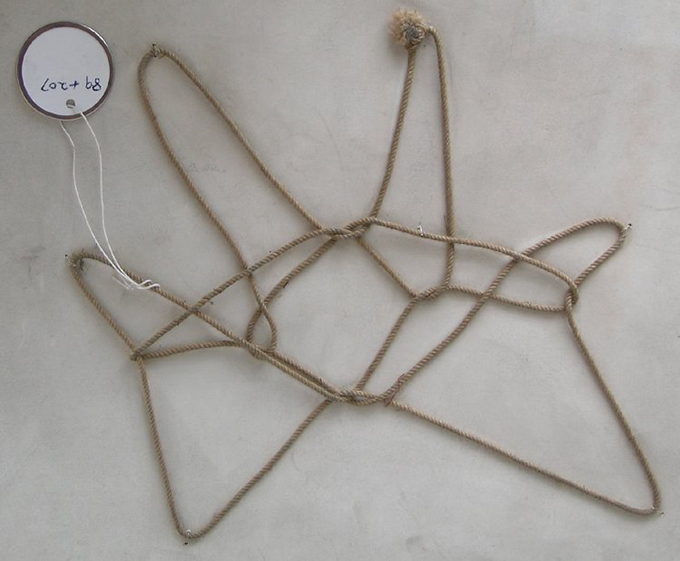

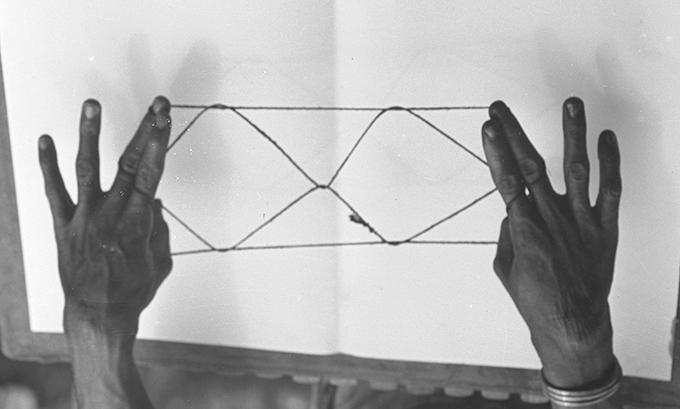

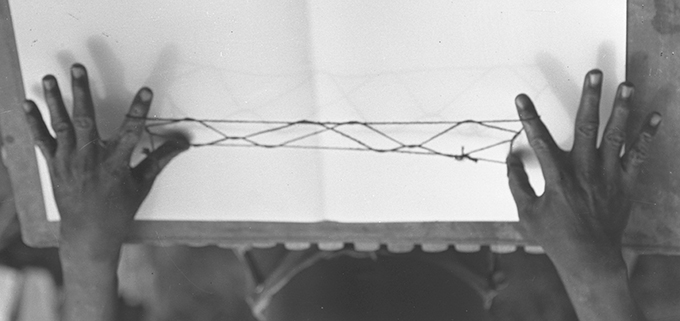

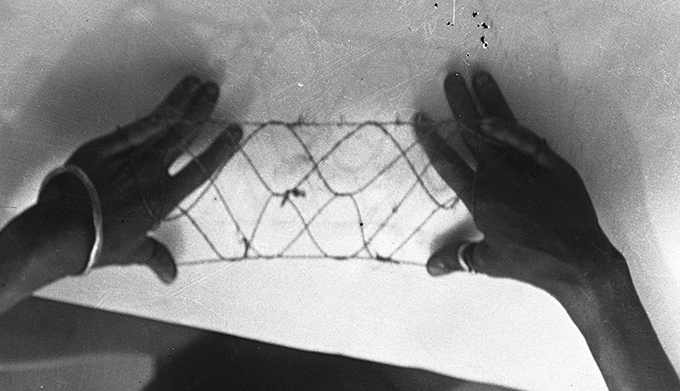

8. Net for load

N. W. Thomas: Ozo anele; Central Igbo: Ubu ibu

Philip Noble notes: This figure is widely distributed in Africa, where it often represents a ‘net’. It is the same as one called ‘A Bridge’ published by Kathleen Haddon and Hilda Treleaven in The Nigerian Field in 1936.

