Northcote Thomas recorded hundreds of folksongs, stories and proverbs during his anthropological surveys in Nigeria and Sierra Leone at the beginning of the twentieth century. These were recorded through a sound horn, diaphragm and needle onto wax cylinders using a phonograph. This technology has long been obsolete and it is only now, through digitization, that we have been able to begin exploring the ‘sound heritage’ that has been locked away in these fragile cylinders. The British Library holds Thomas’s original recordings and, having undertaken the painstaking work of digitization, has made them available to the [Re:]Entanglements project to experiment with.

Even once they are digitized, Thomas’s sound recordings are not easy to work with – the recordings are often faint, the noise levels high. Just as challenging are the linguistic changes that have taken place over the past 100 years. In Nigeria, for example, Standard Igbo has replaced the local dialects that Thomas recorded in many areas. It has, however, been especially rewarding collaborating with local experts, who have been helping us to explore this rich archive and its contemporary affordances.

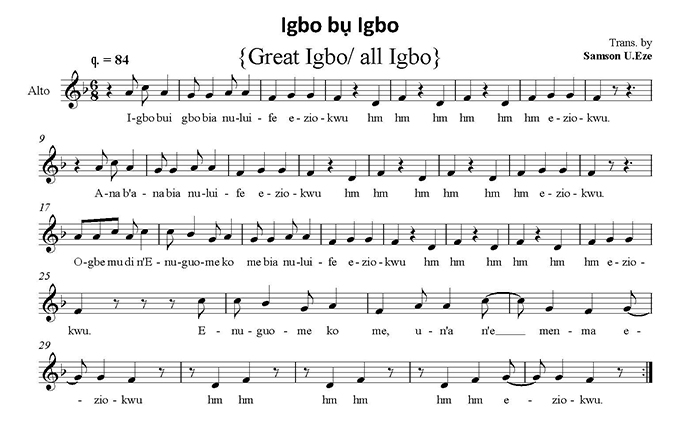

Samson Uchenna Eze, for instance, is a lecturer in the Department of Music at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. He has been working on a number of folksongs recorded by Thomas in Awka in 1910-11. In this guest blog, he describes the process of transcribing and re-recording three of these songs with local performers. Eze was even inspired to compose a contemporary choral piece based on one of Thomas’s recordings – NWT 417, Igbo bu Igbo – and has made his score available here. Eze’s account is interesting for many reasons, not least in highlighting the amount time and effort required to fully engage with these historical recordings. His closing reflections on the significance of Thomas’s recordings as well as the challenges of conducting research on them in contemporary Nigeria are profound.

I am Samson Uchenna Eze, a lecturer in the Department of Music, University of Nigeria, Nsukka, and an alumnus of the same institution. I hold a Diploma in Music Education, a BA in Music and MA in Music Performance. My participation in the transcription and re-recording of some of Northcote Thomas’s recordings was born out of a passion for music archaeology and ethnomusicology.

I was introduced to the [Re:]Entanglements project by Prof. Paul Basu during a workshop he organized at the University of Nigeria in 2018. Following the workshop, I presented a proposal to work on some Igbo folksongs recorded by Northcote Thomas in Awka, Southern Nigeria, in 1910-11.

Having selected three recordings, for which I could hear and understand most of the lyrics, I invited a group of indigenes of Awka to work on these tracks with me. They were Goodness Okwuchuckwu, Kosisochukwu Sandra Adigwe, Confidence Kosisochi Ndụdinanti, Agatha Oby Mba and Mmesoma Dilichukwu Emekwisia. Together we set about listening, transcribing, rehearsing and exploring the meanings of the songs. Due to the poor sound quality, I used audio editing software to amplify the voices and reduce noise on the historical recordings, making it possible for everyone to hear the playback well.

I spent time in Awka, enlisting the help of others in understanding the meaning of the lyrics and other details of the songs. At Ọkpụnọ Awka, I met two elderly men and an old woman. After listening to the songs they directed me to Ụmụdịọka where they believed the songs were recorded. When I got to Ụmụdịọka, I met three elderly men at Ụmụ Udeke Ndị Ichie Hall who confirmed that the voices have the intonation of the Ụmụdịọka people. They identified the songs as Egwu Ọnwa – ‘moonlight songs’; songs performed as part of communal music-making activities during the evening and accompanied by dancing. They explained that the word Odumodu, which features in one of the songs means ‘leopard’, and that ana bụ ana, which features in another, means ‘all communities’. These elders preferred to remain anonymous.

