Earlier generations of anthropologists have been criticised for their failure to properly account for the historical contingencies that frame the context of their fieldwork. In their writing they often represented the societies they studied as if they existed outside of time, evoking customs and cultural practices as if they had remained unchanged over the centuries. For anthropologists of Northcote Thomas’s generation, there was a further paradox insofar as they worked within a ‘salvage’ paradigm, documenting and collecting cultures that they believed were on the brink of extinction due to the incursion of European influence. Thomas acknowledged that colonial contact was destructive, but he did not question whether it was also inevitable.

Thomas arrived in Benin City at a time of tumultuous change, just twelve years after the sacking of the city during the Benin Punitive Expedition of 1897, in the aftermath of which Oba Ovonramwen was exiled to Calabar. Benin’s monarchy was eventually restored in 1914, when Ovonramwen’s son, Prince Aiguobasimwin, was installed as Oba Eweka II, but the interregnum between 1897 and 1914 was characterised by fierce political rivalry between different factions. This rivalry was played out in the context of the new political system introduced by the British colonial authorities, which included the appointment of a Native Council and so-called paramount chiefs. While purporting to respect traditional power structures, this system of ‘native administration’ weakened the indigenous system of government, creating new tensions and rivalries.

This was the fraught political context in which Thomas’s first tour as Government Anthropologist took place. Reading Thomas’s official report of this tour, his Anthropological Report on the Edo-Speaking Peoples of Nigeria, published in 1910, one is struck by the absence of any discussion of political structure. Indeed, given the primacy of sacred kingship in Edo, and the elaborate rituals that surround it, it is remarkable that Thomas should not devote a chapter to the subject in the report. It is important to remember, however, that Thomas’s reports were effectively British government publications, intended primarily for distribution to colonial officers. It is perhaps not surprising that they omitted such a controversial issue as kingship.

In fact, it appears that Thomas intended to write a more detailed account of Edo-speaking communities in Nigeria. An incomplete manuscript survives, which we will be piecing together as part of the [Re:]Entanglements project, that does include a chapter specifically dealing with kingship. This address such matters as the origins of kingship in Benin, the relationship between the Oba and the Uzama chiefs, rituals around succession and so on. The account does not, however, make mention of the destruction of the Oba’s Palace in 1897 or the dethroning of Ovonramwen, who was, after all, still living in exile at the time it was written.

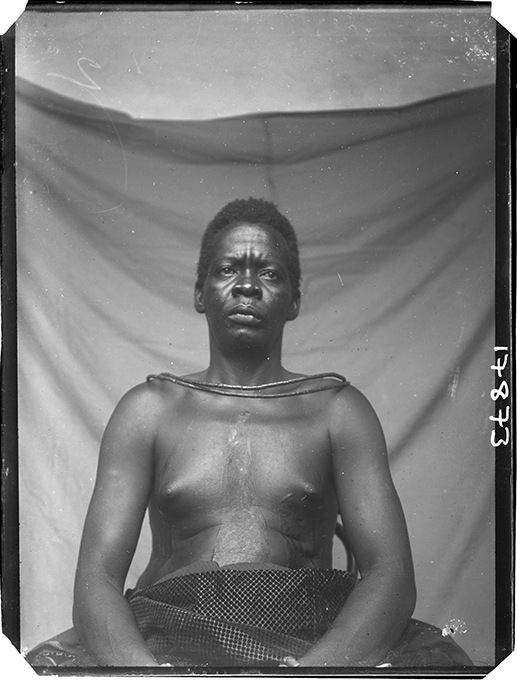

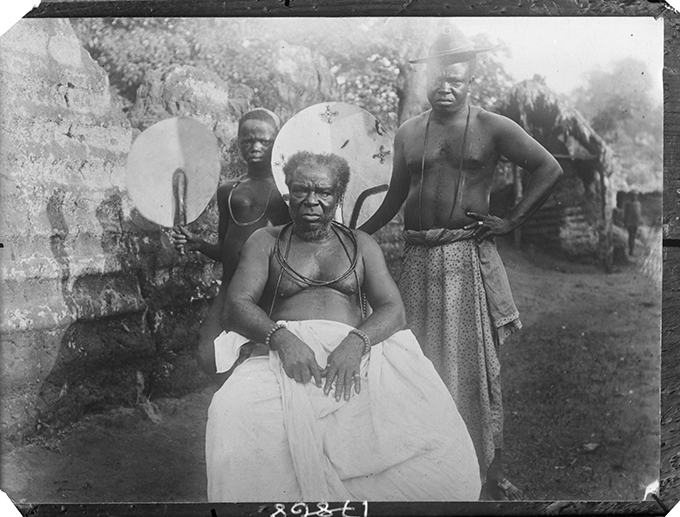

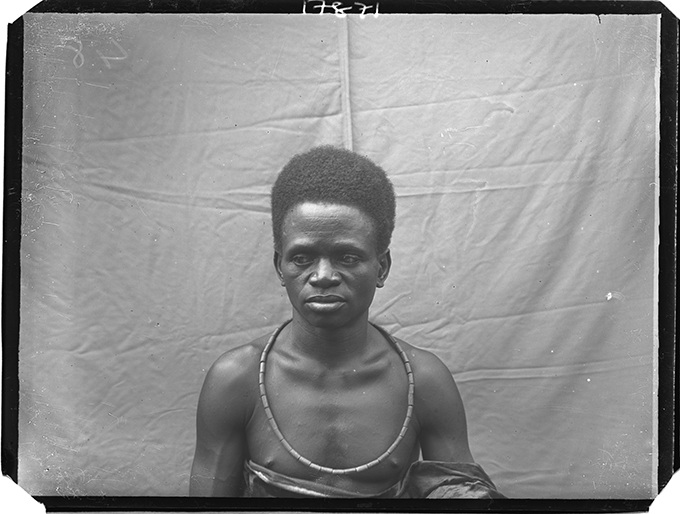

While Thomas was silent on colonial politics and contemporary power struggles among Benin’s elites, he was evidently granted audiences with and photographed many of the key figures involved. These included Chief Obaseki, Chief Ezomo, Chief Ero, Chief Osula and Chief Imaran. Chief Obaseki was close to the British administration and came to dominate the Native Council during the interregnum. He was ambitious and opposed the installation of Aiguobasimwin as Oba in 1914. Chief Ezomo and Chief Ero had been among the seven Uzama chiefs, and had played important roles within the pre-1897 Benin government. During the interregnum, these chiefs were all members of the Native Council. It is possible that Thomas’s are the only photographic representations of these important figures in the history of Benin. If Thomas himself was an unreliable witness to these events, his photographs, at least, constitute a unique historical record.

Further reading:

Igbafe, P. A. 1979. Benin under British Administration: The Impact of Colonial Rule on an African Kingdom, 1897-1938. Longman.