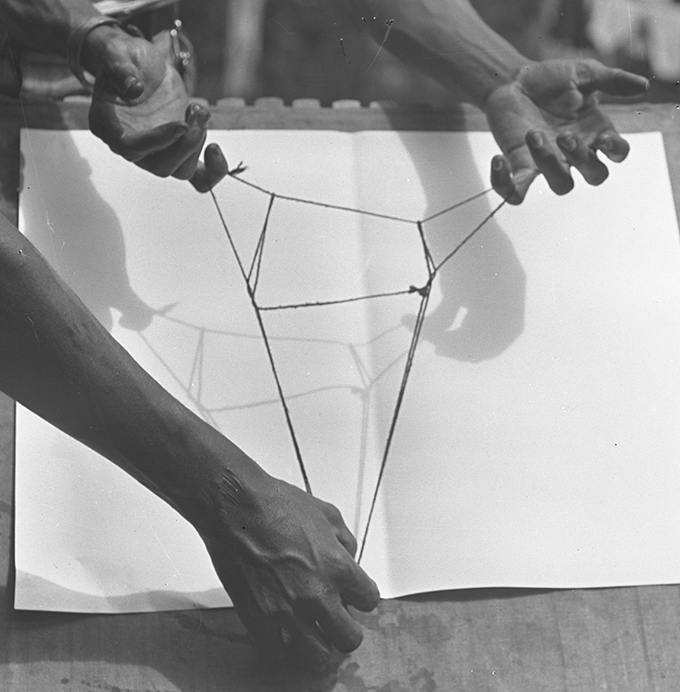

9. Mask for ‘juju’

N. W. Thomas: Oga; Central Igbo: Ihu mmanwụ ọgwụ

Philip Noble notes: The figure is widely distributed in Africa. It is the same as that published by John Parkinson in 1906 under the name ‘Moving Figure’.

10. Fowl’s anus

N. W. Thomas: Ubwadiye; Central Igbo: Ike ọkụkọ

11. Rope on back

N. W. Thomas: Bokulei; Central Igbo: Ụdọ n’azụ

Philip Noble notes: The central string represents a rope, presumably on the back of a person who is face down. The figure is identical to that published by Kathleen Haddon and Hilda Treleaven in The Nigerian Field in 1936 under the name ‘Dead Man Lying on a Bed’.

12. Trap

N. W. Thomas: Ibudu; Central Igbo: Ọnya

Philip Noble notes: This figure is the same as ‘Bongo Skin’ and ‘Buffalo Skin (Pegged Out)’ respectively published by George Cansdale in 1993 and C. L. T. Griffith in 1925, both recorded in Ghana/Gold Coast.

It would be interesting to find out if such string games are still played in Agukwu Nri and Ebenebe, and, if so, whether these figures and names are still known. We will try to investigate this in our fieldwork.

Written instructions for recreating each of the string figures photographed by Thomas can be found in Philip Noble’s full article ‘Some Nigerian String Figures’, which can be downloaded from the link below. (Please note that there are some discrepancies between the names of string figures used in this blog and those in Philip Noble’s article. I have used the captions of the photographs in Thomas’s albums as the most reliable guide, but, since some of the photographs share the same negative number, it is possible that Thomas got these muddled up himself!) Many thanks to Philip Noble and Mark Sherman for permission to draw upon and republish Philip’s article, to Philip for producing the excellent demonstration videos, and to Yvonne Mbanefo, Emeka Maduewesi and Ayodeji Ayimoro for their help with Igbo names for string games.