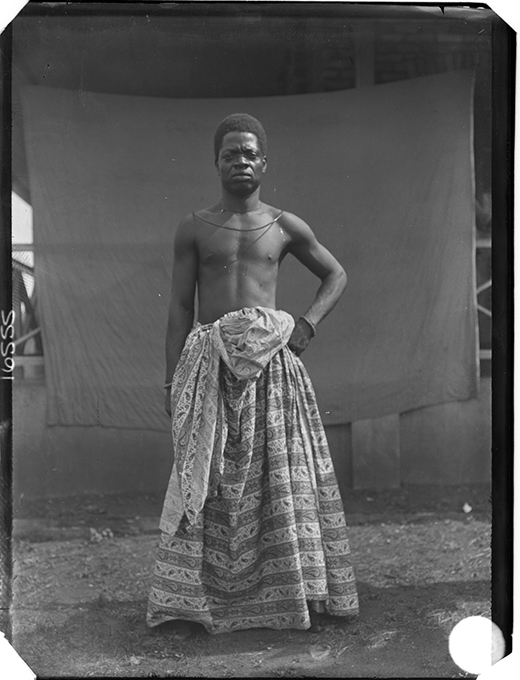

Further to our post on Northcote Thomas, Benin Kingship and the Interregnum, this photograph shows another controversial Benin chief who rose to power during Oba Ovonramwen’s exile. This is Chief Iyamu, a paramount chief appointed by the British colonial administration and given executive powers over a territory to the South East of Benin City at Urhonigbe.

In his history of Benin under British Administration, Philip Igbafe argues that such paramount chiefs ‘were ordinary chiefs and individuals who showed themselves to be useful agents of the British officers and had to be used to rule the extensive Benin Territories’. They were appointed ‘because they were loyal [to the British] and willing to serve, prepared to adapt to new conditions in order to retain influence, and could therefore be relied upon to do the bidding of the administrative officers’.

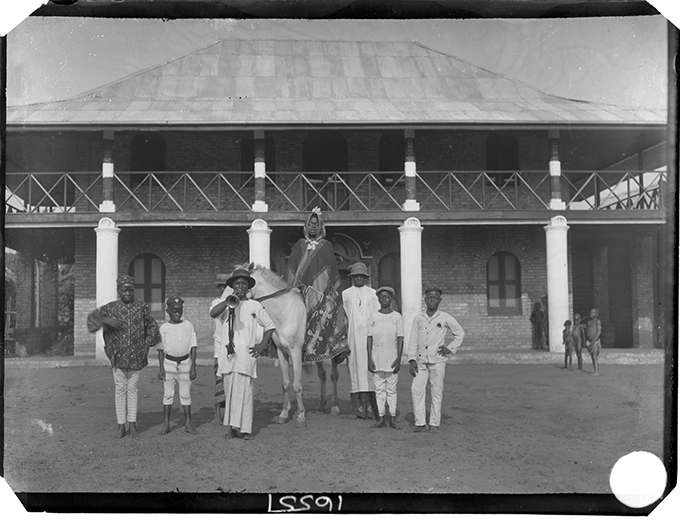

Chief Iyamu was photographed by N. W. Thomas seated on a white horse, surrounded by his retainers, and wearing a splendid gown. He is pictured in front of an imposing European-style house, known as Egedege N’okaro or ‘first storey building’. It was reputedly the first residential building constructed in Benin City with an upper storey. According to the Edo World website, construction of the house began in 1903-04 under the supervision of O. S. Crewe-Read, an Assistant District Commissioner, who was killed in 1906 at Owa by Ika resistance fighters. Although the circumstances are not clear, the house was given to Chief Iyamu, who completed its construction around 1905-06.

Although Thomas did not record the circumstances in which the photograph was made, one can surmise that Chief Iyamu had a hand in the mise en scène. Resplendent on his white horse, posed in the forecourt of his impressive Benin City residence, here is a carefully composed display of power, prestige and status.

At the same time, Chief Iyamu was a controversial figure. According to Igbafe, Iyamu was among those paramount chiefs who abused the power given them by the colonial administration, and it is likely that he would have been imprisoned for his misdemeanours had the British authorities not deemed it inexpedient to do so for political reasons. Despite the people of Urhonigbe rising up against Iyamu in 1912 and 1914, he was given the title Ine after restoration of the Obaship and crowning of Eweka II in 1914.

Egedege N’okaro is still standing, a well-known landmark on Erie Street in Benin City.

Many thanks to friends at the Nigeria Nostalgia Project for helping to piece together the story of this house.