Meanwhile the five performers and I met several times to recreate and rehearse the songs. Each of the rehearsals was very fruitful because it helped us to understand these ancient recordings more. In June 2019, with the assistance of George Agbo, we video recorded performances of each of the tracks. We recorded each twice: firstly, with one or two voices as can be heard on the original recordings; secondly, as a rendition of mixed structural ensemble. The major difference when one compares the new recordings with Thomas’s originals is the sense of regular rhythm and tonality in the new work. Percussive instruments – an Udu (pot drum) and Ichaka (gourd shaker) – were added to make the music danceable.

Igbo bụ Igbo (Great Igbo)

Northcote Thomas Record No.417 (British Library: C51/2277), recorded in Awka on December 16, 1910.

Lyrics in Igbo

Igbo bụ Igbo bịa nụlụ ife eziokwu, hm eziokwu

Ana bụ ana bịa ifve eziokwu, hm eziokwu

Ogbe m dị n’Enugu Omekome bịa nụlụ ifve eziokwu, hm eziokwu

Enugu Omekome, unu ana-eme nma, eziokwu

Igbo bụ Igbo bịa nụlụ ifve eziokwu, hm eziokwu

Lyrics in English

Great Igbo (all Igbo), come and hear the truth

All lands, come and hear the truth

Enugu people, my great neighbours, come and hear the truth

Enugu people, you keep on doing good, the truth

Great Igbo (all Igbo), come and hear the truth

In this song the female singer repeats the phrase several times and improvises in the internal variation section, calling on neighbouring villages to come and hear the truth. The song begins on F pentatonic mode that maintains compound duple time. It is a song of admonition that calls on the Igbo-speaking peoples to stick to the truth. It is a moonlight song.

With the incursion of colonial power in the early twentieth century, the identity of the Igbo nation was lost, and the repercussions of this are felt to this day. This song issues a maternal call for all Igbo to return to our truthful ways. The message in this song inspired me to compose a short four-part vocal piece. I included a few additional words to support the call for sticking to the truth, but they remain minor features to the central theme. I thought of the message and its possible acceptance as a choral piece for social gatherings within Igboland and beyond. You are welcome to download the score (pdf). It can be performed by any choral group that wishes to do so.

Nwa mgbọtọ (The Young Woman)

Northcote Thomas Record No.405 (British Library: C51/2625), recorded in Awka on December 12, 1910.

Lyrics in Igbo

Nwa mgbọtọ eme m na m amarọ ihe

Nwa mgbọtọ eme m na m amarọ ihe

Nwa mgboto oo oo, Nwa mgboto oo oo

Nwa mgbọtọ eme m na m amarọ ihe

Nwa mgboto oo oo, Nwa mgboto oo oo

Nwa mgbọtọ eme m na m amarọ ihe

Nwa mgboto akpagbuo m na nganga

Nwa mgbọtọ eme m na m amarọ ihe

Nwa mgboto akpagbuo m na nganga

Nwa mgboto akpagbuo m na nganga

Nwa mgboto akpagbuo m na nganga

Nwa mgbọtọ eme m na m amarọ ihe

Nwa mgboto oo oo, Nwa mgboto oo oo

Iyooo Iyo, Iyooo Iyo

Iyooo Iyo, nwanyi ogbirigbi I ga taa gba kwa?

Iyooo Iyo, Iyooo Iyo

Lyrics in English

The young woman takes me for a fool

The young woman takes me for a fool

The young woman! The young woman!

The young woman takes me for a fool

The young woman! The young woman!

The young woman takes me for a fool

The young woman is showing off

The young woman takes me for a fool

The young woman is showing off

The young woman is showing off

The young woman is showing off

The young woman takes me for a fool

The young woman! The young woman!

(Wailing)

Woman, the good dancer, will you dance today?

(Wailing)

Nwa mgbọtọ (The Young Woman) is a mother’s lament. The melody emphasizes the B hexatonic minor mode in compound duple time. Most people who listened to this song wondered what the young woman did to the mother, which provoked such a lamentation. It is also sung by mother’s as a corrective against unseemly behaviour.

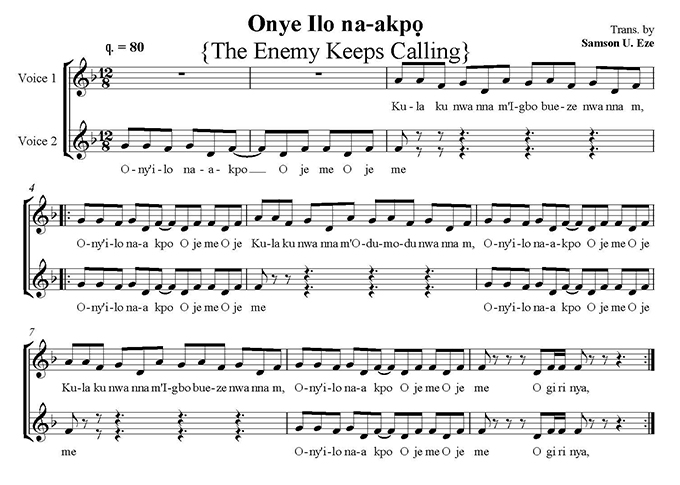

Onye Ilo na-akpọ (The Enemy Keeps Calling)

Northcote Thomas Record No.433 (British Library: C51/2671), recorded in Awka on January 25, 1911.

Lyrics in Igbo

Onye Ilo na-akpọ – Ojeme, Ojeme

K’lakụ nwa nna m, Igbo bụ Eze nwa nna m

Onye Ilo na-akpọ – Ojeme, Ojeme

K’lakụ nwa nna m, Odumodu nwa nna m

Onye Ilo na-akpọ – Ojeme, Ojeme

Lyrics in English

The enemy keeps calling

Clerk my brother, kingly Igbo my brother

The enemy keeps calling

Clerk my brother, Leopard my brother

The enemy keeps calling

The music is on D tetratonic mode in compound duple time; it is a repetitive call and response song. During the colonial era, people expressed their grievances through songs. The use of the word K’lakụ or ‘Clerk’ in the song indicates its connection with the colonial oppression of the Igbo people of Southeastern Nigeria. It is a song of praise as well as protest. The ‘Native Clerk’ was a controversial and ambiguous figure in the early twentieth century when Thomas recorded the song – they were local people, but also functionaries within colonial governance. It is a historical fact that Native Clerks took advantage of their positions and exploited the people to enrich themselves. We hear a statement of praise – ‘Clerk, my brother, kingly Igbo my brother, Clerk my brother, Leopard my brother’ – and a statement of protest – ‘The enemy keeps calling’. The people praised the Native Clerk, but referred to the ‘White Man’ as the enemy. In our discussions with elders, the dominant interpretation of the meaning of the song is that the British colonialists were the enemy that kept issuing instructions (the enemy that keeps calling). It would have been performed during moonlight dance.

Challenges and possibilities

The aesthetic value as well as the socio-cultural implications of Northcote Thomas’s recordings calls for further academic inquiry. Contemplating this remarkable sound archive has led me to ask many questions. Does such music still exist in Nigeria? How did people respond to such music at the time it was recorded and how might they respond to it now? How were these folksongs performed then? In what contexts are they performed now, if any? What about the influence of Westernization/globalization? What about the structural differences in tonality, harmony and rhythm when compared to contemporary interpretations of the folksongs?

The educational value of Thomas’s recordings is huge, especially as a body of indigenous instructional material amid calls for the decolonization of musical arts education in Nigeria. The records led me to consider how ordinary people responded to colonial oppression through song. The songs are an important historical source for understanding the experience of colonialism ‘from below’, and much more research of the kind we have begun here could be conducted in this respect.

One challenge I encountered in this research, however, is that many people here in Nigeria are seemingly either indifferent or ill-disposed towards these historical recordings. The task of finding local people to work with and reproduce the songs was not easy. Some people expressed that they were afraid of listening to the songs; some stated that they sounded frightening or esoteric; others said that it was the music of the dead. As a result they distanced themselves from any further discussion.

Furthermore, the present security challenge in Nigeria made people cautious when talking to me. In Nigeria today, a well-dressed young man moving from street to street, asking people for locations and begging them to listen to his music can be interpreted as a ‘419er’ – a fraudster. This is the situation of things; many persons ignored me because they thought I was on a mission to hoodwink them.

Despite all this, research for the [Re:]Entanglements project has spurred me to rethink my own Igbo culture and heritage, and to consider the important place of our indigenous music traditions in building national consciousness.

Thank you, Samson, for your inspiring and thought-provoking article and the brilliant research on which it was based! — Paul

All surviving recordings from N. W. Thomas’s four anthropological surveys are available at the project’s SoundCloud site. Do let us know if you are interested in translating, transcribing or recreating any of the tracks! We’d like to acknowledge the additional support of a small grant from British Library Sounds that has contributed to making this research possible.